Following a launch scrub a week earlier, space shuttle Columbia took to the skies on Nov. 12, 1981, for its second trip into space. Astronauts Joe H. Engle and Richard H. Truly rode the reusable, orbital, spacecraft on a pillar of fire from Launch Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Their planned five-day mission had to be curtailed to just two days following the failure of one of Columbia’s three fuel cells. Despite the shortened flight, Engle and Truly operated the first science payloads aboard a space shuttle and conducted the first tests of the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS). They brought Columbia safely home to a landing at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Facility, now NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Facility, at Edwards Air Force Base in California, where ground crews began to prepare the ship for its next mission to space.

Left: Official crew photo of the STS-2 crew of Joe H. Engle, left, and Richard H. Truly. Right: Official crew patch of the STS-2 mission.

Following the Nov. 4, 1981 scrub caused by problems with two of Columbia’s Auxiliary Power Units, engineers flushed the gear boxes and replaced filters in the units, and managers reset the launch for Nov. 12. Engle and Truly arrived back at KSC on Nov. 10. The next day, ground crews found a problem with a Multiplexer De-Multiplexer (MDM), a data management device aboard Columbia. A spare MDM also failed, so a unit from space shuttle Challenger, then under construction in Palmdale, California, was flown in and installed in Columbia. This delayed the launch by nearly three hours.

Left: STS-2 astronauts Richard H. Truly, left, and Joe H. Engle enjoying the traditional prelaunch breakfast, the room decorated in honor of Truly’s 44th birthday. Middle: Following breakfast, Truly, left, and Engle don their pressure suits, this room also decorated to celebrate Truly’s birthday. Right: Truly, left, and Engle in the White Room at Launch Pad 39A, also festooned with a birthday greeting.

The launch day coincided with Truly’s 44th birthday, and he became the first person ever to fly to space on his birthday. Ground crews helped him celebrate the occasion by decorating various rooms in KSC’s Operations and Checkout Building, and even the White Room at the launch pad, for the occasion as he and Engle prepared for the liftoff. Launch managers held the final countdown for a few minutes at T-minus nine minutes to clear up some minor technical issues before issuing a “Go” for launch.

Left: Liftoff of STS-2 as Columbia returns to space. Right: In Firing Room 1 of the Launch Control Center at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, engineers turn to watch the ascent of Columbia once the shuttle cleared the launch tower and control was handed over to the Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

At 10:10 a.m. EST on Nov. 12, 1981, exactly seven months after the launch of STS-1, Columbia’s main engines roared to life and the world’s first reusable, orbital, spacecraft lived up to its name. As soon as the shuttle cleared the launch tower, control handed over to the Mission Control Center (MCC) at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston. The Silver Team of flight controllers led by ascent Flight Director Neil B. Hutchinson monitored Columbia’s launch, with capsule communicator (capcom) astronaut Daniel C. Brandenstein relaying milestone events to Engle and Truly aboard the shuttle. Nine minutes after liftoff, Columbia’s main engines cut off and the large external tankjettisoned away from the spacecraft. The space shuttle had reached space but was not yet in orbit, that job left for Columbia’s Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines to complete. The next major task involved opening the orbiter’s payload bay doors to allow the radiators mounted inside them to cool the vehicle. Mission Control gave Engle and Truly a go to stay in orbit. They could now remove their launch and entry pressure suits and change into more comfortable flight suits.

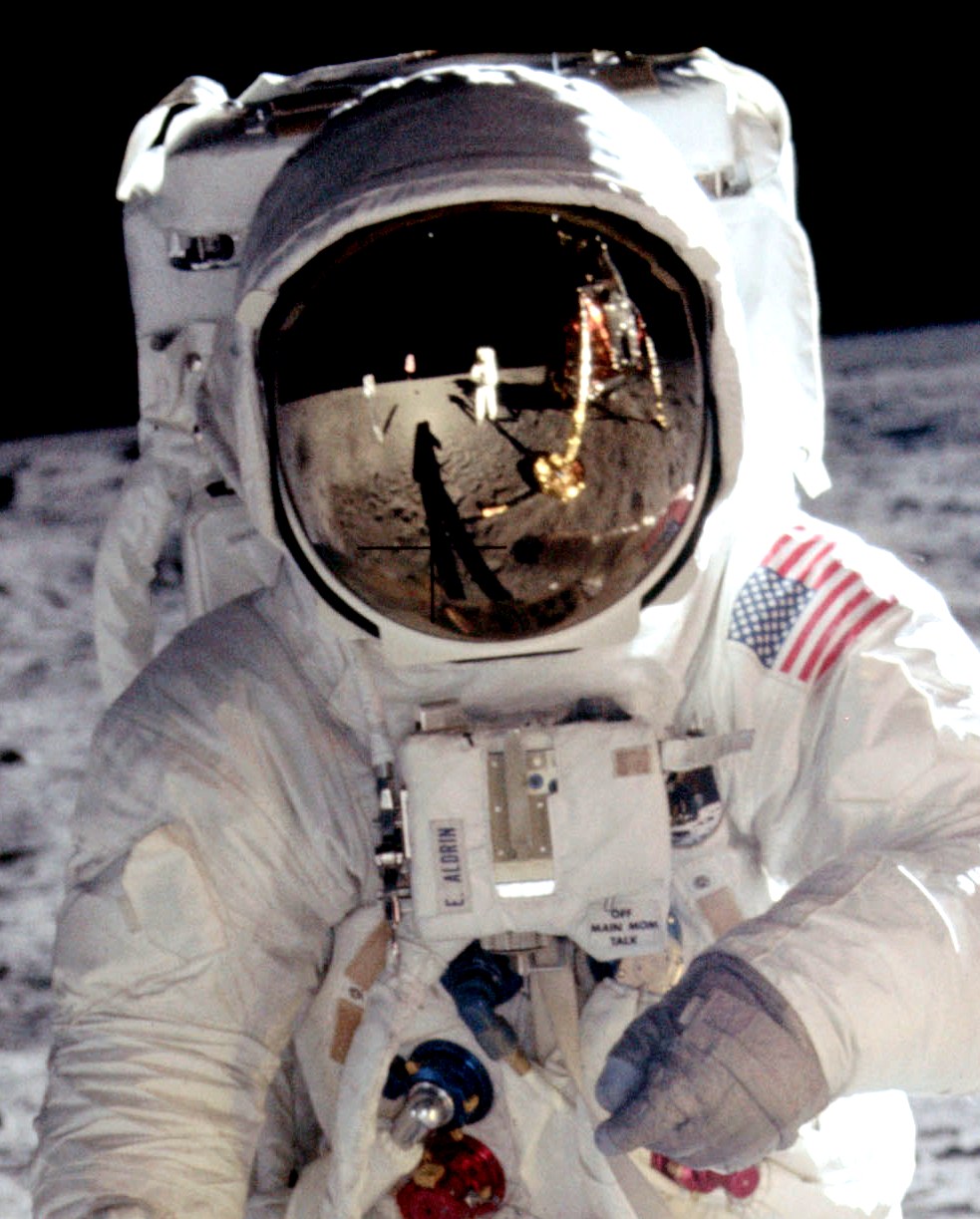

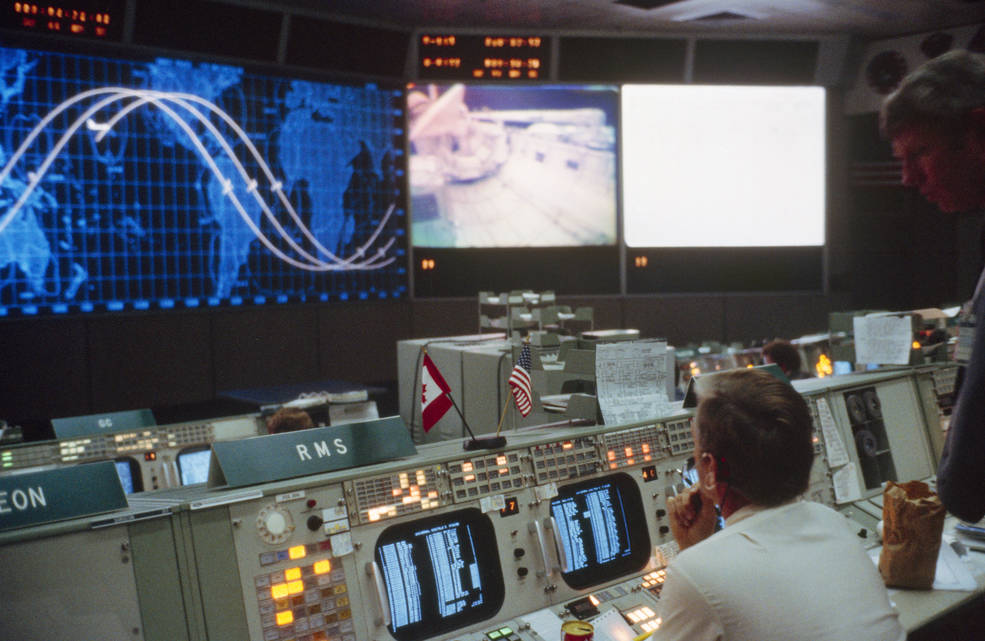

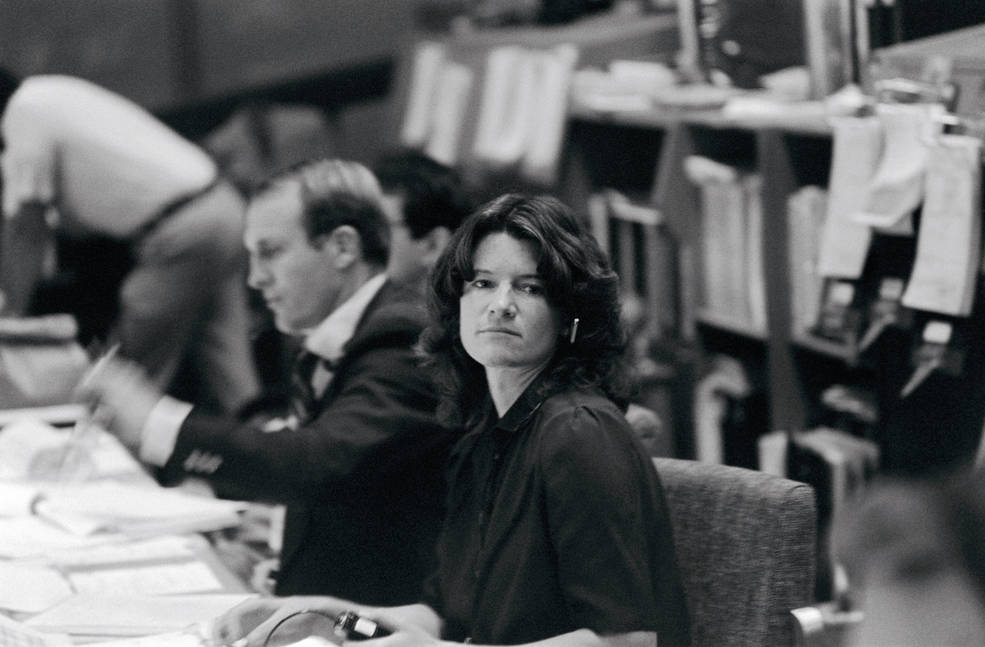

Left: The Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston during the STS-2 mission. Right: Capsule communicators (capcoms) James F. Buchli, left, and Sally K. Ride, the first woman to serve in that position.

About five hours into the mission, one of Columbia’s three power-generating fuel cells began to act erratically and capcom Brandenstein instructed Engle and Truly to shut it off. Flight rules stated that with only two working fuel cells, only a so-called minimum mission was permissible, meaning that instead of five days in orbit, Engle and Truly would have to bring Columbia home after 54 hours. Many high-priority activities moved up to be completed during the mission’s two days. Engle and Truly conducted two OMS tests, one to shut it down and start it up again four minutes later. Then they deactivated the faulty fuel cell, taking it permanently offline. Flight Director Donald R. Puddy’s Crimson Team of controllers took over the consoles in Mission Control, with astronaut Frederick H. “Rick” Hauck serving as capcom. Shortly before Engle and Truly went to bed for their first sleep period in space, Mission Control played a taped birthday greeting sung by the high school chorus in Forest, Mississippi, the hometown of Truly’s father and stepmother. Truly replied to capcom Hauck, “That’s beautiful. Please thank them and tell them I couldn’t have had a nicer birthday than this one. Appreciate it.” Engle and Truly then went to sleep in their seats on the flight deck. The OSTA-1 payloads in the payload bay, activated earlier in the day, continued to gather data overnight.

Left: The OSTA-1 payload in Columbia’s cargo bay. Middle: First use of the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS). Right: The RMS deployed over Columbia’s payload bay.

While the crew slept, in Mission Control the Bronze Team led by Flight Director Charles R. “Chuck” Lewis took over the consoles, with astronauts James F. Buchli and Sally K. Ride serving as capcoms. Ride became the first woman to serve in the role of capcom. Mission Control began the crew’s day by playing “Pigs in Space” as a wake-up call, a comedy routine by The Muppets arranged by Ride. First-time space flyers Engle and Truly reported they had a comfortable first night’s sleep aboard Columbia, telling capcoms Buchli and Ride, “we did get plenty of sleep last night, but it’s hard to sleep with all the opportunities to watch things.” Their first task of the day involved activating the RMS for its first in-orbit workout. With Truly controlling the 50-foot-long arm from Columbia’s aft flight deck, he deployed and stowed it again as an initial test, reporting, “It’s running very smoothly.” Truly then unstowed the arm, with TV cameras in the payload bay and on the arm’s wrist and elbow joints providing flight controllers with a great view of its movements. During the testing, Ride informed the crew that mission managers had made the final decision that due to the fuel cell problem, the flight would be the 54-hour minimum mission. After both Truly and Engle had a chance to operate the arm, Truly guided it back into its cradle, its first inflight testing a success. Flight Director Hutchinson and his team resumed their console positions, with astronaut Terry J. “TJ” Hart now serving as capcom.

Left: During a visit to the Mission Control Center (MCC) at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, President Ronald W. Reagan, left, listens as JSC Director Christopher C. Kraft describes the functions of the MCC. Right: President Reagan talks to the STS-2 crew of Joe H. Engle and Richard H. Truly during the mission’s second day.

President Ronald W. Reagan became the first sitting Chief Executive to step onto the floor of the MCC during an actual mission when he visited JSC on Nov. 13, 1981, the crew’s second day aboard Columbia. Accompanied by NASA Administrator James M. Beggs, the President received a tour of the MCC provided by JSC Director Christopher C. Kraft, the man responsible for developing the concept of mission control. President Reagan chatted with Engle and Truly for a few minutes, jokingly asking them if they could stop by Washington, D.C., and pick him up on their way to California. The President added, “I’m sure you know how proud everyone down here is and how … America has got its eyes and its heart on you.” Following his chat with the astronauts, he spoke a few words with their wives, Mary Catherine Engle and Cody Truly, before leaving the MCC.

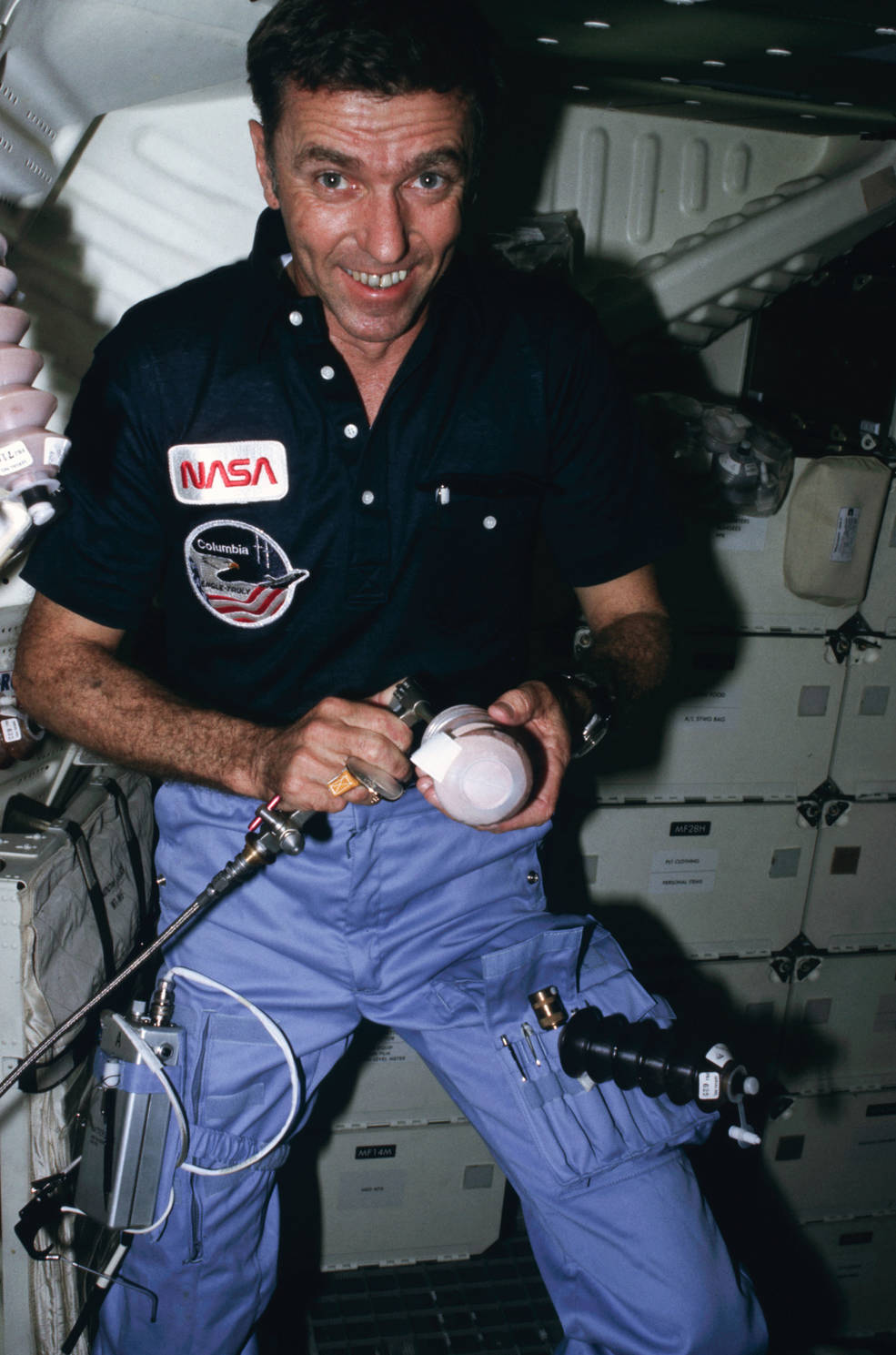

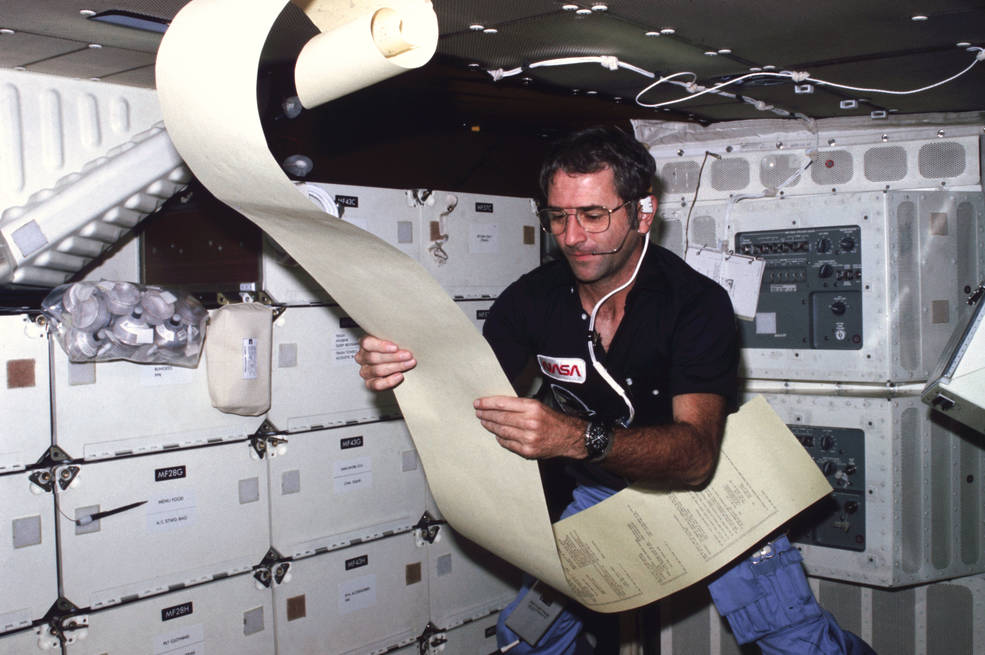

Left: Astronaut Joe H. Engle preparing tea in Columbia’s middeck. Right: Astronaut Richard H. Truly reads a printout of the day’s activities in Columbia’s middeck.

For the remainder of the day, Engle and Truly conducted additional evaluations of the orbiter, such as tests of the Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters, and took photographs of the Earth below. Engle also replaced a failed cathode ray tube (CRT) display on the flight deck. The OSTA-1 payload experiments continued to gather data. After the successful CRT repair, Engle jokingly requested that he be allowed to go and fix the failed fuel cell as well, to allow a full-duration mission. Mission Control politely ignored his offer. After a very busy day, Engle and Truly settled down for their last night’s sleep in space. In MCC, Flight Director Lewis’ Bronze Team, with astronaut Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield joining Buchli as capcom, replaced Hutchinson’s Silver Team on console.

Three views of Earth taken by the STS-2 astronauts – the Island of Cyprus in the Mediterranean Sea, left, the Strait of Hormuz, and Tokyo, Japan.

The crew’s landing day wake up music began with a rendition of “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,” performed by the Flight Operations Directorate group “Contraband,” followed by the second part of The Muppets’ “Pigs in Space” comedy routine. Flight Director Puddy’s Crimson Team of controllers, including capcoms Hauck and Steven R. Nagel, took their console positions to guide Engle and Truly through the reentry and landing of Columbia at what is now NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Early on entry day, Engle deactivated the OSTA-1 payloads in preparation for landing. They closed the payload bay doors, donned their pressure suits, maneuvered Columbia so it was flying tail first, and fired its OMS engines over the Indian Ocean for nearly three minutes to drop it out of orbit. Twenty-seven minutes later, Columbia encountered the first tendrils of the Earth’s upper atmosphere at an altitude of 400,000 feet. The heat of reentry caused a sheath of ionized plasma to form around the vehicle, blocking communications for 16 minutes.

Left: View of Columbia during final approach to NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center, now NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center, in California, taken by astronaut Kathryn D. Sullivan from a T-38 Talon chase plane. Middle: Columbia touches down on the dry lakebed runway. Right: Columbia on its final rollout.

Engle, together with the spacecraft’s computer, guided Columbia through a series of aerodynamic maneuvers in the hypersonic and supersonic phases of the entry to obtain information about the vehicle’s handling characteristics. Engle reported that the “maneuvers have been going very good [sic]. The bird is real solid.” Engle manually guided Columbia through a sweeping turn called the Heading Alignment Circle to line up with Dryden’s Runway 23. At about 400 feet, Truly lowered the landing gear and a few seconds later, Columbia’s main gear touched down on the dry lakebed runway, kicking up a cloud of dust. As Columbia continued to roll down the runway, Engle lowered the spacecraft’s nose, applied gentle brakes, and brought the vehicle to a stop after a 7,000-foot rollout. The STS-2 mission ended after 54 hours, 13 minutes. An estimated 200,000 people were on hand to watch Columbia’s second landing.

View of Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston after the landing of Columbia, ending the STS-2 mission.

Flight controllers in Mission Control in Houston erupted in cheers following Columbia’s successful landing. Capcom Nagel helped Engle and Truly deactivate the vehicle’s systems as ground crews at Dryden arrived on the runway to safe it from hazardous materials so the crew could exit the spacecraft.

Left: Astronauts Joe H. Engle, left, and Richard H. Truly disembark from Columbia following the conclusion of the STS-2 mission. Middle: George W.S. Abbey, Director of Flight Crew Operations at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, right, greets Truly and Engle. Right: Engle, left, and Truly during the postlanding walkaround, accompanied by Abbey.

After being instructed that it was safe to exit the vehicle, Truly and Engle climbed out of Columbia and bounded down the stairs of the access vehicle. Director of Flight Crew Operations at JSC George W.S. Abbey greeted them at the bottom of the stairs and the trio conducted a walkaround inspection of Columbia, finding it in remarkably good condition. Ground teams drove Engle and Truly to Dryden facilities where they changed out of their pressure suits and boarded a jet for the trip back to Houston.

Left: Joe H. Engle, left, and Richard H. Truly and their families are greeted by well-wishers after their arrival at Ellington Air Force Base in Houston, as Christopher C. Kraft, director of NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) addresses the crowd. Right: The morning after returning from space, Engle, left, and Truly, right, enjoy breakfast with Vice President George H.W. Bush at JSC.

Hundreds of well-wishers greeted Engle and Truly when they arrived at Ellington Air Force Base near JSC. Reunited with their families, they returned to their homes for their first night’s sleep back on Earth. The next morning, they had breakfast with Vice President George H.W. Bush, who was visiting JSC – the first back-to-back visits to JSC of the nation’s top two executives. The STS-1 crew of John W. Young and Robert L. Crippen also attended the breakfast with the Vice President.

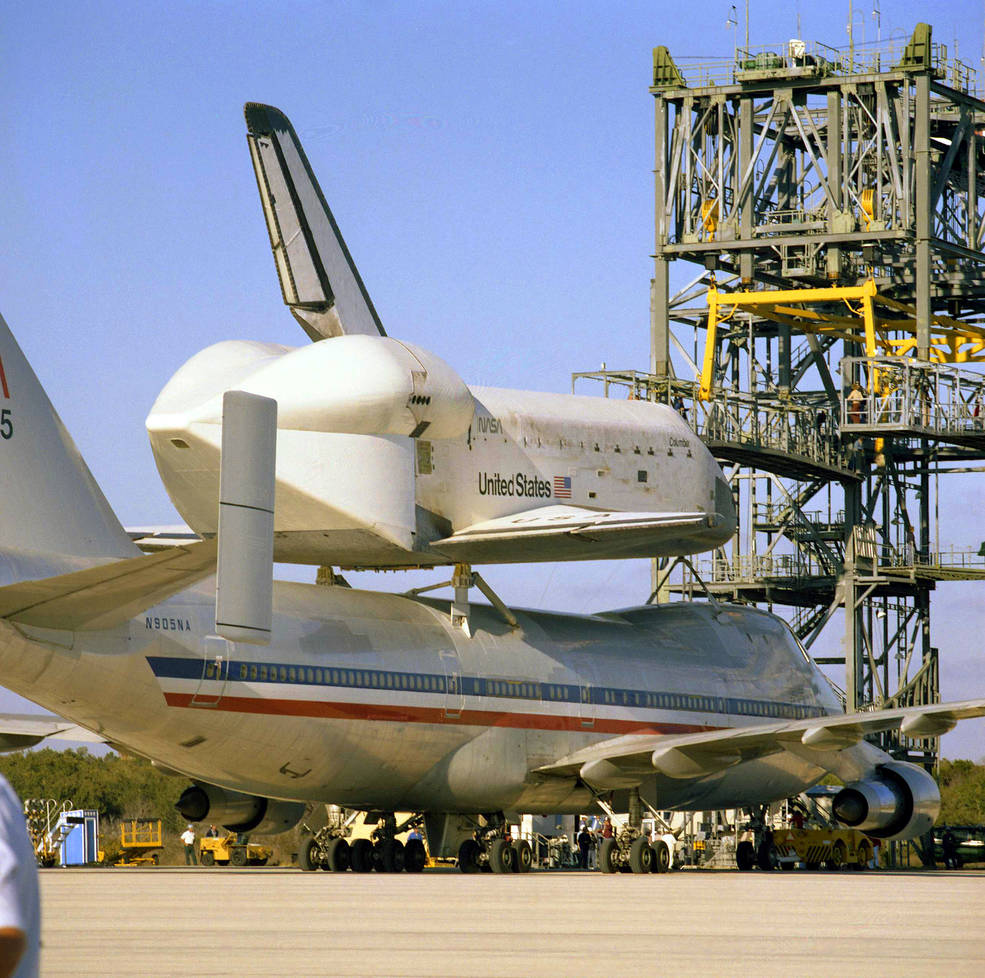

Left: Riding atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), space shuttle Columbia departs from NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center, now NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in California, for its cross-country trip to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Middle: Columbia, atop its SCA, arrives at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility. Right: Ground crews tow the SCA into the mate-demate device to lift Columbia from the back of the aircraft.

Ground crews at Dryden towed Columbia from the runway to a service area to begin preparing it for its cross-country trip back to KSC. After workers mounted it atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, a modified Boeing-747, Columbia left Dryden and arrived at KSC on Nov. 25, just 11 days after its landing in California. Workers towed it to the Orbiter Processing Facility to start preparing it for its next mission, STS-3, planned for March 1982.