On Sept. 17, 1962, NASA announced the selection of its second group of astronauts. Chosen from 253 applicants, the Next Nine as the group called themselves, consisted of four Air Force, three Navy, and for the first time two civilian pilots. NASA selected them primarily to fly the two-seat Gemini spacecraft designed to test techniques for the Apollo Moon landing program. Tragically, one of their members died in a plane crash while training for his first mission, and another died in the Apollo 1 fire. The seven remaining members of the group flew important missions in the Apollo program, with six traveling to the Moon and three walking on its surface. In addition, one flew a long-duration mission aboard Skylab, another flew on the first joint flight with the Soviet Union, and a third flew twice on the space shuttle, including its inaugural voyage.

The Group 2 astronauts pose following their introduction during the

Sept. 17, 1962 press conference – front row, Charles “Pete” Conrad,

left, Frank Borman, Neil A. Armstrong, and John W. Young; back row,

Elliot M. See, left, James A. McDivitt, James A. Lovell, Edward

H. White, and Thomas P. Stafford.

On April 18, 1962, NASA launched a widely-advertised campaign for its Flight Crew Training Program to select five to 10 new astronauts. The space agency needed more astronauts than the seven selected in April 1959 for the Mercury program to fill out crews to test and operate the new two-seat Gemini spacecraft. The astronauts flying in the Gemini program would demonstrate the various techniques needed to achieve President John F. Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon. From the 253 applications received by the June 1 deadline (one arrived a week late, but managers chose to accept it anyway), NASA whittled the field down to 32 finalists who underwent intensive medical examinations at Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio. During this phase, physicians disqualified one candidate for exceeding the height requirement. In July and August, the 31 finalists appeared before the selection board for further tests and interviews by Coordinator of Astronaut Activities Donald K. “Deke” Slayton and the other members of the board. On Sept. 14, Slayton telephoned the nine newly-selected astronauts with the good news. Robert R. Gilruth, director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, now NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, introduced the nine new astronauts during a press conference held at the University of Houston’s Cullen Auditorium on Sept. 17. This second group of NASA astronauts, known as the New Nine or the Next Nine to differentiate them from the Original Seven Mercury astronauts, included Neil A. Armstrong (civilian), Frank Borman (U.S. Air Force), Charles “Pete” Conrad (U.S. Navy), James A. Lovell (U.S. Navy), James A. McDivitt (U.S. Air Force), Elliot M. See (civilian), Thomas P. Stafford (U.S. Air Force), Edward H. White (U.S. Air Force), and John W. Young (U.S. Navy).

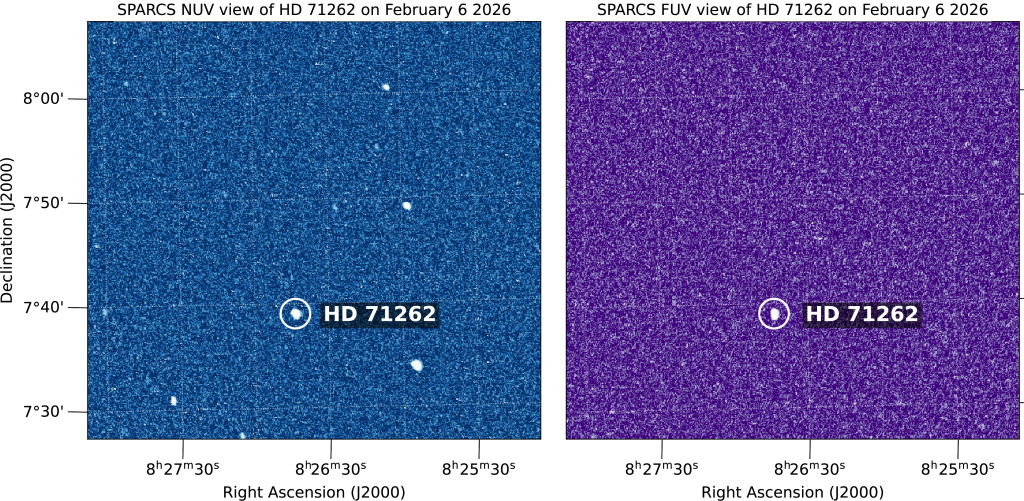

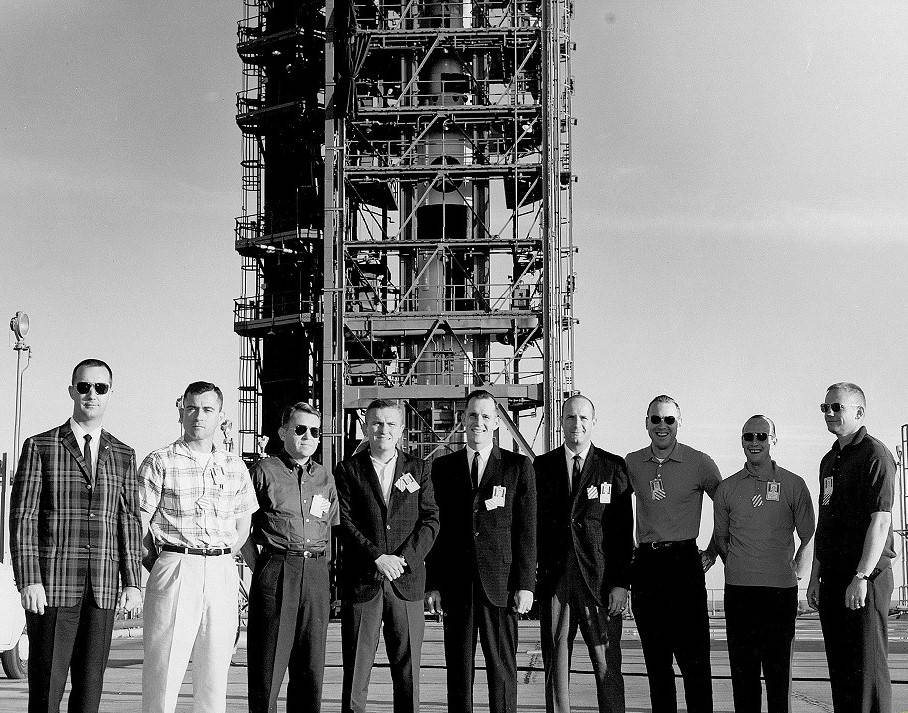

Left: The nine Group 2 astronauts pose in front of a Titan II rocket at Cape Canaveral – James A. McDivitt,

left, John W. Young, Elliot M. See, Frank Borman, Edward H. White, Thomas P. Stafford, James A. Lovell,

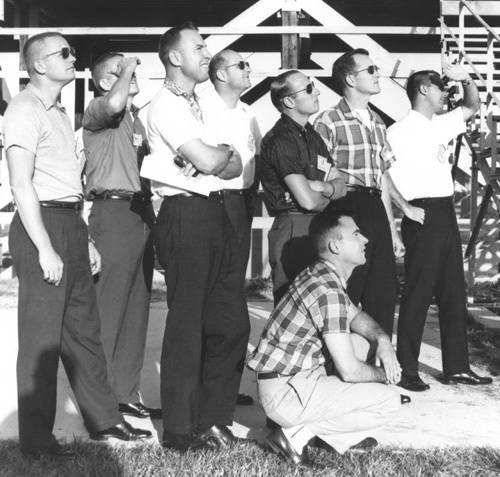

Charles “Pete” Conrad, and Neil A. Armstrong. Middle: Eight of the nine Group 2 astronauts watch the

launch of Mercury-Atlas 8 at Cape Canaveral – Armstrong, left, Borman, Lovell, Stafford, Conrad,

Young (kneeling), White, and McDivitt. Right: The Next Nine pose in front of an Apollo Command

Module mockup at the North American plant in Downey, California.

During their first few months as astronauts, the nine visited various NASA centers and contractor facilities to become familiar with the space program they volunteered for. One of the group’s first activities included a tour of facilities at Cape Canaveral in Florida in October. While there, they witnessed the successful launch of astronaut Walter M. Schirra aboard his Sigma 7 capsule on the six-orbit Mercury-Atlas-8 mission. In January 1963, they visited Meteor Crater in Arizona with geologist Eugene M. Shoemaker. Each astronaut received a technical assignment, to become an expert in specific aspects of spaceflight and pass their knowledge on to the rest of the group, and to help in the design of spacecraft, rockets, spacesuits, control systems, and simulators.

Photo of the Group 1 (front row) and Group 2 (back row) astronauts in February 1963.

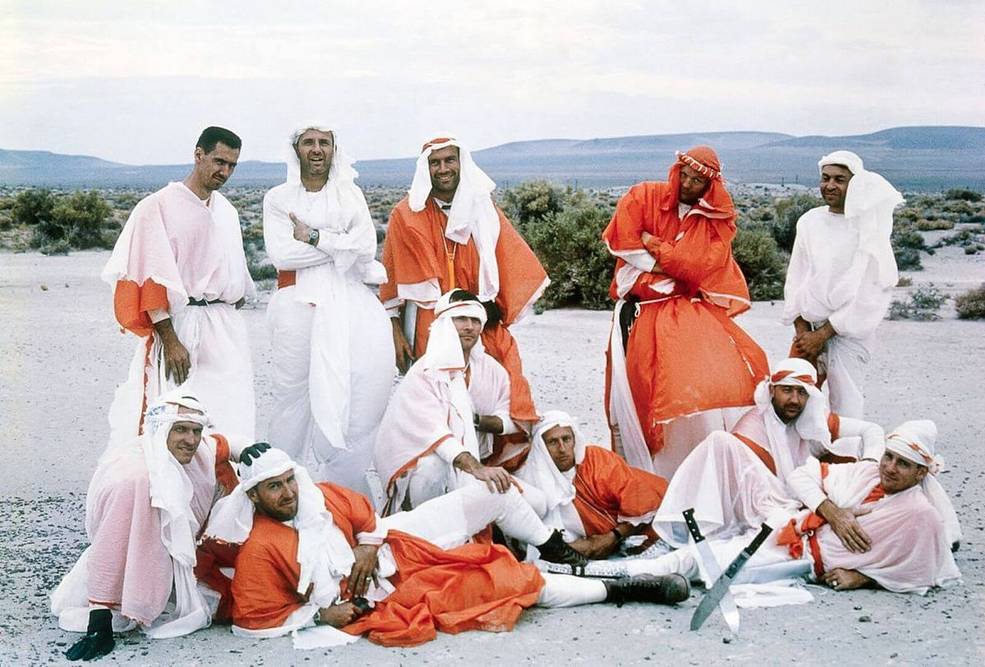

Left: Group 1 and 2 astronauts during survival training in Panama. Middle: The Next Nine during desert

survival training in Nevada. Right: In the new auditorium of the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC), now

NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, the introduction of the Gemini 3 crews – the backup crew of

Walter M. Schirra, left, and Thomas P. Stafford, MSC Director Robert R. Gilruth, the prime crew of

Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom and John W. Young, and Director of Flight

Crew Operations Donald K. “Deke” Slayton.

By June 1963, the New Nine had integrated with the Mercury Seven to form a 16-man astronaut corps. The group completed a week-long jungle-survival training at the Caribbean Air Command Tropic Survival School at Albrook Air Force Base in the Panama Canal Zone. The following month, they endured centrifuge training in Johnsville, Pennsylvania, followed by desert survival training in Nevada in August. In September, they underwent water-survival training at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Florida, and in November, they took helicopter flying lessons. Slayton could select crews for upcoming Gemini missions from this cadre of astronauts. He initially paired Mercury astronaut Alan B. Shepard with Stafford for Gemini 3, the first crewed flight of the new two-seat spacecraft, with Mercury veteran Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom and Borman as their backups. When Shepard’s medical condition grounded him, Slayton replaced the prime crew with Grissom and Young, with Schirra and Stafford as their backups. On April 13, 1964, during one of the first public events in the MSC auditorium at the new Clear Lake site, Gilruth and Slayton introduced the Gemini 3 crews to the press.

Group 2 astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, left, Frank Borman, and Charles “Pete” Conrad.

The one late application to the second group of astronauts belonged to Armstrong. Had managers not accepted it, one can speculate who would wear the mantle of first man on the Moon. Armstrong’s first technical assignment involved monitoring the development of mission simulators. For his first spaceflight assignment, Slayton selected him as the backup command pilot for the Gemini V mission, a planned eight-day endurance flight. He then rotated to prime command pilot for Gemini VIII. The flight completed the first docking in space, and Armstrong showed his mettle when an errant thruster forced an emergency return. He next served as backup command pilot for Gemini XI and as backup commander for Apollo 8, the first Moon orbital mission. As prime commander on Apollo 11, Armstrong took humanity’s first steps on the Moon. Slayton assigned Borman to monitor modifications to human-rate the Titan II missile. For Borman’s first crew assignment, Slayton named him as the backup command pilot for Gemini IV, from which he rotated to prime command pilot for the 14-day Gemini VII mission. After the January 1967 Apollo fire, Borman served on the team that investigated the cause of the accident and helped to oversee the redesign the Apollo spacecraft. His next crew assignment saw Borman as commander of an Apollo mission that became Apollo 8, the first crewed flight around the Moon. Conrad, who just missed out on selection for the Mercury group, served as pilot for the eight-day Gemini V mission, then as backup command pilot to Armstrong on Gemini VIII, before serving as command pilot of Gemini XI. In the Apollo program, Conrad served as backup commander on Apollo 9 before rotating to command Apollo 12, the second lunar landing, becoming the third person to walk on the Moon. For his fourth and final flight, Conrad commanded the first mission aboard Skylab, repairing the troubled space station during a then record-breaking 28-day flight.

Group 2 astronauts James A. Lovell, left, James A. McDivitt, and Elliot M. See.

Lovell, who like Conrad also just missed selection as a Mercury astronaut, first served as backup pilot on Gemini IV, then as pilot for the 14-day Gemini VII flight. In the crew shuffling that took place after the deaths of the Gemini IX prime crew, Lovell served as the backup command pilot for that flight and then as command pilot for the final mission of the program, Gemini XII. From his first Apollo assignment as backup Command Module Pilot for Apollo 8, he moved up to the prime position when the original astronaut was sidelined with a medical issue. He next served as Armstrong’s backup as commander of Apollo 11 and then made his fourth and final flight as commander of the ill-fated Apollo 13. McDivitt’s first assignment involved the development of spacecraft guidance and control systems, then his first crew assignment as command pilot for Gemini IV, the first rookie to command an American space mission. He temporarily served as the backup command pilot for Apollo 1, then as commander for Apollo 9, the first crewed test of the Lunar Module. McDivitt went on to serve as manager of the Apollo program office. Slayton assigned See to monitor the development of spacecraft electrical systems before assigning him as backup pilot for Gemini V. From that position, See rotated to the command pilot position for Gemini IX, but he and his pilot died in a plane crash on Feb. 28, 1966, just three months before their scheduled spaceflight.

Group 2 astronauts Thomas P. Stafford, left, Edward H. White, and John W. Young.

As noted above, Slayton initially assigned Stafford as pilot for Gemini 3, but after Shepard’s medical disqualification, he moved him to the backup crew. Following that assignment, Stafford served as pilot for Gemini VI, during which he and Schirra conducted the first rendezvous in space with Gemini VII. Next assigned as back up command pilot on Gemini IX, Stafford moved up to the prime position following the death of the prime crew, flying two missions just six months apart. For Apollo, he first served as the backup commander for Apollo 7, then as prime commander for Apollo 10, the final dress rehearsal for Moon landing. In 1975, Stafford made his fourth and final mission as the American commander for Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the joint mission with the Soviet Union. White’s technical assignment involved overseeing flight control development. He served as the pilot for Gemini IV, during which he conducted the first American spacewalk. He served as the backup command pilot for Gemini VII, before his assignment as senior pilot for Apollo 1, the first planned Apollo crewed mission. Tragically, White died in the spacecraft fire during a training session on the launch pad. Slayton assigned Young to oversee the development of the Gemini pressure suits. On his first crew assignment, he served as pilot for Gemini 3, the first crewed mission of the program, then as backup pilot for Gemini VI, before making his second flight as command pilot for Gemini X. In the Apollo program, Young served as backup command module pilot for Apollo 7, flew around the Moon as command module pilot during Apollo 10, backed up Lovell as commander of Apollo 13, walked on the Moon as Apollo 16 commander, and finally served as backup commander for Apollo 17, the final Apollo Moon landing mission. Young stayed with NASA through the early years of the space shuttle program, commanding STS-1, the inaugural flight of the program, and STS-9, his sixth and final mission and the first flight of the European Space Agency-built Spacelab science module. Before the Challenger accident, Young had been assigned to what would have been his seventh mission, but the accident disrupted the program and changed many crew assignments.

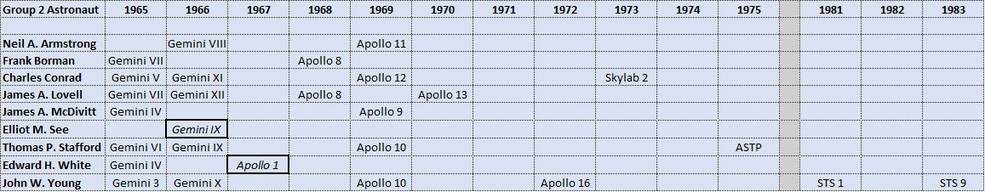

Summary of spaceflights by Group 2 astronauts. The highlighted boxes with flight names in italics

represent astronauts who died before they could undertake the mission.

By Slayton’s own account, the Group 2 astronauts comprised, “the best all-around group ever put together,” and their contributions helped America achieve President Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon. They flew 25 space missions among them, during the critical Gemini program that demonstrated the key techniques required for lunar missions, as well as the Apollo and even later programs. Two-thirds of the nine-member group traveled to the Moon, two of them twice, and one-third left boot prints in the lunar dust. The first of the group to make a spaceflight, Young in March 1965, also made the last, in November 1983, his then record-breaking sixth mission. Two made the ultimate sacrifice for the nation’s space program.