Andres Almeida (Host): Imagine you’re in a Moon lander about to touch down on the lunar surface. From your window, you see the lunar habitat where you’ll be living and working for the next few weeks – or months. Seconds before arriving, the engines fire for a gentle touchdown.

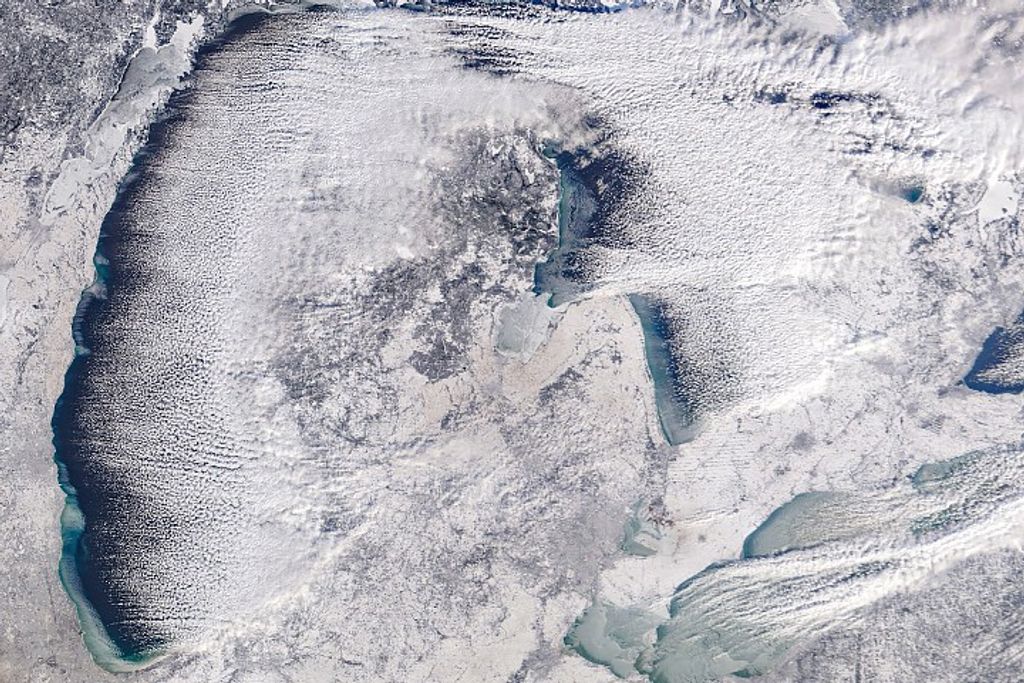

But rocks and dust kick up. With the Moon’s little atmosphere and low gravity, these particles fly far.

Does your habitat already have a protective shield? Did any rocks hit your spacecraft? What about the possible crater your lander created? These are just a few of the factors NASA engineers are looking at for future deep space missions.

To get it right, researchers first have to create simulated lunar and Martian soil, called regolith, here on Earth.

In today’s episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps, we’re talking with Dr. Jennifer Edmunson, project manager for NASA’s Moon to Mars Planetary Autonomous Construction Technology project, or MMPACT for short. She’s also the lead for the agency’s regolith simulant program at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. She’s here to talk to us about why these simulants are essential, what it takes to create them, and the lessons learned from preparing for construction beyond Earth.

This is Small Steps, Giant Leaps.

[Intro music]

Welcome to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, the podcast from NASA’s Academy for Program/Project & Engineering Leadership, or APPEL. I’m your host, Andres Almeida.

I’m here with Jennifer, ready to get the dirt on simulating regolith.

Host: Hey, Jennifer, welcome to the podcast.

Dr. Jennifer Edmunson: I’m so happy to be here. Thanks for having me.

Host: Of course. Can you tell us a little bit about what you do at Marshall?

Dr. Edmunson: I am currently the Moon to Mars Planetary Autonomous Construction Technology (MMPACT) Project Manager. I am also the project manager for the regolith simulant program out of the Game Changing Development Program.

I am also the acting program manager for Centennial Challenges, and I’m working with Langley to help develop a Raman spectrometer for hopefully lunar surface use. So, lots of different things.

Host: Why is it important to simulate lunar and Martian regolith?

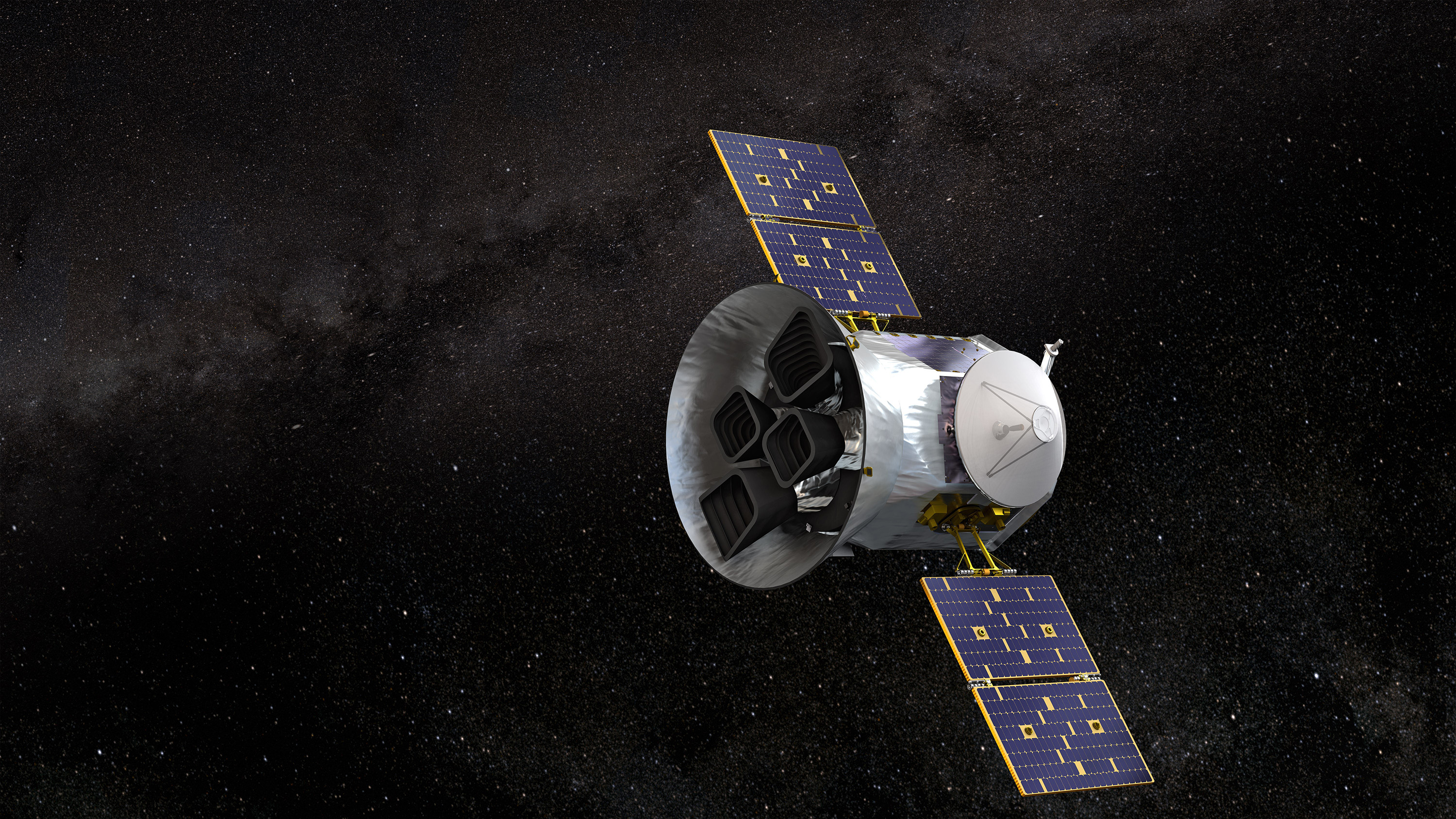

Dr. Edmunson: When we use regolith simulants, the reason that we use them is because we’re trying to raise the technology readiness level. We need something that will act like the lunar or the Martian surface or asteroid surface, so that we could test our technologies and make sure that when they get to whatever their destination is, they’re going to perform as we anticipate they’re going to perform.

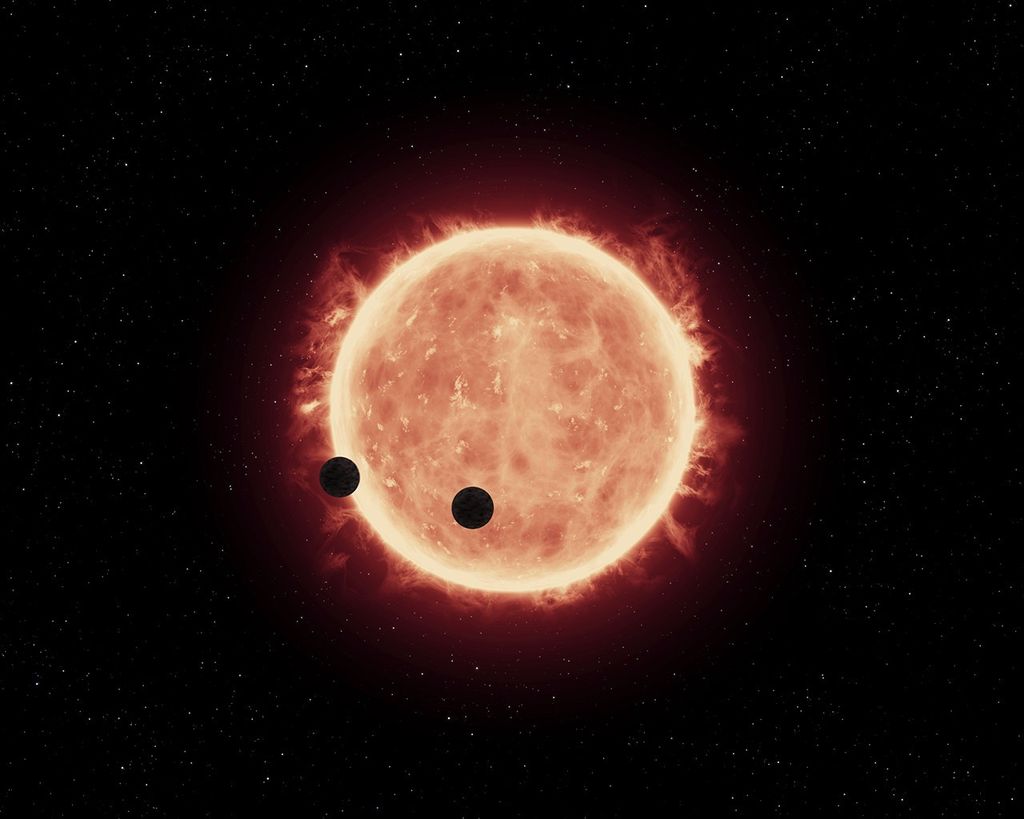

And for the MMPACT project, the Moon to Mars Planetary Autonomous Construction Technology Project (we call it MMPACT), we know that we’re going to need infrastructure on these different surfaces. We know that we’re going to need landing pads on the Moon, for example, because when an engine plume interacts with the lunar surface, it will actually start ejecting some of the material, and it can even eject it into orbit.

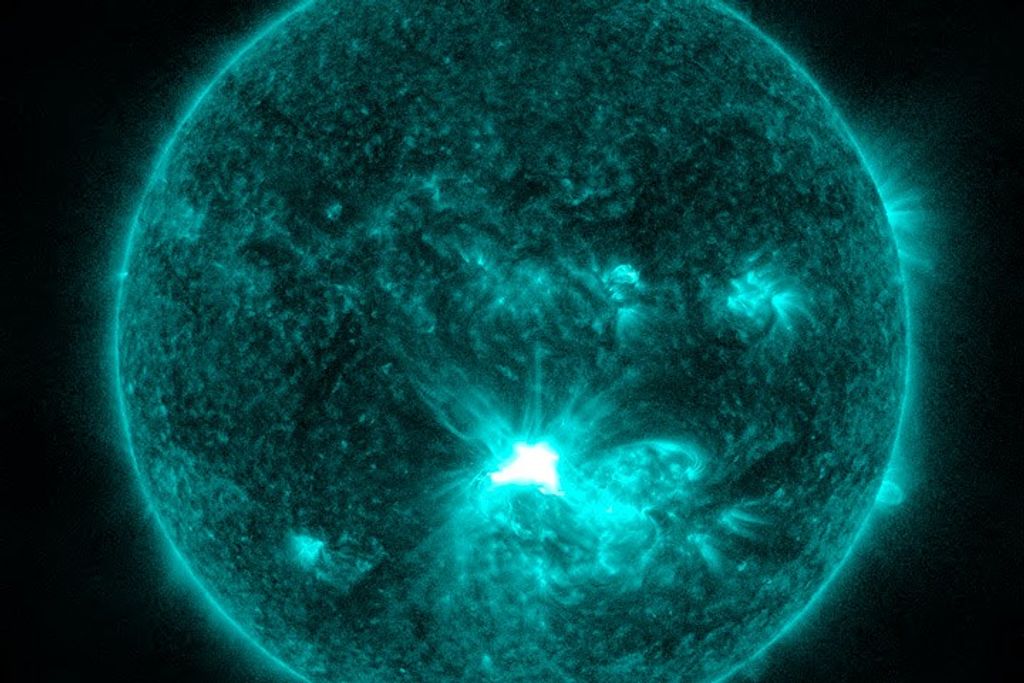

So, it creates quite a danger for surface assets, for orbital assets, and we know that we’re going to need things like landing pads, and we’re going to need roads and habitats and like lunar safe haven-type things. We’re going to need radiation shelters for solar storms and things like that. That was kind of the impetus behind MMPACT.

And if we’re going to enable the Moon to Mars architecture, we definitely need the facilities and the capabilities to meet that architecture, be able to test things on the lunar surface and then expand that to the Martian surface.

Host: You mentioned the possibility of ejecta being a hazard. Was that something that was measured during the Apollo era?

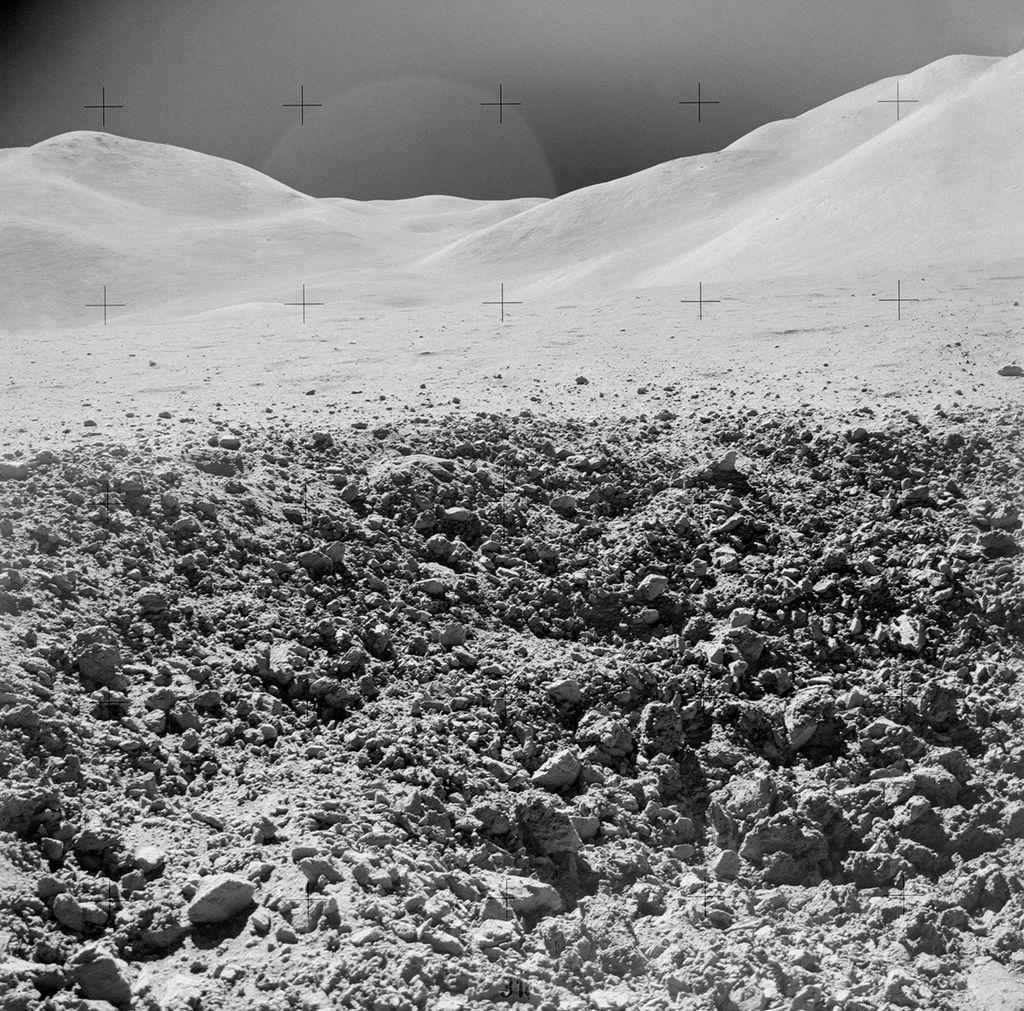

Dr. Edmunson: We do have some camera data that shows us parts of the material being ejected away from the engine plume as they were coming in for a landing. Since then, a lot of modeling has been done.

Phil Metzger is one of the people that has done that kind of modeling. He was KSC, is now UCF, actually. And he’s been fantastic with plume-surface interaction-type modeling. And he is the one that basically has shown us that the clouds that they saw during Apollo, and just all the things that we saw when we were there, are related to this plume-surface interaction, and how important it is, and how important that we have that mitigation for it, especially if we want to send landers to the same area over and over again.

And there’s another example from Apollo. They actually did an experiment where they landed Apollo 12 next to the Surveyor 3 spacecraft. It was like 1.2 kilometers away, something like that. But they noticed that the side that was facing the Apollo lander on the Surveyor craft was sandblasted. So, they, they brought back pieces of the lander, and they tested it, and it’s really shaped our understanding of the lunar regolith and plume-surface interaction and things like that today.

Host: Well, and that shows how important it was for those robotic missions to help humans know a little bit more, I guess, with Surveyor and then Apollo.

Dr. Edmunson: Absolutely.

Host: Yeah. How are regolith stimulants made, and what are the challenges in creating them?

Dr. Edmunson: So, terrestrial rocks and lunar rocks are very similar, and they’re very different.

On the Moon, we don’t have things like air and creating sand dunes and things like that. We don’t have water interaction, either. So, a lot of the processes that terrestrial rocks undergo is not seen on the Moon. We have basically impacts over billions of years, and we have day/night thermal swings that are just crazy. It actually starts tearing the rocks themselves apart. So, definitely some similarities, some differences.

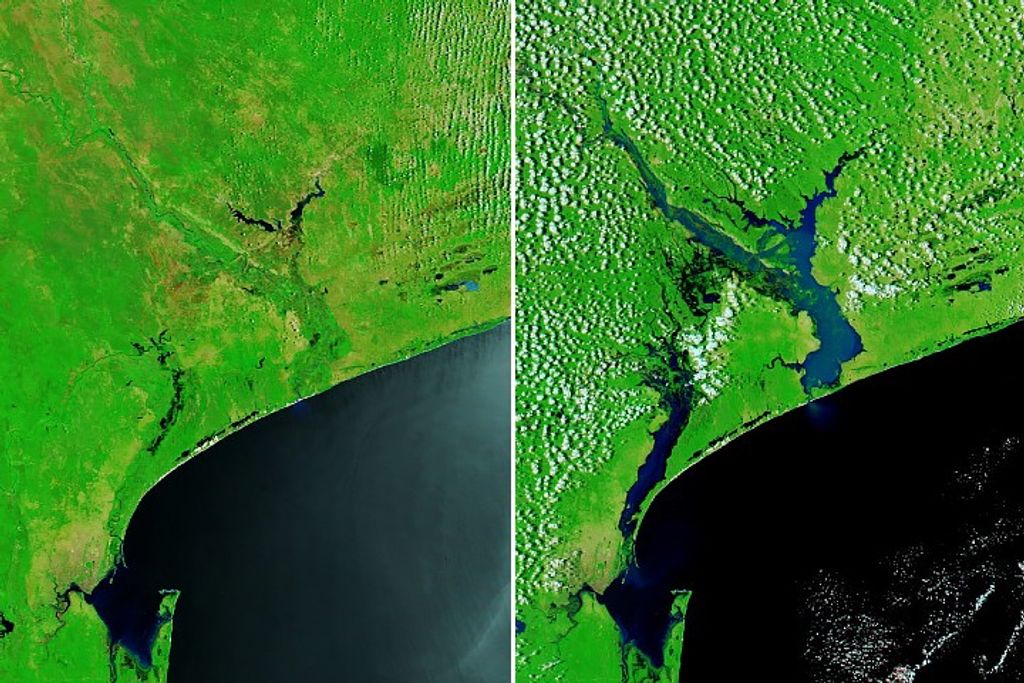

If we’re talking about Mars, Mars has a lot more water interaction, air interaction. So, you’ll see things like sand dunes, and you’ll see river deposits on Mars. So, actually, replicating Martian materials is easier for us on Earth than it is replicating lunar materials.

For the Moon, there’s materials up there that are geochemically, which means the chemistry of the material, is pretty similar to some basalts we have on Earth. It’s a rock type, volcanic essentially, like the Hawai’ian Islands and some cinder cones on various locations on Earth.

But, the highlands rocks, the lighter colored minerals, or the lighter colored material on the lunar surface, we don’t really have rocks that are similar to those. There’s, like, three different locations that are mineable materials, so we can get enough of those materials to start making simulants on Earth’s surface, and they’re not as high in calcium as we see on the lunar surface, either.

So, ideally, we’d be using a synthetic material to replicate the lunar materials. But it’s very expensive to make synthetic minerals and large quantities of them that we would use in in terrestrial experiments.

Host: You’re not trying to just get the chemical properties but the chemical properties, but the mechanical properties, as you mentioned before, right?.

Dr. Edmunson: Right. Milling and grinding and mixing: All of those are an art form. You can actually get a Ph.D. in one of those different fields.

There’s processing consistency. You have to make sure that the material is milled the way you want it to be milled all the time. And testing each batch is very important, because, you know, it’s a natural system. It can vary on the scale of a couple of inches, a couple of feet, it could be a couple of miles. I mean, it’s a natural system. They’re not homogenous.

So, testing each batch is, is so very important to making sure that you have a consistent material because we try to standardize simulants as much as we can and be able to predict their properties for, you know, the same tests over and over again, because we don’t want to have that variation that could potentially skew somebody’s testing results.

Host: And now that we have samples from Apollo, have there been unique differences in what we use maybe for Artemis training versus back in the ’60s for Apollo training?

Dr. Edmunson: So, we didn’t know a lot about the Moon when we went there for Apollo.

We did have some of the remote sensing landers and spacecraft, but it’s awesome that we now have actual lunar samples to hold because we know that there’s a lot more glass in the material than we originally expected there to be. We know what the consistency of the regolith is, the grain size distribution, the particle shape, those sorts of things. The density of it. The density was huge. And now we have better remote sensing data, as well. So, making simulants for Artemis is going to be a lot easier, a lot more effective than anything that we could have done with Apollo.

Host: Could you give some examples of systems or technologies that have been tested with the simulants?

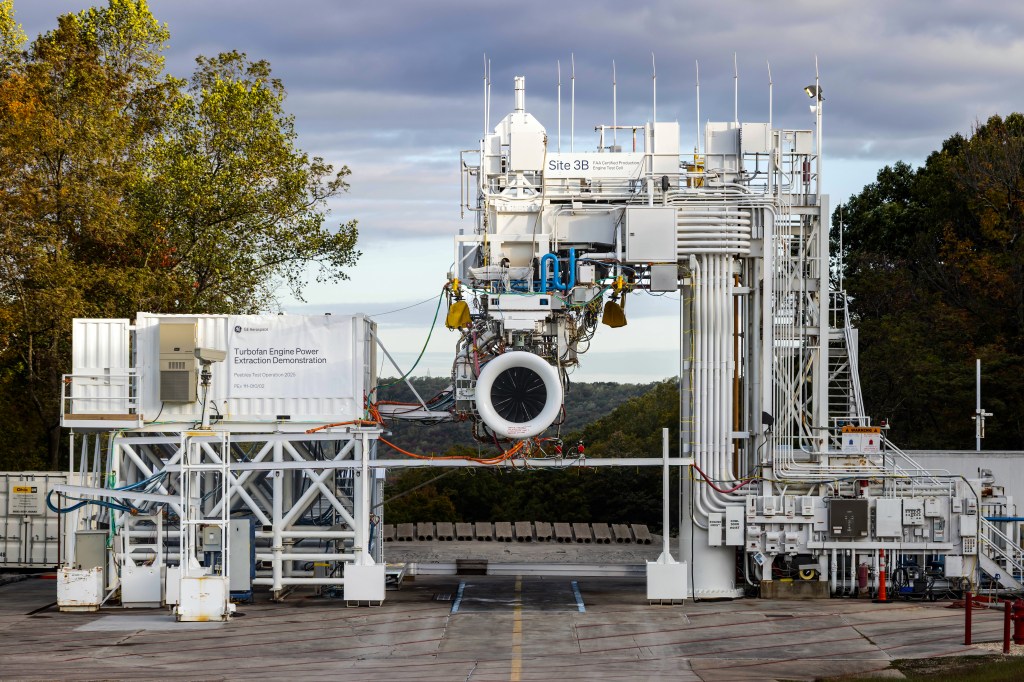

Dr. Edmunson: Sure. We test excavation technologies all the time. We’ve done in-situ resource utilization technologies like carbothermal reduction, molten regolith electrolysis.

We’ve also done construction technologies, like the MMPACT project, where we’re taking regolith simulant and we’re making it into construction materials. And then, of course, there’s always lander technologies and that plume-surface interaction. And how do the feet need to be designed to stabilize itself in regolith?

Host: It’s tough. It’s hard until you actually get there. We don’t have enough data just yet, but when we get there, I guess we’ll know a little bit more about how the regolith behaves and then iterate from there. Is that fair to say?

Dr. Edmunson: That’s fair, and the rock distribution as well. I mean, you don’t want to land your lander on a rock, or, you know, have it not at the right angle that it needs to be for takeoff. It’s so important.

Host: How does knowledge sharing work in your field? Are there different teams that are constantly just sharing results or ideas? How does that work?

Dr. Edmunson: So, at least in the lunar simulant community, we have the Simulant Advisory Committee, and that is a committee that has participants from all over the agency.

We meet bi-weekly to discuss the appropriate uses of simulants. We produce the Simulant Users Guide. We talk with simulant developers and simulant users to make sure that we capture the lessons learned. We make recommendations on best ways to produce the simulant materials, the kind of testing that you would need to almost (I don’t know, if “qualify” is the right word) a simulant. But there’s an important data set that we need from each of the simulant developers when the first starting out.

And we try to capture as much data as we can, because if one certain simulant doesn’t work well for one particular technology development effort, we want to find out why that is. Or, you know, is there something inherent in the process that we’re not understanding, and we need to make a different kind of recommendation down the road? We try to capture as much as we can (lessons learned).

Host: What about simulating Martian regolith for CHAPEA, CHAPEA being the Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog, where a crew of four simulates living on Mars for a year inside a habitat at Johnson Space Center. Do they also use Martian simulants, just for a little bit more realness?

Dr. Edmunson: So, they do have a little they call it the back porch or, you know, the outside of their CHAPEA building where they actually do have, I think it’s red colored sand because they didn’t want to use anything toxic. But they do have that and they do their little EVA activities out there.

Host: So, as a project manager, what are some lessons you’ve learned or would love to share with others?

Dr. Edmunson: Sure. Just be an enabler for your team. So, if they know what the target is and there’s a clear path to get there, just let them do it.

And if there are any kind of barriers, just help clear those barriers so the team can continue to work.

In terms of regolith simulants and things, lots of technology developers do not understand the difference between metal oxides and silicate minerals, and the vast majority of rocks on the Earth and the Moon are made of silicates. And Mars, of course, too, meaning that the major structure of those silicates is silicon and oxygen elements and a tetrahedra. So, that actually provides the structure behind the mineral. And you can’t just mix metal oxides together and create a simulant. It doesn’t work that way.

And related to that, sometimes the finest variables are the ones that make [the] biggest difference. So, it’s best to use the scientific method and just change one variable at a time.

Also, listen to your gut. If something doesn’t feel right, it probably isn’t.

Make sure that you trust your team to get the job done. And definitely it is okay to say, “I don’t know.”

Host: Could you share, perhaps, a lesson learned or a moment where maybe you had to pivot?

Dr. Edmunson: So, one of the things that we were looking at is during our construction materials development, we had to go from ambient conditions just out in the middle of a house or whatever, and take it into the lab. And it was not like a one-to-one kind of thing. The materials actually started degrading a little bit, and their material properties, because of being put into that vacuum.

So, we had to take a step back and look at the materials, look at how we were handling them, look at the processes that are almost exacerbated (I guess, is the right word) in a vacuum, and take a slower approach to developing the technologies. And we were not anticipating having so many issues when we got into a vacuum chamber, but it does happen.

So, that was kind of a huge thing for us. We had to pivot a little bit in terms of the way that we were developing this technology, because we were doing it for a custom environment in a vacuum.

Host: Learning as you go. So, Jennifer, how did you get to where you are and what was your giant leap?

Dr. Edmunson: Just being very tenacious, honestly, not giving up. You know, not everything works. Not everything is an economically viable solution. And don’t think that everybody is going to like your idea, because that’s not what they want to think is best; not everything is the best-case scenario. That’s kind of why it’s important to have multiple options.

Like, under MMPACT, we had a toolbox of materials, and some were more suited for things that were not the original target, which was the landing pad, but learning about those different materials and their different applications was really important in being able to enable other infrastructure elements like roads, habitats, those sorts of things.

And just don’t give up, because technology developments are hard, and sometimes they fail.

Host: And it takes a long time. Gotta be patient as well. Would you agree?

Dr. Edmunson: Patience is a virtue, absolutely.

[Laughter]

Host: Thank you so much. Jennifer. Thanks for sharing your insights.

Dr. Edmunson: Thank you for allowing me to. I appreciate it.

[Outro music]

Host: That wraps up another episode of Small Steps, Giant Leaps. For a full transcript of this episode, and to hear past episodes with fascinating people from across NASA, visit nasa.gov/podcast. While you’re there, you can also check out our other podcasts like Houston, We Have a Podcast, Curious Universe, and Universo curioso de la NASA. As always, thanks for listening.

Outro: This is an official NASA podcast.