Since the earliest days of America’s space program, telemetry has been used to track rockets and spacecraft. Similar technology now is being put to work by marine biologists to aid in studying activities of over a dozen managed fish and sea turtle species in the waters surrounding NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Fish spawned at the spaceport are now thriving and being tracked as far away as the coastal areas of New Jersey.

Established in 1962, the Kennedy security zone also functions as the oldest marine reserve in the United States. This has aided scientists at the spaceport who are partnering with counterparts from other government agencies and universities to aid in preserving many types of marine wildlife.

“This has been a huge success story,” said Eric Reyier, Ph.D., an InoMedic Health Applications Inc. fisheries biologist. “Our tagging efforts are helping us better understand and quantify the time Florida sport fish spend within the estuary around the space center.”

Reyier pointed out that Kennedy’s Ecological Program Office recently received notice from the U.S. Navy in Norfolk, Va., and the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife that two black drum fish, tagged with small transmitters at the Florida spaceport, were detected in Chesapeake Bay in May and one later was recorded off the coast of New Jersey. This finding represents the longest migration ever documented for the black drum species.

A popular sport fish, black drum are common to bays and lagoons but also may be found offshore. They tend to be bottom dwellers, often feeding on oysters.

“Along with the black drum, we have also tagged numerous other species such as red drum, spotted sea trout, sheepshead, tarpon, gray snapper, common snook and lemon sharks,” Reyier said. “We’ve also tagged numerous green sea turtles to document their life cycle and movements.”

In addition to being a 140,000-acre spaceport, Kennedy also is part of the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge established in 1963. It provides a habitat for more than 1,500 species of plants and animals. Add to that the necessary security surrounding Kennedy and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, and what results is a highly protected environment for local wildlife.

“This gave us a protected area to study exploited fish that are economically valuable,” Reyier said. “While this enhances the fisheries throughout east-central Florida, they can also have positive impacts on fisheries over much larger sections of the U.S. East Coast as the black drum example shows.”

Marine life that has value for sport or food can be fished, or exploited, to the point where the numbers are diminished. While that may not lead to the species being endangered, coordinated efforts may be needed to, again, make the fish plentiful.

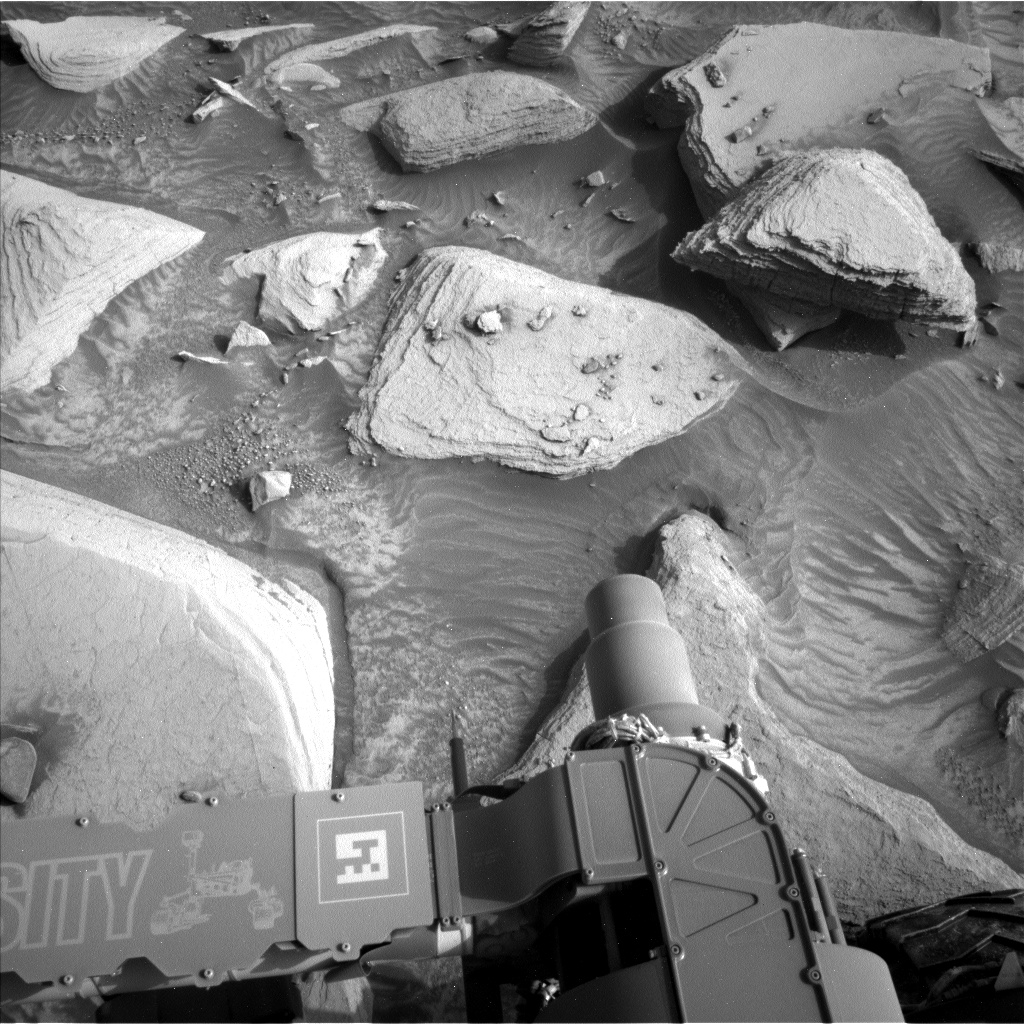

“We started tagging sport fish in 2008,” Reyier said. “We often just use a large cast net to catch a fish in the many marshes and estuaries at Kennedy that are shallow and only ankle or knee-deep.”

The captured fish is sedated with a chemical so it isn’t hurt, a small incision is made, the transmitter is inserted, the incision is stitched closed and the fish is released.

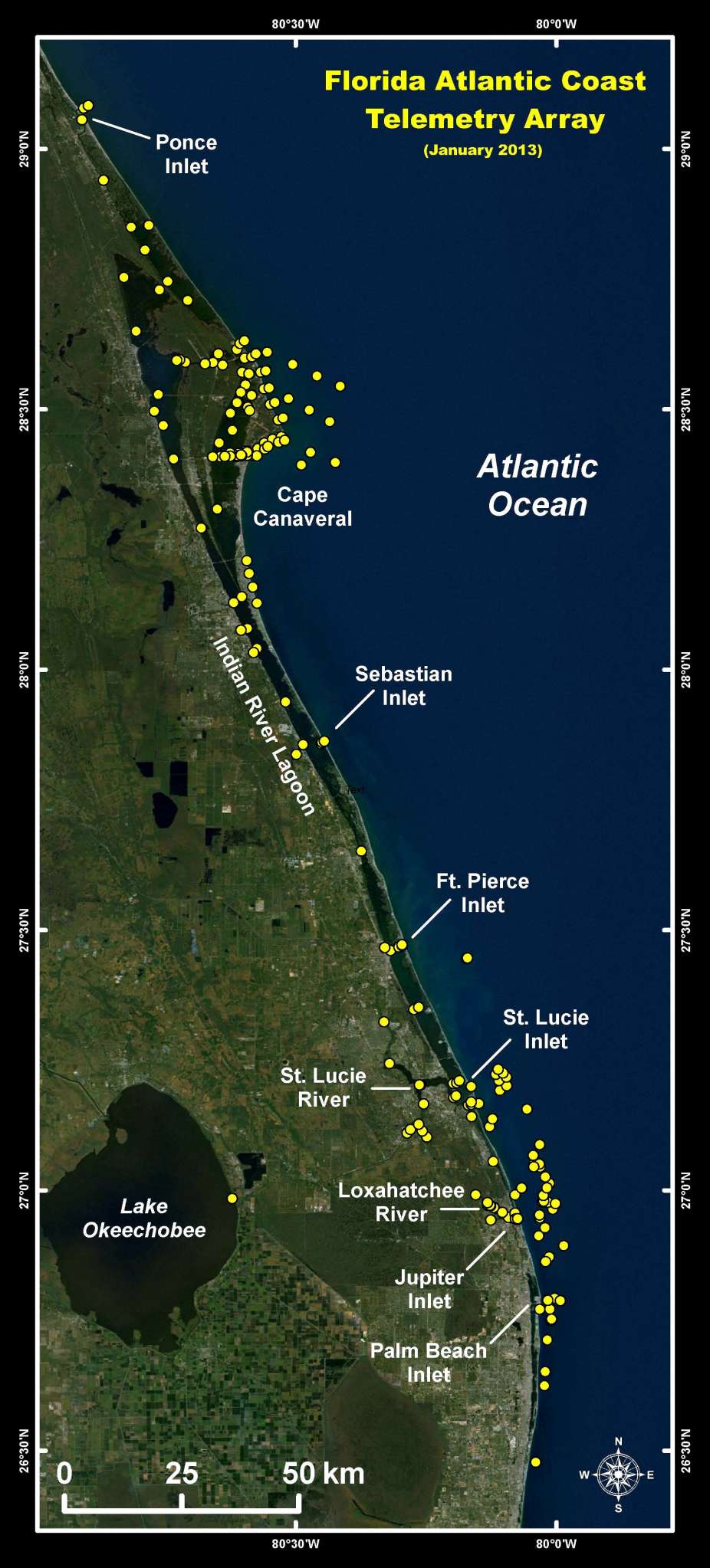

The transmitters placed in the fish are slightly smaller than a tube of lipstick, but can last up to 10 years. Receivers are about the size of an aerosol spray can and are placed in the waters around the space center and the adjacent shore. When any fish with a transmitter swims within 500 meters — about 547 yards — the movement will be recorded.

Periodically, Reyier or other biologists retrieve the receivers, plug them into a laptop computer and download data that has been recorded.

“Cooperation from numerous organizations collecting similar data has been very helpful,” he said.

Receivers similar to the ones placed in the waters around Kennedy are being positioned up and down the eastern seaboard of the United States by organizations with similar interests in studying the life and migration habits of fish.

“We now are partnering with several universities and other government agencies and sharing what we learn,” Reyier said.

Biologists from the U.S. Navy, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, have joined forces with the University of Miami’s Bimini Biological Field Station, the Florida Program for Shark Research at the University of Florida, University of Central Florida, Florida Institute of Technology, University of North Florida, Florida International University and Stony Brook State University of New York.

“With so many organizations participating, a great deal of data can be shared with an economy of effort and cost,” said Reyier. “In addition to partner groups reporting their findings about fish tagged here, we’ve been able to pass along information to others on the migration of fish tagged with transmitters originally released as far away as Delaware, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts.”

Experts with Kennedy’s Ecological Program have noted that understanding how and why animals move through their environment is important to better understanding their role within a given ecosystem — a community of living organisms along with other components of their environment.

“From a practical standpoint, this data also helps streamline environmental permitting requirements and, most importantly, helps us identify critical habitats such as fish spawning and schooling areas so human disturbance to these sites can be minimized,” said Reyier.

In recent years, telemetry systems have become low-cost, powerful tools in learning about the behavior of marine organisms, habitat preferences and migration patterns without reliance on direct observations or recapturing animals.

“It’s a necessary step for developing sound management strategies for exploited and imperiled species,” Reyier said. “The duration and geographic scope of these studies of fish and other mobile animals is giving us valuable new insights which are directly benefiting our conservation efforts.”