The year 1986 was shaping up to be the most ambitious one yet for NASA’s Space Shuttle Program. The agency’s plans called for up to 15 missions, including the first flight from the West Coast launch site at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Other important missions included the launch of two planetary spacecraft with very tight launch windows, an astronomy mission to study Halley’s Comet, and the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope. The first mission of 1986, STS-61C, delayed from December 1985, flew between Jan. 12 and 18. The next flight, designated STS-51L, marked the 25th in the program and the 10th for space shuttle Challenger. During the six-day mission, the seven-member crew was to deploy a large communications satellite, deploy and retrieve an astronomy payload to study Halley’s Comet, and the first teacher in space would conduct lessons for schoolchildren from orbit.

Left: STS-51L crew members Michael J. Smith, front row left, Francis R. “Dick” Scobee, Ronald E. McNair; Ellison S. Onizuka, back row left, S. Christa McAuliffe, Gregory B. Jarvis, and Judith A. Resnik. Right: The STS-51L crew patch, with the red apple symbolizing McAuliffe’s Teacher in Space program.

The primary objective of the STS-51L mission was to launch the second Tracking and Data Relay System (TDRS) satellite into orbit, part of a network of satellites in geostationary Earth orbit that, once completed, allowed near-continuous communications during shuttle missions. Designated TDRS-B, the large communications satellite relied on a two-stage solid-fuel Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) to reach its final orbital position after deployment from the space shuttle on the mission’s first day. Observation of Halley’s Comet, making its return to the inner solar system in its 76-year orbit around the Sun, was the objective of the Spartan-Halley astronomy satellite, developed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Spartan-Halley’s observations were to contribute to integrated studies conducted by several international spacecraft. The STS-51L crew would deploy Spartan-Halley on the third mission day and retrieve it two days later after it completed its observations. The Teacher in Space activities consisted of two live sessions planned for the mission’s sixth day. The first, entitled “The Ultimate Field Trip,” sought to compare daily life aboard the space shuttle and on Earth, and the second, “Where We’re Going, Where We’ve Been, Why?” sought to explain the importance of conducting research in space. Several other lessons to describe physical phenomena in weightlessness were to be filmed for later distribution.

Left: At NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, engineers prepare the second Tracking and Data Relay System satellite for installation in Challenger’s payload bay. Middle: Engineers process the Spartan-Halley spacecraft before installation in Challenger’s payload bay. Right: The logo for NASA’s Teacher in Space program.

On Jan. 29, 1985, NASA announced the five-person crew for the STS-51L mission, consisting of Commander Francis R. “Dick” Scobee, Pilot Michael J. Smith, and Mission Specialists Ellison S. Onizuka, Judith A. Resnik, and Ronald E. McNair. Smith was the only spaceflight rookie while the other four had each completed one previous mission. At the time of the announcement, the mission planned to deploy the third Tracking and Data Relay System (TDRS) Satellite and included an opportunity to refly one of the two satellites returned to Earth during the STS-51A mission in November 1984. NASA decided to remove the second TDRS from a flight in March 1985 due to design issues, and following repairs, it became the primary payload for STS-51L, which for other reasons first slipped to December and then to January 1986. The delay created the opportunity to launch the Spartan-203 retrievable satellite to observe Comet Halley nearing its closest approach to the Sun in early 1986, and managers renamed the payload Spartan-Halley. Resnik had primary responsibilities for operating the shuttle’s remote manipulator system to deploy and retrieve the satellites, and although no spacewalks were planned for the mission, McNair and Onizuka trained to carry out any contingency spacewalk tasks, such as manually closing the payload bay doors.

Left: A technician helping STS-51L astronaut Ronald E. McNair don his spacesuit in preparation for spacewalk training in the Weightless Environment Training Facility (WETF) at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Middle: A technician helping Ellison S. Onizuka with his helmet to prepare for spacewalk training in the WETF. Right: McNair (top) and Onizuka during the spacewalk training run in the WETF.

Left: STS-51L astronauts Judith A. Resnik, left, and Michael J. Smith training to use the shuttle’s remote manipulator system. Right: STS-51L crew members Francis R. “Dick” Scobee, left, and Smith during a meeting in their office.

On Aug. 27, 1984, President Ronald W. Reagan announced that a teacher would be the first space flight participant on the space shuttle. NASA released the Teacher in Space Announcement of Opportunity on Nov. 8, 1984, for a flight opportunity in early 1986. From the more than 10,000 applicants, NASA selected 10 finalists to undergo interviews and medical screening at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, in July 1985. With the delay of STS-51L’s launch to January 1986, NASA announced on June 13, 1985, that the teacher in space would fly on that mission. On July 19, Vice President George H.W. Bush announced the winner of the competition, New Hampshire middle school teacher S. Christa McAuliffe, with Idaho teacher Barbara R. Morgan serving as her backup. The addition of McAuliffe to the STS-51L crew marked only the second time that NASA had assigned two women to a single mission. On Sep. 9, McAuliffe and Morgan traveled to JSC to meet their fellow STS-51L crewmates and begin training for the mission.

Left: The 10 Teacher in Space finalists pose in front of NASA’s KC-135 zero-gravity aircraft at Ellington Field in Houston in July 1985. Right: The Teacher in Space winners meet the STS-51L crew – Ellison S. Onizuka, Barbara R. Morgan, Francis R. “Dick” Scobee, S. Christa McAuliffe, Judith A. Resnik, Michael J. Smith, and Ronald E. McNair.

Left: S. Christa McAuliffe, left, and Barbara R. Morgan, right, get their first taste of space food with Charles T. Bourland, head of the food lab at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston. Right: Francis R. “Dick” Scobee, Ellison S. Onizuka, Judith A. Resnik, McAuliffe, Ronald E. McNair, and Michael J. Smith in the payload bay of the full

fuselage space shuttle trainer at JSC.

In 1984, the Hughes Corporation selected employees Gregory B. Jarvis and L. William Butterworth as prime and backup payload specialist candidates, respectively, originally assigned to participate in the company’s satellite deployment on the STS-51D mission in March 1985. Due to the addition of Utah Senator Edwin J. “Jake” Garn to that flight, their flight assignment first changed to STS-51I and then to STS-61C. The late addition of Florida Congressman C. William “Bill” Nelson to that flight bumped Jarvis again, and NASA finally added him to STS-51L on Oct. 25, 1985, rounding out the seven-member crew.

Left: Hughes Corporation payload specialists Gregory B. Jarvis and L. William Butterworth during their training for the STS-51D mission. Right: Barbara R. Morgan, left, Michael J. Smith, S. Christa McAuliffe, and Francis R. “Dick” Scobee prepare to board T-38 Talon aircraft at Ellington Field in Houston.

Left: STS-51L crew members Ellison S. Onizuka, left, Ronald E. McNair, S. Christa McAuliffe, Michael J. Smith, Judith A. Resnik, Gregory B. Jarvis, and Francis R. “Dick” Scobee during water evacuation training. Right: McAuliffe, left, Jarvis, Resnik, Smith, McNair, Onizuka, and Scobee during a preflight press conference on Dec. 13, 1985.

Left: Four members of the STS-51L crew on the flight deck of the shuttle crew compartment trainer (CCT) – Michael J. Smith, left, Ellison S. Onizuka, Judith A. Resnik, and Francis R. “Dick” Scobee. Right: Backup payload specialist Barbara R. Morgan, left, S. Christa McAuliffe, Gregory B. Jarvis, and Ronald E. McNair in the middeck of the

CCT on Dec. 17, 1985.

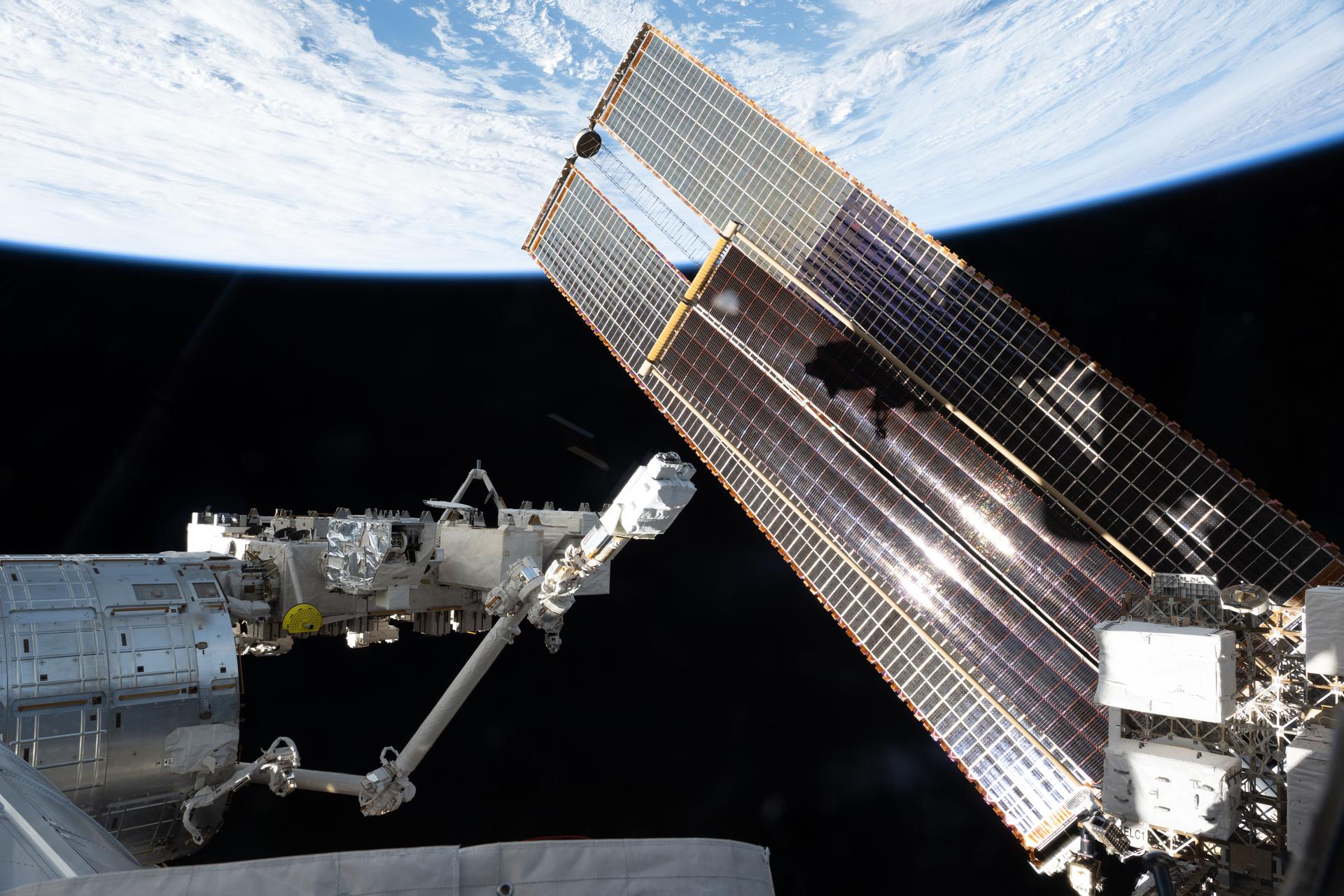

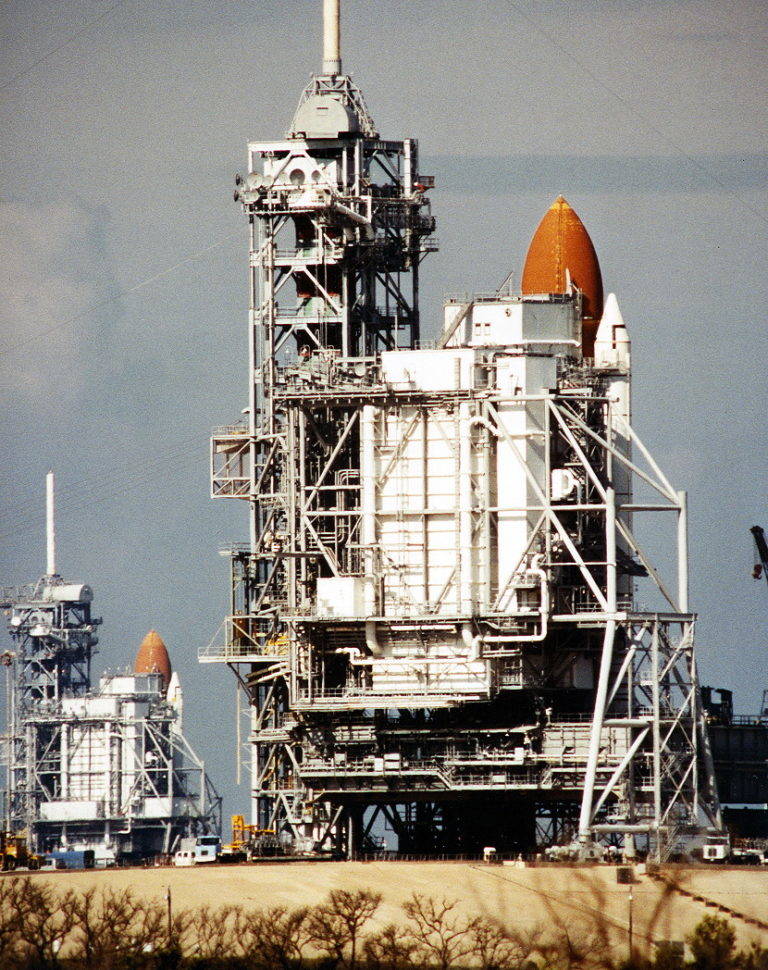

Workers at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) began preparing Challenger for its STS-51L mission immediately after it returned from its previous mission, STS-61A. After its arrival back at KSC on Nov. 11, 1985, they towed Challenger into the Orbiter Processing Facility to remove the Spacelab module from the payload bay and begin refurbishing the orbiter. Engineers installed the Spartan-Halley payload on Dec. 9 and one week later towed Challenger to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to attach it to its external tank and solid rocket boosters (SRBs). Rollout to Launch Pad 39B took place on Dec. 22, the first time the pad hosted a rocket since the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975. With space shuttle Columbia occupying Launch Pad 39A, awaiting its delayed launch on the STS-61C mission, this marked the first time that shuttles occupied both pads. The TDRS-B/IUS combination arrived at the pad on Jan. 5, 1986, and workers installed it in Challenger’s payload bay.

Left: Space shuttle Challenger during the rollout to Launch Pad 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. Middle: Aerial view of space shuttle Columbia on Launch Pad 39A, left, and space shuttle Challenger approaching Launch Pad 39B. Right: For the first time in history, space shuttles occupied both pads at Launch Complex 39, with Challenger on Pad B, left, and Columbia on Pad A.

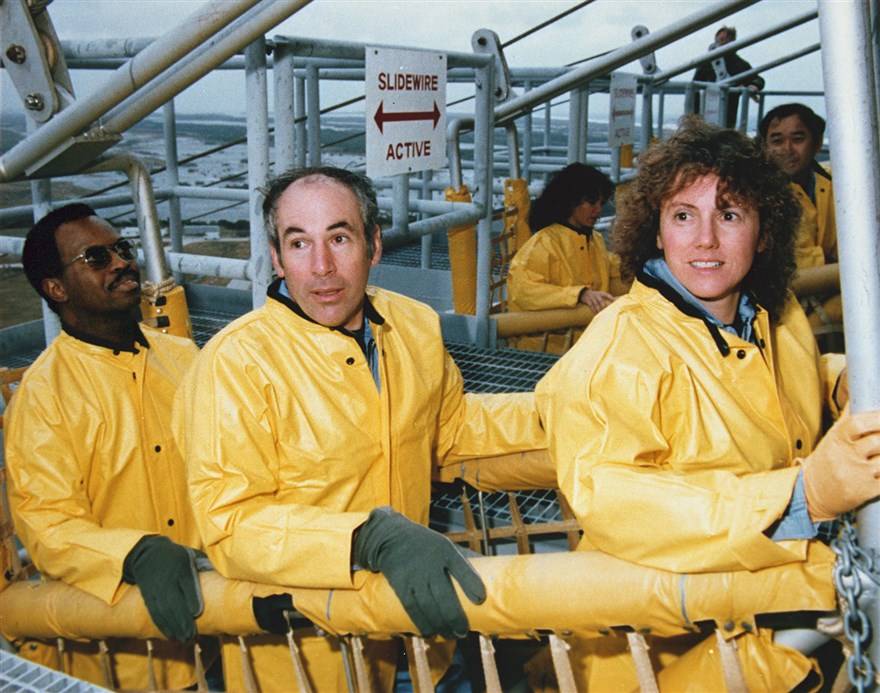

On Jan. 8 and 9, engineers at KSC conducted the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test (TCDT), essentially a dress rehearsal for the countdown to the launch itself. The STS-51L astronauts participated in the final stages of the TCDT by climbing aboard Challenger as they would on launch day, with the countdown being halted just before main engine ignition. At the launch pad, they participated in escape drills, climbing into rescue baskets they would use in case of an emergency. They also met with the media near the launch pad and answered reporters’ questions, posing for photographs with the shuttle in the background. After the successful conclusion of the TCDT, managers targeted Jan. 23 as the launch date but had to slip the date to Jan. 26 due to continued delays with STS-61C. The astronauts traveled from Houston to KSC on Jan. 24. With unfavorable weather projected for the 26th, managers slipped the launch by one day, to Jan. 27. The crew boarded Challenger for their first launch attempt, but managers scrubbed the launch, first due to a mechanical issue, and once it was resolved, winds at KSC violated launch constraints.

Left: STS-51L crew members S. Christa McAuliffe, left, Gregory B. Jarvis, Judith A. Resnik, Francis R. “Dick” Scobee, Ronald E. McNair, Michael J. Smith, and Ellison S. Onizuka pose in the White Room of Launch Pad 39B during the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test (TCDT). Middle: In the foreground basket, McNair, left, Jarvis, and McAuliffe, and in the rear basket, Resnik, left, and Onizuka, practice emergency escape procedures at Launch Pad 39B. Right: At the conclusion of the TCDT, Jarvis, left, Onizuka, McNair, Resnik, McAuliffe, Smith, and Scobee answer reporters’ questions in front of the Astrovan at Launch Pad 39B.

On Jan. 28, 1986, the astronauts once again boarded Challenger as managers had cleared the launch despite unexpectedly cold temperatures overnight at KSC. Managers considered significant ice covering parts of the launch tower as not enough of a concern to delay the launch. In behind-the-scenes discussions, concerns by engineers about the effects of the cold temperatures on the integrity of O-rings in SRB segment joints were overruled by managers who cleared Challenger to launch. Liftoff took place at 11:38 a.m. Eastern time.

Left: STS-51L astronauts Ellison S. Onizuka, left, S. Christa McAuliffe, Michael J. Smith, Francis R. “Dick” Scobee, Judith A. Resnik, Ronald E. McNair, and Gregory B. Jarvis enjoy the traditional prelaunch breakfast. Middle: STS-51L astronauts, front to back, Scobee, Resnik, McNair, Smith, McAuliffe, Onizuka, and Jarvis prepare to board the Astrovan for the ride out to Launch Pad 39B for the launch. Right: The launch of space shuttle Challenger on STS-51L.

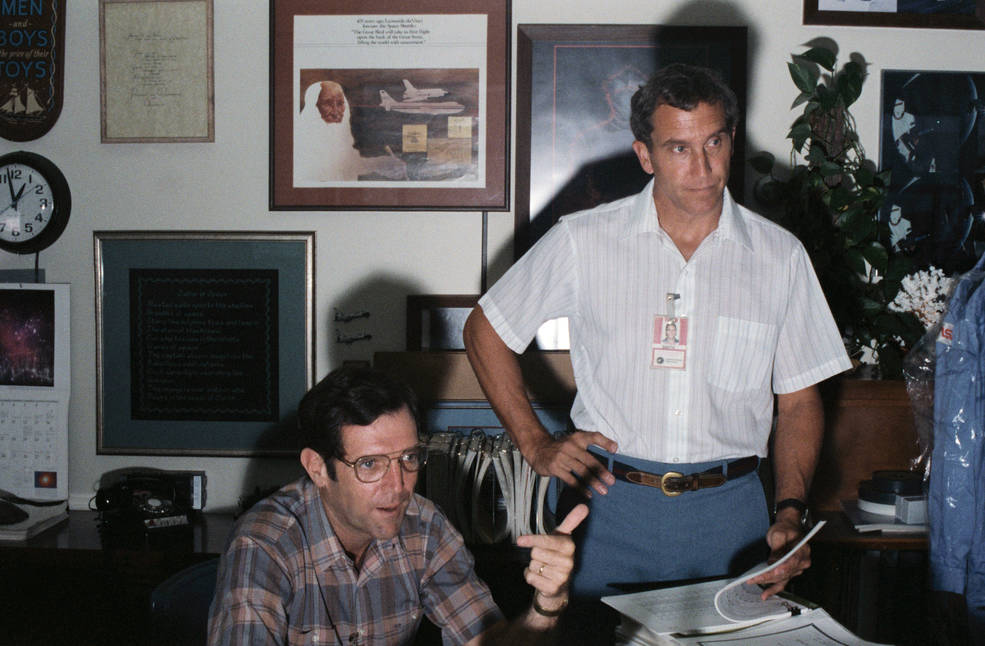

As soon as Challenger cleared the launch tower, control of the vehicle shifted from KSC’s Launch Control Center to the Mission Control Center (MCC) at JSC, where ascent Flight Director Jay H. Greene and his team monitored the mission’s progress. For the first minute or so, the launch appeared to proceed normally, with the usual callouts between the crew and capsule communicator Richard O. Covey in MCC. At 73 seconds after liftoff, controllers lost all telemetry from Challenger and noticed a fireball on television screens. Stunned controllers slowly came to realize that the vehicle had suffered a major malfunction that the crew likely did not survive.

Left: In the moments after the Challenger accident in the Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, capsule communicators Fredrick D. Gregory, left, and Richard O. Covey try to grasp the situation. Right: Ascent Flight Director Jay H. Greene in the moments after the accident.

Challenger’s Legacy

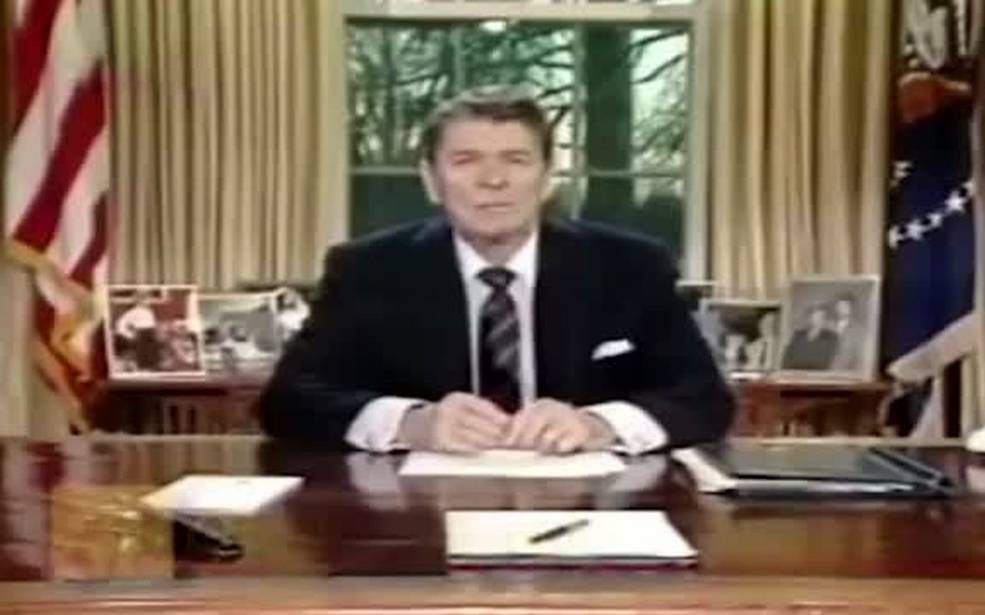

Left: President Ronald W. Reagan addresses the nation after the Challenger accident. Right: Members of the Rogers Presidential Commission examine a solid rocket booster segment.

In his address to the nation the evening after the accident, President Reagan eulogized the Challenger crew. Quoting aviator and poet John Gillespie Magee, he said, “We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.’” Reagan established a presidential commission, chaired by former Secretary of State William P. Rogers, to investigate the causes of the accident. The commission’s report, referred to as the Rogers Commission Report, summarized their findings of the technical causes of the accident as well as systemic organizational and cultural elements that led to the decision to launch Challenger on that day. The report provided recommendations to NASA on how to correct those deficiencies. With the modifications to the hardware completed and tested, shuttle flights resumed in September 1988, after a 32-month hiatus. The first seven missions after return to flight launched from Launch Pad 39B as workers refurbished Pad 39A.

Left: Logo of the Challenger Center for Space Science and Education. Right: Schoolchildren simulating a space flight at the Challenger Learning Center-St Louis. Credits: Challenger Center for Space Science and Education.

An enduring legacy of the Challenger accident is the Challenger Center for Space Science and Education, formed in 1986 by the families of the STS-51L astronauts. The Challenger Center and its worldwide network of Challenger Learning Centers, the first opened in Houston in 1988, use space-themed learning and role-playing to cultivate students’ skills for future success. These experiences enhance knowledge in science, technology, engineering, and math. To date, the Challenger Center has reached more than 5.5 million students globally.

Left: Expedition 50 Commander R. Shane Kimbrough with Ellison S. Onizuka’s soccer ball aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Middle: Onizuka’s soccer ball photographed in the Cupola of the ISS. Right: Close up of the faded inscription “Good Luck Shuttle Crew” on Onizuka’s soccer ball.

Onizuka’s daughter Janelle, then a soccer player at Clear Lake High School near JSC, gave him a ball, signed by her teammates, to take with him to space. After the accident, searchers found Onizuka’s personal preference kit, including the ball, and returned it to his family who donated it to the school where it sat on display for 30 years. NASA astronaut R. Shane Kimbrough took the ball with him to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2016, where it stayed for 173 days. After his return to Earth, during a football game halftime ceremony, Kimbrough returned the soccer ball to the Onizuka family, who in turn donated it to Clear Lake High School, where it remains on display.

Left: Mission Specialist Barbara R. Morgan during the STS-118 mission. Right: Educator astronauts Dorothy Metcalf-Lindenburger, left, Richard R. Arnold, and Joseph M. Acaba during weightlessness training.

In the wake of the Challenger accident, in 1990 NASA cancelled the Teacher in Space program, by which time Morgan had returned to teach in Idaho but maintained contact with the space agency. In 1998, NASA selected her as a mission specialist, and she flew aboard STS-118, a flight to the ISS in August 2007. That same year, NASA introduced the Educator Astronaut program, in which the agency selected qualified teachers as full-time astronauts instead of payload specialists. In the 2004 astronaut selection, the agency chose Joseph M. Acaba, Richard R. Arnold, and Dorothy Metcalf-Lindenburger as the first three educator astronauts. All three completed space shuttle missions, and Acaba and Arnold also flew long-duration missions aboard the ISS. In December 2020, NASA named Acaba to the team of astronauts eligible for missions to the Moon in the Artemis program.

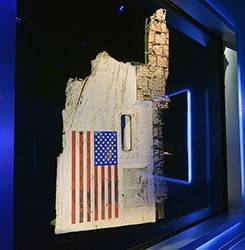

Left: Overview of the “Forever Remembered” exhibit at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex. Right: A section of the fuselage recovered from space shuttle Challenger.

“Forever Remembered”, a collaborative exhibit between NASA and the families of the astronauts lost in the Challenger and Columbia accidents, opened at the KSC Visitor Complex in 2015. The memorial honors the crews, pays tribute to the spacecraft, and emphasizes the importance of learning from the past. Displays include personal belongings from each of the crew members and recovered pieces from both Challenger and Columbia. Also at the KSC Visitor Complex, the names of the seven astronauts lost in the Challenger accident are engraved on the Space Mirror Memorial.

To honor the astronauts lost in the Challenger accident, as well as those lost in the Apollo 1 fire and the Columbia accident, every year at the end of January, NASA holds a Day of Remembrance. The day allows NASA employees to reflect not only on the lives lost but also on the circumstances that led to the accidents and the resulting changes to NASA’s operations and safety culture. It is also a time to ensure that everyone does their utmost to prevent future tragedies from happening through a heightened culture of safety and excellence.