Humans “heart” Earth. The cardiovascular system that includes both the heart and blood vessels has evolved to operate in Earth’s gravity while standing, sitting or lying down. Daily physical activity while working or exercising against gravity keeps everything flowing smoothly.

As soon as astronauts arrive in microgravity, and while they remain on the International Space Station, blood and other body fluids are pushed “upward” from the legs and abdomen toward the heart and head. This fluid shift causes a decrease in the amount of blood and fluid in the heart and blood vessels even while astronauts experience swelling in the face and head.

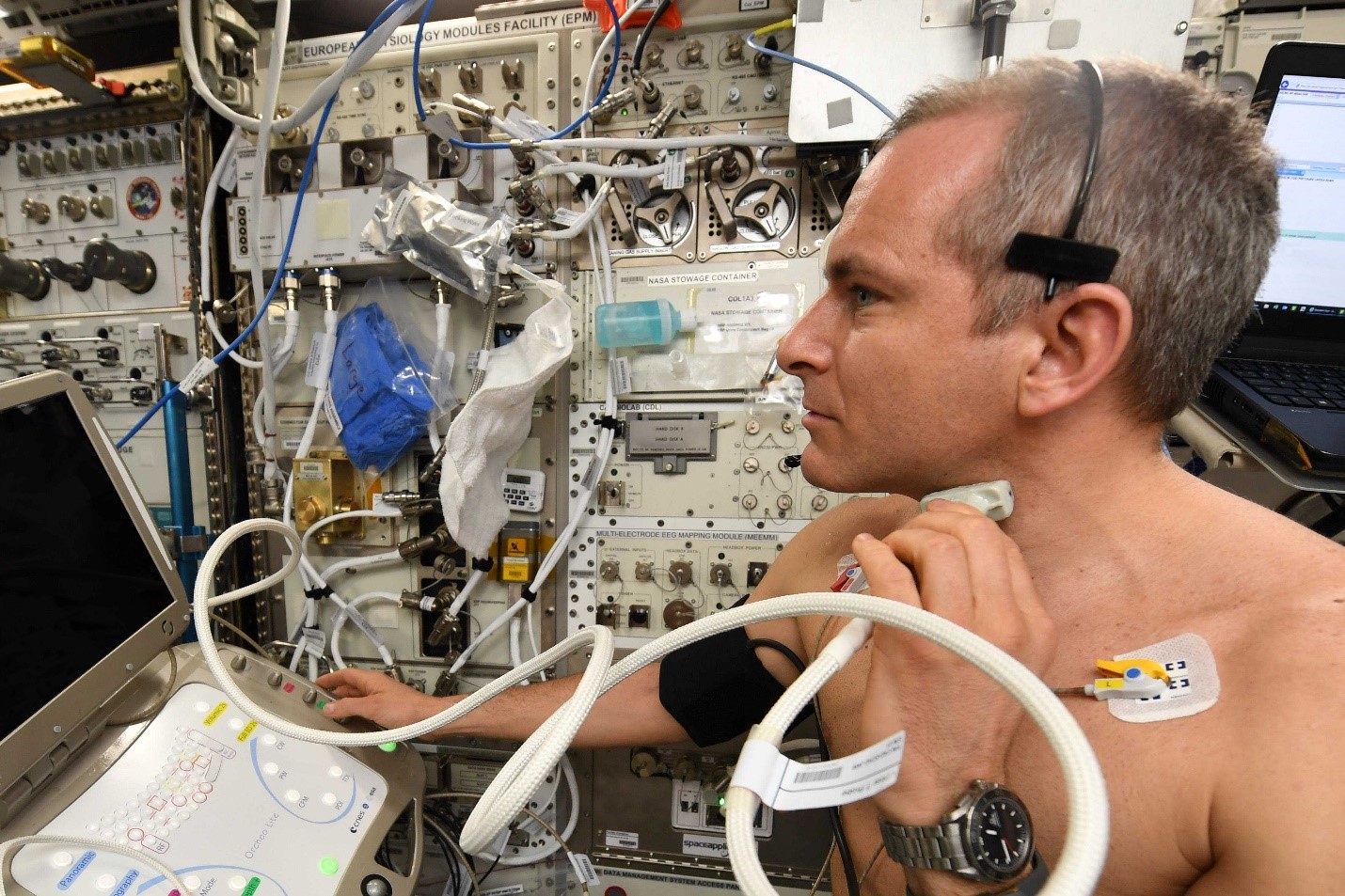

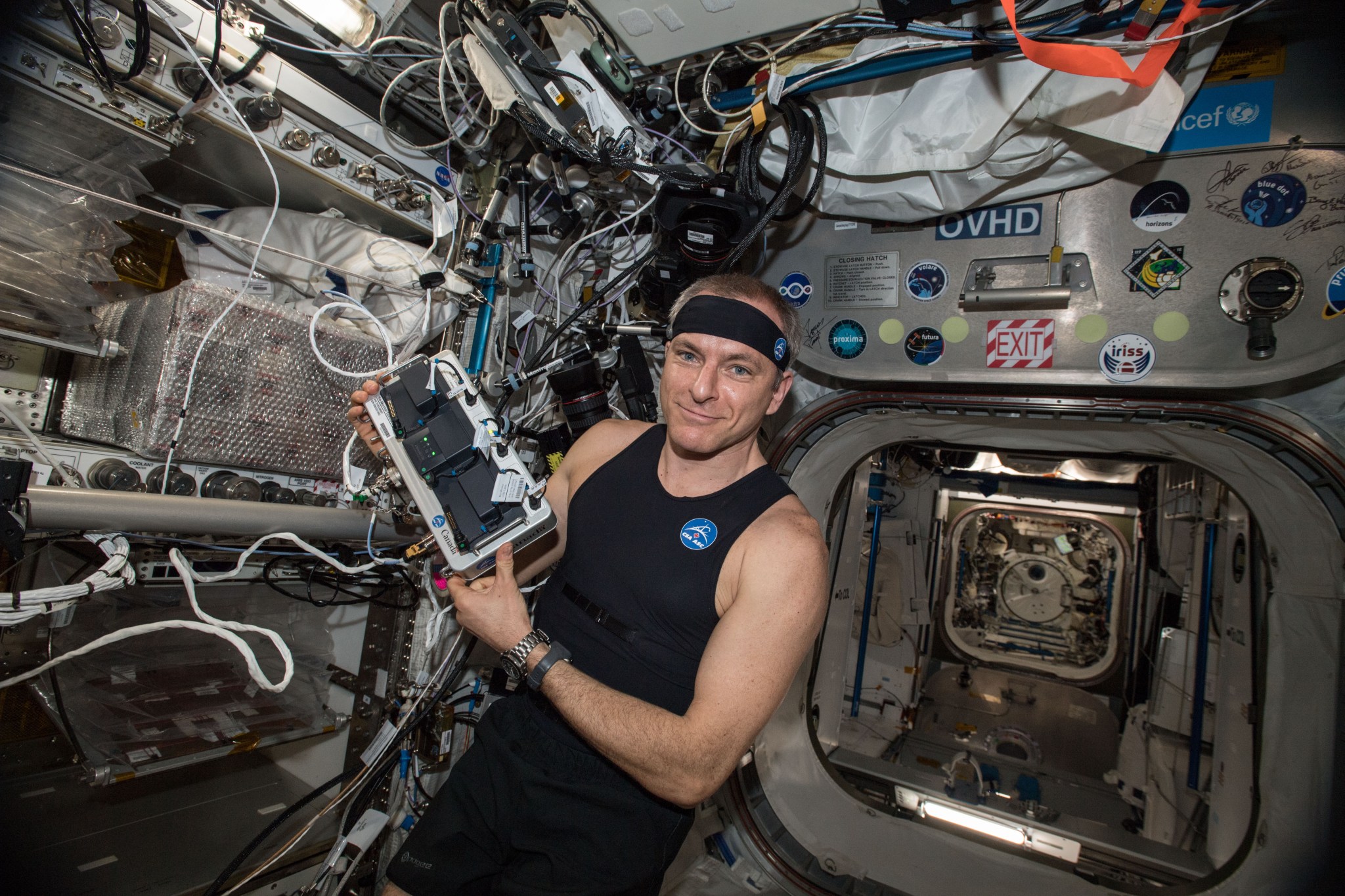

Because spending time in space affects the human heart and circulatory system, quite a bit of research conducted aboard the space station looks at these effects in both the short- and long-term. Much of this research aims to develop and test countermeasures to cardiovascular changes. What we learn has important applications on the ground as well, in part because many of the changes seen in space resemble those caused by aging on Earth.

Fluid shifts experienced by astronauts during extended microgravity missions on the space station affect not only the cardiovascular system but also the brain, eyes and other neurological functions. The apparent increase in fluid within the skull is thought to increase brain pressure, which can cause hearing loss, brain edema and deformation of the eye known as Spaceflight Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome (SANS). In microgravity the heart changes it shape from an oval (like a water-filled balloon) to a round ball (an air filled balloon), and space causes atrophy of muscles that on Earth work to constrict the blood vessels, so they cannot control blood flow as well.

On return to Earth, gravity once again “pulls” the blood and fluids into the abdomen and legs. The loss of blood volume, combined with atrophy of the heart and blood vessels that can occur in space, reduces the ability to regulate a drop in blood pressure that happens when we stand on Earth. Some astronauts experience orthostatic intolerance — difficulty or inability to stand as a result of light headedness and/or fainting after return to Earth.

Exercise in space is an efficient way to maintain most types of cardiovascular fitness. Equipment is available on the space station both for resistive exercises using the Advanced Resistive Exercise Device (ARED) and aerobic exercises using a treadmill or stationary bike. In addition, astronauts can wear special trousers that use pressure differences to pull blood back into the abdomen and legs.

Important research is being done on the space station to learn more about SANS and to develop and test countermeasures to the many possible different cardiovascular changes.

This space station research has important applications on Earth as well, in part because many of the changes seen in space resemble those caused by aging or illnesses — cardiovascular dysfunction due to inflammation, lack of exercise, possible intracranial hypertension, orthostatic intolerance, and hormonal and metabolic changes. Scientists are examining the underlying cellular mechanisms behind many cardiovascular system changes not only in astronauts, but also by using model organisms, cell cultures, organs on a chip and stem cells.

Whether they go to space or not, all humans can “heart” cardiovascular research on the station.