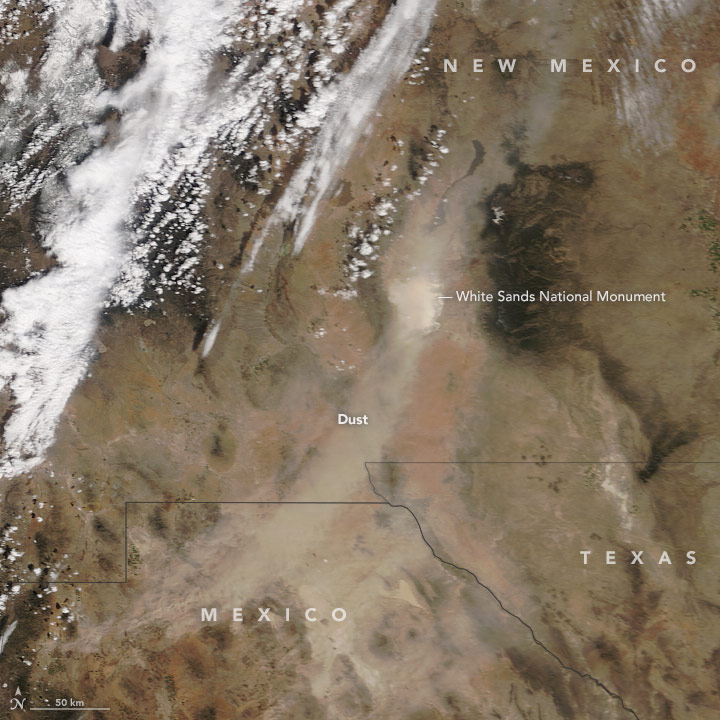

Valley fever is a dangerous threat to human health – and cases are on the rise in the arid southwestern United States, as wind from increasing dust storms can transport the fungal spores that cause the disease. Valley fever is caused by the Coccidioides fungus, which grows in dirt and fields and can cause fever, rash and coughing. Using NASA research and satellite data, the World Meteorological Organization is refining its Sand and Dust Storm Warning Advisory and Assessment System to help forecast where dust risk is greatest.

George Mason University’s Daniel Tong, one of the first scientists to discover the link between dust storms and Valley fever, leads a NASA-funded team to track the airborne spread of Valley fever across the United States for the first time.

There are about 15 thousand cases of Valley fever in the U.S. each year, and approximately 200 deaths, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Funded by NASA’s Earth Science Division, Tong’s team is helping track disease risk for epidemiologists, health care providers and public health decision makers.

“Our paper was the first one to reveal the positive relationship between dust storms and Valley fever,” said Tong. “So now we’re asking the question: How can we detect that dust in the air?”

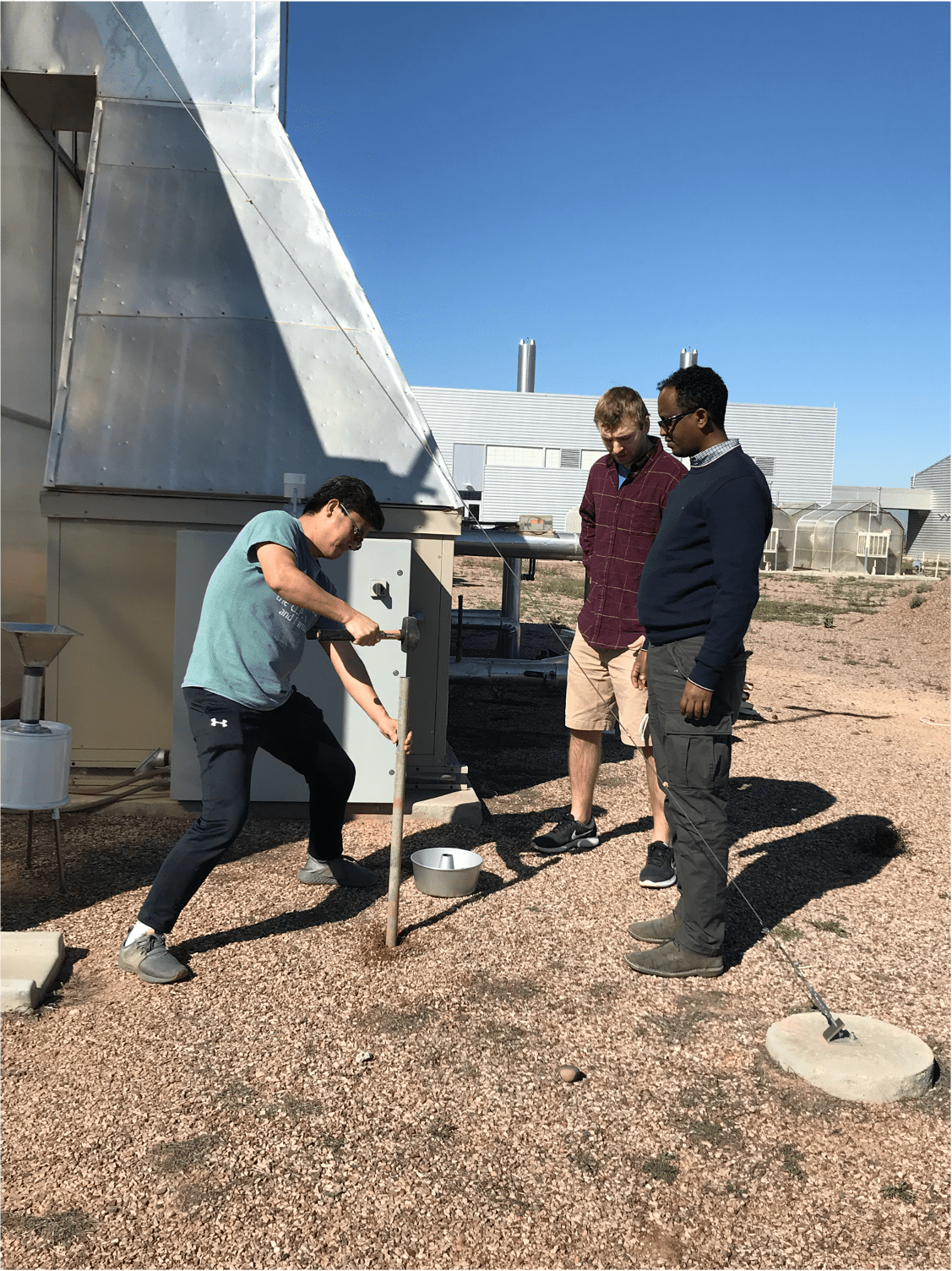

Tong and his team are combining NASA satellite data and high-end computer modeling with homemade dust catchers made of pans for baking cakes and marbles. Previously, on-site dust sampling was only available through expensive monitors, such as the ones used by the CDC. When they needed more sensors to cover exposure across a wide area, the team realized they could develop their own methods to capture the airborne dirt for a fraction of the cost.

One such method involves filling a store-bought baking pan – the kind used to bake a homemade birthday cake – with marbles. As wind passes over the uneven surface of the marbles, the interrupted flow causes the air to release the dust and spores it’s carrying. As the sediment falls through the layers of marbles to the bottom of the pan, it’s protected from being picked up by wind again, stored safely until the scientists come to collect several weeks’ worth of samples at a time.

The dust samples are sent to George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, with research support from George Mason University’s Institute for a Sustainable Earth. It is one of the few institutes in the country that can conduct DNA sequencing to identify the Coccidioides fungus in dust.

While the team gathers data on the ground, NASA satellites are hard at work getting the view from above. Tong’s team uses data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments aboard the NASA satellites Terra and Aqua. These data show likely habitats for this fungus because they monitor vegetation and soil moisture, revealing where conditions are ripe for fungal growth and spread of arid dust.

Currently the team is using that information on local plant growth as a measure to identify likely dust source areas. They’re working to shed more light onto the physical and biological processes for the fungus’s spread, which Tong says is important information for scientists and health officials to have. But tracking dust storms’ movement through air is easier with the help of NASA’s Earth observing instruments – like MODIS – which can also detect the light reflected from the tiny particles as they’re swept across the country. These true color dust observations from MODIS even helped to “train” models developed by the team to assess how the frequency of dust storms is changing.

“We have a satellite-trained algorithm developed with support from NASA to look at the long-term data of dust storms,” Tong said. “We were surprised to see dust storms in the American southwest increasing 10 times faster than the global level over the last few decades, causing increasing risk to local communities.”

Through the 1930s, dust storms in the Western U.S. famously destroyed farms and forced families to abandon homes. “Climate change is bringing that threat back,” warned Tong. “Global climate models predict the west and southwest will become drier and drier, meaning we could have dust bowls – plural.”

Tong says that with more dust storms there will be more instances of Valley fever. For reasons that are not well understood, some people are more susceptible to the effects of Valley fever than others. Only 40 percent of people infected have symptoms, and 8 percent of those go to the hospital. “There’s no vaccine – the fungus lives with you for the rest of your life,” said Tong. “Those infected are paying about US $50,000 per hospital visit, and a quarter of those people have to go ten times or more.”

Tong’s team collaborates with the federal CDC as well as state and local public health officials in New Mexico, California and Arizona. As the threat of Valley fever rises, local health officials hope Tong’s research will continue to uncover ways to track its dangerous spread.

“Now that we’re beginning to understand the risk to public health, the scientific community is really coming together,” said Tong. “They’re very curious, going out of their own way to help. I feel very lucky to have this support.”

The team is working with local agencies to place the sensors in areas with frequent dust storms to see where Valley fever might be affecting the most people. Local health agencies like the Pinal County Public Health Department in Arizona and community physicians are already incorporating these data to inform health and safety measures like increased testing and public education.

Next, the National Weather Service (NWS) and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) are working to incorporate this research to improve dust forecasting for everything from air quality to visibility for transportation. “We aim to bring longevity to this project,” Tong said, “so people can continue using this research to protect public health in the future.

For communities in the southwest, that means informing public health decisions in the face of increasing dust storms in the future.

By Lia Poteet, NASA Earth Science Division – Applied Sciences