“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

On Episode 101, NASA historian Jennifer Ross-Nazzal shares some of the lesser-known stories of the Apollo 11 mission 50 years after the historic landing of humans on the Moon. Alumni from NASA’s Apollo program share memories from their unique roles in those missions. This episode was recorded on June 26th, 2019.

Check out the Houston, We Have a Podcast Apollo Page for all of our Apollo 50th anniversary episodes.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, We Have a Podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center. Episode 101, “Lesser-Known Stories of Apollo 11.” I’m Gary Jordan and I’ll be your host today. If you’re familiar with us, this is where we bringing scientists, engineers, astronauts, historians, all to let you know the coolest stuff about what’s going on right here at NASA. And sometimes we take a moment to reflect on what we’ve done in the past. Chances are you, at the very least, know the highlights of Apollo 11–

Neil Armstrong: Houston, Tranquility Base here. The eagle has landed.

Charlie Duke: Roger Tranquility, we copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.

Walter Cronkite Armstrong is on the moon. Neil Armstrong, 38 year old American, standing on the surface of the moon on this July 20th, 1969.

Neil Armstrong: It’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

Host: It was a harrowing journey to get there but NASA persevered and got the job done by the end of the decade. They did it– Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin– took the first steps on the lunar surface. You can probably look anywhere– books, documentaries, movies, articles– and really dive deep into that mission normally told by recognizable figures– Armstrong and Aldrin, Mike Collins, Gene Kranz. What you might not have heard are the stories of people working on the space shuttle before the moon landing even happened, monitoring the lunar space walk from the back rooms of Mission Control. And the recovery operations after landing. The arrival of the moon rocks at the Johnson Space Center. Stories of the many others who were helping to make this mission successful but that you may not have heard before. To recount stories behind the scenes of that historic mission we’re bringing in some very special guests. Returning to the podcast once again is Dr. Jennifer Ross-Nazzal, our historian here at the Johnson Space Center. She’s worked on oral history projects here interviewing many people to capture the lesser-known stories, so she’s coming on the podcast today to talk about some of these great adventures. We also shot a video a few months ago at Rice Stadium. We had such a great turnout for this video and it turned out to be partially a reunion for the nearly 50 Apollo alumni that excitedly agreed to participate. And while we were there, we tag teamed with Rice University to film as many Apollo alumni as we could in a short amount of time for them to tell their stories and we’ll share those here today. So starting with Jennifer Ross-Nazzal, here are some of the lesser-known stories of Apollo 11 told 50 years after the historic landing on the moon. Enjoy.

[ Music ]

Host: Jennifer Ross-Nazzal, thank you so much for coming on the podcast. Once again, you are among the elite here coming on three times so I really appreciate all of the time you’ve dedicated to us.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Oh well thank you so much for inviting me. It’s an honor.

Host: And it’s been 50 years now since the landing of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon. And of all the topics, you know we’ve thought about this for a while, what do we really want to explore to celebrate the Apollo 50th because NASA is doing a lot all across the agency, so what can we do here on the podcast? And I thought this was such a unique topic to explore. The lesser-known stories of Apollo 11. Things that– you might hear the recognizable story, one small step for man– you know you might hear that a lot of times but I think this is a great medium to explore some of the other ones. So Jennifer, you’ve put together really a fantastic list of stories that go from even before the moon landing, through the moon landing, ’til after the– I think we’re going to end with one of, I think my favorites, after going over this so I’m really looking forward to it. I think I want to kick off though, let’s talk about, you know, what do we have in store actually before we even go into that? What do we even have in store for us today?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Well, as you mentioned I tried to pull together some of the unknown stories of Apollo 11. We all know the Gene Kranz story, the lunar landing mission and his talk before the MOCR crew, and you know he’s with them 100% whether we land or we don’t, I’m with you. And we know a lot of what was going on with the crew. We don’t know a lot of the stories though about the people behind the scenes and so I tried to pull together some of those stories. And also, like you mentioned, pull together a story pre-mission and then some of the things that were going on during the mission that aren’t, weren’t as notable but today I think are quite interesting. They’re sort of human stories that I think people will engage with. And then the post flight, what was going on like in the LRL and the mobile quarantine facility.

Host: That’s awesome. Yeah so some of these names you’re going to be hearing today are names you may have never heard before. I do think though you do have one name that I’m pretty familiar with, Michael Collins.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes. [laughs]

Host: [Laughs] Of course he was the one, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, we always say those names right up front because they were the ones that had the boots on the moon, but someone had to be in the command module up orbiting the moon. And guess who that was? It was Michael Collins.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes.

Host: So what did– let’s see, he might have a little lesser-known story I suppose.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: You know he does, and it’s something, I was flipping through “Carrying the Fire” which is his autobiography, and I was just looking for stories and I came across a poem that his wife wrote to him before his mission. He actually took the day off before the flight which we always think the astronauts are working madly up until their mission and once they climb into the cabin they’re kind of done but he decided to take the day off and he called his wife– his wife was not there– and had a chat with her and kept rereading her note to him and the poem that was attached to it. So I thought maybe your readers would like to hear this poem that she wrote to him.

Host: Oh that is wonderful, yes. Let’s go through that poem.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Okay. So this is called “To a Husband Who Must Seek the Stars.”

In your eyes, the first glad token

As when first our love we proved,

So your mind to mine has spoken

Just as if you’re lips had moved.

You are saying — yes I know —

That the lure of space beguiles.

You are pleading, “Let me go,”

Not unwilling but with smiles.

Can you love me, and still choose

Whispers that I cannot hear?

Late to love, how can I bear to lose?

Content for some inconstant sphere?

Tell me how you see my role-

To stay, to wait, yet yearn to go.

Where is the comfort for my soul?

You, my love, have helped me know.

I’ll be unafraid, undaunted.

Yes of course! I need not face

Any peril; or be haunted

By the hazards you embrace.

I could’ve sought by wit or wile

Your bright dream to dim. And yet

If I’d swayed you with a smile

My reward would be regret.

So, for once, you shall not hear

Of the tears unbidden, welling;

Or the nighttime stabs of fear.

These, this time, are not for telling.

Take my silence though intended;

Fill it with the joy you feel.

Take my courage, now pretended–

You my love will make it real.

And he wrote in his book, I hope I will.

Host: Wow. So that was, I guess it was her way of saying you know you need to do this mission, don’t worry about me. You know I’m not going to stop you. This is kind of your destiny almost.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah and to me it’s, she’s also telling him while she might be scared she’s not going to share those feelings with him.

Host: Yes.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: She wants him to have this opportunity. She doesn’t want him to have any regrets or herself to have any regrets.

Host: But she was open with that emotion to him even– because you said this was even before his mission.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: It was.

Host: She said know that I am scared but it’s not going to stop you, it’s not going to stop me from stopping you. And even if I did, I would regret it.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. Yeah.

Host: Wow. What a beautiful way to say that. And you said that Michael Collins was on the phone with her reading back her poem to him on the phone?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Well no I think he was rereading it in crew quarters.

Host: He was rereading it in crew quarters?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah and–

Host: I see.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: You know he mentioned how clearly she had been thinking about this for some time. It wasn’t just a note, you know, kind of I love you, good luck on the mission. Clearly she had thought about this for some time and been working on it.

Host: Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: What all did Michael Collins do on his day off before his mission, do you know?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: You know, what else he did, I don’t know. [laughs] He just mentioned that which I thought was interesting.

Host: He just– yeah. That was probably one of the more significant things. If you’re going to remember anything, that’s a beautiful thing to remember.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes.

Host: All right Jennifer, I’m really excited to go into these stories. To sort of kick things off though these stories are from something that your office does and the Oral History Project. Tell me a little bit about that.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah so we have a major oral history project at our center. We’re sort of the lead center for oral histories across the agency. And our project was established by Center Director George Abbey in 1996. And if you’re interested in more of the history you can actually go out and read an interview with Duane Ross who sort of helped kick off the project. But I’ll give you a little bit of history. Mr. Abbey was a big fan of Stephen Ambrose. He wrote a number of books that were quite popular in the 90’s like “D-Day”. He wrote about Lewis and Clark and some other folks. And so he was a big fan of his efforts at interviewing these veterans and he realized that we were losing a lot of folks here at JSC who took part in the Apollo Program, Mercury, Gemini, and he wanted to capture those experiences. He wanted to capture the procedures and processes but also the events and the career experiences of some of these individuals or lessons learned. And so that project kicked off in 1997. The first interview was with Jack Kinzler who we’ll be talking a little bit about today as well, and you know he was well known at the center for being a Mr. Fix It and saving Skylab, and but he was our first in the summer of 1997. Since then we have interviewed 982 people.

Host: Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: We have over 2,000 recorded hours of oral history. We’ve done over 1,200 sessions and we have over 1,000 transcripts online.

Host: Whew! It’s got to be difficult to remember all those stories. That’s why you’ve got to capture them, right? [Laughs]

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes, exactly. And everybody’s got a story.

Host: Yeah, and they span– this is not just Apollo history right? They span through the– is it the agency’s history? Is it Johnson Space Center’s history?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Well we actually do a lot of different oral history projects. So interesting that you mention that. We do our JSC Oral History project and it does span from the Space Task Group days through International Space Station, Orion. We’ve tried to capture all of that history and everything in between. But we do do oral histories for NASA headquarters. So we do interviews with administrators or center directors, people that our headquarters history office wants us to talk to. And then we’ve done different projects over the years that we’ve received funding for. Like for instance when the shuttle was retiring we did a big project to capture the history of the space shuttle from development through retirement which was a huge effort. Can you imagine, you know, 40 years of history–

Host: Right.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: in oral histories?

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: 30 years of shuttle but you’re talking about development stage right?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes.

Host: Yeah and there’s a lot of years there.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah there’s a lot going on. So we’ve got that. We’ve captured some history of aviatrix. Let’s see, we’ve captured a lot of women’s history with the Herstory’s project. So there’s quite a bit out there if people want to go out to the JSC history portal and look at the oral histories, there’s just so much material out there. It’s such a wealth of material from these people that we’ve interviewed.

Host: Very exciting. And today we’re going to be focusing on mainly the time around Apollo. And I think when we were going through these stories together, I think you kicked it off in such a nice way because the first thing we’re actually going to talk about is the space shuttle which a lot of people don’t even recognize was a thing around the time of Apollo 11. So this one was with Jerry Ross and Kathy Sullivan.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah so Jerry Ross, he’s very well known for the number of space flights that he flew on. He’s actually the record holder of seven space flights along with Franklin Chang-Diaz. And Kathy Sullivan was one of the first six women astronauts selected 1978 and she’s the first American woman to do a space walk. So, you know, very well known folks. I picked these stories because I just thought they were interesting. I thought it was important to highlight the fact that there were people who were going to be working in the program later in life who were witnessing and remembered these and shared these memories with us. So Jerry Ross, he remembers, he was in college at that point. Since fourth grade he wanted to be an engineer and go to Purdue. And so this was summer break and he was working for U.S. Steel. And he remembers just sitting on his couch with his fiancée on his lap just waiting for that first spacewalk to happen on the moon, and being very excited about it. He also remembers his younger sister taking snapshots of the television. And you know it was pretty grainy, kind of hard to see, and he kept telling her you know those shots aren’t going to turn out but they ended up turning out. But he was just, you know, mesmerized, he said by the whole mission itself. His fiancée found him just sort of sitting there watching, you know, endless footage of Mission Control and what was happening. And then Kathy Sullivan I think is sort of interesting because she really didn’t intend initially to study science or, you know, work for NASA. She wasn’t going to be an engineer. She had an interest in language and so she was actually going to study languages in college. But she remembers she was 17 at the time sitting in her family den– you know I can kind of see her sitting on the floor the way most kids do watching TV– and she remembers she wasn’t really a spectator for this event, she was almost like a part of it she said. It just sort of drew her in and she remembers hearing Buzz Aldrin, although she admits she wasn’t sure who it was at the time because she really wasn’t following that closely, say contact light. And she said you know there was just this sort of spark in her mind like oh, she made a connection as to what was happening here. They had something that she called curb feelers on the lunar module so they could tell where they were on the moon. And she said it just sort of made an imprint on her that, you know, she kind of figured out some of the engineering going on there with the Apollo Program.

Host: Wow, it sounds like such a subtle thing but even these shuttle astronauts were inspired by some of the early parts of NASA history. Actually we’re going through right now and interviewing some of our leaders here at the Johnson Space Center talking about, you know, how were you inspired to come here and did Apollo 11 have a significant impact, and all of them– not all of them but a lot of them– remember very vividly what they were doing. And a lot of them, you know, they were, a lot of them were kids so they went out and they got like some kind of moon thing that was at the grocery store or the convenience store but it was just fascinating what– you know how much this inspired people. Now speaking of space shuttle and this is kind of what I think I alluded to in the– before you even started with the Jerry Ross and Kathy Sullivan story, but space shuttle was a thing even before Apollo 11 landed.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes. Yeah. So I was going through some of our stories and I wanted to make sure we included some women because during the Apollo Program there weren’t a lot of women working or at least most of the women were secretaries and admins and we haven’t had a chance to talk with them but we’ve interviewed Ivy Hooks and Dottie Lee and they were some engineers working in the engineering directorate. And Ivy Hooks likes to tell the story how on April 1st– April Fool’s Day 1969– so we haven’t landed on the moon yet, she gets a phone call from Max Faget’s secretary and tells her to report to building 36, they’re going to have a meeting there and they all thought it was kind of an April Fool’s Day joke. And so they show up there and she’s like what’s going on? You know it’s the third floor. There’s a lot of furniture in this space. This space hasn’t been used. It’s kind of dirty, I’m wearing white. Max Faget walks in and Dottie Lee also remembers this– she was an actual engineer trained by Max Faget– she originally started out as a human computer out at NACA in Langley. And they both remember him pulling out of this garment bag a space shuttle, a balsa wood plane, and throwing it across the room and saying we’re going to build America’s next spacecraft. It’s going to launch like a rocket and land like a plane. And so these two women– they were the only two women other than the secretary– were in this space, they were locked up. They couldn’t actually tell anybody where they were or what they were working on or what they were doing, and they were helping to design the first reusable spacecraft, the space shuttle. And there weren’t any windows. You know it was kind of a big deal for Ivy. [laughs] But what I find interesting about this is we’re working on the next spacecraft while we’re still working to land a man on the moon. And interestingly enough, Dottie Lee remembers that because she was in that room and had told herself, she had promised herself when we got back from Apollo 11 she was just going to celebrate. She was going to, you know, party like everyone else. Everyone else was so excited and she remembers she worked late that night.

Host: Oh.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And she was in her car. And her husband also worked out here, John Lee, he was also an engineer. And she was driving home on NASA Road 1. She lived in Dickinson and she remembers seeing cars everywhere. Everyone’s at the bars. Everyone’s celebrating and she couldn’t. She had to drive home and relieve her babysitter so it was kind of, you know, a sad moment I think for her because she had helped accomplish this goal but she had other important things to do. She had two daughters at home–

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: and but she said you know it was exciting for her though because she felt like she was contributing to tomorrow today by working on the space shuttle.

Host: That’s right. And it made a significant impact. We already said, you know, like there’s 30 years of the shuttle flying and even before that development stage starting in April when Max Faget pulled out a small space shuttle and said this is what we’re going to do now.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Um hum. Absolutely.

Host: Who was Max Faget by the way?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Max Faget was our spacecraft designer here at the Johnson Space Center and so he helped design the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo capsule. So he’s very well respected.

Host: A good salesman too if he’s doing this–

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: to get everyone to start working. That’s great. [laughs]

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. Yeah. And I should add that Dottie Lee actually is known for helping design the nose of the space shuttle. It’s called Dottie’s nose.

Host: Really?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes.

Host: Okay. The space shuttle, I guess, well was it the space shuttle as we know it or was it–

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes.

Host: Really?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: Wow, that’s a big deal.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: It is a big deal, yeah.

Host: Very busy people I’m sure all across. I know everyone was working real hard on this and that includes, you know, you said Ivy Hooks, she wanted to celebrate and was working late but she also was a mom and that was part of it, relieving the kids.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. Yeah Dottie. Dottie was.

Host: Yeah. Oh Dottie, it was Dottie that did it. Oh I’m sorry.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah that’s okay. Yeah Ivy doesn’t have any children that I’m aware of. [laughs] Don’t worry about it.

Host: I messed that up, sorry.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: That’s okay.

Host: You know now we’re getting into, you know, the actual moon landing. I like this story from Bob Carlton with the stopwatch. That is a great story.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. Yeah so Bob Carlton was LEM control. He’s working in the mission operations control room and he’s on the white team which is Gene Kranz’s team. So some people might know this story but I think it’s just a great human story because I think they probably know about the challenges that the flight controllers were facing in the room but there’s another aspect to it that I’ll talk about. So before the mission happened he was, you know they would simulate these missions, they would make sure that everything was running properly, and in his oral history he talks about the fact that they had plenty of margins in the lunar module tanks when they were going to be coming down. They were going to have plenty of fuel to land on the moon. They would have plenty of fuel left. But when they were landing Apollo 11 something happened. Neil Armstrong as he’s landing the lunar module sees a huge crater where they’re supposed to land and there’s boulders. And so suddenly that margin that they had really starts to go down pretty quickly. And so they’re watching things. He’s watching it. And they weren’t supposed to trip something that they called low level inside of the lunar module. They had two ways of telling how much fuel they had. They had something like a gas gauge that would tell them, you know, full, empty, and somewhere in between. And then they also had this low level sensor. And once you hit that you only had so many seconds left of fuel. Well they ended up tripping that and so Bob Carlton pulled out a stopwatch and he talks about in his oral history how he put something very technical– he put a couple pieces of scotch tape on his stopwatch–

Host: [Laughs] Yes, very technical.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: [Laugh] Yeah, very technical. So he clicked it and he said okay when it gets to 60 seconds it’ll be here and when it gets to 30 seconds it’ll be here and we’ll only have just a little bit of time left. The other challenge that he was facing was that you couldn’t go to the moon and leave the tank empty. They had to be able to call an abort and have some fuel left. And so he said he was just watching it so intently, you know? Every– once they got down to that low level like people were just sweating in the MOCR and it was just so quiet. And so they got to 60 seconds. And he’s starting to doubt whether or not they’re going to be able to land. And then they get to 30 seconds and he said finally they landed and he clicked the stopwatch. 18 seconds left of fuel.

Host: Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And so you know we often remember Charlie Duke telling the astronauts, you know, whew you got a bunch–

Host: You’ve got a bunch of guys about to turn blue, yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes and you know Bob Carlton really was that guy because he knew that at some point they probably were going to have to call an abort and he wasn’t really sure they were going to be able to land at this point. So what’s interesting though about the story, the sort of human aspect that I think is interesting is that he sees the stopwatch and he thinks what a great memento, what a great artifact of this mission. And so he takes it back to his office and he puts it in his desk because he wants to remember this moment. And you know he pulls it out occasionally but then he realizes well, you know, I probably shouldn’t keep it at work because a janitor or somebody might come in my desk and just take it.

Host: Right.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: So I’m going to take it home. So he puts it in a handkerchief and he carries it home and he puts it in a desk at home and occasionally he pulls it out. Well he pulls it out one time and he looks at it and he said, I must be losing my mind here because it should be at 18 seconds, it’s at like 22 seconds, but he doesn’t think anything of it he just puts it away. You know how all of us do that, we might have a trophy or a picture we’ll look at it and put it away. And so he pulls it out again and it’s on a different time this time. So he approaches one of his daughters who was a twirler and you know he asked her what’s going on? Well it turns out she was using the stopwatch for her routines to time them and he was like oh okay that explains it. Well eventually he decided, you know, this was a great artifact, it needed to be somewhere else not in his house. So he donated it to the Smithsonian but he ended up winding the stopwatch back to 18 seconds–

Host: Oh.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: So, you know, it would look like it did when they landed on the moon.

Host: Right. Right. That’s where it ended up but–

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right.

Host: but little do people know this was used for twirling exercises.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right. Exactly. Yes. [laughs] I just think that’s a great story because I think so many people can relate to that, especially with kids. You know you tell your kid don’t touch this, and what does your kid want to do immediately? Touch it or–

Host: That’s the only thing I want to touch now.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Exactly. Yes.

Host: Wonderful. Yeah you have– that’s a big story. You have a bunch of guys about to turn blue here because everyone was waiting. They had to– they couldn’t land in the area they were supposed to land, they had to find a new place to land which is why they were using all of these, all of this fuel. But it wasn’t just those people in the primary Mission Control. You know a lot of people don’t realize there are other rooms looking at other things. Even after they landed there’s a room called the Mission Evaluation Room.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right.

Host: Right? And there’s, I like the story of Tom Sanzone monitoring the EVA. We actually got to interview him not too long ago at Rice Stadium. It was actually a weird coincidence that you have his–

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Oh great.

Host: his name here. We have this great video where we have all these different Apollo alumni, current employees, astronauts, former astronauts and we gathered to celebrate the 50th anniversary but also remember John F. Kennedy’s speech in ’62 there on the field. And it just turned out to be this great thing. We pulled a couple people aside. Tom Sanzone just happened to be one of them. He has a great story because he was one of the portable life support system engineers right?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right, yeah.

Host: Yeah. So what was he doing in the MER?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah so interestingly enough he was out in Pasadena originally because he was told to go home and get some rest because of course they were going to be monitoring the backpacks while they were doing an EVA on the moon. So he remembers being home, you know, sort of waiting. You know everyone was anticipating this moonwalk and the landing so he watches it at home on his television but then he’s called and told to report for duty because they decided instead of a rest period the astronauts actually want to go out for a spacewalk. So, you know, he comes in and he said there were probably about eight people in the Mission Evaluation Room from Hamilton Standard which is who he works for who was in charge of that system. And you know it’s kind of interesting, like I said, it’s the support room for Mission Control but they’re monitoring the backpacks for the astronauts. So he’s monitoring Armstrong and there’s another guy who’s monitoring Armstrong’s data as well and then they have two other engineers who are monitoring Buzz’s backpack. And, you know, that backpack is really their whole life support system. Everything that we take for granted on Earth, that’s what that backpack system provides. And so they’re monitoring lots of different things like the amps, the batteries, the oxygen levels, the pressure of the suit, lots of different things. They actually got their data on cathode ray tubes so things would come out on TVs and they would graph that data using magic markers, by hand you know? Things that we’re used to computers doing nowadays but they would do that by hand. They also had these displays with stopwatches because they wanted to make sure of course the astronauts are on the moon, the last thing you want is oh my gosh you know we have like 20 seconds left of oxygen, get in the LEM, you know?

Host: Yeah. Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: You want to make sure there’s ample oxygen and everything’s going fine. So you’re monitoring all of these things, all of these things with inside this space suit itself. And you know they are so focused on the task at hand, kind of like Bob Carlton was on that stopwatch, that Tom Sanzone doesn’t even remember seeing Neil Armstrong or Buzz Aldrin walk on the moon. He doesn’t remember that at all and he’s not even sure there was a TV in the room but they were just so focused.

Host: They were looking at the data.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Mm-hmm.

Host: They were– yeah they didn’t have time to look at the TV, they were looking at that stopwatch. Oh man they’re going out.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes.

Host: Yeah I remember talking to Tom Sanzone and the– I think the funniest thing I learned from that is I did not realize that once the astronauts landed, the next thing was a rest period, for them to take a nap.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes.

Host: And I remember Tom Sanzone when he was recalling this just laughing because he’s like can you imagine, you landed on the moon and you’re like hold on let me just take a quick nap.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right.

Host: Of course they were excited. They wanted to go right out. So, yeah of course they weren’t going to waste any time and oh let me just rest up a bit. They only had a couple hours really.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. Yeah it was about two and a half hours.

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: To be out on the moon.

Host: Right so obviously yes you have to take care of that period you know I’ll sleep later.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes. Well and you just imagine the excitement. You’re kind of like a little kid. I mean this is a new playground for you to go out and see a new world.

Host: Yes.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And experience all of that.

Host: And you know what’s great is they got to feel that way, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon, yeah I’m excited, let’s go out. But they had people like Tom Sanzone in the back room that was busy looking at a stopwatch and you know couldn’t, yes maybe he was excited but didn’t have time to go check out a TV because he had a job to do and it was, you know, folks like him that actually made that possible. So I love these small stories of people in the background. It’s amazing.

Real quick while we’re talking about Tom Sanzone, we actually got to interview him at Rice Stadium while we were there so here’s his version of the story.

[ Transition Sound ]

Host: Tom Sanzone, and what was your job during the Apollo program?

Tom Sanzone: I was a portable life support system engineer. That’s the backpack that they wore on the moon so I worked for Hamilton Standard was the name of the company then. It’s a United Technologies Company. So we did all the testing, modifications, maintenance, flight prep, astronaut training in vacuum chambers and things like that. So I was involved with most of that stuff.

Host: Okay. Do you have highlights from your time working in portable life support systems, something, some story that comes to mind?

Tom Sanzone: Yeah I smile because I’ve been asked this before and what I tell people is when I was 22 years old 10 months out of Villanova I got to train Neil Armstrong and the Apollo 11 crew on how to use that life support system and my career has been downhill ever since. [laughs]

Host: Do you remember where you were during the Apollo 11 moon landing?

Tom Sanzone: Yeah. For the landing I was actually in my apartment in Pasadena primarily because the crew was supposed to sleep after they landed on the moon and then go out for their walk on the moon after they woke up. So we were going to monitor the performance and so they didn’t want us hanging around and, you know, being tired so none of us really believed that they were going to sleep [laughs] you know so it wasn’t a surprise. So I watched by myself in my apartment in Pasadena when they actually landed and then shortly thereafter I got a phone call saying you know they’re not going to sleep, they’re going to go out. I– can you imagine sleeping on the moon when you just landed? [laughs] And so then I, you know I drove in and I worked in what’s called a Mission Evaluation Room, you know, one of the back rooms of Mission Control.

[ Transition Sound ]

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah I don’t think people realize how many people were working in the background.

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Just making sure everything was operating smoothly, you know? The astronauts get sort of all the credit and the attention but there were so many people that contributed to the Apollo Program in so many different ways.

Host: And this next story is a perfect example of that because this is the story of a guy who honestly didn’t even appreciate the landing on the moon until much later. I love this story.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah so Ed Fendell, he did an interview with our project years ago and he is on console also with Gene Kranz’s team. He’s the ENCO console. And he remembers as the landing is happening, he’s kind of levitating in his chair. And he knows that he wasn’t really levitating, but that’s kind of, it was just so surreal. He didn’t really think they were going to land on the moon the first time. He thought that maybe they would try but it wouldn’t happen. But it’s just so surreal he feels like he was levitating and you know they do the change of shift and he goes home. He decides to, you know, go back to his apartment, get some rest, cleans up, and decides to grab some breakfast before he heads in for work the next day. And he goes by what’s called a Dutch Kettle. It’s like a coffee shop and nearby his apartment and he decides to go sit at the counter. He’s got a newspaper with him and he orders breakfast. Said he ordered scrambled eggs. I’m sure he got some other stuff but he was sitting there and some guys walked in from a gas station down the street and, you know, you could tell because they were in their overalls and you know they’re kind of greasy, but they were talking about the Apollo 11 mission and talking about how they had been through World War II, they were at Normandy and D Day, they walked through Paris and made it to Berlin, and one of the guys said but yesterday was the proudest I’ve been to be an American. And Ed Fendell was sitting there and he heard that and it suddenly hit him what they had done. And he picked up his newspaper and left the restaurant and he started to cry and he just kind of lost it because until that point, you know he knew we landed on the moon but I don’t think it hit him, you know like it had hit so many other Americans across the globe who were just excited. Like Dottie Lee mentioned, so many people were at the bars celebrating. People were in Times Square. But it hadn’t hit this person who was in the MOCR who was so focused on getting the task done until this moment, what they had really achieved and what it meant to the citizens of this country. And he said he still has this paper til this day. You know he cried in his car and decided to come into work and but that’s just such a great moment. I mean it really speaks to what was happening with some of these guys in the MOCR. It was a great achievement but it didn’t really hit home initially–

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: what had happened.

Host: It– certainly that story gives me an appreciation for how focused these guys were. You know like it’s not just, they’re not just the front row seat for this whole thing. It’s way beyond that. It’s these guys that had their head buried in all of the data to make sure that the mission was going to be successful really just working hard to get the mission done and not truly realizing or appreciating the world around them and everything that was happening because you have guys looking at stopwatches, you have guys monitoring data, you have guys just making sure that after you know 18 seconds left of fuel that everything’s going to run smoothly and we’re going to get these guys home. You know it’s not just we landed on the moon. The mission’s not over at that point.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right.

Host: And it’s something that I think, you know even these human interest stories, these, and not even human interest but just these very human stories really, you know, help you to appreciate that.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Very much. And I should add, you know, a lot of people that we’ve talked to over the years who were part of the Apollo Program talk about how they were so singularly focused they didn’t really know what was going on with Vietnam or Civil Rights. All of these things that were erupting around the U.S. and the story that I always like to tell people is Al Bean who was the lunar module pilot on Apollo 12 said he didn’t really learn about all these things until much later thanks to the Discovery Channel. And this is before he came to NASA but he said he didn’t even know who Rosa Parks was. You know Rosa Parks, that was in like the 50’s.

Host: Sure.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: But I mean that’s a good example of just how involved they were in Apollo. Their noses were very deep into these subjects and they weren’t watching the news, they weren’t reading the papers, they were singularly focused on achieving the goal of landing a man on the moon.

Host: Yeah. Of course there was a lot going on in ’69 you know? This was definitely even to some of these guys were some of the most, one of the proudest American achievements landing on the moon but you did have Vietnam going on. I know a popular, was it a book or a movie, “The Andromeda Strain”?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah “The Andromeda Strain”, the book.

Host: It was a book, yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah by Michael Crichton, yeah.

Host: Yeah. So this next story about, is it John Hirasaki?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: John Hirasaki, yeah.

Host: John Hirasaki, “The Andromeda Strain”. That’s, that was interesting because that was the, almost, I don’t know, “The Andromeda Strain” is I guess about this virus that comes to Earth or something, right?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes.

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah I remember reading it– I haven’t read it in a while but I remember reading it in college and thinking oh this is crazy, you know, that you would have to– I think it was sort of based on this idea of a Lunar Receiving Lab and sort of going in and having to like burn your skin off when you would want to come out because of this bug that came to Earth and just this sort of scary environment.

Host: Yeah but it really helps you to put into perspective like that was a thing. People were very, you know, the moon, we were landing on the moon but part of the mission was getting all this stuff back and people had no idea what to expect. What is on the moon? So they were handling these things with such care because we don’t know. We can get a virus and bring it back, who knows?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right. Yeah, yeah. There was a big concern. A lot of people who worked at NASA weren’t as concerned because they thought the moon was a sterile environment.

Host: Sure.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: So initially when we were planning for the moon landing there wasn’t this idea of a Lunar Receiving Lab. That came a little bit later. You know we were really focused on engineering. But then scientists themselves who weren’t working at NASA became concerned that we were going to be bringing back people and rocks and soil from the moon and, you know, what impact would that have on plants? What impact would that have on humanity and animals? Could that have a detrimental impact? And maybe we need a quarantine facility. So that started the whole discussion about whether or not the crew needed to be quarantined and for how long and the safety of the planet and all of these concerns.

Host: Yeah we’ve had a couple podcast episodes so far with some of the folks in the lunar lab and other folks who study meteorites and I think one of the best things from the Apollo 11 mission was when Neil Armstrong, you know they had these containers that they were supposed to put all the rocks in, but after they put the rocks there was a lot of empty space. So what does Neil Armstrong do? He starts– he gets out the shovel and starts putting in some of the soil–

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right.

Host: from on top just to fill some of this empty space. You know, why not? So they’re on the moon and a lot of the folks say that that was some of the best stuff that they brought back with them. Not the rocks but the soil themselves. It revealed a lot about the moon and about Earth’s history.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: Very cool story. So what’s the story on Hirasaki?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah I’m going to sort of intertwine that with Randy Stone–

Host: Oh yeah.

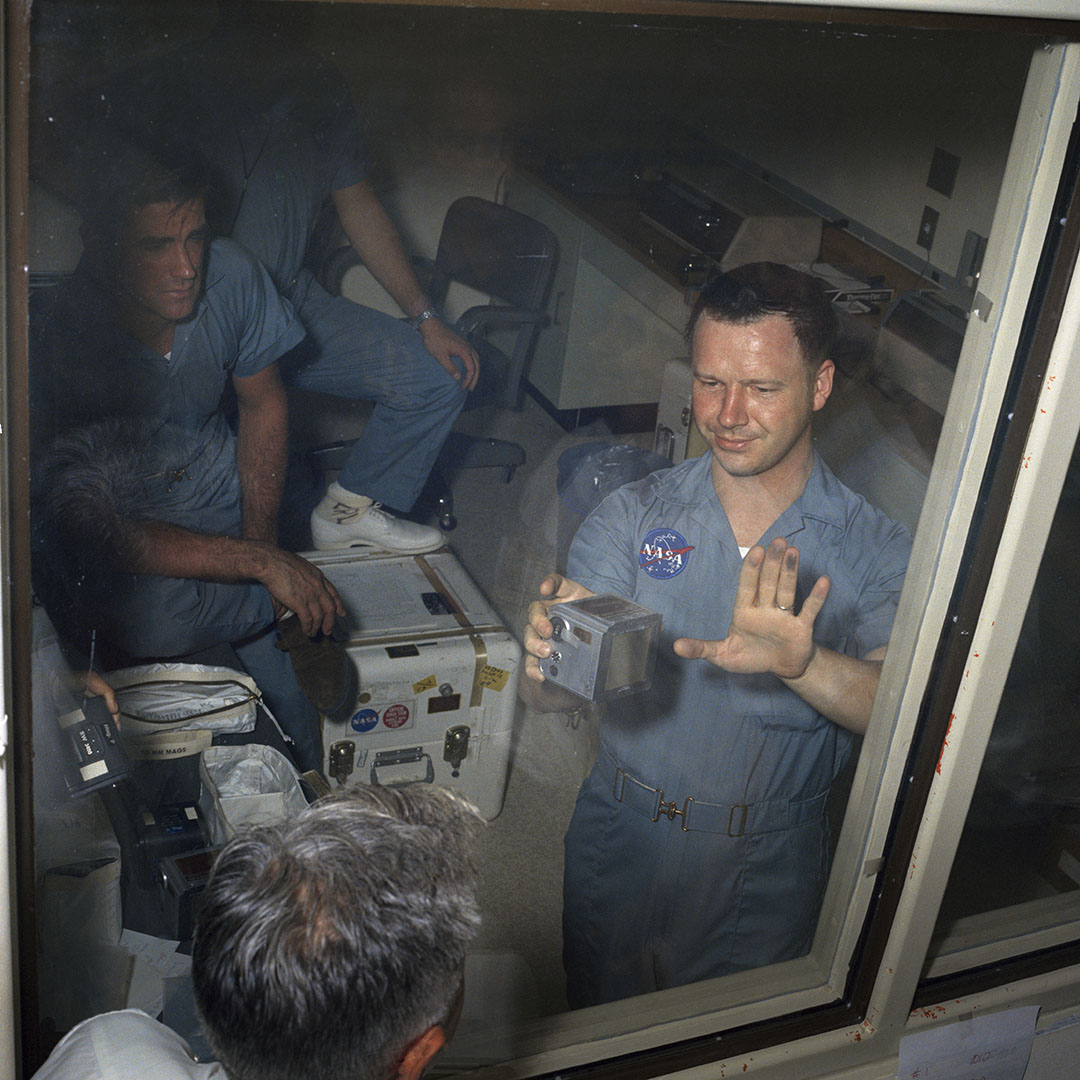

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: because they both worked for the landing and recovery division. They’re both young guys who came in and they’re both actually on the ship, the USS Hornet, which is the ship that’s going to pick up the crew coming back from the moon for the first time. And so they both work for the landing and recovery division. They’re both engineers. Randy Stone is the lead engineer for the folks outside of the mobile quarantine facility. And John Hirasaki is actually going to be quarantined with the crew that’s coming back inside the mobile quarantine facility. And so I want to just talk a little bit about Randy Stone first because I think it kind of gives an idea of what’s happening and then we can talk about John. We’ll probably go back and forth between the two.

Host: Sure.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: But he was on the ship for a while. You know they were practicing things. They knew that President Nixon was going to be coming on board and so they were practicing maneuvers and routines and trying to get things ready for when the crew was coming and for when the president was coming. When the president comes, he actually models the biologic isolation garment for the president which I wish I’d seen a picture of it. I haven’t been able to find a photo of it. But I, you know I think that’s kind of interesting that he would be working on these things. And John Hirasaki is placed on board but he’s placed inside of the mobile quarantine facility. They actually drew straws. There were four guys who were interested in being in that mobile quarantine facility. Even though, you know, there were fears about maybe bringing back a lunar bug and you know nobody knew what they might be bringing back and what impact that might have. He was actually a newlywed. He had married someone about six months earlier and so of course “The Andromeda Strain” is on her mind. But you know people wanted to make a contribution. People were willing to say, you know, hey I’ll participate. I would like to do that task. And so he got the short straw and was in the mobile quarantine facility. He was put in early because there were concerns that, you know, he might catch something from some of the crew on the Hornet and they didn’t want him to have any sort of cold or virus and give that to the crew themselves. And there was another person who was in the mobile quarantine facility and that was Dr. Carpentier, their physician at that time. So like you said, you know there were some concerns that they had but he’s, you know he’s got a front row seat. When the crew comes back he’s got a front row seat to hearing the stories that the crew would tell about landing on the moon for the first time which is really exciting of course because when you go somewhere exciting and interesting you want to come back you want to tell people all about it. And they’re locked in this quarantine facility because people are concerned, hey maybe you brought back a lunar bug. Maybe you’re going to infect humanity as we know it. So they’ve got a chance to actually sit and talk with the crew and they tell their stories. So here, we need to go back now to Randy Stone because John Hirasaki is in the mobile quarantine facility. They bring back the crew, they go into the mobile quarantine facility but they also need to bring back the command module. And inside the command module are things like the rocks, as you talked about. There are also photos that they need to get back here to Houston to process. And Hirasaki, that’s going to be one of his tasks. Well, Randy Stone is in charge of sort of safing the command module and, you know, there’s a lot of toxins on board and so they need to make sure that the reaction control system jets are safed. And they also need to attach the command module to the mobile quarantine facility which is a trailer essentially that they’re living in. And so they sort of snap it on but then he talks about how they’ve got hundreds of rolls of yellow tape. He said they used to joke that they couldn’t go to the moon without yellow tape. He said it’s like duct tape is today. You know–

Host: Oh.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: you just use it for everything. And so, you know, they had to seal up the command module with all this yellow tape so there would be a good seal. Even though it snapped on they wanted to make sure nothing made its way out. You know they were very concerned about that trying to protect, like I said, humanity and animals and plant life here all across the globe. Not just Americans themselves. And so once they had done that, John Hirosaki was able to go into the command module and do some of the things that he needed to do. One of the first things that he mentioned that he had to do was take photographs of the command module, the interior. This is what it looked like before anybody touched it. You know this is where the switches were. This is how things, where things were located. And so he did that and then he reaches in and he grabs the rock boxes which you mentioned, and he also grabs the magazines, the photos that the crew had taken because here in Houston they want both of those things. And then there’s also a beta cloth bag of luner rocks that they’re going to take with them back in the mobile quarantine facility. Interestingly enough though, he has to take those boxes and he has to vacuum seal them before he can give them to Randy Stone because Randy Stone is going to take those boxes and put them on a carrier. But they need to be decontaminated because of course they’re in the command module so he vacuum seals them and then puts them in a decontamination lock which Randy Stone describes it as using a, you know, a really toxic Clorox solution because they have to be rinsed and washed. And he said that, you know, it would hurt your hands. It would stain your clothes. It smelled horrible. But you wanted to make sure of course you killed everything. So he said, you know, his most memorable moment though was getting that box– those boxes which were made here by our tech services people– and taking them with the Marine guard. He said he thought it was rather funny, he’s on a Naval carrier but he’s got Marine guards with him taking it to the plane as if anybody’s going to jump on him and grab these lunar rocks. And he said that was probably his proudest moment. But then John Hirosaki remains in that mobile quarantine facility. And interesting enough, he’s sort of the chef and bottle washer is what he likes to call himself. Of course they had to eat and they had something new in that mobile quarantine facility, a microwave. They had an Amana Radarange which a lot of households– nowadays everybody has a microwave but at that point a lot of households didn’t. And so he was actually in charge of picking out the kind of meals that they would have in the mobile quarantine facility when they were doing tests. People wanted them to have like fancy meals like Lobster Thermidor and other things–

Host: Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: and he was like nah, I think we need something else.

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Maybe just like meat and potatoes kind of thing.

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: So, you know, he spent a lot of time, you know, preparing meals and doing those sort of things. And obviously just chatting with the crew, learning more about the mission itself. And then once they got to the Lunar Receiving Lab here in Houston he helped do some work here and obviously he was in quarantine with the rest of the crew.

Host: Wow. So that must’ve been quite a long time then that he was in quarantine.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah they were in quarantine for a total of 21 days but that started from the minute that they left the lunar surface, a total of 21 days. So–

Host: Got it. Okay. Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah they wanted to be sure that, you know, they didn’t have any lunar bugs that they brought back just in case.

Host: I know. Yeah you go through all these different measures to make sure you’re not touching anything too much which I think blends in nicely with the next story.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah so Terry Slezak is a photographer who is in the Lunar Receiving Lab when the crew gets back. But before the crew actually left, he had been for a time trying to figure out how they were going to safe the film, you know make sure that they could process that film, make sure it wasn’t contaminated with lunar bugs. And so he’d been doing a lot of simulations in the Lunar Receiving Lab which is an awfully complicated process which I probably won’t go into because I’ll probably slaughter it. But you know they were trying different ways of making sure they could safely process the film but not release anything out into the public that wasn’t safe. And so, you know, they tried different ways of protecting the film. They put like nylon in between the film itself. Of course you couldn’t expose it to light, otherwise you would destroy the images. So they ended up using an autoclave trying to protect the film and interleaving it with a Kodak paper that they used. Well it worked fine for most of the simulations. And they would also introduce bacteria into some of the simulations because they wanted to make sure the autoclave was working and make sure that bacteria would be killed and he would try and grow bacteria on Petri dishes. Well things seemed to be working fine until like the day before they were going to bring back all that film and what happened is he got a phone call from his chief and said did you do something different to the film this time? And he said no, didn’t do anything differently. And it turns out all of the film in the canisters that he brought back over had melted in the bottom. So you know they were of course were very concerned because here we are, we’ve spent how many billions of dollars going to the moon and you know we might actually destroy this flight film. And we might not have a record of what happened on Apollo 11. So they had to go back and figure out what happened. They had to fix the autoclave. They had to replumb it and they had to do another simulation to make sure everything worked safely this time. And then of course they brought back the rock boxes. They brought back the photos. Well that’s photos– the film, the canisters. And so Terry Slezak is working with this film and he notices there’s a note from Buzz Aldrin that you know this is the most important magazine but Neil dropped it on the moon and he doesn’t think anything of it. He pulls it out and there’s all this black dust. And everyone around him is looking at him and he’s like whoa, what is that? And he’s like oh it’s lunar dust.

Host: Oh my God.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And everyone of course is kind of concerned because they’re like oh well, you know, that’s lunar dust and we’re just in plain clothes. So they take a picture of him. He’s got lunar dust. If you go on our website you can actually see it so–

Host: Oh cool.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: he holds that up. He becomes known as the first man to touch lunar dust. [laughs] But then there are protocols that have to be followed. He has to take a shower. He has to clean up with lots of Clorox. But in the meantime of course being a photographer and knowing about this historic moment, he is mainly concerned about the film. You know he’s not necessarily concerned about himself, but he’s concerned that this material is really going to be too rough on the film, it’s going to scratch it. And that we might lose the film anyways because of the lunar dust. So he’s very concerned about this. But Terry Slezak is an interesting guy. You know he’s in the lunar receiving lab, so in addition to taking care of the film he’s doing a lot of other tasks. He used to be an army medic so he’s taking the vitals of the crew like blood pressure and their temperatures and things like that. He’s also showing films in the crew reception area to the folks. They actually brought in some films so they could actually have some entertainment when they didn’t have anything else to do. But they were actually quite busy in there. He also was helping to safe the command module. The command module made its way back to the Lunar Receiving Lab and there were a lot of toxins in there that had to be removed. He said he went out to North American and learned how to safe the vehicle and learned a lot about the plumbing. And he was told look, I have enough to do because he was also in charge of taking photos inside the Lunar Receiving Lab. And they said oh you can just add it to your list, no big deal. He also helped clean out the command module and he said it was kind of a gross, yucky task. There were things in there that nobody would want to touch like used wash cloths, you know? When they would shave there’d be all these whiskers on there and things and they had to document everything that they took out and put it on a list. So, you know, he was quite busy. And he actually talks about what life was like in the Lunar Receiving Lab. He said it was just crazy, that people were constantly calling. They wanted to know, like what was going on. He said people would call at like 3 o’clock in the morning, hey you know we just want to know what’s going on in the Lunar Receiving Lab and he’s like I’m trying to sleep. [laughs] Like, what do you think is going on?

Host: He slept in the receiving lab?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. Yeah.

Host: Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: So.

Host: Random people or like managers and like–?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: He said it was their secretary.

Host: Okay.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: So, but you know I imagine that there were a lot of people, probably the news media as well–

Host: Oh yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: you know wanting the stories. And he was taking photos. He said he would post photos of what was happening in the Lunar Receiving Lab, you know, so people could come take photos of those photos. So, you know, there was a lot happening. There was a lot of attention on these guys and this building. Even though the mission was over.

Host: Right.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: Yeah. I guess mission– yeah the mission itself but maybe not the entirety of the mission. All the processing afterwards that happens especially the moon rocks and all. Every– all the scientists probably wanted them too. This Terry Slezak you said?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Mm-hmm. Yeah.

Host: A very interesting guy. Photographer. Former medic. Technician. Movie–

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: Like he made it into a movie theater. Janitor. He was cleaning stuff.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: [Laughs] right.

Host: Very interesting stuff, yeah. A man with many hats. Very, very cool. There’s an interesting story about the flag on Apollo 11. I think this is a very good one too.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. Yeah. So Jack Kinzler who we talked about who was our first oral history interview–

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: You know head of our– chief of tech services here at JSC. Well MSC at the time. You know he was called into a committee that Bob Gilruth had in his office and they were talking about, you know, what they might do to celebrate this lunar landing. Like how can we demonstrate– we did it. What can we do on the moon? And so the first thing that he suggested was well there needs to be a plaque. You know, something that demonstrates what happened. You know something where people can look and see, or another creature can look and see what we did. So he decided to go back and come up with some dummy plaques. And so he came up with the idea of a plaque with a flag on top of it, and sort of the astronaut’s name and then he presented that to Bob Gilruth and the rest of the committee and they said oh okay, you know, we’ll think about that. And they sent it up to headquarters. Headquarters worked on the wording and then they came back with– and I wanted to make sure I got it right so I brought. “Here men from the planet Earth”– excuse me, sorry my eyes – “set foot upon the moon July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.” Which interestingly enough I read in an interview with Tom Paine who said that originally they wanted to say we come in peace for mankind but the White House who also had a chance to review the plaque changed it to came. And they also decided to add the president’s name to the bottom because originally Jack Kinzler said they weren’t going to include the president because this was a NASA endeavor.

Host: Sure.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: It didn’t involve the White House. But they decided to go ahead and put Richard Nixon’s name on there.

Host: Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And you also notice on the plaque itself that there’s the two hemispheres. He said that Bob Gilruth was looking at the plaque and he saw the flag and he said you know it might be more interesting actually if you put the two hemispheres there because if there’s another creature that comes upon the moon, someday wants to figure out well where’s Earth, you know they’re not necessarily going to know where Earth is, but they could look and see this image and know oh that’s the planet. That’s where they came from.

Host: Ah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And so he said that’s where the idea originally came from. So the flag though was also something that Jack Kinzler was very interested in because he thought, you know, that would be a great way to mark the moment, to unfurl the flag on the moon. And you know you would think well that’s easy, we’ll just go down to Sears or Kmart and we’ll just buy a flag.

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And you actually couldn’t do that. So they had to come up with a flagpole and they had to come up with something that could be stowed on the lunar module and so they came up with this flag. It was the three foot by five foot flag that they came up with and decided how it was going to operate. They had to test it out. They also had to make sure it would fit on the lunar module so they went out to the lunar module that they have here and made sure it would all fit, they would be able to tuck it away safely. And then he had to go down and actually train the astronauts in how to deploy the flag on the moon. So he had to go down to the Kennedy Space Center and show Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin how this was all going to work. So they had to practice. And then he installed the flag on the lunar module along with the plaque before it went up to the moon. So you know a lot of people– you probably hear a lot of conspiracy stories about how of course we didn’t really go to the moon. A lot of people say well one reason is because if you look at that flag that’s on the moon, it looks like it’s fluttering in the wind. Well, Jack Kinzler had come up with this idea because of course they wanted you to be able to see the flag so they actually stitched a hem on this flag and they had an aluminum rod that would go through. You were actually supposed to completely stretch it out so it’d be completely straight for the photos. But the crew noticed that it would– if was kind of fluttering, you know the way it might flutter here on Earth and so they didn’t extend that aluminum rod that whole way. They decided to leave it where it looked like it was fluttering.

Host: Ah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And so to this day a lot of people say well of course it’s on a sound stage somewhere in Burbank or what have you, and but he had designed it that way.

Host: Wow. So it would’ve been– if they’d just pulled it out just all the way it would’ve been a completely stiff flag which was the design of it.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. Right. It would’ve been taught, yes.

Host: Yeah. Interesting. Yeah, that’s one of those things but it’s, yeah it’s just, they didn’t pull the rod out all the way.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right, yeah.

Host: Interesting.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: Wow. That’s cool. I like that. I don’t know if this is a true story so I don’t even know if I should tell it but it was just one of those things when because when I first started working here I started giving tours of the Apollo 11 Mission Control Room–

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Oh yeah.

Host: which is now being restored here on Friday. So or they’re going to open it up to the public on Friday. But one of the things we used to tell was that plaque that you were saying, I believe they made three of them if I’m not mistaken. The plaque that they actually put on the moon, they had a replica of it in that room and it was hanging on the wall underneath one of the flags that they brought to the moon which actually ended up being one of the Apollo 11 flags through some story that I won’t tell here. But it literally said the same exact thing that you just said, we came in peace for all mankind. And the story that we always used to tell was that there were three plaques made by three different contractors and every one of those contractors wanted to know– they were identical plaques– they wanted to know which plaque ended up on the moon so that contractor can say my plaque, and they, and I guess no one ever told them or no one ever knew which one was which so that way they can all share credit.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right.

Host: And I forget where that third one is. One’s here and the other one’s on the moon and I think the other one I want to say is in the Smithsonian so I can’t say for sure.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah I hadn’t heard that story before.

Host: Yeah. Yeah it was one of those things that we always used to tell. It was really cool. They had like little artifacts all around the moon and I think they’re going to bring them all back for the Apollo MOCR opening here soon.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Oh well that’s great.

Host: Yeah. But it was just one of those stories. I love that story. I think this is a great story to end it all off because we started with, you know, some shuttle astronauts recalling seeing the moon landing as a kid. We went even before the moon landing to say this is when shuttle started and we went all the way through but, you know, after the astronauts landed of course you know you were saying the whole world was celebrating. And so the astronauts went around the world to celebrate with them. And it was sort of this parade. So what was this thing? What was the, this I guess parade of astronauts going all around the world?

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah so there was a goodwill tour that the president sent the astronauts and their wives on. And so it was a tour of 22 countries in 38 days so it was sort of this whirlwind tour.

Host: Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And we have an interview with one of the secretaries who went with the crew and their wives. Geneva Barnes tells some interesting stories from that great, or “Giant leaps” tour and you know it was just an exhausting tour. You know they would spend a night at every location except for I think she mentioned Bankok and Rome. You know they were just constantly on the move. They had a plane. They were in the Vice President’s plane, Air Force Two which they considered really their home away from home. They had meals there. They could drink the water there. They could take naps. So it was really nice for them because they were constantly on the move. Everyone just wanted a piece of the astronauts. Everybody wanted to see them. Crowds were everywhere. You know the first place that they went, Mexico City, I mean if you’ve ever seen the photos, I mean it’s just amazing how close the crowds are to the Apollo 11 crew.

Host: Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And she talks about the fact that they were so busy– they were so jetlagged, they were constantly moving around. They weren’t, you know, as you and I do when we go on travel, we’re probably tired. We’re not eating well. We’re not sleeping well because we’re not in our own beds. And she said that a lot of the embassies, the state department embassies would talk to each other when they were coming, when they were scheduled to come, and they would talk about the fact that well, you know, there have been some illnesses on the crew, you know these– because they didn’t just come with the wives and the astronauts and Geneva Barnes, there were other people that came. And they were worried that well maybe you know that quarantine period wasn’t long enough because maybe the crew actually did bring back some sort of lunar germ because everyone’s been getting sick and some people had flu-like symptoms. And the physician that came with them, Dr. Carpentier who was also onboard the mobile quarantine facility and in the LRO–

Host: I remember the name, yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. So he had to actually go talk to the media when they were in London and explain, no the crew didn’t bring back any lunar bugs, you know? They were just tired. They were just, you know, they had a hectic schedule and they were just kind of worn out which I think is, you know, kind of amusing that people would actually be concerned about that. They had already gone through a quarantine.

Host: Yeah well it was, I mean this, we’ve brought up this idea of a lunar bug through so many different parts of this story. You could tell it was just something that was so prominent in the world.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Well you know it was a big fear.

Host: Sure.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: A big unknown at that point.

Host: An unknown, exactly.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. And we still would quarantine the crews, you know? And we still quarantined 12 and 14 just to be sure even though the Apollo 11 crew was fine. But she also tells a number of other interesting stories. She talks about for instance going to Belgrade. They met the deputy prime minister there and they invited the astronauts out for a duck shoot and they took their wives on a tour down the Danube River and they took them out for a seven course lunch and they said that they were so full. And that lasted until four or five in the afternoon and then they got word that well the chef’s back at the hotel they were staying at got a hold of the ducks and they were planning this huge dinner for them. So they were, you know, stuffed already from this huge meal.

Host: Right.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And they had to go back to the hotel and get ready for dinner and eat whatever the chefs had come up with using these ducks. They really only had one rest stop that she remembers. When they went to Rome she couldn’t remember if there was an American ambassador there at the embassy at the time but they gave them the afternoon there at the embassy. So they had a chance to just really relax and be themselves and play tennis. And she mentions that they ate hamburgers and hot dogs and potato salad. I mean how much more American can you get, right? [laughter]

Host: Probably much needed after this, you know– was that probably towards the middle of the tour too, just a break.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah I think they really needed it because there were so many crowds. She talks about going to Senegal for instance in Dakar. And she said the plane landed and these crowds just rushed toward the plane. They had to turn off the jets because they were just like here come all these people, you know just tons and tons of people. They finally managed to get them out and into cars and she said that was challenging as well because, you know, they were supposed to be following each other to the hotel but she said they’re– people managed to wedge their way in between the vehicles. She said it was so scary because at one point security came back and told them to get out of their vehicle because they were taking their car for the astronaut wives. And they said find another way– find another car– and she was like how are we going to find another car? They managed but she said they were all kind of squished on each other, sitting on each other’s laps. She said it was just so crazy. At one point the car that had the astronauts started to overheat and she said she doesn’t understand the mechanics but she said she’d heard that if you want to make sure your car doesn’t overheat, you turn on the heater and that sort of helps things.

Host: Oh.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And so she said they ended up taking a shortcut through a soccer field and made their way to the hotel which she said it was just a very scary moment because people were just, you know, they wanted to see these astronauts, hear these celebrities that came back from the moon. And they wanted a picture of them or just a glimpse of them.

Host: Everybody was going nuts. Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: They were. Yeah they had space fever, you know?

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: And when they went to Bombay in India, she said a lot of people from the embassy didn’t go out but they estimated there were about a million and a half people who were there just to see the astronauts.

Host: Wow. Huge country. Huge population.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: So, huge crowds. Yeah.

Host: Yeah huge crowd.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. And then she said when they went to the Congo which is a very different story from when they went to Senegal, she said that there was a lot, a lot more crowd control there because the president had put in place these police officers with whips. So if somebody tried to step out and go to the plane or get in front of an astronaut car or try and open the door a whip would come down on them and they’d scurry back to the sidewalk or the location that they were supposed to be at. Like kind of scary.

Host: Yeah.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: Imagine like seeing that.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah. She said that the place that they ended up staying was outside of town. It was near a private zoo that the president owned and you could actually hear the animals at night, the wild animals. So, you know there’s some interesting stories from there. Probably the other interesting story she told was when they went to Tehran they were actually able to see the jewels that the Shah had. And they were locked away behind glass and so they told them don’t touch the glass with your forehead or your hands. It’ll create a huge problem. Then of course somebody didn’t follow directions and so doors– alarms went off, doors started shutting. They managed to get everybody out in time but, you know, that was probably another scary moment.

Host: Wow.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: I mean these stories are incredible, the ones Geneva is telling. But I can just imagine trying to– because she’s the secretary, she’s part of the organization of this–

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yes.

Host: trying to come up with alternate routes if you’re getting broken up and now you have to deal with okay now the doors are closing on us and alarms are going off, what do we do? That had to be one of the most stressful like tours that you could possibly go on with that many people just so excited in every single place you go. And I think that’s one of the great things about this mission is how it captivated the whole world. I know– I think it’s in the book “Marketing the Moon”, I forget exactly the number so this might not be a good thing to quote but I’ll do it anyway, is I think 95% of the world’s televisions were tuned into the moon landing I believe. Everybody was. Now again this is a time when there was three channels but you know it’s, it was one of those things where everybody was tuned in. So naturally everyone would be excited and all the papers would say man landed on the moon. And it was for all of mankind too so everyone was engaging with it.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Right, yes.

Host: It was just a wonderful thing.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: I mean the United States accomplished this goal but I think the whole world saw it as an opportunity as Neil Armstrong said– a giant leap for mankind. He didn’t say it was a giant leap for the United States of America.

Host: Right.

Jennifer Ross-Nazzal: Yeah.

Host: Yeah. And that was intentional, right? They thought about that ahead of time.

[ Transition Sound ]

Host: Hope you really enjoyed these stories from Dr. Ross-Nazzal. It was some great stuff. And thanks for sticking around. We have a few more stories to tell but these will be told by the people who actually experienced them. At the beginning I mentioned we made a video at Rice Stadium very recently and had a chance to pull aside some alumni of the Apollo Program who had some interesting stories. So, here they are. I hope you enjoy. First is George Fletcher who actually experienced John F. Kennedy’s speech at Rice Stadium.

[ Transition Sound ]

George Fletcher: Okay I’m George Fletcher. I was about in the 7th grade when we were sitting in class and all of the sudden the teacher comes running into the classroom, everybody up, everybody up. And so we all got up. They hustled us out to the bus and we got on the bus and somewhere along the line we learned we were going to go listen to the president. Okay, fine. So we went out to Rice Stadium and they had us come off the bus, get into the stands, and we all sat prim and proper just like we’d always been taught and we listened to the president. Well I say we listened, I was in the 7th grade and so I wasn’t all that excited about what he had to say, at least not at that point in time, but we listened politely. And it was hot. It was very hot. And after it was over, we got back on the bus and had to go back to school. But it was a very exciting time because when I look back on it and see the importance of what he was saying at that time, and then for me to graduate from school and go to work in the space program, it means a lot more to me now that I was there. I appreciate being there.

Interviewer: So what did you in the space program? Tell me about your adult life?

George Fletcher: I worked– started out as a quality engineer but transitioned over to systems safety and I’ve been in systems safety for nearly 40 years.

Interviewer: So were you a NASA contractor or–?

George Fletcher: Contractor, yes.

Interviewer: Okay.

George Fletcher: And I started out, the last four days– I came to the center on the last four days of Skylab 4 and after that I went through the ASTP program, went through the complete shuttle program, did some with space station, and now I’m back doing Orion.

[ Transition Sound ]

Host: Here’s Don Whalen who actually worked on all the unmanned and manned missions of the Apollo Program.

[ Transition Sound ]

Interviewer: What was your technical expertise?

Don Whalen: The Environmental Control System. I worked on the– it’s called the ECS, the Environmental Control System on the command module for Apollo. And we, you know, worked on the design, development, test, certification, and mission readiness for the system.