“Houston, we are returning to Earth!” With those words, Apollo 10 Commander Thomas P. Stafford announced that the Trans Earth Injection (TEI), a 165-second burn of the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine had been successfully completed while the spacecraft was behind the Moon and out of communications with Earth. Stafford and his crewmates Lunar Module Pilot Eugene A. Cernan and Command Module Pilot John W. Young had completed 31 orbits around the Moon during 61 hours and 37 minutes. Stafford and Cernan had tested the Lunar Module Snoopy and flown it to within 47,000 feet of the lunar surface while Young remained aboard the Command Module Charlie Brown.

Within minutes after TEI, the astronauts began a live color TV broadcast, providing lively commentary while showing viewers on Earth excellent scenes of the rapidly receding Moon. They also took some remarkable photographs. The apparent size of the Moon visibly decreasing during the course of the broadcast prompted Capcom Joe H. Engle to say, “You guys are really hauling the mail out there.” By the time the 53-minute broadcast ended, Apollo 10 was 3,900 miles from the Moon, but also slowing down as lunar gravity continued to exert its force on the spacecraft. Less than an hour later, the excited crew resumed their TV commentary, again showing the now slightly smaller Moon. After the seven-minute broadcast, the tired crew placed their spacecraft in the Passive Thermal Control (PTC) or barbecue mode to even out temperature extremes and settled down for their first sleep during the coast to Earth.

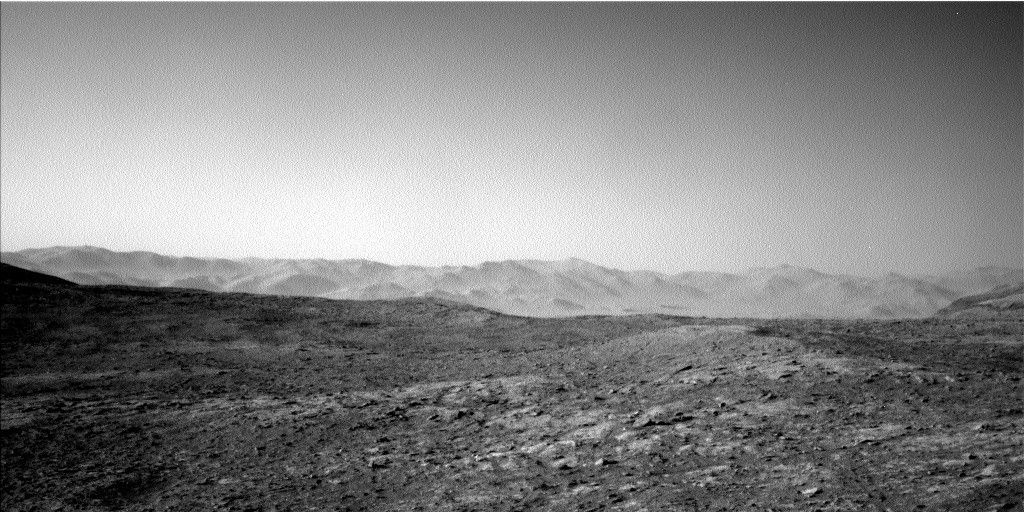

Two views of the receding Moon, taken from Apollo 10 shortly after TEI. Left: Primarily a view of the lunar

farside. Right: Mare Crisium is the large dark feature at left.

Two more views of the receding Moon, showing shadows along the day-night terminator on the

left edge of the Moon. The Sea of Tranquility is the large dark area near the Moon’s left limb.

Early the next day, Capcom Jack R. Lousma informed the crew that the TEI burn was so precise that the first planned midcourse correction during the coast to Earth was not needed. The crew conducted their next TV transmission, showing both the Earth and the Moon, with the Moon appearing about twice as big as the Earth, still some 210,000 miles away. Since the spacecraft was still in PTC mode, the Earth and Moon passed progressively through the spacecraft’s windows as it slowly rotated on its vertical axis. About an hour after the 11-minute broadcast, Apollo 10 entered the Earth’s gravitational sphere of influence and began accelerating. During their next TV broadcast about five hours later, the crew not only showed the Moon and Earth, now appearing to be about the same size, but turned the camera into the interior of the spacecraft. Young was clearly seen wearing a patch over his left eye to aid with dark adaptation for navigation sightings. Stafford and Cernan were also featured during the 29-minute broadcast. The crew then turned in for the night.

The next morning, Lousma informed the astronauts that the previous day the Apollo 11 crew had completed their water egress training in the Gulf of Mexico, including donning the Biological Isolation Garments (BIG) they would wear following splashdown to prevent any possible lunar microorganisms from escaping into Earth’s environment. The BIGs were a part of an overall quarantine program NASA established for all astronauts returning from Moon landings to prevent any possible biological contamination of the Earth. The rest of the day in space was relatively quiet, taken up with housekeeping and navigation duties. The only activity of note was that Stafford, Cernan, and Young became the first astronauts to shave in space, using brushless shaving cream. After Apollo 10 passed the halfway point in its return trip to Earth, the crew broadcast a TV transmission lasting about 10 minutes, showed the shrinking Moon and the growing Earth, and included many comments from the crew extoling the virtues of a space shave. Soon after, the crew settled down for their final sleep period in space.

View of the Moon (left) and Earth (right) at roughly the point when Apollo 10 crossed into the Earth’s

gravitational sphere of influence.

Left: Stafford at left and Young (upside down) at right during a TV transmission from Apollo 10.

Right: Cernan from the same TV transmission.

The first significant activity for their last day in space was the final color TV broadcast from a distance of about 43,000 miles from Earth. The 12-minute transmission included views of the now much larger Earth as well as comments from Young, Cernan, and Stafford summarizing their perspectives on their mission, finally closing by showing photographs of the Peanuts© characters Charlie Brown and Snoopy, after whom the crew named their spacecraft. Soon after the TV broadcast, the crew conducted a small midcourse correction maneuver, the only one required during the trans-Earth coast thanks to the very precise TEI burn. The nearly seven-second firing of the SPS engine refined the spacecraft’s trajectory for reentry and also reduced the g-forces the crew felt during the rapid deceleration. At the time of the correction burn, Apollo 10 was still some 30,000 miles above the Earth, and traveling at about 8,000 miles per hour, but the distance was rapidly decreasing as the spacecraft’s velocity increased. Less than three hours later, the crew separated the Command Module (CM) from the Service Module and turned its blunt heat shield into the direction of travel. By the time it made first contact with the Earth’s atmosphere 16 minutes later at an altitude of 400,000 feet, the point called Entry Interface, Apollo 10 was traveling at 24,791 miles per hour, the fastest reentry for any crewed space mission. To this the day, Stafford, Cernan, and Young hold the record as the fastest humans.

Apollo 10 floating beneath its three main parachutes, just moments before splashdown in the Pacific Ocean

east of American Samoa.

Apollo 10 reentered the Earth’s atmosphere on the night side over the southwest Pacific Ocean and continued northeast toward its splashdown target. The spacecraft entered a radio blackout period a few seconds later, caused by the buildup of ionized gases as a result of rapid deceleration. The blackout period lasted about three minutes, during which the crew experienced up to 6.7 gs of deceleration forces. At about 24,000 feet altitude, two drogue parachutes deployed to provide initial deceleration, followed at 10,000 feet by the three main parachutes that provided a splashdown velocity of about 22 miles per hour.

At precisely 11:53 AM CDT on May 26, 1969, Apollo 10 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean 460 miles east of American Samoa. The splashdown occurred shortly before sunrise, just 1.5 miles from the targeted point and 3.3 miles from the prime recovery ship the Landing Platform Helicopter USS Princeton. Stafford, Cernan, and Young had completed a flight lasting 192 hours and 3 minutes. Within 39 minutes, recovery forces delivered the trio to the deck of the Princeton, where they were greeted by the ship’s skipper, Captain Charles M. Cruse, and dozens of cheering sailors. After a brief stay aboard the Princeton, Stafford, Cernan, and Young were helicoptered to Tafuna International Airport, Pago Pago, American Samoa, where they were greeted by Governor Owen S. Aspinall, his wife Taotafa, and 5,000 Samoan well-wishers during a brief ceremony. From there, they took a C-141 transport aircraft back to Ellington Air Force Base in Houston, where they were reunited with their families and welcomed by a cheering crowd. The CM Charlie Brown was offloaded from the Princeton in Hawaii on May 31, flown to Long Beach, California, on June 4, and then trucked to the North American Rockwell plant in Downey to undergo postflight inspection. Charlie Brown is currently on display at the London Science Museum.

Left: Apollo 10 astronauts being helped out of the CM by Navy recovery swimmers while a helicopter hovers

ready to hoist them aboard. Right: Apollo 10 astronauts (left to right) Cernan, Stafford, and Young exiting the

recovery helicopter on the deck of the USS Princeton.

Left: Apollo 10 crew of (left to right) Cernan, Stafford, and Young during welcoming ceremonies at Pago Pago,

American Samoa,with Governor and Mrs Aspinall. Right: Apollo 10 crew (left to right) Young, Stafford, and Cernan

upon their return to Ellington Air Force Base in Houston.

Apollo 10 did indeed sort out the unknowns, as Stafford had promised prior to the mission. Stafford, Cernan, and Young completed the dress rehearsal for the lunar landing mission, proving the operations necessary for navigating two spacecraft independently in lunar orbit. Their color television broadcasts throughout the flight brought the experience into everyone’s living rooms. The mission encountered very few anomalies, and those were easily and quickly corrected for the next mission, Apollo 11, the first mission to land humans on the Moon. Apollo 10 ensured that the goal that President John F. Kennedy’s set for the nation in 1961 to land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth was within our grasp.

Apollo 10 CM Charlie Brown on display at the London Science Museum.

Credits: Don Thomas.

Enjoy a video summary of the Apollo 10 mission at: https://archive.org/details/apollo_10_to_sort_out_the_unknowns

Read Stafford and Cernan’s recollections of the Apollo 10 mission in their oral histories with the JSC History Office.