The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

With its elite research engineers and world-class test facilities, NASA’s predecessor, the NACA, was the nation’s premier aeronautical research institution for over 40 years.

Overview

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) began in 1915 as an unpaid advisory committee which met periodically to coordinate U.S. aeronautical research but quickly evolved into an independent research institution with its own engineers and facilities. Over the next 20 years, its facilities, particularly its wind tunnels, became the nation’s premier aerodynamic tools. The NACA metamorphosed in the late 1930s and early 1940s into a multi-site organization with a broader scope of research, larger workforce, and more advanced facilities. It made substantial contributions to supersonic flight, jet propulsion, and improved flying qualities. Elements of its work manifest themselves in the 1960s space program. The NACA was disbanded in 1958 to become the foundation for the National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA).

Establishment of the Advisory Committee

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the U.S. government began focusing on the nation’s technological resources, including aeronautics. Up to this point, the government had largely viewed aviation as a diversion for private citizens and made only minor financial investments. Several European nations, however, saw the potential military applications and invested heavily in aircraft research and development in the years leading up to the war. It was reported that at the onset of World War I, France possessed 1,400 airplanes, Germany 1,000, Russia 800, with only 23 in the United States.

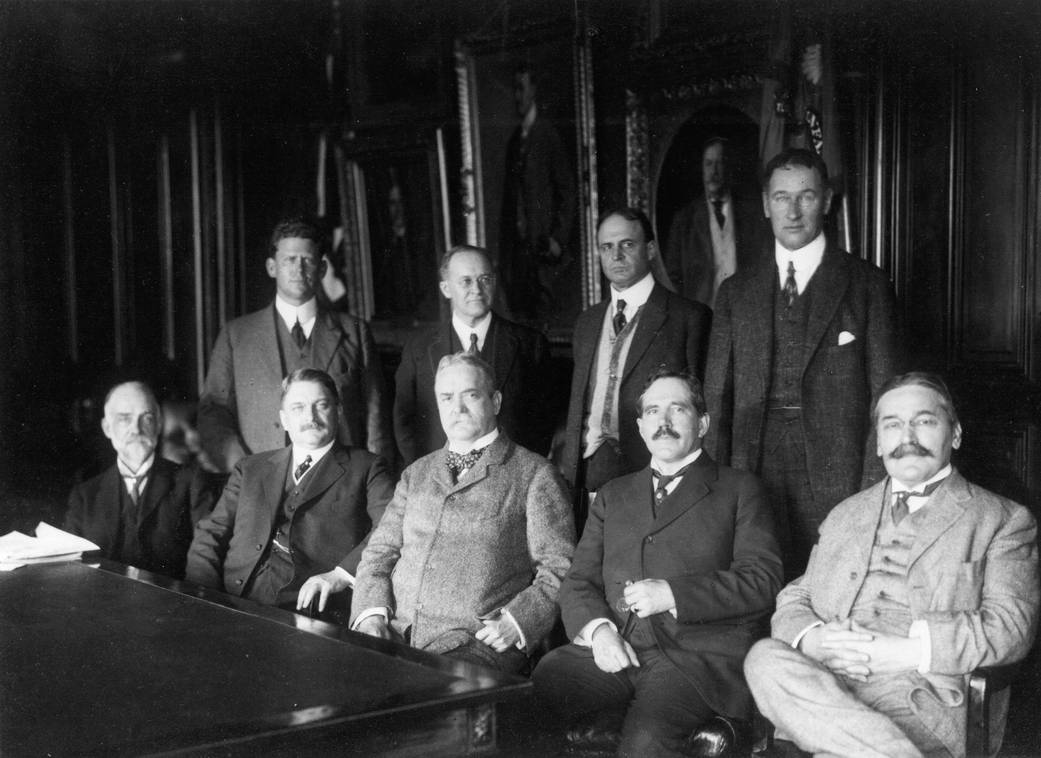

To rectify this situation, on March 3, 1915, Congress added a rider to Navy appropriation legislation that established the NACA. This 12-person advisory committee, consisting of appointed members from the military, government, and industry, initially met semiannually to identify key aeronautical problems and develop strategies to resolve them. The organization included Jerome Hunsaker as chairman, John Victory as secretary, and a seven-person Executive Committee pulled from the larger group. In 1919, George W. Lewis became the NACA’s Executive Officer and was later named Director of Aeronautical Research.

The NACA provided a forum where opinions from an array of stakeholders could be integrated for the common good. Representatives from individual companies were encouraged to work together to resolve problems too big for any single organization. To facilitate its work, the NACA established four major subcommittees with subject matter experts to oversee its primary fields of research–aerodynamics, propulsion, aircraft structures, and aircraft operating problems.

Langley Aeronautical Laboratory

During its initial years, the NACA had difficulty locating facilities to carry out its research work. Manufacturers were focused on current products and not interested in experimental designs or potential future aeronautical issues; and early attempts to convince universities that aeronautics was a legitimate engineering science were unsuccessful. The situation forced the advisory group to undertake its own research and engineering work.

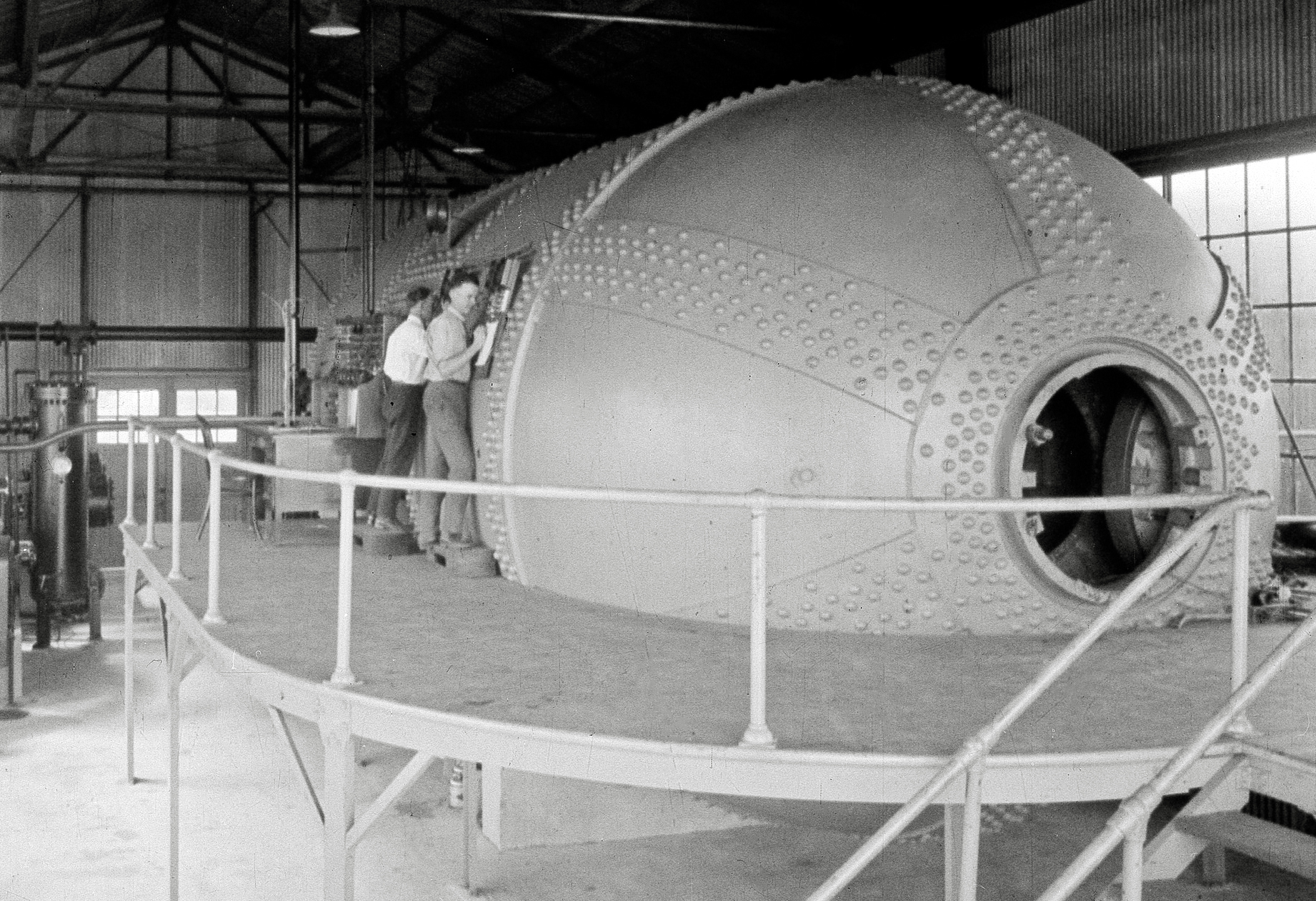

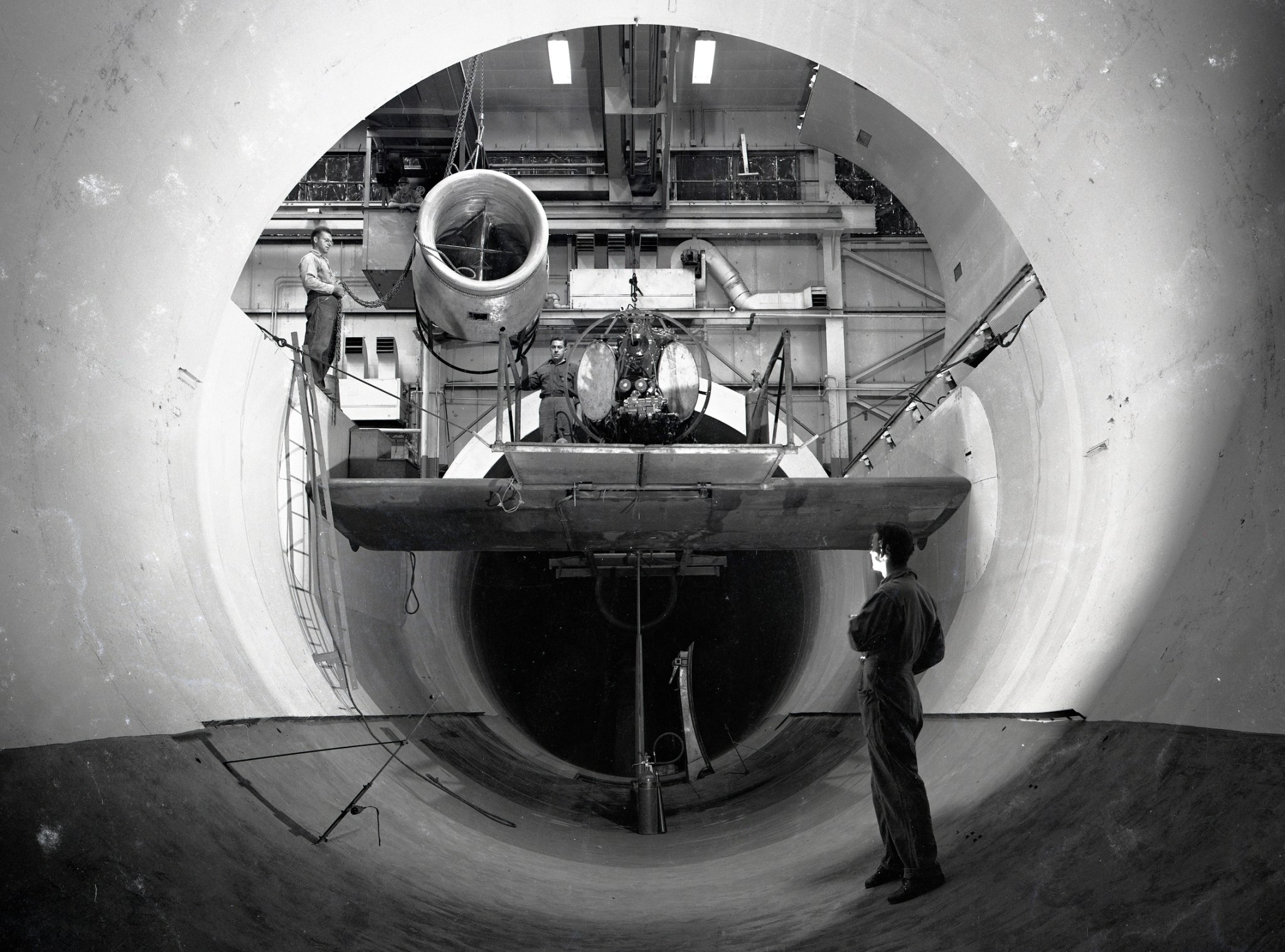

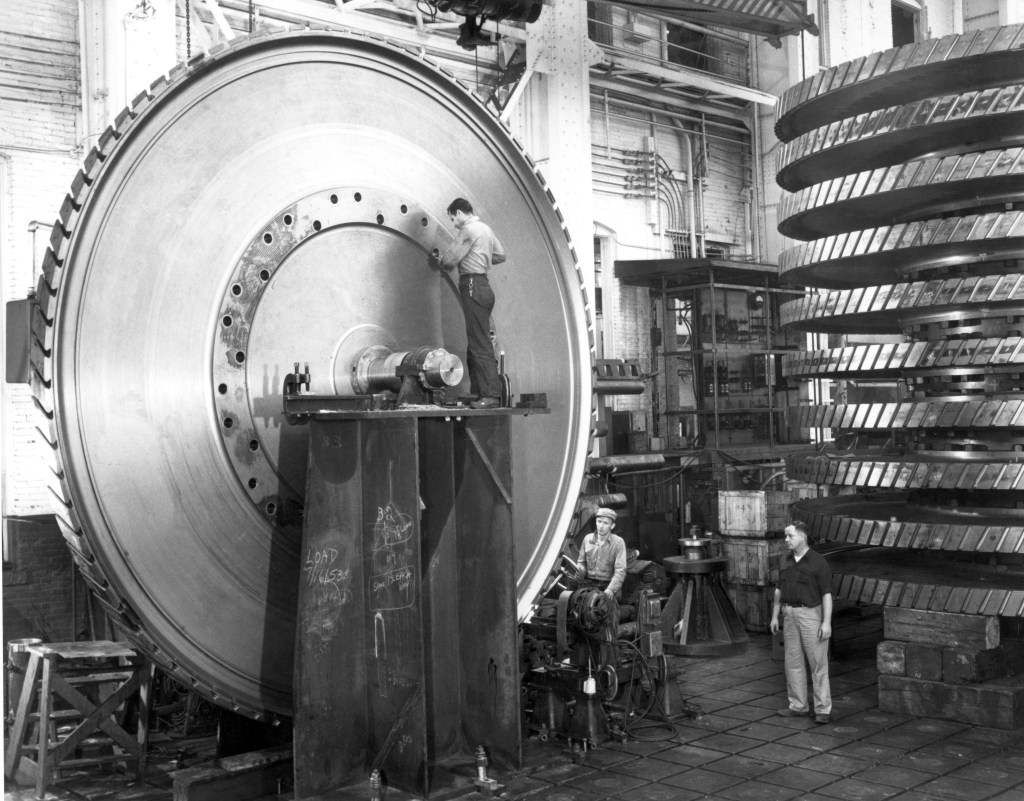

In 1917, the NACA began construction of its own research facility on a coastal tract of land in Virginia. It was initially a modest laboratory with a hangar, an engine test stand, shop, power plant, and office. John Victory immediately began the difficult process of finding aeronautical engineers to staff the facility. The Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory began operation in June 1920 with just four engineers, 11 technicians, and a rudimentary wind tunnel. By 1925, however, Langley had over 100 employees and the world’s first pressurized wind tunnel. The series of increasingly complex tunnels that came online in ensuing years was augmented by a steady stream of aircraft for flight testing.

NACA engineers made a series of key innovations, such as the NACA Cowl, that helped push the U.S. airline industry to prominence in the 1930s. With its limited budget, the NACA largely eschewed investment in the costly equipment and facilities required to study aircraft engines and focused on aerodynamics, where significant advances could be made more economically. The organization, however, did undertake intensive studies into aircraft operational problems such as stability, control, and icing.

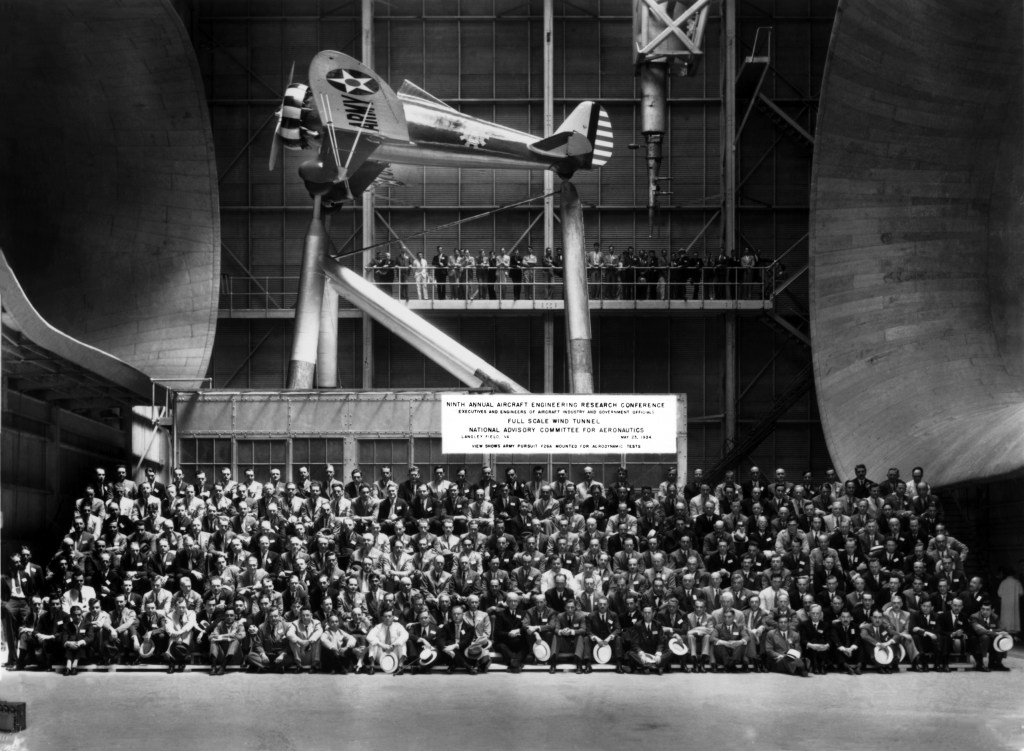

In 1926, the NACA hosted the first of its annual industry conferences in which dozens of guests were invited to Langley to hear about the latest research and tour the facilities. These meetings not only showcased the NACA’s contributions to aviation but provided industry representatives the opportunity to recommend future areas of research.

Expansion for War

In 1921, the NACA appointed J. Jay Ide to serve as the agency’s technical representative in Europe, where he documented foreign aviation and interfaced with European aeronautical research institutions. In the mid-1930s, Ide began reporting on advances such as new innovative wind tunnels in Germany. Subsequent tours of German aeronautical research facilities by NACA members Charles Lindberg and George Lewis confirmed Ide’s reports and revealed an emphasis on propulsion and preference for performance over quantity.

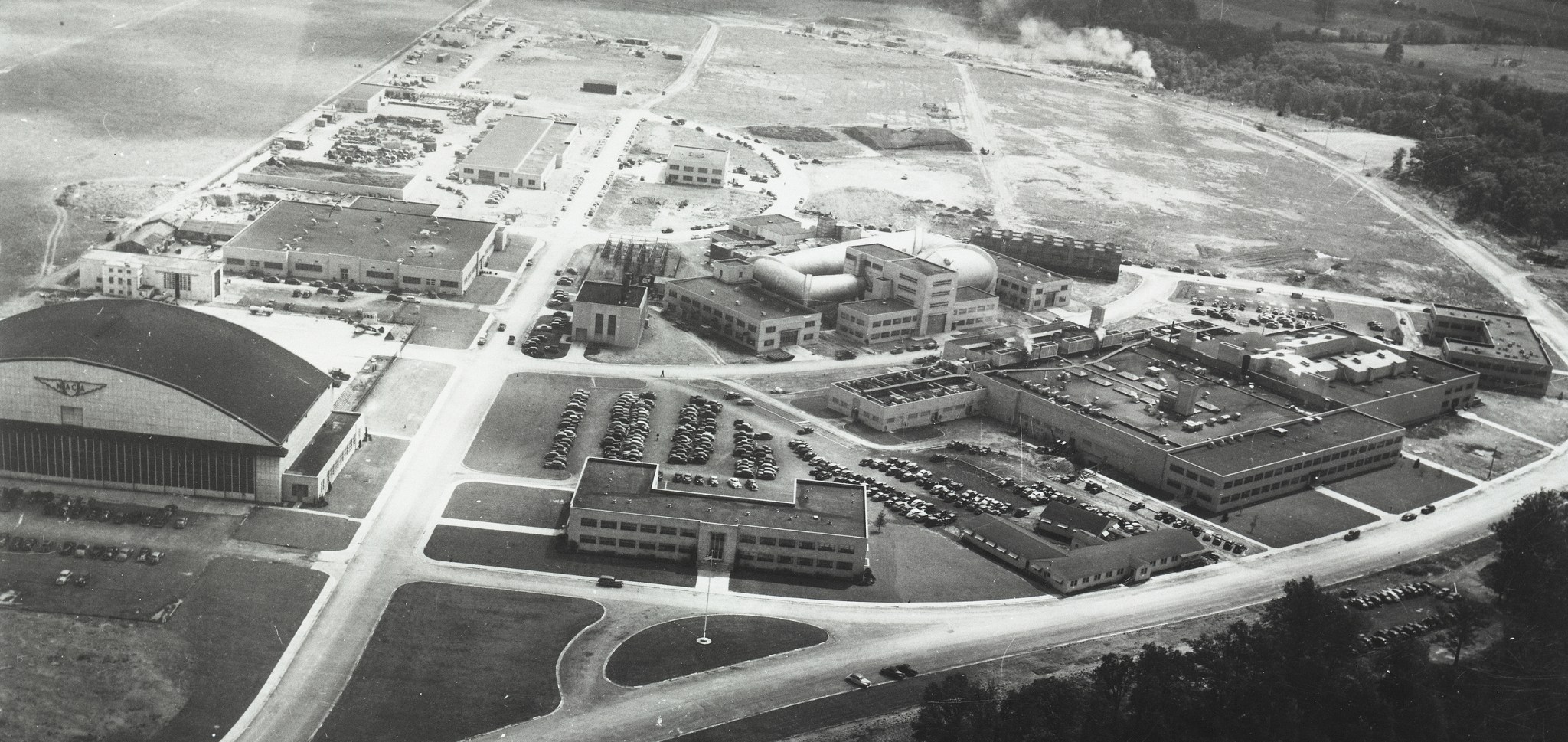

In late 1938, the NACA began planning for a new research laboratory to expand upon Langley’s capabilities. This was quickly followed by plans for a second new laboratory to be dedicated to engines. Congress approved the necessary funds and ground was broken for the Ames Aeronautical Laboratory (now known as Ames Research Center) in Sunnyvale, California in December 1939 and the Aircraft Engine Research Laboratory (today, NASA Glenn Research Center) in Cleveland, Ohio in January 1941.

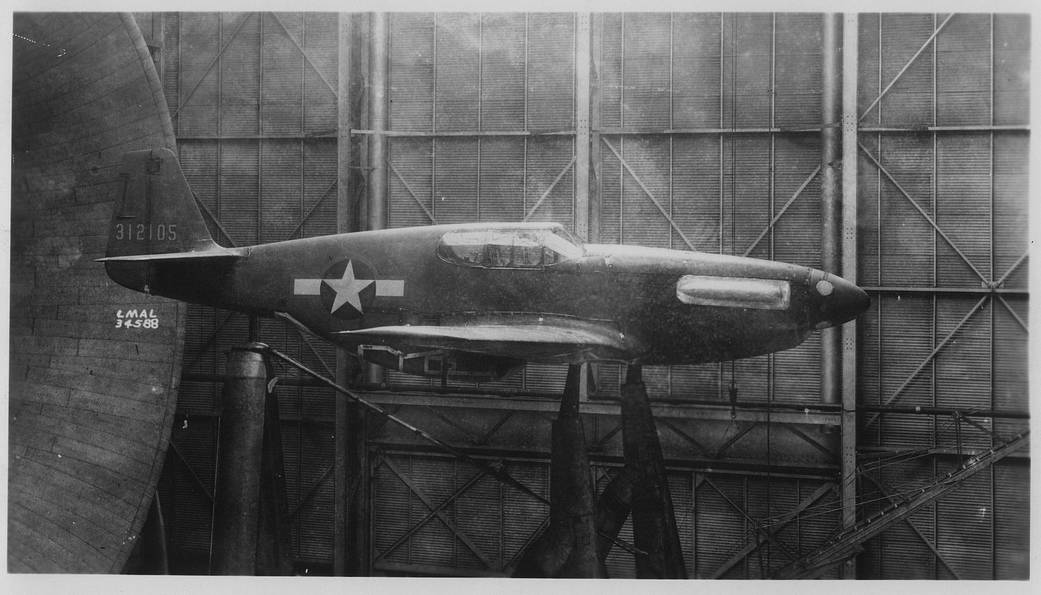

With the nation’s involvement in World War II, the NACA deferred most its research activities and focused on improving the performance of current military aircraft. The most well-known example was the systematic drag cleanup of fighter aircraft in Langley’s Full Scale Tunnel, but other important work was done on engine cooling, turbosuperchargers, duct rumbling, synthetic fuels, and icing. The NACA tested every type of U.S. military aircraft flown during the war, and air superiority proved to be a vital component of the Allied victory.

As new high-speed technologies emerged, however, the NACA found itself having to continue its efforts improving current aircraft while initiating experimental work on the turbojet and high-speed flight that would come to the forefront after the War.

Post-War Growth

The NACA emerged from World War II as a significantly larger organization. In addition to its two new research laboratories, it also added auxiliary facilities at Wallops Island, Virginia and Muroc Lake in California, and began construction of a third in 1956 at Plum Brook Station in Sandusky, Ohio. At its existing sites, a series of new, more advanced test facilities were built, including the Unitary Plan wind tunnels in the 1950s.

During the War years, the number of NACA employees grew from roughly 500 to over 7,000. Its annual appropriations increased from $1.26 million in 1938 to $78 million in 1957. The Executive Committee was expanded, and a host of new subcommittees were created. Hugh Dryden took over as Director of Aeronautical Research following George Lewis’ retirement in 1947. Dryden guided the NACA through its move into high-speed flight and the transition into NASA.

The NACA sought to return to its pre-War focus on fundamental research, while leaving development to industry, but the distinction between the two had become difficult to discern. In an effort to be more responsive to the aviation industry, the NACA formed an Industry Consulting Committee; reinvented its annual conferences as elaborate, multi-day Inspections which rotated from one laboratory to another each year; and introduced smaller, more focused technical conferences on specific topics.

New Realms of Research

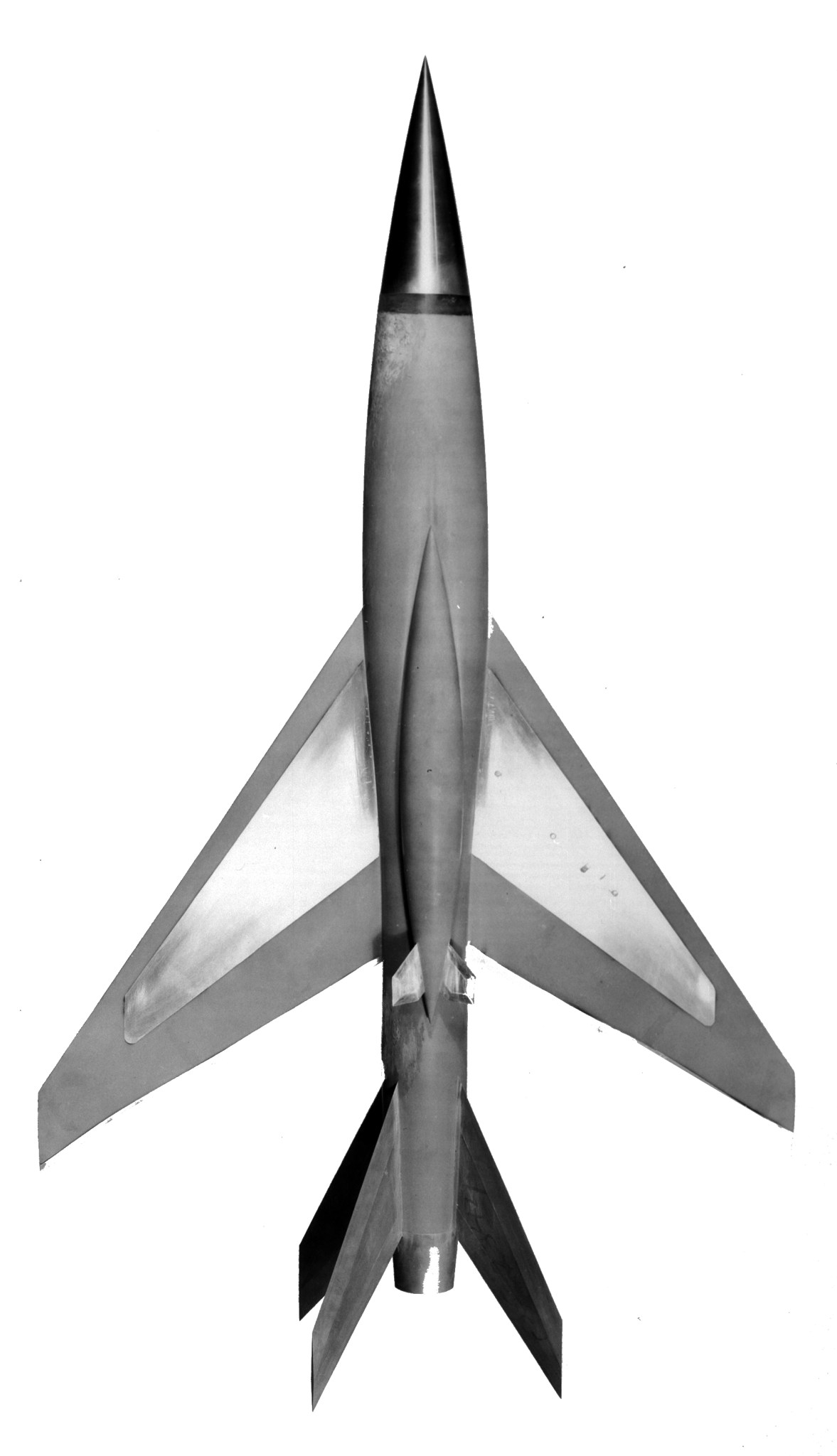

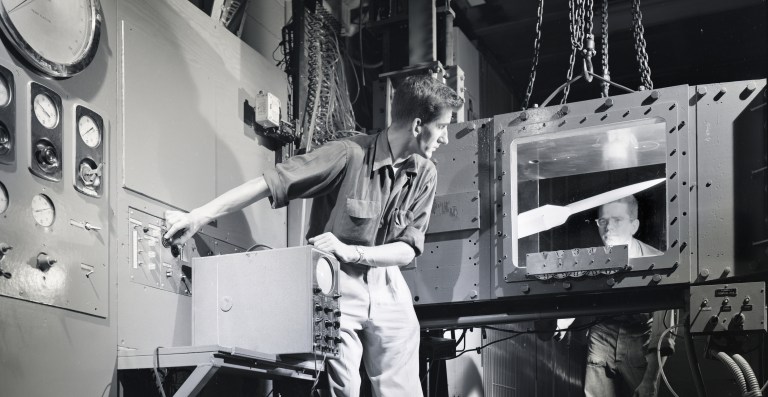

With some notable exceptions, such as icing research, the NACA focused on high-speed flight and jet propulsion in the post-War period. Langley engineers pioneered the swept-wing and area rule concepts. The former protected aircraft from shockwaves and improved efficiency at transonic and supersonic speeds. The latter, which indented the fuselage into a “Coke bottle” shape, facilitated supersonic flight. These concepts went on to be employed on nearly all supersonic fighters. Ames extended the work on the area rule and developed the advanced supersonic wing models that improved aircraft performance at supersonic speeds.

The Cleveland laboratory, which was renamed the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in 1948, concentrated nearly all of its resources on jet propulsion. Its researchers studied high-altitude combustion, thrust augmentation (including the first working afterburner), compressor and turbine design, and high-temperature materials. Nearly every type of U.S. jet engine underwent testing in simulated flight conditions at the laboratory during this period. Jet engine thrust increased from 1,600 pounds to over 10,000 pounds in just a few years.

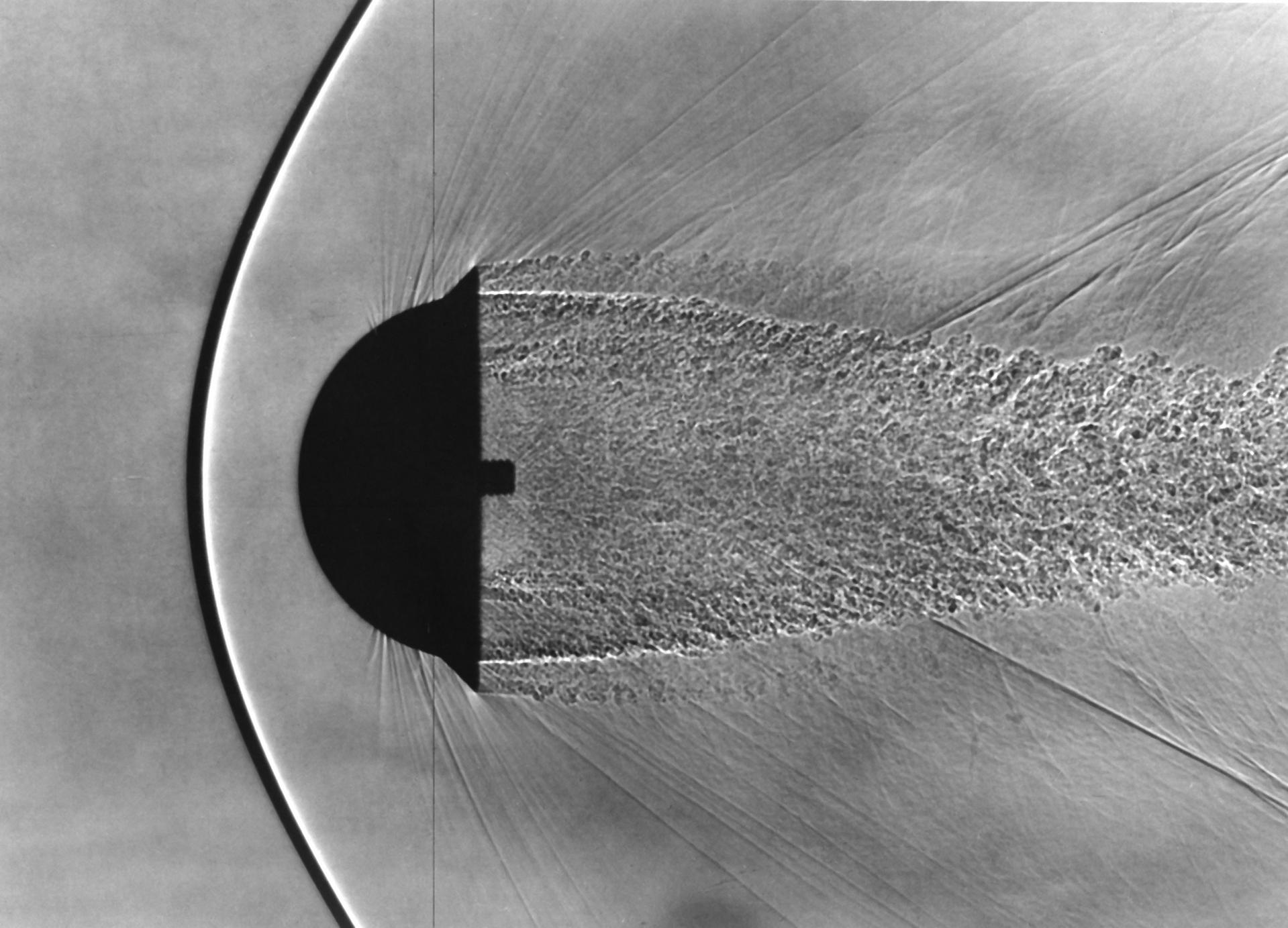

As the Cold War took hold, the NACA received additional national security funding which allowed it to embark upon on an unprecedented full-scale high-speed flight development program. At the time, little was known about conditions in the transonic realm. The Langley laboratory partnered with Bell Aircraft and the Air Force to design the first supersonic aircraft, the X-1. In 1946, the NACA established a small station (today, NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center) at the Muroc Army Air Field in California to perform the flight tests. On October 14, 1947, the Bell X-1 became the first aircraft to exceed the speed of sound. The supersonic research flights continued using D-558 Skystreaks and an evolving stable of X-planes to study high-speed dynamics and advanced design configurations.

Pushing Towards Space

For years, NACA leaders deemed space-related technologies outside of its mandate and considered missiles as weapons and thus falling under the purview of the military. Nonetheless, engineers at its three laboratories found ways to make forays into the field.

Researchers at the Lewis laboratory, who saw rocket engines as an extension of their aeropropulsion work, constructed a modest rocket test facility in 1945 to study combustion and cooling of JATO rockets. Soon, however, the group began concentrating on experimental high-energy liquid propellants. The lab’s identification of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen as the optimal combination in the mid-1950s led to its utilization by NASA’s upper-stage vehicles in the 1960s.

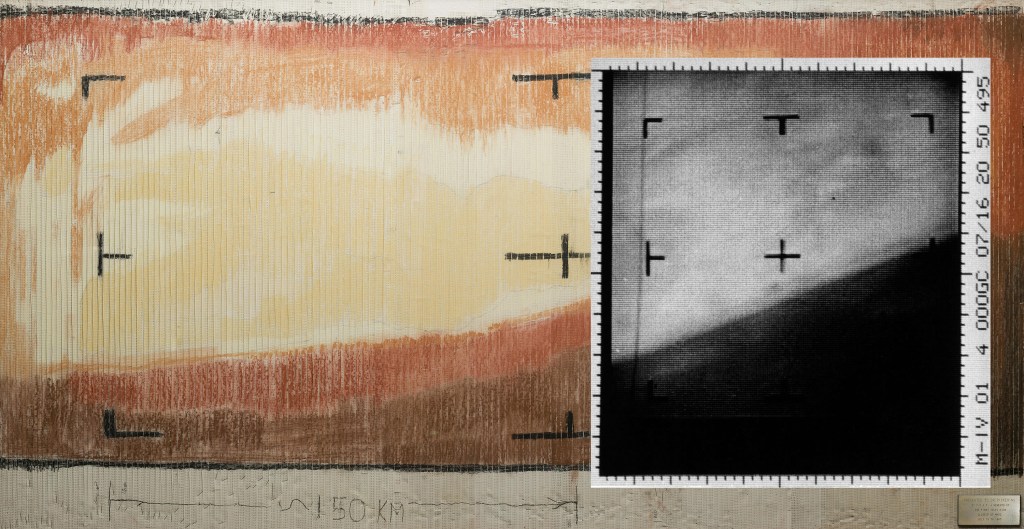

In the spring of 1945, Langley built the Pilotless Aircraft Research Station at Wallops Island. The test range provided a safe location to launch rocket-boosted free flying models in order to obtain aerodynamic data in the transonic and supersonic realms that was impossible to acquire in contemporary wind tunnels. A series of Mercury and Apollo vehicles were launched from Wallops in the 1960s.

In the early 1950s, NACA Ames aerodynamicist Harvey Allen began studying the thermodynamic aspects of atmospheric reentry. In direct contrast to existing military designs, Allen posited that reentry vehicles should employ a blunt nose to push the shock wave away from the body and thus significantly reduce vehicle heating. The blunt body theory was utilized on the capsules for the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs.

Transition to NASA

On October 3, 1957, NACA Secretary John Victory reviewed the presentations for the upcoming Inspection held at the Lewis laboratory. Victory ordered the speakers to remove any references to space flight from their talks. Following the launch of Sputnik the next day and an overnight increase in spaceflight interest, the content of the original presentations was restored.

As political leaders argued during the ensuing months over an appropriate response to the Soviet space achievements, the NACA underwent its own internal disputes over its role in a future space program. Some felt it should remain focused on aeronautics, while others considered space to be just a broadening of the organization’s legacy work.

Langley’s Robert Gilruth advocated for the NACA’s research on issues surrounding human spaceflight. In November 1957, the Lewis laboratory’s Bruce Lundin drafted a paper urging the NACA to lead the nation’s space program and proposed a new laboratory dedicated to spaceflight. The proposal was shared with Hugh Dryden and other NACA leaders on December 18, 1957, and was ultimately used as the basis for the NACA’s successful January 1958 bid to become the national space agency.

On April 2, 1958, President Eisenhower initiated legislation that would create a new civilian space agency with the NACA laboratories serving as its foundation. Dryden brought Gilruth, Abe Silverstein, George Low and others to Headquarters to establish a framework for NASA and its initial crewed mission, Project Mercury. In July 1958, Congress passed and President Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act into law. The NACA formally disbanded on October 1, 1958, and its laboratories became research centers for the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration.