Andres Almeida (Host): For decades, flying faster than the speed of sound over land has been off-limits for commercial passengers. But it’s not speed that’s really the limit. It’s sound. Sonic booms, to be precise.

On this episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps, we explore how NASA is working to bring supersonic flight back quietly with the X-59 experimental plane.

Our guest is David “Nils” Larson, lead research pilot at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California. Nils takes us inside the science and engineering required to transform a disruptive sonic boom…

[SFX sonic boom shockwave]

…into a gentler sonic thump.

[SFX quiet sonic thump]

And explains how this experimental aircraft could help reshape the future of air travel.

This is Small Steps, Giant Leaps.

The first of several flight tests of the X-59 took place in October of 2025. While this flight was not supersonic, the successful takeoff and landing demonstrated the prowess of the design and engineering teams. What we learn could lead to a giant leap in how we move around the world.

Host: Hi Nils, welcome to the podcast.

David “Nils” Larson: Thank you for having me.

Host: Can you kick us off with giving us a little bit of background on what the X-59 Quesst mission is?

Nils Larson: Sure. The only people who can go supersonic over land are essentially the government or people with special permission. So, the military and NASA can do it for our research.

You know, the Concorde used to fly supersonic, but it couldn’t go supersonic over land. So, over 50 years, we’ve had a ban on supersonic flight over land. And it’s a ban because of that sonic boom. So, if you don’t go faster than the speed of sound, you don’t make the boom.

So, our “quest,” if you will, is to get the data, and we’re trying to take that sonic boom and turn it into a sonic “thump.”

And if we can turn it into a sonic thump, something that’s not displeasurable to the public, then we can turn around, maybe, and turn that speed limit into a sound limit.

So, the short bite is turning a speed limit into a sound limit. And there’s many different ways, or many different processes or steps that we have to do in order to make that happen.

Host: It’s uncomfortable for the public, right, to hear a sonic boom? Is it also structurally unsound to do that, so to speak?

Nils Larson: If you were really low, it might rattle or break some windows or something like that. I mean, but you got to be really low, really fast.

But generally speaking, for where an airliner is going to fly, or, you know, where military airplanes, you know, nice and high generally, when you’re going to go supersonic, for the purposes of getting people from point A to point B, you’re not going to break any glass. The biggest thing is just that noise.

And most people you know out here, we hear sonic booms all the time. You know, out here in California, at Edwards Air Force Base.

Most people don’t realize they’ve actually heard a sonic boom. Thunder is a sonic boom.

Host: What features of the X-59 make a sonic thump possible?

Nils Larson: Great question. Many different things across the airplane help to change that sonic boom into a sonic thump.

If you look at a picture of the airplane, the first thing you’re going to notice is that really big, long nose. So, there’s your first clue: Why in the world would you build something, you know, with a sword, it looks like, sticking out the front of the airplane? And that’s probably the biggest thing.

And most of the time you hear a sonic boom. It’s a “boom-boom.” So, we’ll just say that that’s kind of the front shock and the tail shock, or how they kind of come together to form a front and a tail shock. So that big, long nose helps to kind of lower the loudness of that front “boom” that you get (the “boom-boom”).

And it also kind of spreads it over time a little bit. So, it’s not like that startling firecracker that you get. Because if you spread that over just a couple of milli-slash-nanoseconds, it’s not quite as bad, because it doesn’t startle you as much. So that’s one of the big things.

The other thing you’ll see is you’ll notice that the engine is on the top of the airplane. We try not to put very many things on the bottom of the airplane, because that’s where all the shock waves are created that are going down toward the ground. You know, stuff that’s going up into space? Yeah, we don’t care about that so much.

Host: Will you, as a pilot, be able to hear any of those sonic thumps?

Nils Larson: No, it’s actually kind of funny. Like, in the airplane, you don’t hear a sonic boom. You don’t hear anything — you don’t even know most of the time that you’re going supersonic, except the Mach gauge says 1.0 or 1.11 or whatever.

The other thing you might see when you go supersonic is you might see the altimeter swing around, just because as the shock wave goes over the static port on the airplane (and that’s the pressure port that looks at the static pressure of the atmosphere), well, that’s what feeds your altimeter. So, when the shock wave goes across that, there’s a change in pressure across that, so, you might see the altimeter swing back and forth as that shock wave goes across the static port. So, most of the time, you never know that you’re supersonic, other than, you know your gauges telling you that you’re supersonic.

Host: And you know all this so well because you’ve been involved in the design of the X-59 plane. How has that shaped the way you approached the first flight test?

Nils Larson: It’s been great to get to work on this thing since before it was a thing.

So, Clue and I (he’s the other test pilot from NASA), we helped write the requirements for the airplane early on. We’ve been involved with it since day one.

One of the big things that really helped for first flight, and it’ll help for all the rest of the flights as well, is the external vision system. So, if you look at a big, long nose, you know, there is no front windscreen.

So, you know, like Charles Lindbergh, you know, he didn’t have a front windscreen either, but I can’t hang my head out the side. It just ain’t gonna work.

In this case, we have a monitor, a 4K monitor, and then we have a 4K camera on the top, and then we have a HUD camera on the bottom that would be for a commercial business jet or something like that. And it’s a lower resolution, and that’s actually made by NASA Langley.

And the folks out of there that is their — I’ll call it an experiment because it’s not certified like other parts that are on the airplane — but Randy Bailey and his group there have done just an amazing job of designing that so that I can see out the front. They’ve given me a lot of different tools in that XVS (or external vision system) that we have.

Now, when we come in to land, and I need to flare to land, much like the space shuttle if you’ve ever seen, you know, space shuttle videos, there’s a flare cue that comes up. They’re these little pluses that come up with a radar altimeter and start marching up. And I just take the flight path marker and I just kind of follow it up. As we always say, “Put the thing on the thing until the other thing, and then just let it land.” So, just kind of pull it up and then hold it just below the horizon and let the airplane set down.

So, we were involved with Randy when it came to what kind of things that we wanted on that. Randy’s been great about suggesting things because he’s worked in displays forever. So, he’s like, “Hey, do you want this? And we’re like, yes, we want that.” And other times we’d come to him and go, “Can you give me this?” And he’s like, “Yeah, I can give that for you.” So, working with the folks at Langley on the XVS system has just been amazing.

The other great thing is working with Randy, you know, from some of the stories, when we work with Collins on some of the other avionics, there will be times that we look at stuff (and he’s been a researcher doing this stuff forever), we’ll look at something, we go, “I like that. Hey, Randy. Should I like that?” And he’s like, “Yes, you should like that.”

Okay, so, because he has the knowledge and the background of the research that went into why we make it that color, that thickness, or whatever it happens to be. So, that’s an example of some of the design influences we had, and something that we used in first flight, and, you know, trying to land this thing for the first time, you know, you got to get it back on the ground.

The whole purpose of a first flight is to land. I had other ways to get the airplane back on the ground if the XPS didn’t work, but we knew it was going to work, and it worked like a champ.

Host: With all these ideas thrown in there, there had to have been some engineering challenges. Can you share some?

Nils Larson: Always. We’ve had other X-planes in the last few decades, but they haven’t been manned since, essentially, probably X-31, and now we’re on X-59.

I flew the X-48C and that was remotely piloted. So, it’s not necessarily a challenge, because the X-1 and all those earlier ones, those had humans in them. So, that wasn’t necessarily as much of a challenge. But where this plane will fly, typically above, you know, 50,000 feet and up to 60,000 feet, that meant that we probably need some form of a life support system.

Normally when you fly that high, you wear a full pressure suit, but if you look at that cockpit, it ain’t real big.

So, you know, years ago, when we were doing some of the design studies, they put me in a full pressure suit in the back of a T-38, which is what the cockpit is designed around for the X-59, and shoehorned me in the back and closed it up and said, “What do you think?” And I said, “No, this ain’t gonna work.”

So, what we have is kind of a partial pressure suit that we’ll wear for going high, which is the same garment that’s on the F-22 so it’s a g-suit, and it’s a chest garment, and it’s a helmet with a bladder in it. And it’s designed essentially to keep us alive should we lose pressurization just so that we can get the airplane down.

So, that’s one of the unique challenges for this airplane, for something that we had to design around. But that was done way early and there’s other implications with that.

Like, if you had to eject. The ejection seat we had –the ejection bottles weren’t, you know, sized for being able to fall from that far. So, we had to up the bottles for the emergency oxygen. So, there’s other little repercussions. Once you redesign one thing, you got to figure out all the other ones. Like, what else did that cause that we got to fix as well?

There’s always a challenge with an airplane like this. Because it’s a fly-by-wire airplane. It’s really weird-looking because, you know, it’s almost 100 feet long, 30 feet wide. It’s got four lifting surfaces on it: A canard, a wing, you know, a stab, and a T-tail. And that’s some of that other special sauce to keep that thump low by changing the distribution of the lift over the airplane. That helps with the tail shock.

But with all that, you have the flight controls that they have to design for this weird airplane that, if this airplane had the computers die on it, it wouldn’t be able to fly. And it would pitch up almost instantly and depart. So, you know, if you lose electricity, so you have to have backup systems for that. And you know, so there’s, there’s many challenges just because of the unique design of the airplane.

Host: And you’re probably thinking about what’s acceptable risk throughout this whole design process, right?

Nils Larson: You’re exactly right, yeah. I mean, there’s things that we do on this airplane that we would not do if it as a commercial airliner, or if it was a production airplane, you know, for the military or something in small numbers, large numbers.

There are certain, you’re right, certain risks that we look and we say, “Okay, we’re willing to accept that,” because test pilots are the only people that are going to fly it and they have a lot of experience. That’s not your go-to thing. Normally, you want to engineer out the problem. That’s number one. And then you’re looking for procedures and training and experience. All that should be last.

Host: And we should clarify that this is an experimental plane, so in the future, it could influence design. But that’s likely not the final design of a, say, commercial airliner down the road. Is that fair to say?

Nils Larson: Oh, that’s exactly right. It is not a prototype, you know, it is a research demonstrator. So, it is researching those techniques that I talk about, and there’s many others, are the different techniques that we would use, you know, for a future supersonic airliner.

So, I like to say that, you know, if you saw supersonic airliner of the future, you know, it wouldn’t look exactly like the X-59 but you could see pieces of the X-59’s DNA in it. It would probably be long and skinny. It would probably have some form of a big, long nose. It might not, it might be a retractable nose, you know, or something like that so that it’s shorter when you land.

If you remember, the Concorde used to droop the nose so they could see to land. So, it might have an extending nose, or it might have an extending tail boom as well. There’s many different things. A future aircraft, you could look and go, “Oh yeah, that’s the grandson of the X-59.”

Host: I want to pivot a little bit toward your training also. The way you train, actually, because you trained Artemis II astronaut Vic Glover. Do you find many parallels with aeronautics and the way you approach training an astronaut to fly in space?

Nils Larson: Yeah. Victor was one of my students when he went through Air Force Test Pilot School, and I was an instructor as an adjunct instructor there on the staff. I taught at both Navy and Air Force Test Pilot School.

So, a couple of astronauts in the astronaut office, like Komrade [Randy] Bresnik, was a student of mine, and then he and I were instructors together. Other astronauts that are out there were classmates of mine from Air Force Academy and, and other things. So, so it’s always fun to live vicariously through them whenever they get to do, you know, great things out there. I’m really excited for Victor. I can’t wait to see him up there going around the Moon.

But a lot of the same techniques, you know, all the stuff, like Artemis, it’s, it’s an experimental flight, just like the one that I just did. So, the techniques that we taught, you know, Victor and Komrade back there in the school, and the stuff that Komrade was an instructor, too, and that he taught, those are the same things that they’re looking now.

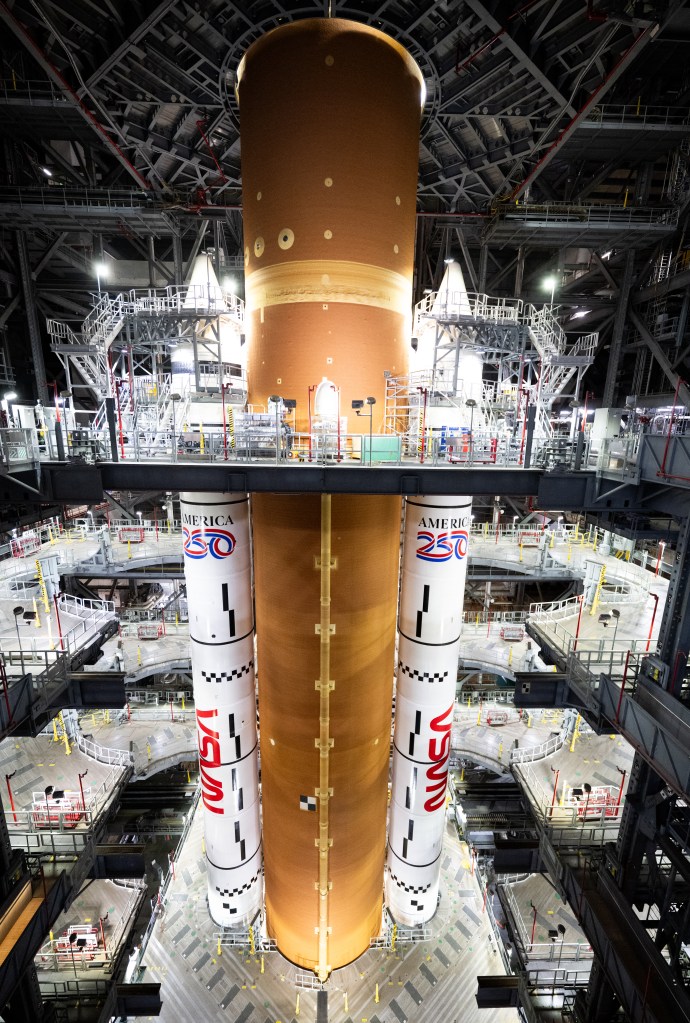

If you look at the position like that Komrade’s in and what he’s doing now, is he’s helping to do some of the same stuff I just do what X-59: looking at the designs of, you know, the different, you know, landers and the SLS system, you know. So, it’s, it’s all the same stuff. It’s just a different environment. It’s in space. They don’t have to fly, they just get to fall. So, let gravity take control.

So, there are a lot of – a lot of similarities, and a lot of overlap. You know, if you were to take out the Venn diagram and you would see the intersection of those circles, it would be a pretty good intersection, the circles. I would say, well over 50%, probably more like 70 to 80% of what goes on. It’s just a lot of the stuff in the environment is different. You know, obviously your propulsion systems are going to be different.

But, you know, if you think about it, for us, we solved our problem differently for being above 50,000 feet. But it is a same problem that they have when it comes to, you know, their environment.

And when it came to our aircraft, some of the doctors on the board are actually, you know, some of the JSC flight surgeons who were some of the people that were, you know, questioning us and making sure, you know, they would look at how we were designing different things. The good thing was, I was a former U2 pilot and an ER-2 pilot for NASA, so I was used to the high-altitude environment. So, from day one, you know, I was able to help influence the design.

And even before it was a design, when they said, “Well, we can’t go above 50.” And I said, “Sure, you can. You just got to do it right.” There are many parallels between us and the space side.

I mean, I actually have an – my degree is in astronautical engineering and propulsion. I actually worked at Lewis Research Center when I was an intern years and years ago. I don’t care to say how long ago that was, but it was a long time ago, because, obviously, because it was Lewis, but I worked on arcjet engines and had a lot of great memories working back there at Lewis, now Glenn [Research Center].

Host: How do you ensure that knowledge gets transferred and there’s a sharing of knowledge between teams?

Nils Larson: I hate to say it, but there’s a lot of meetings. So, there’s a lot of meetings that do that. I mean, obviously when we do a test, there’s always a flight report.

So, we have the debrief, just like you would see the astronauts when they come back from a mission, they have their debrief. We do the same thing.

If we have any test event, you know, that gets debriefed, and you have all the different people in the room, you know, representing all the different disciplines of engineering. And then they’ll, you know, note what they saw. I’ll note what I saw.

Then, of course, I write a flight report, you know, and each of them are going to write a flight report. Then we have, usually, the chief engineer is going to scoop all that stuff together. And depending on — it, may be several flights that they’ll cover like in the future, or it might be like for us, like a single flight, and they’ll get everybody together. And everybody, you know, presents a really quick “this is what we saw.” So, a lot of times it’s like, “Great! Nothing wrong with your system.” Somebody else goes, “Well, mine could use a little work.” So, that’s probably, you know, the best way to do it.

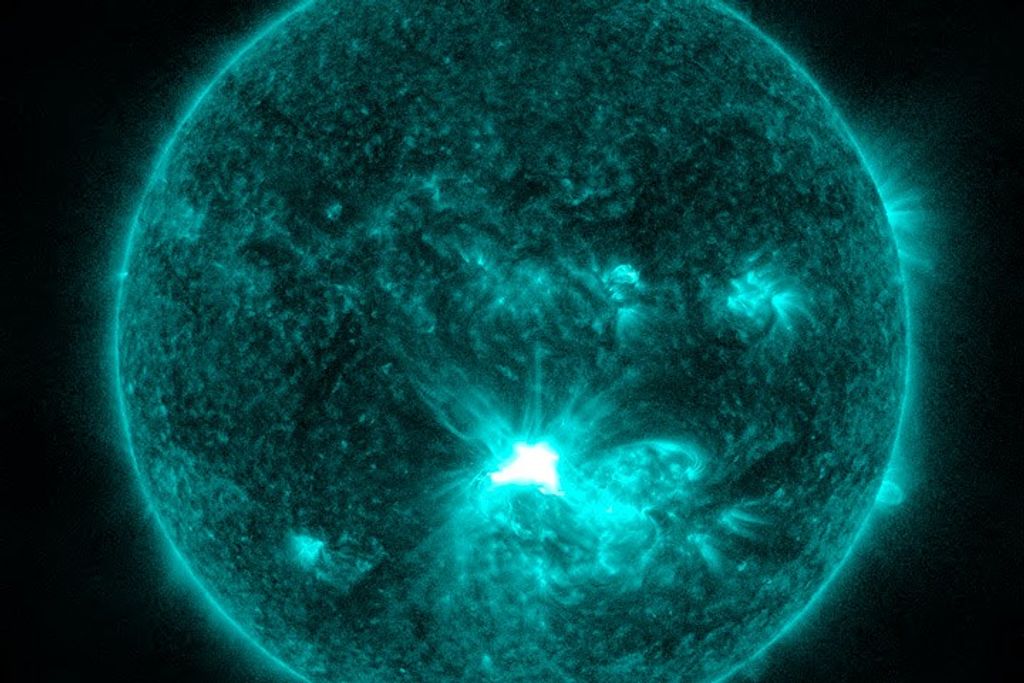

And one of the best ways I found from other flight tests that we were working on was, especially when we were moving quickly. We were doing some sonic boom work. We were trying to get those Schlieren pictures (where you see the pictures of the shock wave) and like any time thing, we’re running out of time and money. We needed to get this done, so, we’re trying to fly several flights in that day.

So, what we did was we had all the pilots attend the debrief of the pilot, you know, of all the other pilots. So, when we did the debrief, they could give their lessons learned instantly to the person who was about to fly and go step to their, you know, the airplane once they refueled it. So, it worked like a champ, because they said, “This is what I did that worked. This is what I did that didn’t work. You know, this is what I think you should do.”

And then, sure enough, you come down from the next one, and then you, you have that knowledge transfer really quickly. So, it’s all about communication, and whatever communication you use with those tools, whether it’s written or whether it’s a Teams meeting or any other kind of meeting. And depending on when you need that data, you know, it’s how much you got to crunch that down.

You know, it can be very intensive trying to get the word out there. The biggest thing is, obviously, if it’s something that’s really important, you really want to get a good face-to-face, like with the other pilot. If there’s something that we really didn’t like, then I want to go grab hold of Clue. You know, he’s the other test pilot, Jim “Clue” Less. And I say, “You know, hey, Clue, watch this. You know, we’re gonna go over to the sim and try this, because this, this was kind of something, you know, I didn’t like.”

It’s part of what we’re here for as NASA. You know, on the research side and everything is to go get the data, go get the research, the techniques and all that, and then give it to everybody else, you know, to advance, you know, technologies and knowledge.

I think one of my quotes are “Lessons learned aren’t learned unless they’re taught.” So, it doesn’t do you any good to go leave it on the shelf somewhere.

That’s why getting out to conferences is so important. And sometimes it’s not just to present papers, sometimes it’s to be able to be on the receiving end.

I mean, I don’t know if you look at my notebook every time I go to one of these conferences where people are presenting papers, you know, it’s almost like I’ve written my own paper while I was there. Of all the ideas, that one thing spurs the next idea and, “Oh, I got to make sure that we include this.” So, to me, that’s one of the great areas of knowledge transfer is being able to go to conferences. And that’s, that’s something that, to me, has, has always been just hugely important.

Host: What’s next for the X-59?

Nils Larson: Sure, so I think you alluded to it earlier. It’s just the first flight, which is awesome! Don’t get me wrong. And getting to do that was such a privilege.

But when you look at what it is, I keep saying, like, after we flew the first flight, I’m like, “Hey, that’s great! You realize this is just chapter one?” And the prologue was all the stuff that we just did. You know, all the building and ground testing and all the other stuff. We’re in chapter one. And this is a three-volume set! This isn’t even, you know, so this is the first chapter of the first book.

So, this is Phase One, and this is what you’ve heard of, what we call envelope expansion. So, right now, we’ll be going higher and faster and checking out all the systems on the airplane to make sure, you know, that it’s safe. And, you know, that is the envelope expansion portion.

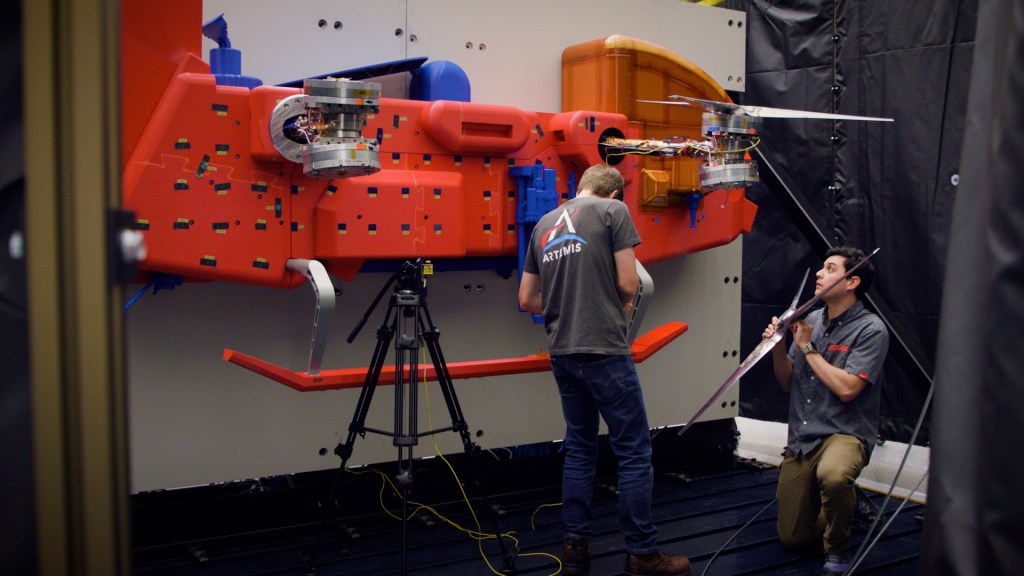

Phase Two, now we’re going to look at that sonic thump, where you have all kinds of ground recording stations. We’re also going to probe the airplane at altitude with an F-15 that’s got a special probe so we can look at the shock waves right next to the X-59. We can see how those come together to form the boom on the ground. So, we have several different things that we will do to make sure that our design is actually what we’re getting.

Now, we do have the ability to tweak some stuff, if you will, in the design and that, I can actually change some of the flight control surfaces and bias them if we need to, if we’re trying to change the shape, you know, of what is actually coming off the airplane. So, we do have a little bit of, you know, ability to change that. So, that would be what we call Phase Two.

And then Phase Three is the other big phase. And in Phase Three, that’s where we call it the traveling road show. And this is very unique for an X plane, because most X planes just live at Edwards or Pax River or something like that. Well, we got to take this thing on the road, and we have to take it out to communities in the United States and various environments, you know, because the sound travels differently in different environments.

And so, we have to get the public to tell us, “Yeah, that was acceptable.” Or, “Nah, that was a little too much.” So, ultimately, when we get this data, we can turn to the regulators, like to the FAA and to ICAO, which is the International Civil Aviation Organization, I think, so essentially the “worldwide FAA,” and say, “Here’s the data. Will you change the regulation from a speed limit to this sound limit?” And hopefully they’ll do that, and that would open up a whole new industry and ways for us to get to Grandma’s house faster.

Host: Grandma would be happy. My final question for you: What was your giant leap?

Nils Larson: That’s a great question. And when you sent me the advanced questions. I’m like, “Hoo! How am I gonna answer this one?” Because I think sometimes in your life you have several giant leaps. But I’ll go with the first one, and that was, you know, deciding to be a test pilot.

So, you know, there’s many people that are out there and, you know, listen to your podcast, and I decided when I was 16 years old that I wanted to do what I’m doing right now, which, you know, just flabbergasted my wife. “She’s like, how the world did you know?” But I had, you know, teachers influence our lives so much. They are just so great. I had a teacher who really knew me, and he handed me a book, and the book was The Right Stuff. And he said, Read this. And I said, “Why?” And he said, “Just read it.” And I read it, and I went, “Oh, that’s cool.”

Because I thought I wanted to be an aerospace engineer, but I went, “I can be an aerospace engineer and a pilot. And maybe have a shot at being an astronaut.” How many people get to do that?” You know, I mean, there are more people that drafted by the NFL in a year than, you know, than there are who go through a test pilot school, by far.

Well, number one, I couldn’t go play for the NFL.

So, you know, I just wasn’t going to have those talents. But I was relatively smart, and so I said, you know, “What do I got to do, to go do this?” So just basically set out and said, “Okay, here’s what I need to do.” And I ended up going to the Air Force Academy, you know, and got my degree there, and then set off to pilot training, and then, you know, and just tried to get the experience.

And as soon as I got the experience, I applied to test pilot school, and they looked at my stuff when I first showed up, and they said, “You’re not going to get in the first round, probably because you need a little more experience, but you should apply again. You’ll probably get in eventually.”

So, if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. And then same thing when I came to NASA later in my career in the Air Force, when I applied to NASA the first time. You know, I applied to the astronaut [corps], and they never really looked at me, but on the test pilot side, they looked and said, “Whoo, you know, I don’t know that we have a job for you this round, but you got a unique background, so I think we might have a job for you here one day.” You should apply again whenever a job comes open. And sure enough, the second time I got in.

So, to me, the big leap was probably, you know, making that decision in the beginning.

And for everyone, I always look and I go, if you got a passion, somebody’s got to do it. Why not you? Go for it. If you got the passion and the talent, you know, or at least, even a, you know, a hint of the talent, you know, go get the training and the experience and give it a shot. Because somebody’s got to be an astronaut. Somebody’s got to be a test pilot. Somebody’s got to be a podcaster. You know, whatever it is that you want to go do, give it a shot. You know, why not you? Somebody’s got to do it. Why not you?

Host: “Why not you?” I love that, yeah.

That’s great. Well, thank you, Nils. Thanks for your time. We look forward to knowing more about lessons learned from the X-59’s flights. And thanks so much for sharing your insights.

Nils Larson: Well, thanks! And I’m looking forward to sharing some more as we go through Phase One and Phase Two and Phase Three.

Host: That’s it for this episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps. For a transcript and to hear other episodes, visit nasa.gov/podcasts. And don’t forget to check out our other podcasts like Houston, We Have a Podcast, Curious Universe, and Universo curioso de la NASA. As always, thanks for listening.

Outro: This is an official NASA podcast.