From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

On episode 385, two NASA project managers discuss how astronauts will drive on the lunar surface during future Moon missions. This episode was recorded April 28, 2025.

Transcript

Nilufar Ramji

Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Episode 385, Commercial and International Lunar Rovers. I’m Nilufar Ramji, and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers and astronauts all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human space flight and beyond. We are going back to the moon, and this time, we are headed to the lunar South Pole, a cratered, rocky terrain where the sun is always on the horizon and sets every two weeks. As you can imagine, lighting conditions and the harsh environment of this geographical region on the moon can be tough to navigate. We need to be able to walk there, but given the distances we need to cover, we also need to be driving, both with and without spacesuits on the lunar surface. This is where lunar vehicles come to play. Astronauts will need a vehicle where they can live and work, and then another that they can use while driving from location to location while they perform moonwalks. So how do you drive on the moon? What capabilities do each of the different kinds of vehicles have to make them necessary to the mission with me, I have two experts, Steve Munday, Lunar Terrain Vehicle project manager and Danny Newswander, Pressurized Rover Project Manager, to walk us through how to drive on the moon. Start your engines.

Steve Danny, thank you so much for joining us on Houston We Have a Podcast today

Danny Newswander

You’re welcome to be here, glad to be here

Nilufar Ramji

Tell us a little bit about yourself. I want to know a little bit about your path to NASA and Steve, why don’t you kick us off?

Steve Munday

Okay, well, I’ve been here a few decades. I started as a co op. I know that’s that’s not the way things are done today, where people tend to jump around, but I came in as a NASA Co Op, and have been at Johnson Space Center for most of that time. So I’ve worked several programs and projects from x 38 you know, a space station crew rescue vehicle to Space Shuttle ascent gene and C to Space Station, even some early Orion when it was still called CEV. Let’s see. I was in Russia for a few years as part of the space station program, and then came back and did a series of tech dev projects, including Morpheus locks, methane, autonomous lunar lander prototype and BEM the Bigelow Expandable module, which is still on space station. Now we’ll ride it into the Pacific. Let’s see AMS Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, which is a cosmic ray tracking experiment up on space station. And then I got into landers, lander technologies, and that kind of led to being the JSC counterpart to the folks at Marshall leading the HLS. So I was leading the crew compartment, part of the HLS, the human landing system, and then finally moved over a couple years ago to the EHP, the EVA and human surface mobility program, leading up the lunar terrain vehicle, LTV, the the open Moon Rover, if you will. Yeah, the moon Jeep, not the moon RV, but the the one where they need spacesuits to hop on and off.

Nilufar Ramji

That’s fantastic. So you’ve done everything from sort of the earth, and now you’re headed to the moon, and then maybe one day, you’ll be looking at Mars.

Steve Munday

That’s that’s possible, slow transition. L is lunar, but there’s, but all of this is informing us about what might work for eventual Mars human Mars missions.

Nilufar Ramji

Fantastic, and I appreciate it. Appreciate you right off the top, because NASA is full of what I like to call alphabet soup. You spelled out every single one of the acronyms you just did. So fantastic. Danny, why don’t we hear from you?

Danny Newswander

Oh well, my experience is a little different than his. I’m what you call I think at NASA they called him early fresh outs. You pretty much. I did not go through a Co Op program. I was at university studying getting a bachelor’s in mechanical engineering. Happened to be doing thermal analysis on a small satellite project that aligned with what NASA’s engineering needed at the time. And so I was pretty much no Co Op, no time for training or get situational awareness. They brought me straight in and said, Here’s your job. Go for it started out. I’ve haven’t been here quite as long as Steve, but pretty close to it. Started off as an analyst at thermal analysis testing started early in my career, working a lot with the Japanese most of it had to do with making sure that their vehicles that they were doing for Space Station aligned from a thermal perspective, did that for a while, then got into project management, did some projects with the Japanese utilizing the ISS, the International Space Station. From there, eventually transitioned over to the ISS program helped the Japanese develop and continue to operate their cargo vehicles for the International Space Station, the h2 Transfer Vehicle, which is commonly called the HTV, they have a new one that’s coming online, I believe it launched later this year, called the HTVX, which is kind of their second generation of that cargo vehicle, that one eventually is going To go to Gateway. And so there’s a lot of technology development, things they’re putting into place to do. So from there, came over to work, to pressurize rover with JAXA, with the Japanese as well. So that’s kind of how I’ve navigated through NASA, yeah.

Nilufar Ramji

So great relationships with the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, which is fantastic. So this, this naturally makes sense, but both of you guys touched on EHP, extra vehicular activity in human surface mobility program. So what exactly is human surface mobility, since I started with Steve before I’m gonna go to you Danny

Danny Newswander

ask me. So yeah, it’s, it’s, I think it’s kind of a mouthful to just say we want to be able to take the astronauts farther away from the landing spacecraft than they would be able to do on their own with just EVAs or space walks. So these are two capabilities that you traverse drive whatever mobility type term you want to use to different places on the lunar surface to, in essence, be able to take your astronauts farther away from their landing site than they would be from a space walk, so that they can do science technology development, pretty much enhance science exploration, if you will.

Steve Munday

Yeah view the EHP is a long mouth full, which is why we say EHP, right, not the full name that you just said very well, a lot of people can’t remember it, but if they’d asked me, I would have called it suits and rubbers. But nobody asked

Danny Newswander

You would have probably called it rovers and suits.

Steve Munday

Well, I would have reversed it clearly, but the the Apollo program showed us the multiplying effect, the leveraging effect of rovers. Yeah, the first three missions were all walking in suits. So 11, 12, and 14, no rover. Then you had a rover. LRV for the last three missions, 15, 16, 17, and the number of samples that they got in those last three missions with a rover tripled the number of samples they got those first three missions. So it’s not just you can go further. You can do more. You can bring back more. You can all more. You got a truck, you know exactly.

Nilufar Ramji

exactly

Danny Newswander

I have something I’d like to add, if that’s okay. So my role is kind of a unique role in this situation. We might get into it more when we talk just kind of the relationships with the different providers is, I don’t have contracts, or we don’t have contracts, or anything that we work with with the Japanese it’s, it’s kind of a mutual partnership. They’ve come forward and said, Hey, is there part of the Artemis enterprise? They want to contribute a pressurized rover, and then my role is to, in essence, assemble a team, build a culture that works in partnership with them to make sure that this pressurized rover that they’re providing to the Artemis enterprise meets a few things. One is, it gets to the moon, which happens to be, you know, one of our most challenging aspects right now is, how do you take something this capable, this big, if you will, and get it to the moon, given the considerations you have on just the challenges you have on getting stuff to the lunar surface, but also that it’s safe for crew members. As Steve mentioned, you know, you know, he’s working with just the space suits. I work with crew members. We work with crew members in a shirt safe environment, but also in a space suit environment as well. And then the third thing is that you can enhance science utilization technology development, not only from a crewed perspective, but also when you’re in your uncrewed phase, which happens to be 90, 92% of it the life of this pressurized vehicle. So my role is pretty much coming in, building a team, building a culture, so we can work in partnership with Japan, because we don’t have any contracts in place that we can leverage to help them build the right rover for the Artemis enterprise.

Nilufar Ramji

That makes a lot of sense. And for our listeners, when we’re talking about the Artemis enterprise publicly, we call them the Artemis accords. So this is where we have international cooperation with over 50 countries, I believe, right now and counting, that have agreed to explore the moon and beyond together. So this is the Japanese contribution among many others,

Danny Newswander

among many others. This is their first one that we’re working with him

Nilufar Ramji

Fantastic and so to counter that, Steve, I feel like you’re a little bit different. Your world is a little bit different when it comes to the relationships and contracts.

Steve Munday

It is different. Danny is unique in that he has to be a diplomat. He is working with the Japanese. He’s fluent in Japanese, if you want to speak Japanese. So he’s kind of the perfect PM, for pressurized rover. I don’t have to be as diplomatic as Danny,

Danny Newswander

but I will say you are. You don’t have to be, but you are even more so.

Steve Munday

Thank you. I’ll take that, but I have to very much focus on the commercial side. All three of our contractors we have right now have big commercial plans because, as Danny pointed out, most of the time, this thing is not crewed, and in our standard missions that we’ll have in the last the operational phase of our contract, NASA will buy a certain number of months from them, but then the rest of The time they’re they’re free to commercialize as they can so that means commercial provider to payloads. That means advertisers. We’re going to see some very interesting things, I think, from whoever is selected to take their LTV all the way to the moon,

Nilufar Ramji

taking lunar exploration to the next era of space exploration.

Steve Munday

Right, right. Commercial. The commercial side is a huge focus of the LTVS contract, because we really want to help ignite or foment lunar economy. So this is part of it, like we’ll be your anchor tenant LTVS providers, but you need to go find other customers and

Danny Newswander

well And along those lines, even though our jobs, our roles, are kind of different, I think there’s a lot of similarities in the sense that Steve and I are both trying to take exploration to that next step. He’s working on the commercial sector. I’m working on the international sector. But at the end of the day, for us to do a lot of the things we want to do, it’s going to take both sectors working in tandem together. And so really, when you look at it, we both have to be kind of like diplomats, where we’re working in these different environments, even though there there’s some dissimilarities between the two. But really it comes down to our job is to build NASA teams. Build a NASA culture. Build a culture between the providers and NASA that allows us to be successful in both of those arenas.

Nilufar Ramji

That’s a great segue to a question that I have for you, Steve, tell us a little bit about lunar terrain vehicles. You, you said LTVS, you talked about different providers. Just walk us through a little bit of where we are in this process right now with lunar terrain vehicles.

Steve Munday

Okay, since I joined the project as a PM, a couple years ago, released RFP for the Lunar Terrain Vehicle services contract, LTVS and the S is important. You got to remember it as a services contract, the provider will be on the hook to deliver. That means they got to go find their launcher, they got to go find their lander, and we just buy the service once it gets there. So we never take ownership of the vehicle. The vehicles are always theirs. We provided in the RFP a set of higher level functional requirements, and that that’s the part that has been one of the challenges of getting people comfortable with that kind of approach, where we’re not telling you how to design every component and spec up your subsystems. We’re defined. Here are the higher level functions we need, and now you figure out how to go meet those functional requirements, how to go deliver the service that we need. And the amazing thing is, if you look at our three providers and their concepts, they are very different, which is exactly what we wanted, in a way, right? We wanted innovation. We found three providers that came up with three very different rovers, three very different solutions for the same requirement. So it’ll be we’re going into, well, we’re nearing the end of our phase one part of the contract. So on May 20 of the last year, we got ATP backing up, let’s say March, April, we did the selection. We got three. We were very happy to get that, because there was no guarantee we were going to get even two, much less three. So we’re very happy we’re able to afford three. I’ll attribute that to the power. Competition, we got three, you know, reasonably priced providers that enabled us to select three. That’s been a challenge then over last year to provide insight and support all three contractors. Certainly, our team has been well stretched covering all three, but it’s been exciting to have all three and have three very different solutions, three different very different vendors in three parts of the country responding to that, and they’re all coming to the end of this phase one, which gets them to the preliminary design review level. So preliminary design means you’ve taken your concept to perhaps a 10% that’s a rule of thumb people throw out for PDR, 10% level, meaning your overall design has closed. You’ve closed the mass. You’ve closed overall how the systems are going to work. And now the next phase will take you to a critical design where you get into the details of how all those subsystems are going to work, both for the rover and again, for the delivery systems, the launcher lander. One of the one of the communications I’ve been, you know, repeating early and often to whoever will listen as though we plan to down select to one for the demonstration mission task order. We would love to have two we’ve seen, obviously, from other programs, even recently, the advantages of having two for backup purposes, but also to continue the competition that we’ve seen so much of in this first phase. So my phrase has been two for two going into the selection, we would love to have two for two. That’s obviously a budget decision, so we won’t know till we get to the down select.

Nilufar Ramji

That’s very exciting. And I think that there is a lot more ahead for LTV, and I’m interested to see what kind of additional industry is developed as a result of these innovative designs, despite only one being selected. Before we talk a little bit more about LTV, I just want Danny high level. Can you tell me what is the pressurized rover?

Danny Newswander

So it’s kind of, in its name. It’s pressurized, right? It’s, it’s, in essence, a mobile habitat where the crew members can drive in a pressurized environment. They can live in a pressurized environment, eat, sleep, drive, do other work, talk to their families, things of that nature in a shirt sleeve type environment. It also has the capability for them to do space walks out of it. So when they get to whatever location that the NASA community, the international science community, has determined is a value to go to, they can put on their space suits, depressurize the pressurize rover, and go out and go on a space walk. So that’s what I think most people think about, is this kind of pressurized vehicle that the crew can drive around and kind of like you see them, the astronauts in the International Space Station, but then also has the capability to go off and do space walks. Now it’s easy to just think of the vehicle in that nature, but like I mentioned, 10, 8% of its life is in that crewed type configuration. The remainder of the time it’s in an uncrewed configuration. It also needs to have the ability to get from launch, well, landing site to landing site. So, you know, they can drop off the crew, and eventually, when the next crew comes, they can go pick up the next crew. So it has to have this ability to operate in an uncrewed way. And so there’s a lot that’s going into how does it navigate the lunar surface on its own, autonomously or from a ground controlled configuration? And so when, when I think of it, I try to think of it, it, is it? The most important thing is it keeps the crew safe. But when you start looking into we’ve got to really focus on both of those paradigms, the crewed and the uncrewed portion, and try to enhance utilization, science technology development through both times. But big picture, it’s a pressurized vehicle that can move about the lunar surface and allows crew members to do space walks in the interim, it’s going to be utilized for uncrewed science, uncrewed utilization, and then it also needs to be able to traverse so it can it can get to each new location in the time the crew is not there.

Nilufar Ramji

So let me see if I can break this down for you. Lunar train vehicle driven by astronauts can operate autonomously. Require spacesuits. Pressurized Rover driven by astronauts can operate autonomously, but does not can be a space where you live and work does not require spacesuits. Is that a good way to explain it? Break it Down?

Danny Newswander

she’s working this out of a job here,

Steve Munday

You know when you drive down the highway and you see an RV,

Danny Newswander

yeah, that’s how I keep thinking about it I guess, well, and that’s one way to look at it. I know one of the questions you might bring up is, how do they work together? Do they work together? Why do you need both, right? But there’s different approaches to doing that. One is kind of what Steve’s pulling on. You’ve got your RV and you’ve got your jeep with the ducks in the right, right? We should have ducks. You should have ducks, yes. But that way, if they work together, you know, the LTV is going to be a lot more nimble. I don’t know if that’s the right word to use. It’s going to be able to go places. The pressurized rovers not going to or you’re not going to want to take the pressurized rover for various reasons,

Steve Munday

more of a hardcore all terrain vehicle. You can hop on and off. You know, look at that rock. Let’s go grab that much more easily because you’re already in the suit. Right, right, right. The flip side of that is you’re limited by the duration that you have in the suit. So you’re only on that LTV, as long as that suit, you know, as an astronaut, as long as the suit will allow you before you got to go back into the lander or the PR

Danny Newswander

and so that’s why, you know that example is used a lot, a Jeep RV type thing. But there will be times they need to be separate and do things independent,

Steve Munday

Sure they will back once they’re you know, the LTV is going to come first couple missions before PR, but once they’re both on there, there will be joint CONOPS. They’ll support and complement each other.

Nilufar Ramji

I can’t wait for that time. And that takes me to my next question, which is a little bit more about the history of using rovers on the moon. So you touched a little bit on it with the different Apollo mentions. So why are lunar terrain vehicles so important for the agency’s Artemis campaign?

Steve Munday

Yeah, like I mentioned, it is just a multiplier. It’s a leverager. It can take you farther. It can let you do more science. This is a heavily science focused vehicle. Both are but yeah, as we pointed out, astronauts are there for a little bit of time. Most of the time. You’re autonomous or tele operated from the earth, and you’re doing science, science with a robotic arm. So think of it like a Mars rover. In fact, in LTV, we often call it LTV in equation form, because we’re engineers, LTV equals open bracket, Apollo rover plus bars rover closed bracket times commerce.

Danny Newswander

So it’s we have not done that yet on the press release oversight, you don’t have your vision equation

Steve Munday

yeah. So we have all the features of both Apollo and Mars rovers, but multiplied amplified by the power of commercialization. So I want to point out, going back to Apollo again, if you go, if you go read across the airless wild, I’ll go an unsolicited plug for a book that I recommend to everyone who’s who’s thinking about rovers on the moon. It goes through the history of LRV lunar rovering the vehicle for Apollo, but in the initial days, you know, von Braun and company, they, they had much bigger plan for what LRV was going to it was going to be a they had something called a Moab. And anyway, their initial concepts were basically what we’re going to get now at the PR, it was a six wheeled pressurized vehicle that would require another Saturn five to launch a land so I think that’s kind of where they ran into the budget and well,

Danny Newswander

and that’s a great point. People tend to think, hey, here’s a pressurized rover, it’s new, right? Or, here’s an LTV, it’s new. We’re just building off, you know, standing on the shoulders of giants that have come before us, right? Japan, the same way, Japan has been working on the pressurized rover for, I don’t know, 20 years, as far as 2030, years, as far as the ideas and the concepts I know. We go all the way back to Apollo, and we’re just trying to learn from the past and look at the current environment and the current challenges and figure out how to how to take that next step. And the same time, both Steve and I realized, when you talking about Mars, that there’s going to be team members, NASA folks, international entities, that are going to come forward and take whatever we end up with and take it to that next step, and take it, take it further. And so that’s one reasons it’s so important we’re trying to build the right cultures and the right teams. Is because Steve and I both realize we’ve both been here a few decades. As you put it, would love to be here a few more. But you know, life moves on, and at some time it’s gonna there’s gonna be those next, that next generation taking that step.

Steve Munday

So earlier, early Apollo one to do PR, budget and schedule. Realities stepped in, and it came down to, okay, what can you squeeze into that quadrant of the the set stage of the lunar module? We’re not going to be as light as that. I think that was only, like 200 kilograms or something. The LRV that’s in your seats, right?

Steve Munday

Exactly. We won’t be that lightweight. We’ll be larger and heavier than that. But it’s more that idea, the the LTV is the the lighter weight, open, hop on and off. You know, science, uh, exploration of opportunity, opportunistic science, exploration, I think that’s the term they use.

Nilufar Ramji

I have so many questions, So I guess I could ask both of you guys, what are the advantages for NASA using this type of a. Approach with international partners, with you, Danny, and with commercial partners, with you, Steve. And I don’t even think we call them partners. We call them contractors or vendors.

Steve Munday

Contractors, yeah, I think we were schooled on that early on. Don’t call them partners. Call them contractors,

Danny Newswander

yeah. And I’m in the other boat where I don’t call them contractors. To me, they’re providers or partners. It’s

Nilufar Ramji

all based on the type of procurement you have here at the government.

Steve Munday

Yeah, Danny’s are absolutely partners, international partners. Yeah, for so, cost. By giving, we are firm fixed price contract, that is, they put in a price, and they can’t go over that price, so they had to build that into their proposals. From the get go, they have to their proposals included Knowing this first year of feasibility and preliminary design, and then the next four years of actual development to a demonstration on the moon. But also the 10 years after that, of services where they have to provide services to Artemis for 10 years for either one or up to them or multiple. You know, we don’t care how many LTVs they put on the surface, it’s provide the service. So they had to build in all that risk into their proposals. And they’re not to exceed numbers into numbers, because it’s firm fixed price. It’s different than the old school cost. Plus was like, well, we want a little more. We’ll pay a little more. And you know, it’s like, nope, yeah, you got a cap. Provide that service. So they had to build in all that risk up front, which is hard to estimate where they going to be in 15 years when they were proposing this. And what, what commercial partnerships can they, you know, depend on, you know, they probably at the letters of intent level right now, for those commercial partners, nobody’s going to sign up until they actually win the thing. So a lot of risk built in. So it’s kind of amazing that given all the risk of this, you know, 15 year performance period, that we were able to get, able to get three that we could ex afford for the first phase, and then hope to get at least one for the for the next phase, to actually develop it. So cost is a big advantage. The competitive, the competition, like I said, has given us three innovative, very different solutions, all meeting the same requirements. And again, long term, the lunar economy, they’ve all got great commercial plans, and it’s been pretty interesting and amazing to see all the out of box thinking that’s going on into it’s not just University and other space agencies providing scientific payloads for them, but it’s you’ll be surprised to see what they put on the moon. As far as innovative commercial partners in advertising that sector

Nilufar Ramji

It’s very exciting to see, and it really does make space accessible. Danny, I’m going to get to you in just a second. I have a follow up question for you, Steve, what kind of you keep talking about the three providers? So I think it’s worthwhile mentioning who the three providers are, and when you’re mentioning that, I would like also to ask you, what’s one thing that’s different about their What’s the thing that stands out? Maybe it could be that they’re standing instead of sitting.

Steve Munday

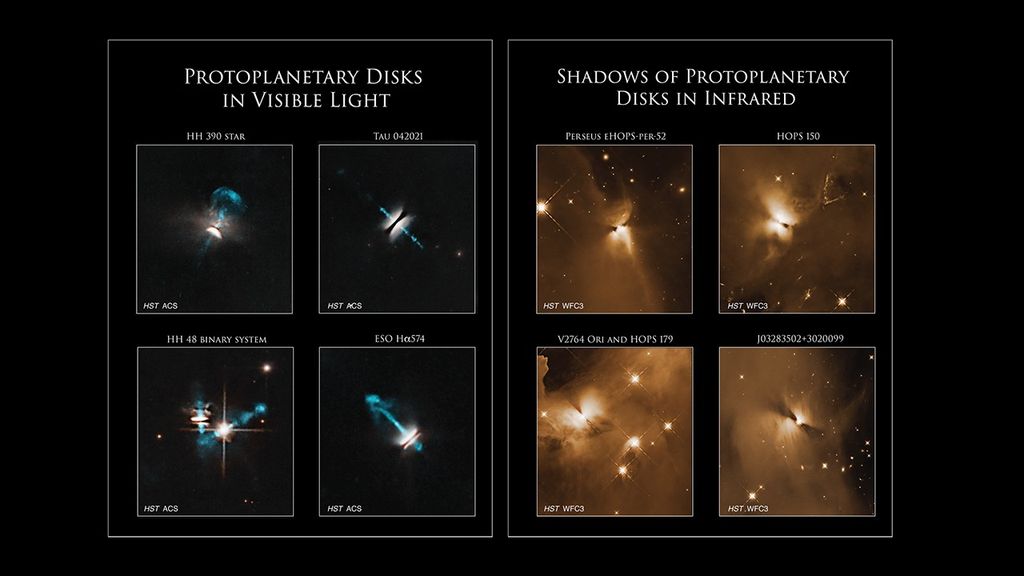

Okay, so, all right, and no particular, no, I’ll go geographically west to east. So going west to east, we’ll start with jury astrolab, or just astrolab in Hawthorne, California, right next to SpaceX. So let’s call them the LA group. They, they came in with a design that was a, almost like a supercharged Mars rover. You know, it’s very flexible. And, in fact, that’s, that’s the name of their rover. It’s called FLEX. And that’s an acronym, which I’m not going to try to remember right now, but it, it’s basically, it is standing. The astronauts are standing, or you might say, kind of leaning, but yeah, not in a full recline or seated positions. They’re, they’re going to be in the front of the vehicle. Just kind of gives them a good, you know, view of everything that’s in front of them and the wheels below them. So astronauts are there. They’re driving up for more of a standing config. They the thing can drive over a payload and kind of squat on it and pick it up and carry it, carry it away, kind of pallets or other other types of payloads, cartons, like all of them do, they have a very good robotic arm for doing science. So picking up rocks and, you know, drilling, that kind of thing. Different end effectors give you different scientific capabilities. So that’s the. FLEX rover from astrolab. Then we’ll move to the Denver area in Arvada, Colorado. We have lunar outpost, and what they call lunar dawn. This vehicle looks more, I guess, like a lunar truck, more of a pickup, if you will, in that the astronauts are seated, but more in the forward part. And there’s a, there’s a gate in front of them that drops down to become kind of a step, you know, a ramp to get on. And the payloads are in back, on the flat bed and back. And then there’s, there’s a EVA tool storage on the side. And again, they got a rover Iran, arm manipulator in the back there for all the scientific needs. So we’ve got the FLEX, which looks like a very large Mars rover. And then you got the lunar Dawn, which is more like a space truck, Moon truck. And then finally, you got our local guys into the machines here in Houston, they’re over by the NBL, just up Space Center, and they have what they call Moon Racer. And again, racer is another acronym which I’m not going to try to try to spell out, because of course it is. They’re all acronym. It’s acronyms all the way down. And I don’t know my first your first impression looking at that is like a Baja racer. So the racer name is applicable. There’s now, instead of the astronauts being standing or being more seated in front, now they’re more in the middle, maybe more like an LRB was seated in the middle of the vehicle with some storage up front, you know, some in back, the manipulators again and back. Let’s see they have a big solar panels. Well, they all have big solar panels, but the way that they deploy them is different in all three cases, which, again, is part of the innovation. So I guess those are the at least cosmetically without going into details, which will quickly get me in trouble. Those are the three visible differences, you know, supercharged Mars Rover with a with a nice crew cabin in the flex lunar Dawn, as the moon truck, where they’re seated in front, and then Moon racer as the Baja racer, maybe,

Nilufar Ramji

yes. And until NASA makes its selection, you can’t talk about who your favorite child is right now.

Steve Munday

I have no favorites. I love them all equally.

Danny Newswander

He has one favorite. It’s called the pressurized rover.

Nilufar Ramji

So before we go to the pressurizer, I know Danny, you’re dying to talk about it. I just have one last question for you, Steve on LTV, so where is the contract currently in its development, and when does NASA plan to make the selection? You talked a little bit high level at the top about this.

Steve Munday

Yeah let me give you the overview. Is the three phases, phase 123, we’re currently a nearing the end of the one year phase one part, which takes you from ATP concepts to PDR. I’m flying out tomorrow to start, you know, one of the, one of the contractors PDR, and we’ll be doing the PDRs for the next few weeks, and then we’ll close all those out next next month, maybe June. Anyway, by the end of June, we’ll have all three of those contract, those PDRs closed out on July 1, we plan to drop the rooftop RFTOP, request for Task Order Proposal, because they’re all, they all remain on contract. Now it’s just task orders within that contract. So the next demonstration mission, task order begins phase two, and that’s the task order to go. Okay, now we’ve seen your preliminary design. Now go develop, test, certify it, and get us to the moon for a demonstration mission. It ends with a demonstration on the moon, on the lunar South Pole. At that point, we begin phase three, which are standard missions. So now we buy a mission a year at a time, basing on an annual cadence. We say, Okay, we need one for Artemis V. Okay, now we need another one for Artemis VI to buy another one. I mean, another task order, not another vehicle. Hopefully it’ll be the same one doing, that’s the that’s the idea of LTV. It’s a very reusable vehicle long term. Okay, so, so we’ve got the three phases, right? The total period of performance, 15 years, because we’ve got one year of preliminary zone, maybe four years, or a little less, of development and demonstration on the moon and then 10 years of service.

Nilufar Ramji

Fantastic. And for our listeners who are following along today, the selection of the contractor, who does win the contractors only one vehicle that is selected, and that same vehicle will be the one that goes to the Moon

Steve Munday

Yeah, started to say on July one will put. The rooftop out there for them to come back with proposals for why they are the one that should be given the demonstration mission task order and go to the moon. We hope to make those selections and ATP start it by the end of the year, so over the summer, that’ll be our summer homework is evaluating proposals and selecting one to hopefully begin that demonstration mission task order by the end of the year.

Nilufar Ramji

More to come.

Steve Munday

More to come. Very exciting. I think Danny is partially correct that my favorite rover is PR, because

Danny Newswander

90%

Nilufar Ramji

I’m sensing a bit of a sibling rivalry happening here.

Danny Newswander

We’ve worked with each other for what, 10 years or something, on and off. 10, 15 years, lot of respect, lot of mutual respect. But we try to have fun with it too, just because it’s what makes the job fun. It’s fun, it’s challenging.

Steve Munday

He used to be my boss.

Nilufar Ramji

It’s on the record. Well, Danny, let’s talk a little bit about your relationship with JAXA, or the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, as well as the pressurized rover. There is a NASA Japan implementation arrangement, from what I understand, and NASA is procuring the pressurized rover a little differently than how we’re doing the LTV. We’ve talked a little bit about that at a high level, but can you tell us how NASA and Japan are working together on the PR and what that international collaboration looks like?

Danny Newswander

So as as I mentioned previously, as part of you know, there’s been a lot with the Artemis accords. There was a framework that was put together between the United States of America and the country of Japan. And coming out of that was this implementing arrangement, if you will, where Japan came forward and said, Hey, is our contribution to Artemis. We would like to provide this Pressurized Rover. This is what we are going to do. And in suit, NASA said, Okay, we’ll launch it. We’ll get it on the moon. And there’s some things back and forth as far as how you go through the development of it. So it’s not really a contract. It’s more of a an arrangement where we both agree to come forward and as partners make the pressurized rover a success. And so to do that, since you don’t have a contract, I can’t provide them like, if there’s something additionally that we would like to pressurized rover to do, I can’t go make a contract mod. I can’t put more money into something. I can’t go give them money and say, go put this on your vehicle. They have to internalize that and go find a way to bring it forward if you know they’re in agreement with what we want to do. So it really, really makes the relationship based off of mutual trust, mutual partnership trying to get there together. We put a lot of emphasis on trying to have the conversations at the lowest technical level possible, so our individual that’s over structures is talking directly to their individual that’s over structures, the person that’s designing the windows on their side, or the teams that are designing the windows on their side, are working hand in hand with our engineers that have that knowledge about how do you put a window on the lunar surface. And so because of that, we’ve really focused a lot about doing things together as much as we can. We fly a lot to Japan. They were just here the last two weeks, having lots of conversations with a lot of our technical team members. And I was in Japan the week before, talking to them about lots of things with another team that was touring some of their facilities and talking to their engineers. So there’s a lot of focus on this partnership, this culture about working together at the lowest technical levels as possible, because our job is to make sure the vehicle is safe. It can enhance science, both and utilization, both in crewed and uncrewed situations, but also that it meets what Artemis needs it to meet. Their job is to try to take all that and actually like do it, which is very, very challenging. And so our focus, because there’s no contracts, there’s no way to send funding over to enhance their design, we really focus on this partnership and this communication and building kind of a mutual team and this trust so that when we bring something forward, we can have the right conversations about why that’s valuable and why it should be on the pressurized rover. At the same time, we can listen intently to the challenges of doing so and what trades happen if you put that on the rover, what might have to come off because of that. And so it’s this frequent communication, as much as possible, face to face. But we also utilize every type of communication Avenue or our medium that you can think of to try to get there. I don’t know if

Nilufar Ramji

That really does help, all the words that are coming into my brain, our collaboration, our mutual understanding and respect. It’s to look at all of the redundancies as a team, not as one entity or another, as NASA or JAXA, but together. And what keeps coming to my mind is we have this video that we did when we when the agency named the Artemis campaign called we go together, right? This is the epitome of that in my brain,

Danny Newswander

right? And it’s not trivial, because in Japan, in the US case, it’s not just that we’re on other sides. You know, I laughed when he said, I’m going to start from the west and move you’re not you’re not far enough West. Go a little further to the east. You go farther west. But I laugh because time, just time zones is huge with us. I mean, their morning begins when we’re going to bed, type of a thing. So how do you have the right dialog? And then it’s not trivial to get teams over to Japan. International travel has a lot of nuance to it that is really challenging. Then when you go over there and where they come here, I mean, you’re having meetings when you should be asleep, and they’re having meetings when they should be asleep. And you you get into, you know, that focus and concentrations that needed, and you stack on top of that. There’s a different culture. They approach problems completely different than we do. There’s language challenges. You think you’re talking the right stuff, or you’re talking to each other, but you’re really talking past each other, because they’re assuming what you’re saying, and you’re assuming what you’re telling, and they don’t really line up. So there’s communication is really key. But, yeah, you’ve nailed it exactly. It’s this collaboration, but it’s very, very nuanced, and it’s something that you know you have to really, really watch closely and really try to improve as you move forward.

Nilufar Ramji

I love it, and I have a couple more questions. We talked a lot about the LTV capabilities and the science and the differences of the vehicles. In a nutshell, could you describe how the pressurized rover will enable Artemis astronauts to conduct more science on the moon or traverse more of the lunar surface?

Danny Newswander

Yeah. So I always tease Steve about this, because when we’re in meetings and stuff, and we’re talking about, say, food, which is a necessity and is a challenge for the lunar surface, I always look over and say, Hey, what’s your thoughts on food? What are you guys doing about food? And of course, there isn’t any. So, yeah, we have some fun with it. You know, I think it really allows your home base to be a little farther away from your landing site, so that you can utilize the space suits and the great capability they bring, plus the LTV and go to some different places that the utilization Science Technology type communities want to go to. I think that’s kind of your big thing. From a crewed perspective. It really, really allows you to do some of those things from an uncrewed perspective, where it really helps with enhancement of Sciences. You know when? And a lot of this is when we always talk about JAXA, when we talk about the pressurized rover, is really Japan. This is their real first opportunity to explore the lunar surface from a country perspective. And so got it, you’ve got a lot, there’s a lot of participation in Japan. This is really a Japan’s rover. It’s not really a JAXA rover. It’s really Japan’s rover. And so when you get into like science, their science community is really, excited about the ability to have something that Japan is bringing to the table, to go off and do this uncrewed sciences. It’s one thing they have a very good international collaboration from a science perspective, but it just means a lot to their country for them to be participating in achieving that science versus just working with someone else who’s doing it for them. It’s definitely a point of national pride, yeah. And so from that perspective, this vehicle, the crewed piece, is phenomenal. What it brings that ability to drive shirt sleeved on the lunar surface to location and then be able to do space walks or get on your LTVs and tool around, right? Is amazing. But the uncrewed is one of the more challenging pieces, because it is lunar surface is challenging, and you’ve got this ability that you need to be able to drive it from home, or it needs to be autonomous. But the science potential that it’s starting to bring in that community as they start to get creative of how you do that, and the fact that Japan is contributing to that, I think also is really an important thing to consider.

Steve Munday

Jack says prime contractor is not a secret, right?

Danny Newswander

Well, so right now, I knew he was gonna ask that, Danny threw the food thing at me. So,

So one of the things that’s been challenging about this, right? Is just like Steve is not letting out his official contract until he gets to a certain point, right? JAXA is still, you know, they’re what we call Sr, SER, your system requirements review and your system design review is when, typically they say, Okay, this has been successful. We know what vehicle we’re building. Now let’s go find a contractor to do that. They’ve been to try to accelerate things, buy down risk, so it’s not as risky of a proposition. Once you get to that point. They’ve been very, working very, very closely with Toyota Motor Company as their prime, if you will, through through smaller contracts, not you know, the major contract. And so right now, Toyota is acting as the prime, and more unlikely. Once they get to that point, Toyota will continue to act as the prime. See is that what you’re pulling on exactly

Steve Munday

Exactly because this is another reason that PR is my favorite rover, because you drive Alex, because I have a Land Cruiser. This is the lunar cruiser.

Danny Newswander

Yeah, that is the term. You’ll hear a lot, lunar cruiser. Okay, it’s not official. It’s something that Toyota uses. If you go right now, they’re having the World’s Fair, I believe world’s Expo in Osaka, Japan. Believe it started in April. Goes through October. They’ve unveiled the latest design of the pressurized rover, the as they call it, the lunar cruiser. It’s not a term we use a lot yet, because until Toyota is officially on contract, I think it’s just something that Toyota is using for branding or whatever purpose, or to make Steve love the pressurized rover more than other rovers. Is that was my first call to Japan. Hey, could you call it something cool? So Steve will actually like it

Steve Munday

success.

Nilufar Ramji

Well, I’m gonna keep going down the pressurized route just a little bit longer. I have two more questions for you. Danny, so what kinds of testing has the pressurized rover gone through so far?

Danny Newswander

A lot more than you think. Okay, we’re still early. We’re still in the requirements phase, so technically, we haven’t decided yet what is being built, right? But there’s been a lot of testing, both on the US side and the Japan side, and even some testing we’ve done together, a lot of it’s just to understand the challenge, right? You have an idea of what you think the technologies, capabilities need to be but but actually, like doing some testing to understand that better is extremely valuable. There’s something we a term we use. It’s called HITL. I don’t know if you’ve heard it, human in the loop testing. You’ve probably heard about it, yeah. So we’ve done a lot of that here. We built some mock ups. Here in Houston, we’ve had astronauts participate, engineers participate, the Japanese participate, where we’ve tried to better understand how you bring cargo in and out of the pressurized rover, how you stack the pressurized rover. I mean, one of our biggest assets is you’ve got this pressurized volume, if you will. One of our biggest challenges is you have a lot of stuff to put in the pressurized volume, and you have to be able to work in that volume when you’re driving around without just reorienting it all the time. And so we’ve done a lot of those type of tests to better understand that, better understand ways we can inform the Artemis community or the architecture community about ways to improve those, the cargo configuration, or different things, so that we can try to solve problems now so they don’t become problems later. One of the techniques that Japan is doing is because of the challenges, they’ve done a lot of developmental testing earlier than you would in your classical development cycle, they’ve really looked closely at parts, components, even systems where they have a lot of what we would call engineering models. They call them breadboard models in different places. In Japan, they have the rover, the chassis, part, the tires, the wheels, that they’ve used to try to understand how it navigates through lunar type surfaces, how the systems play together, the components, the parts, to try to understand and identify areas that they need to be worried about, things that they can do, or even, are they understanding the problem correctly? And so there’s been a lot of what you could call developmental testing once we get on the other side of the requirements phase, they’re planning to build a flight like, type mock up, drivable mock up, and you know, it won’t have the pressurized section on it, but just from a mobility perspective, to really understand. And so a lot of testing has been done. There’s a lot more to go, but everyone’s trying to lean forward and to understand the problem and find ways to come up with solutions earlier than later,

Nilufar Ramji

High level, timeline, tentative timelines. What? What does it look like? What are the next set of milestones for the pressurized rover?

Danny Newswander

The biggest one here, which we’ve been working towards for years, is this summer. We have what we call a joint. It’s partnered sor SDR, where we’re really trying to say, this is the pressurized rover we’re building, and a couple months later they’ll have theirs in Japan, where they’ll say, this is the pressurized rover we’re building, and this is what we want the contractor to go do their contractor, right? So that’s the big one for me, is we’ve got to understand what this pressurized rover is, so we can start moving towards that, that next phase, which is really getting to the design and development of it. I’m also excited this summer, in a couple months, we have several crew US, crew members, and I believe one or two Japanese crew members meeting in Japan to kind of do some of this HITL testing with some of the mobility aspects, the windows, how you know, the driving of the vehicle, if you will. And so I’m really excited about that, because we’ve had a lot of engineers looking at it from both sides, and having some crew members who actually do this for a living, who bring unique perspectives to be excited. Japan’s a hard place to go to. It’s far. It takes a while to get there. It’s like 24 hours door to door, type of an experience every time you go, not like Denver an hour, maybe if

Nilufar Ramji

sibling rivalry continues.

Danny Newswander

So I’m excited about that, because not only is this collaboration and the engineering or the project level, we really need it to be across, you know, NASA, and having the astronauts get together and not only build that collaboration among themselves, but also build it with us, is going to be extremely valuable for the success

Nilufar Ramji

Agreed the HITL testing is so important because these are the people that are going to be driving this thing on the moon. So the best people to give you that feedback are the crew fun question for you. Tell me how to say pressurized rover and Japanese, because you can thank Steve for that.

Danny Newswander

so this is a tricky thing, because a lot of terms are used, right? Lunar cruiser is the one that they use a lot of, especially Toyota, when I speak with them, a lot of times, they just call it the “rover”, which is just rover. Is the Japanese way to say rover, right? They are. They really do like English. They think it’s interesting. They like to try to mimic those words. Plus, I think there’s a little bit of just trying to communicate with us. They use the term pressurized “rover” a lot too. But if you really want to know what it’s called in Japanese, what it’s written in Japanese. It’s called the kaatsu getsu menscha, which gets you mensha, yeah, which just means pressure, Moon surface. Car is the way they kind of, they just bring the characters together to form the words. So thank you. Say that again, Steve. You want to try to say that?

Steve Munday

I do not

Nilufar Ramji

okay, kaatsu gets you mencha.

Danny Newswander

Oh wow, she is gonna work this out of a job.

Steve Munday

I’ll leave it to the experts,

Danny Newswander

but I will tell most of the time it’s, you know, when they talk, when Toyota talks, it’s Lunar cruiser. When I talk with Jax or Toyota, it’s usually “Pressurized Rover”, but most of the time it’s in English. So. It’s pressurized rover.

Nilufar Ramji

Very cool. Steve, you talked a little bit about what you’re excited for in the upcoming months. Is there anything else that you’d want to add or share about the next few months in the selection process for LTV?

Steve Munday

Sure, So just looking back over the last year, the only thing, the only test we required on the NASA side was one static mock up HITL test, so human in the loop, testing, where we had crew members in pressurized suits on their static mock ups that all three contractors delivered last, say, September, and then over the fall, we did the testing, which went very well, which informed them a lot of things that fed directly into design changes that they have all three made leading up to PDR, so very successful series of tests, as far as helping them see, okay, you know, you’ve designed, you design what you think astronauts want to, you know, want when they try to get in and out of and use and, you know, manipulate things. Here’s what we’re really seeing with real astronauts in real suits. The impressive thing, and I guess again, attributing this to the competition that we’re seeing between the three contractors, all three have in that year also developed drivable units. So they love drivable prototypes, which we did not cool, which we did not require. They did all this on their own, and we’ve been able to see their internal testing. They’ve done a lot more internal testing than we required on our, yeah, we just had the one HITL test. And in addition to that, they’ve had lots of internal testing on, you know, their own facilities, hiring their own astronauts. I’ll say that. How? I mean, Moonwalker on your resume is, you know, pretty lucrative these days. You know, you’ll get hired. You’ll get hired to come check out there, especially if you’ve Moonwalker who, who with experience in LRVs. You know, that’s a good thing to have. You can get hired by these companies. I know that’s a pretty Select Field, hard to add to your resume now, right currently. So looking through the to the next phase, eager to see what extras we see there too, because we saw a lot more. Got a lot more than we had required for this one year. First phase, you know, in four to 11 months, all three developed, not only static, but drivable, somewhat autonomy, some level of autonomy or teleoperation, yeah, seeing what the and imagine that’s in 4 to 11 months again, looking at the power of commercial competition. If NASA had done this internally, it wouldn’t have been done in four to 11 months. Any of this. So looking forward to the next phase, we require a drive, a similar HITL test, but with drivable units in a a lunar landscape simulator. Over here we call the rock yard, where, you know, there’s big rocks and craters and hills mimicking features on the moon. And so we’ll require all three to bring their engineering development units, edus in their drivable prototypes, basically. And where are again, our suited astronauts can try them out driving around. Now, you know, go beyond the static testing. So that’ll be early in the in the next phase. But again, I can’t wait to see what all the other testing that the contractor will do on their own, because their motivation is not only to police NASA, but to police their commercial partners. Again, they’re commercial customers, so it’s in their interest to go as fast and as quickly as possible.

Nilufar Ramji

There’s two things I’m taking away from your response. One is your level of excitement. It’s contagious. And number two is the spurring of the commercial lunar economy here on Earth. So it’s not only happening on the moon. You’re seeing it before we even get to the moon,

Steve Munday

all three have customers lined up, and I’ll go back. It’s interesting to see the interplay between the three, or at least for astrolab, they got a lot of JPL heritage, and you know, some some SpaceX ties, the lunar lunar dawn or the lunar outpost folks. And intuitive machines are competitors in LTVS, but they’re partners for clips, because the intuitive machines never see Landers. One of their payloads was and will be smaller robotic rovers from lunar outpost. So, yeah, it’s very cool to see, and that’s all you know. Credit clips for that, for driving that part of lunar economy. Saying, Okay, if we get these lunar you know that they’re basically not only driving lunar landers, they’re driving rovers directly by, you know, giving a payload slot, making that possible for one of our providers to put a little rover on there.

Nilufar Ramji

Anything that you want to share about pressurized rover before we sign off today,

Danny Newswander

we’re just excited. It’s a challenge. It’s a challenge. Technically, there’s a challenge. Just as Artemis is coming together, all how the all the different pieces play together. It’s an honor to be a part of this effort, to work with the country of Japan, and to work with NASA and all the individuals that work within NASA. And it’s something that, you know, I try to think of it is a marathon, kind of a sprinted marathon, maybe is a better way to say it, but it’s just something that is going to take a while, and we’re going to keep working together, and we’re going to get there, but there’s going to be a lot of challenges along the way, and I’m excited to be part of it, and excited to be part of you know, its success in the future.

Nilufar Ramji

I’m excited to be following along on both of these journeys. But Steve, Danny, thank you so much for joining us on Houston We Have a Podcast today.

Both Guests

You’re welcome. All right.

Nilufar Ramji

Thanks for joining us. You can check out the latest from around the agency at nasa.gov and learn more about the lunar terrain vehicle and pressurized rover at nasa.gov/suits-and-rovers our full collection of episodes and all of the other wonderful NASA podcasts can be found at nasa.gov/podcasts on social media. We are on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, X, and Instagram. And if you have any questions for us or suggestions for future episodes, email us at nasa-houstonpodcast@mail.nasa.gov. This interview was recorded on April 28, 2025.

Our producer is Dane Turner. Audio engineers are Will Flato and Daniel Tohill. And our social media is managed by Dominique Crespo. Houston We Have a Podcast was created and is supervised by Gary Jordan. Special thanks to Victoria Ugalde And Tim Hall for helping us plan and set up these interviews, and of course, thanks again to Steve and Danny for taking the time to come on the show.

Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on, and tell us what you think of our podcast.

We’ll be back next week.