Following the first launch attempt, halted by a computer glitch, STS-1 astronauts Commander John W. Young and Pilot Robert L. Crippen lifted off on April 12, 1981, aboard space shuttle Columbia, ushering in a new era of reusable spacecraft. Their launch came exactly 20 years after Soviet cosmonaut Yuri A. Gagarin’s inaugural human spaceflight. During the two-day test flight, Young and Crippen successfully tested the spacecraft’s systems, encountering very few problems and accomplishing all planned mission objectives.

Left: Official crew photo of the STS-1 crew of John W. Young, left, and Robert L. Crippen.

Right: Official crew patch of the STS-1 mission.

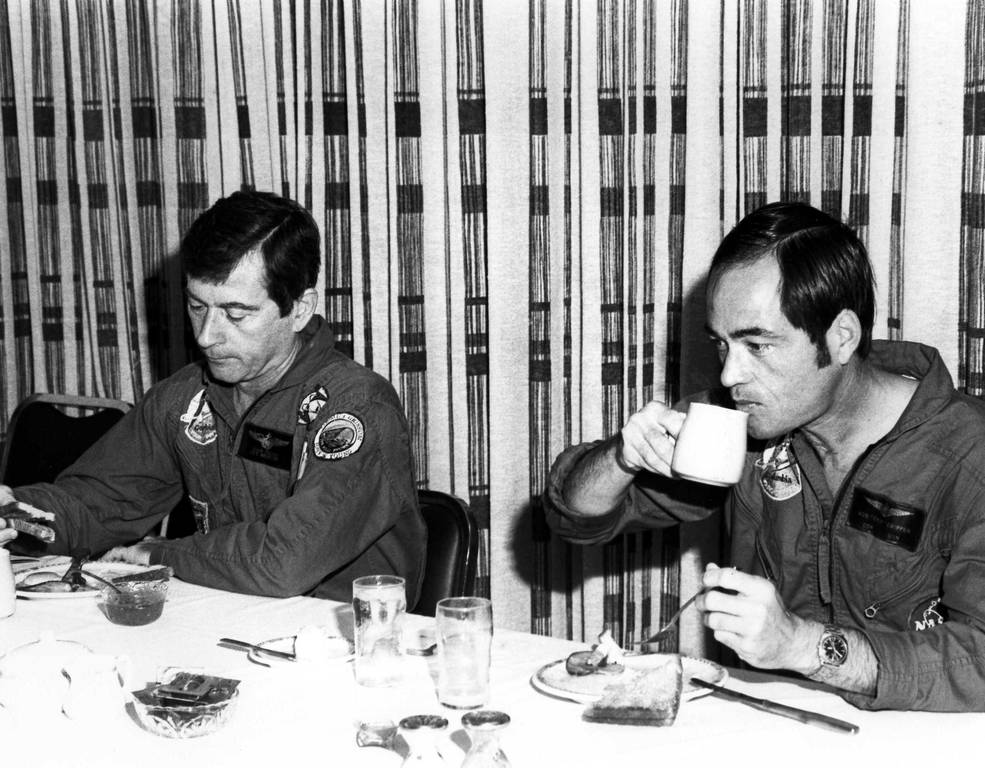

Following the April 10 scrub, engineers corrected the computer timing error, and controllers in the Launch Control Center’s (LCC) Firing Room 1 at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) recycled the countdown for another launch attempt on April 12. The countdown proceeded smoothly, and engineers refilled the large external tank with super cold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. Repeating the activities of two days earlier, launch test director Norman Carlson instructed personnel in the crew quarters in KSC’s Operations and Checkout (O&C) Building to awaken Young and Crippen. Following a brief physical examination, they ate their traditional breakfast with fellow astronauts and managers. Assisted by technicians, they donned their pressure suits and walked out of the O&C Building to the waiting astronaut van for the 15-minute ride to Launch Pad 39A. Young and Crippen arrived at the pad about two and a half hours before the scheduled liftoff, took the elevator to the crew access arm level, and entered the White Room, where technicians assisted them into Columbia. Support astronaut Loren J. Shriver, inside the orbiter to ensure all the control switches were in the correct settings, helped Young and Crippen into their seats in the cockpit.

Left: STS-1 astronauts John W. Young, left, and Robert L. Crippen enjoying the traditional prelaunch breakfast on the morning of April 12, 1981 – the day of the second launch attempt. Middle: Following breakfast, Young, left, and Crippen walk down the hall to don their pressure suits. Right: Crippen, left, and Young donning their pressure suits prior to launch.

Left: STS-1 astronauts John W. Young, front, and Robert L. Crippen leaving the Operations and Checkout Building for the ride to Launch Pad 39A. Middle: Space shuttle Columbia awaits its crew at Launch Pad 39A. Right: Technicians in the White Room at the end of the crew access arm assist Crippen, left, and

Young to board Columbia.

The countdown resumed after the planned hold at the T-minus 20-minute mark, and this time Columbia’s four primary and single backup computers synchronized as planned. During another planned hold at T-minus 9 minutes, Launch Director George F. Page read a message from President Ronald W. Reagan to the STS-1 crew. President Reagan’s message began, “You go forward this morning in a daring enterprise and you take the hopes and prayers of all Americans with you,” and continued to wish the crew a successful launch, mission, and a safe return to Earth. Page added his own words, speaking for the entire launch team, “We wish you an awful lot of luck. We are with you one thousand percent and we are awful proud to have been a part of it.”

Left: View inside Firing Room 1 of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Control Center during the STS-1 countdown. Right: Launch Director George F. Page reads a statement from President Ronald W. Reagan to the STS-1 crew shortly before launch, as KSC Director Richard G. “Dick” Smith, left, and Robert Reed, orbiter project engineer, listen.

In the KSC viewing stands, hundreds of spectators and news media personnel gathered for the historic launch of Columbia. Among them, former astronauts, NASA managers, and members of Congress. Elsewhere at KSC and on nearby beaches, an estimated 600,000 people gathered to see the first space shuttle take to the skies, undeterred by the launch scrub two days earlier.

In the viewing stands at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida to experience the STS-1 launch. Left: Apollo 11 astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, left, chatting with former KSC Director Lee R. Scherer. Middle left: Apollo 11 astronaut Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin. Middle right: Apollo 9 astronaut Russell L. “Rusty” Schweickart. Right: Congressmen C. William “Bill” Nelson, left, whose district included KSC and today is NASA’s administrator nominee, and J. Donald “Don” Fuqua, chairman of the House Science and Technology Committee.

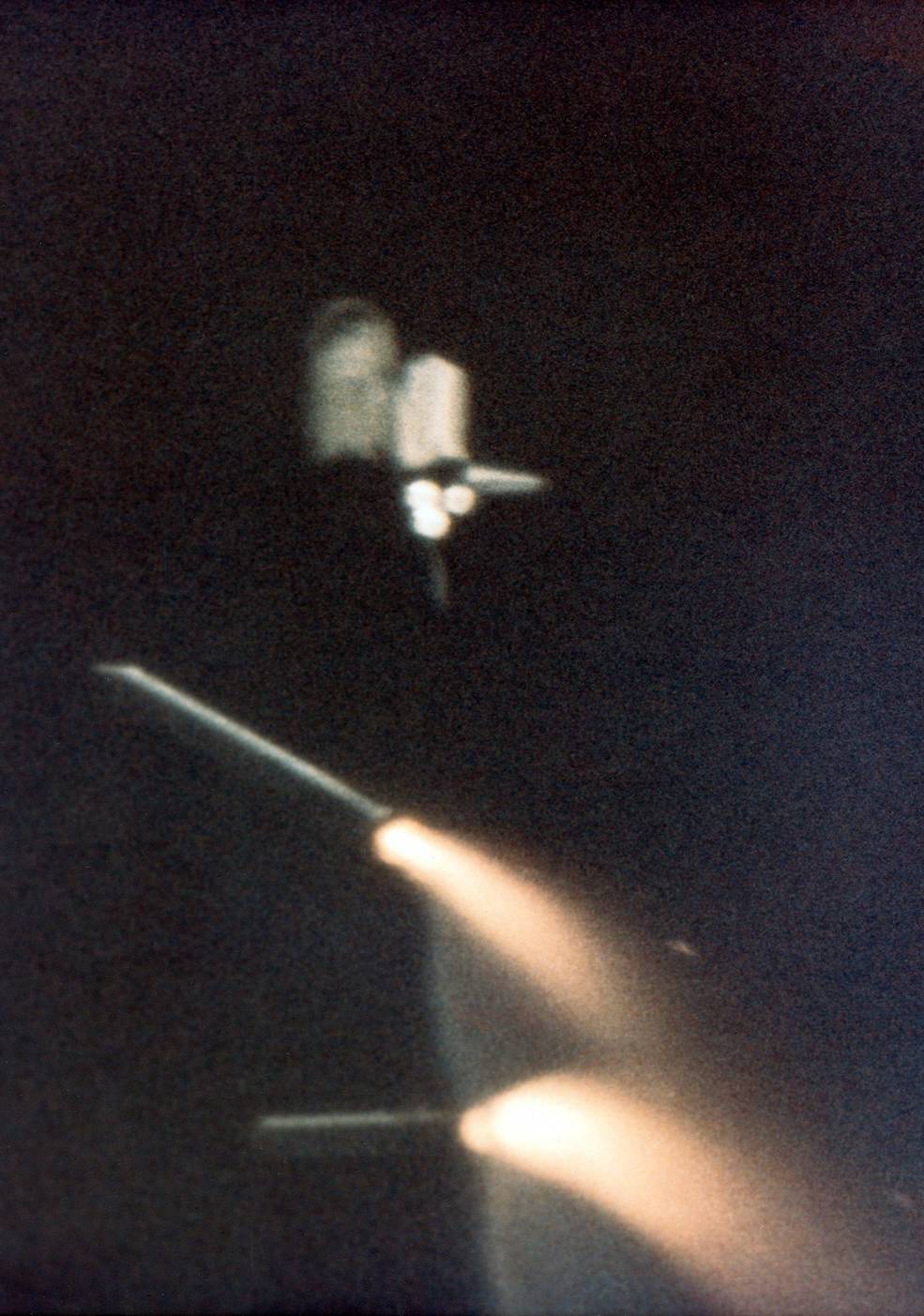

At precisely 7 a.m. ET on April 12, 1981, starting at T-minus 3.8 seconds, space shuttle Columbia’s three main engines ignited within 120 milliseconds of each other followed at T-0 by the ignition of the two side-mounted solid rocket boosters (SRBs). The combined engines generated 6.8 million pounds of thrust, lifting the 4.5-million-pound vehicle off Launch Pad 39A.

Liftoff of space shuttle Columbia on the STS-1 mission.

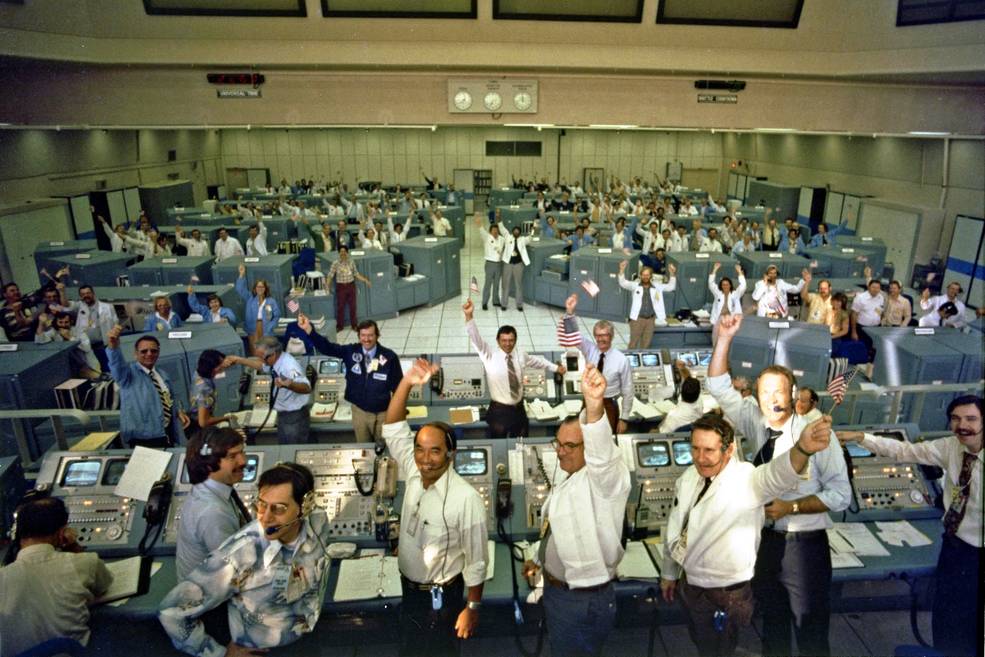

Within six seconds, the shuttle cleared the launch tower and control of the mission shifted from KSC’s LCC to the Mission Control Center (MCC) at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. The Silver Team of flight controllers led by ascent Flight Director Neil B. Hutchinson monitored Columbia’s launch, with capsule communicator (capcom) astronaut Daniel C. Brandenstein relaying milestone events to Young and Crippen aboard the shuttle. Due to greater-than-expected performance of the SRBs, Columbia initially flew at a slightly higher altitude than originally planned. At 2 minutes, 12 seconds into the ascent, the two SRBs completed their job of helping loft Columbia off the ground. They separated from the vehicle and splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean. Crews aboard two recovery ships later retrieved the SRBs and towed them back to port for refurbishment and reuse on later shuttle missions. The shuttle relied on its three main engines to complete the ride to orbit, with the external tank providing the fuel and oxidizer. Eight and a half minutes after liftoff, at an altitude of 73.6 miles, the main engines cut off as planned and the shuttle jettisoned the external tank that later burned up on reentry. Columbia was in space, although not in its final orbit yet. To accomplish that, it completed two burns of its orbital maneuvering system (OMS) engines, the first lasting about 90 seconds after external tank separation, and the second taking place 34 minutes after the first, placing Columbia in a 150-mile circular orbit around the Earth.

Left: Space shuttle Columbia clears the launch tower. Middle left: Leaving behind a long plume, Columbia continues to climb. Middle right: Long-range camera view of the separation of the two solid rocket boosters. Right: The external tank following separation.

Left: Controllers in Firing Room 1 of NASA’s Kennedy Space Center’s (KSC) Launch Control Center cheer after the successful launch of space shuttle Columbia. Right: Spectators in the KSC viewing stands watch the launch of space shuttle Columbia.

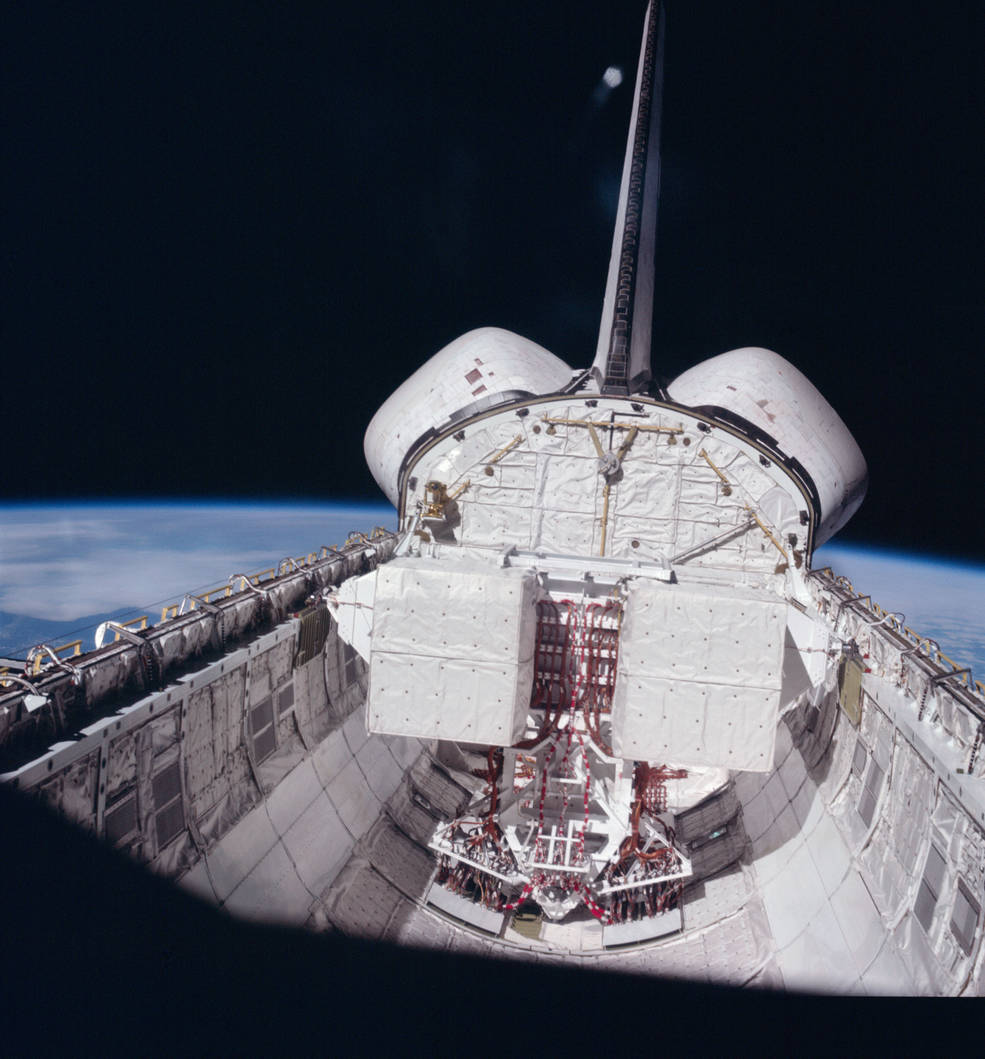

Young and Crippen settled in to begin their on-orbit activities. One of their first tasks involved opening the shuttle’s two large payload bay doors, required to ensure the radiators attached to them could regulate the vehicle’s temperature. Since this marked the first time the astronauts opened the large doors in space, they followed a slow, methodical process, first opening the starboard door and closing it back up to make sure the vibrations of launch and the effects of weightlessness did not alter its shape. They next opened the port door and followed the same process before finally opening both doors and deploying the radiators. As the shuttle flew over the United States on its first revolution around the Earth, Young and Crippen downlinked television images of the payload bay to the MCC in Houston.

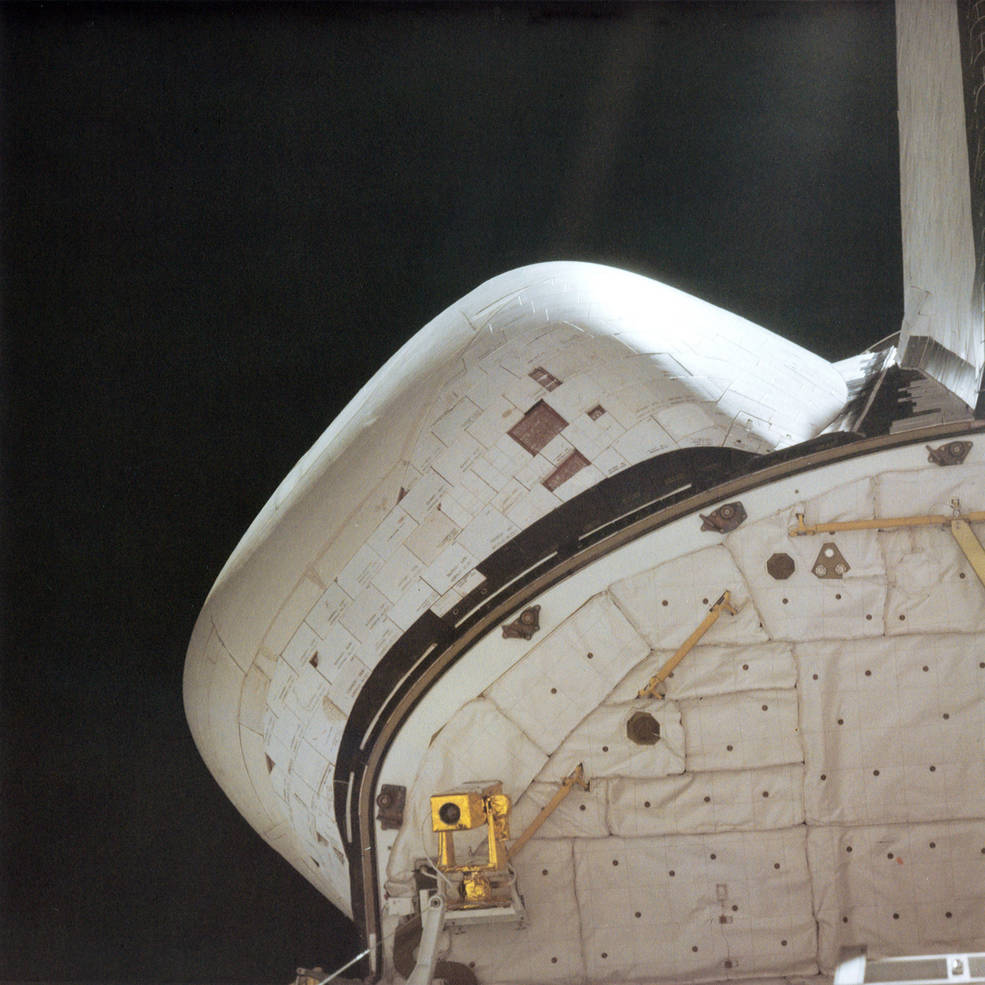

Left: View of space shuttle Columbia’s payload bay, showing the two white boxes of the Development Flight Instrumentation, and the two Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) pods with areas of missing and damaged thermal protection system tiles. Middle: Close-up view of the starboard OMS pod showing details of the missing and damaged tiles. Right: View of the port side radiator mounted on the payload bay door.

In addition to reporting that all went well with the payload bay door operations, Young and Crippen also radioed down to MCC that they noticed several areas on the OMS pods that appeared to be missing some of the thermal protection system heat-resistant tiles. Controllers in MCC saw these areas on the televised images. After a detailed analysis, engineers determined that 11 tiles were damaged or missing from the starboard OMS pod and between four and six from the port OMS pod. The largest single damaged area measured about eight inches by eight inches. The engineers concluded that the damage did not constitute a risk to reentry as it occurred in areas the did not see the highest temperatures. Additional analysis revealed that no tiles were missing from the underside of the orbiter, the area of the vehicle that sees the highest temperatures during the reentry. Another minor issue that continued to be a nuisance throughout the flight was that one of the Development Flight Instrumentation (DFI) recorders that monitored various vehicle parameters refused to turn off on command, causing concern that it would run out of tape prior to reentry when it was most needed. The crew solved the problem by cycling the circuit breaker that fed power to the unit as needed.

View of the Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston during the STS-1 mission’s first day in space, as controllers assess the televised images of the missing and damaged tiles on Columbia’s orbital maneuvering system pods.

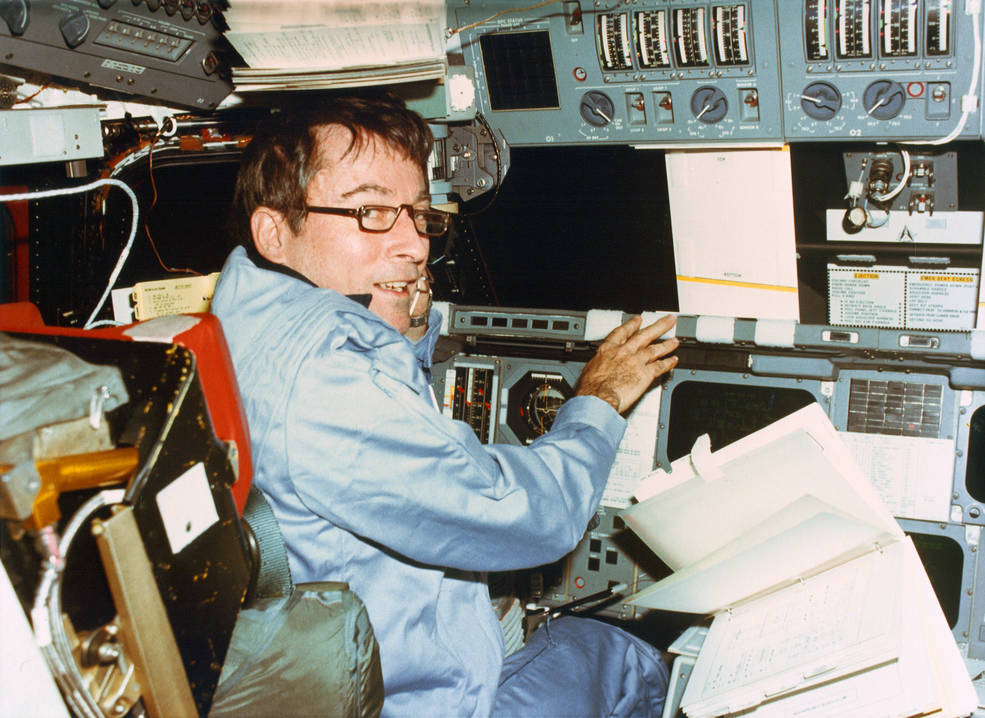

At the end of Columbia’s second revolution, capcom Brandenstein informed Young and Crippen that, after assessing the condition of all shuttle systems, managers had given them a “go” to continue with on-orbit operations and they could remove their pressure suits, changing into more comfortable, lightweight flight suits. In the MCC, Flight Director Charles R. “Chuck” Lewis and his Bronze Team of controllers replaced Hutchinson’s Silver Team, with astronaut Henry W. “Hank” Hartsfield replacing Brandenstein as capcom. Young and Crippen ate their first meal aboard the shuttle before resuming their work that included two more OMS burns, first using only the right engine and the second using only the left. This placed Columbia into a 170-mile-high near-circular orbit compared to its previous 150-mile orbit. They also successfully tested the orbiter’s flight control surfaces and reaction control system (RCS) thrusters. During a television broadcast from the shuttle’s flight deck, Young and Crippen paid tribute to John Bjornstad and Forrest Cole, two technicians who died during a launch pad accident following the March 19, 1981 countdown demonstration test, saying, “They believed in the space program, and it meant a lot to them. I am sure they would be thrilled to see where we have the vehicle now.” A third technician, Nicholas “Nick” Mullon, died in 1995 from long-term complications from the accident. After a grueling 13-hour first day in space, Young and Crippen began their first sleep period aboard Columbia, sleeping in their seats on the flight deck. Capcom Hartsfield said goodnight with a “super ATTA BOY” for their tremendous accomplishment. Flight Director Hutchinson and his Silver Team of controllers returned to their consoles to monitor the shuttle while the crew slept.

Left: STS-1 Commander John W. Young during a test of space shuttle Columbia’s reaction control system thrusters. Right: STS-1 Pilot Robert L. Crippen enjoying weightlessness on his first flight in space.

Although Young and Crippen awoke before the first communication session, MCC kicked off their second day in space with a wake-up song called “Blast-Off Columbia,” specially written for the occasion by shuttle technician Jerry W. Rucker and sung by Roy McCall. Two hours later, after the crew ate their first breakfast in space, Flight Director Donald R. Puddy’s Crimson Team of flight controllers, with astronaut Joseph P. Allen serving as capcom, relieved the overnight Silver Team. While passing over the Orroral Valley, Australia, ground station, Crippen played a bit of the iconic Australian ballad “Waltzing Matilda,” sung by Australian country singer Slim Dusty, for the controllers Down Under, much to their delight. The crew completed additional tests of Columbia’s flight control surfaces and RCS thrusters, televising some of the events. For lunch, they enjoyed hot corned beef sandwiches, according to Crippen, “courtesy of John Young,” an allusion to Young having smuggled such a sandwich aboard his Gemini 3 mission in 1965, prompting capcom Allen to comment, “Oh my! Oh my!” During free moments, Young and Crippen enjoyed the view of the Earth below them, capturing the scenery with stunning photographs.

Three views of Earth taken by the STS-1 astronauts – Cape Cod, Massachusetts, left, the San Francisco Bay area, and southern Baja California, Mexico.

During their 21st revolution, while flying over the United States, Young and Crippen received a telephone call from Vice President George H.W. Bush at the White House, standing in for President Reagan, still recuperating from an assassination attempt two weeks earlier. During the televised event, echoing the President’s pre-liftoff words to the crew, Vice President Bush told Young and Crippen,“your trip is going to ignite the excitement and the forward thinking for the country.” Bush wished them well on the rest of their mission, adding, “We’ll be watching that re-entry and the landing with great interest on behalf of the whole country.”

Left: Still image from television downlink of STS-1 astronauts John W. Young, left, and Robert L. Crippen speaking with Vice President George H.W. Bush, inset. Right: Still image from television downlink of Crippen replacing carbon dioxide-absorbing lithium hydroxide canisters in Columbia’s middeck.

In the MCC, Flight Director Lewis’ Bronze Team resumed their console positions to support Young and Crippen through the remainder of their second day in space. Aboard Columbia, the astronauts practiced putting on their pressure suits, finding the activity not too difficult in weightlessness, a rehearsal for the next day’s reentry and landing. They also closed and reopened the payload bay doors, also in preparation for the return to Earth the following day. Crippen attempted to replace the malfunctioning DFI recorder but could not undo several screws – later investigation revealed that a technician had treated them with Loctite. A television broadcast showed him replacing carbon dioxide-absorbing lithium hydroxide canisters. For the crew’s dinner musical entertainment, MCC played a version of “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.” With all shuttle systems performing as expected, Young and Crippen retired for their second and final sleep period in space. In the MCC, the Silver Team once again took their consoles for the overnight shift, relieving the Bronze Team.

To be continued…