The Astronaut Class of 1978, otherwise known as the “Thirty-Five New Guys,” was NASA’s first new group of astronauts since 1969. This class was notable for many reasons, including having the first African-American and first Asian-American astronauts. During Women’s History Month in March, NASA especially recognizes the class of 1978 as being the first to recruit women to its ranks: Sally Ride, Judith Resnik, Kathryn Sullivan, Anna Fisher, Margaret Rhea Seddon, and Shannon Lucid.

Of this original class, Sally Ride became the first American woman to fly in space in 1983 aboard STS-7; Judith Resnik earned the title of first Jewish-American in space on STS-41D; Kathryn Sullivan had the privilege of being the first American woman to walk in space on STS-41G; and Shannon Lucid became both the first mother to be selected as an astronaut candidate and the first American woman to fly to and work on a space station (Mir). Kathryn Sullivan and Sally Ride also earned the distinction of becoming the first two women to fly together on a mission when they flew on STS-41G in 1984.

Although they garnered much attention from the media and the public, Sullivan explained, “We didn’t want to become ‘the girl astronauts,’ distinct and separate from the guys. … All of us had been interested in places that were not highly female, and just wanted to succeed in the environment, at the tasks, and at all the other dimensions of the challenge.”

Even so, the six women sometimes faced humorous situations by being NASA “firsts.” Ride related one such story: “The engineers at NASA, in their infinite wisdom, decided that women astronauts would want makeup-so they designed a makeup kit. A makeup kit brought to you by NASA engineers. … You can just imagine the discussions amongst the predominantly male engineers about what should go in a makeup kit.”

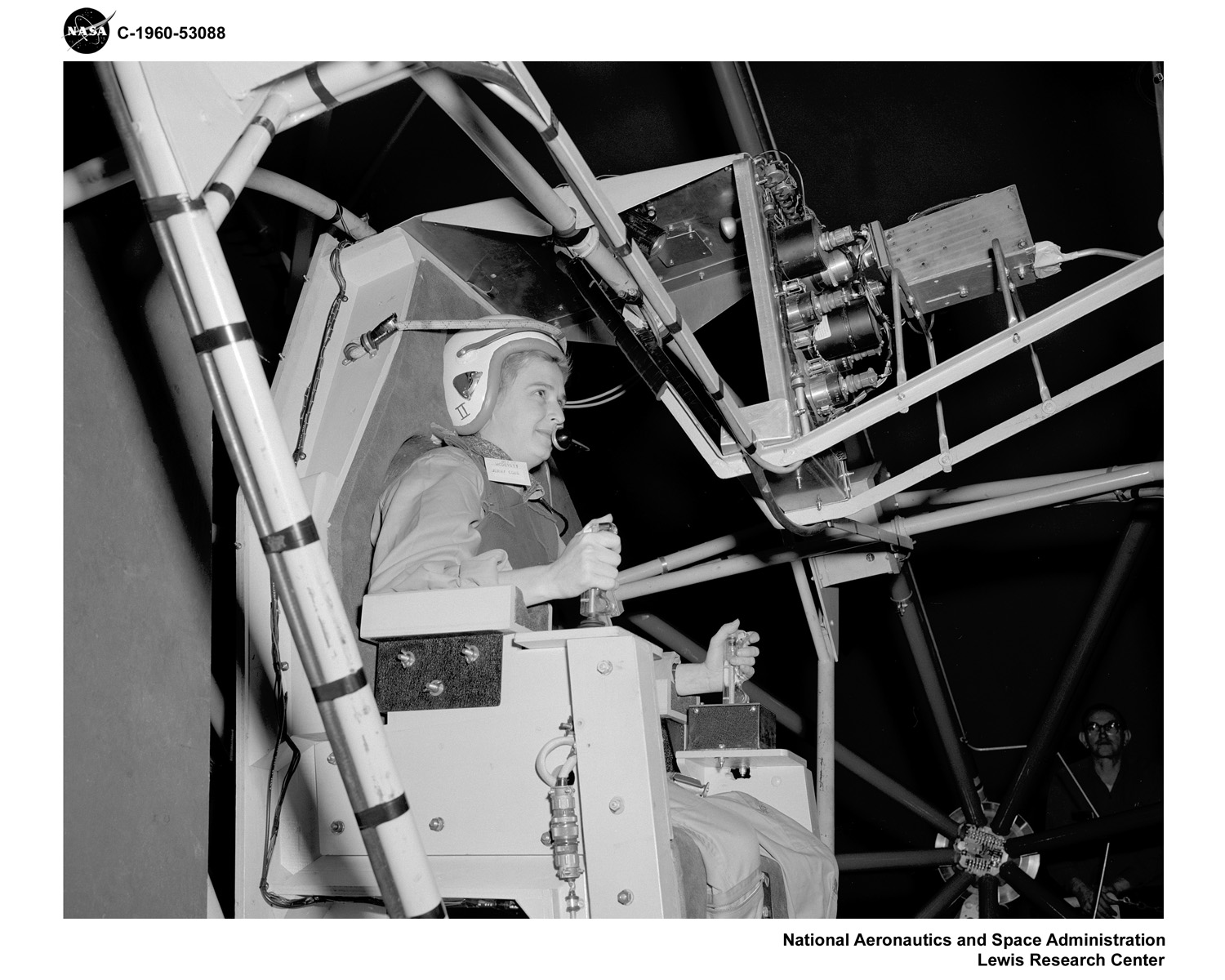

In total, NASA’s first women astronauts logged a combined total of 7,287 hours in space. However, the Class of 1978 was not, in fact, the original class of American women astronauts. Although never a NASA program, a group of women had been chosen and tested by William Randolph Lovelace, the man who originally helped to develop the tests for NASA’s Mercury Program in the early 1960s. Since the women were never officially recognized as an astronaut training group by NASA at the time, Lovelace conducted the tests in his private clinic. The first of these selected personally by Lovelace, Geraldyn (Jerrie) Cobb, coined the term “FLAT” – Fellow Lady Astronaut Trainees. After Cobb, 12 other women were selected: Wally Funk, Irene Leverton, Myrtle “K” Cagle, Janey Hart, Gene Nora Stumbough, Jerri Sloan, Rhea Hurrle, Sarah Gorelick, Bernice “B” Trimble Steadman, Jan Dietrich, Marion Dietrich, and Jean Hixson.

The women all had to be under 35 years of age and in good health, hold a second class medical certificate, have a bachelor’s degree, hold an FAA commercial pilot rating or better, and have over 2,000 hours of flying time. The early phases of testing were extremely rigorous, since no human being had yet flown in space. For example, to test how quickly the women could recover from vertigo, ice water was shot into their ears. They were also, among other things, put on a tilt table to test their circulation and subjected to a four-hour eye exam.

Even though the women passed the tests with flying colors, FLAT testing ended abruptly after the Navy refused to grant Lovelace and his women trainees further access to the testing facilities at the Naval School of Aviation Medicine in Pensacola, Florida, citing the lack of an official NASA request as the reason. The FLATs fought this termination of their unofficial program, and their plight eventually became the subject of a special Subcommittee of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics in July 1962. This subcommittee was created after Cobb met with Representative George Miller of California, chair of the House Space Committee. Miller, unlike many before him, offered to help, and called for the creation of the subcommittee to investigate. Representative Victor Anfuso of New York acted as chairman for the subcommittee, but due in part to negative testimony from Congressmen and NASA officials, including George Low, Scott Carpenter, and John Glenn, no action resulted from the hearings. Though this was expected, the defection of early female aviator Jackie Cochran was not. Cochran was intimately involved with Lovelace’s training program for women from the beginning since much of the funding for the FLAT medical testing came from Cochran and her husband. In fact, her husband was chairman of the Lovelace Foundation’s board of trustees. It remains somewhat unclear as to why she decided to speak out against the program during the subcommittee hearing; however, there is some evidence to suggest that Cochran was displeased both with the media attention given specifically to Cobb and with Lovelace for ignoring her requests to be one of the test candidates due to her age and prior health conditions. Regardless of the outcome, the hearing was a monumental moment, as it marked an investigation about sex discrimination two years before the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The FLATs were never granted the opportunity to fly in space. Until the Astronaut Class of 1978 was selected NASA insisted that all astronauts have military jet test pilot experience, thereby eliminating all women until that time. (The military test pilot requirement was originally established by President Eisenhower himself in December 1958.) Nevertheless, many of the FLATs have since been recognized throughout the years for helping to – eventually – pave the way for future women in America’s space program. Many years after having been shut out of the Mercury program, astronaut Eileen Collins invited the surviving women to her first launch in 1995. The FLATs have a special bond with Collins, who, with her 1995 flight, represented the fulfillment of their 30-year dream of seeing an American woman pilot astronaut.

As of this writing, there have been 71 female astronauts in the history of space exploration, hailing from all parts of the globe. Many have flown, and some still await their chance to fly. Women have not only flown on board as scientists and mission specialists, they have piloted and commanded America’s recently retired Space Shuttle fleet, as well. As Sally Ride once remarked at the beginning of the 21st century, “Now people don’t notice there are women going up on Space Shuttle flights. It’s happening all the time.” Women’s involvement as astronauts has continued to grow, as Susan Helms became the first woman aboard the International Space Station in 2001 and Peggy Whitson became its first female commander in 2007. Most recently, Sunita Williams commanded the Station during Expedition 33 in 2012. Both at NASA and internationally, women continue to reach for the stars, both literally and figuratively.

Michelle K. Dailey

Spring 2013 Intern

NASA History Office