Editor’s note: An update to this story, Artemis II: The Ground Teams Powering NASA’s Moon Mission, was published on March 4, 2026.

This episode has been updated to reflect changes to the Artemis program. For more details about those changes, refer to NASA Strengthens Artemis: Adds Mission, Refines Overall Architecture.

Episode description:

Behind NASA’s Artemis II mission and the astronauts who will fly around the Moon, teams on the ground are essential. Explore some of the epic equipment that makes Artemis II possible—the mobile launcher, crawler-transporter, and NASA’s barge Pegasus—and meet a few of the many specialists who act as the shoulders lifting astronauts into space.

For Artemis II news and the latest launch information, visit nasa.gov/artemis-ii

[MUSIC: “Supercluster” by Sergey Azbel]

PADI BOYD: You’re listening to NASA’s Curious Universe. I’m Padi Boyd.

JACOB PINTER: And I’m Jacob Pinter. NASA is leading a golden age of space exploration. The Artemis II mission will send humans around the Moon for the first time in more than 50 years. It sets the stage for future Artemis missions when astronauts return to the Moon’s surface. And Artemis will build upon the foundation we’ve laid and prepare us for the first human journey to Mars.

PADI: In this limited series, you’re along for the ride of Artemis II. You’ll meet the astronauts flying around the Moon and go behind the scenes with NASA engineers and scientists powering this mission.

JACOB: This is episode five of our Artemis II series. In this episode: the ground support that sends humans to deep space. Artemis missions rely on many people working together, and they depend on specialized equipment that’s just really cool.

PADI: We’re going behind the scenes with a skyscraper that can move, giant machines that carry rockets to the launch pad, and the people at the controls making sure they do their job perfectly so astronauts can have a safe trip around the Moon.

JACOB: Before we get too far, I just want to make sure you know how important this stuff is. And don’t take it from me. Take it from Victor Glover, one of the astronauts about to fly around the Moon. He’s the pilot for Artemis II. When I interviewed Victor, he shouted out the program that is formally called Exploration Ground Systems. There’s the launch pad, the infrastructure that delivers fuel to the rocket, and the procedures that recover the astronauts when they come home or get them to safety if there’s an emergency.

VICTOR GLOVER: It’s a big deal, but it often gets kind of overlooked because of the rocket and the spacecraft. The rocket and the spacecraft get all the attention. The pins and the posters, they always put that in, and nobody wants to just see like a flat piece of concrete, you know? But that represents Exploration Ground Systems, and I think we should make pins. We should make more t-shirts.

JACOB: Flat concrete pins.

VICTOR: Flat concrete pins, man. That launch pad and that group that’s going to meet us out on the Pacific Ocean and pick us up out of the water and get us back home safe—that’s a big dang deal.

[MUSIC: “Running Late” by Claire Leona Batchelor]

JACOB: So let’s talk about a big dang deal. Just like the Apollo launches to the Moon, more than a hundred space shuttle launches, and now some commercial launches by private companies, Artemis II will lift off from NASA’s spaceport: Kennedy Space Center in Florida. I got an up-close look at the launch facilities with an engineer named Jesse Berdis.

JESSE BERDIS: Welcome to Launch Complex 39B. So we are standing in the middle of a field inside Launch Complex 39B, and about a half mile from us is the actual launch pad. And then beyond that about another mile is the Atlantic coast, the beach.

PADI: The rocket getting Artemis II off the ground, which is called SLS, is the most powerful rocket NASA has ever built. To launch a big rocket, you need some big equipment.

JACOB: What first catches your eye at the launch complex is all the stuff that’s mechanical or concrete. The pad itself is a concrete pedestal sloping up gently from the flat Florida coast. There are tanks for rocket fuel and three tall metal towers. Those are lightning rods so the rocket doesn’t get struck.

But I was surprised to find that Jesse and I were actually standing in a green, grassy field. Kennedy Space Center overlaps with a national wildlife refuge. There are more than 300 different species of birds here. And since this is Florida, you never know where you might see an alligator.

JESSE: And you know, you have to be careful because there’s snakes and stuff. You’re in wildlife territory here.

JACOB: Jesse is the deputy project manager for modifications to the Artemis II mobile launcher. When you see the rocket on TV, ready to blast off, you’ll notice that it’s attached to a big metal tower. This is the mobile launcher. When I visited, there was no rocket on the launch pad—not yet. The mobile launcher stood alone, towering above us more than 30 stories tall.

Jesse still remembers the first time he saw something like this. He was in college in Oklahoma, about to graduate with an engineering degree, and he tagged along on a school trip to Florida. Seeing NASA’s launch facilities left him in complete awe.

JESSE: The first thing you do when you come out here in flat Florida is you look up, because the equipment out here and the superstructures out here are amazing. They’re just essentially skyscrapers in their own.

PADI: NASA has been using mobile launchers since the Apollo missions in the 1960s and ‘70s–although the mobile launcher for Artemis missions has new upgrades. The mobile launcher is the rocket’s lifeline. It’s a platform, it’s a source of fuel and electricity, and it even has the elevator that takes astronauts up to the walkway where they board their spacecraft.

JESSE: The backbone of that rocket while it’s on Earth is the mobile launcher, which is what we see in front of us. It stands about 380 feet tall. It weighs about 11.5 million pounds and it is movable. It is basically a skyscraper that can move.

PADI: If you’re wondering how it’s possible to move it, hold that thought. We’ll come back to that in a few minutes.

[MUSIC: “Wonder” by Claire Leone Batchelor]

JACOB: From a distance or on TV, you can’t see all of the intricate details that make the mobile launcher so valuable. It’s much more than metal. The mobile launcher holds more than 400,000 feet of cables and miles of tubes and pipes. A series of attachments called umbilicals provides power to the rocket, as well as communications, coolant, and fuel. And then, at the exact moment of liftoff, the umbilicals swing away so the rocket can fly.

JESSE: All of these systems are very simple systems, but they all have to work together at just the right time to make the launch happen. And that’s what the mobile launcher provides.

PADI: Something else the mobile launcher provides is a path to safety. Engineers and astronauts are doing everything they can to make the mission succeed, but safety comes first. It’s possible that once the astronauts are getting into their spacecraft on top of a rocket 300 feet above the ground, they need to get down in a hurry. And the mobile launcher can do that too.

JESSE: NASA always likes to have a backup plan. And one of the systems that we have invented and designed here is the emergency egress system, or we call it the EES. So on launch day, if there is any kind of event, any kind of emergency, we want to make sure that our astronauts are safe.

JACOB: This emergency egress system looks something like a ski lift or a gondola. At the top of the mobile launcher, there are four baskets, each about the size of a small SUV. If astronauts or any other crew members need to get down quick, they can hop in a basket, slide down what is basically a controlled zipline, and reach safety almost a quarter of a mile away from the rocket. When Jesse and I talked, we were actually standing right next to the landing area for these baskets. The landing zone is marked on the ground in royal blue. It’s a bright dash of color against all the metal and concrete at the launchpad.

JESSE: You’d be hitting about 40 to 55 miles per hour coming down. They would land here at the landing site and there would be three armored transport vehicles waiting for them. And they would evacuate into the vehicles and then egress off the pad perimeter site to a safe haven where you’d have, you know, essentially rescue crews waiting there for them or maybe helicopter support if needed.

JACOB: NASA has had earlier versions of this evacuation system going back decades.

PADI: Astronauts have never had to use them. But it’s one of those things you’d rather have and not need than need and not have.

JACOB: When I met Jesse in the summer of 2024, he had been focused on this for months. He was getting ready for a final test when the system could get an official stamp of approval. There were long, grueling days, but there were bright spots too.

[MUSIC: “Buttercups Bloom” by Laurent Dury]

JESSE: This is magnetic braking technology. This is the same style, concept of technology, that you would see at theme parks, like, you know, Walt Disney World or Universal or Six Flags, et cetera.

PADI: The emergency egress baskets use the same kind of brakes as roller coasters. Although NASA’s ride is nice and smooth. No loop-de-loops. Also, the Kennedy Space Center is just down the road from Orlando, Florida, and some of the most famous roller coasters in the world. So Jesse took a business trip along with some other NASA engineers.

JESSE: They allowed us after hours after all the park guests had left to kind of come see their systems with the lights on. And they were showing us their maintenance routines, their stockpiles of spare parts, what things typically break more often than others. We got a chance to meet with their maintenance crews and their mechanics. And it was a wonderful experience.

JACOB: As we kept talking, we noticed a team of technicians nearby. They were flying a drone and paying close attention to their computers. They were about to test the emergency egress system—a dry run, with nobody actually in those baskets—although we weren’t sure when that would happen.

I asked a question about an older emergency system, from the space shuttle era. Jesse started to answer, and then …

JESSE: It’s a similar concept. Yes. So in the—oh, here we go. Here’s the basket coming down. So right now it’s at a home-home position with the braking, and then it’s going to probably go into active mode, and you’ll see it start to slow down. I’ll stop talking so you can kind of hear it coming down the line.

[Sound of basket sliding, mechanical sound of brakes activating, then clicking to a stop]

JESSE: We call that a perfect landing. (laughter)

[MUSIC: “Fracture” by Jay Price]

JACOB: A few weeks later, the emergency egress system had its final test, and it passed.

PADI: This is just one example of NASA’s backup plans. There are many more. And other teams rehearse what they can do if something goes wrong. This process of testing and simulating makes sure that NASA is ready and that astronauts and other crew members can act quickly.

JESSE: So it’s kind of like—it’s like football practice. We want to make sure that if something were to happen, there are no surprises. The surprise is not how to operate the system, the surprise is whatever is out there that we need to be reacting to.

JACOB: When Artemis II launches, it will be the result of years of preparation. When we turn on our TVs and see the astronauts waving and smiling, we don’t see the engineers who spent 14-hour days working on the mobile launcher or the nights and weekends making sure something functions just right. Jesse says that the people working on the ground are smart, capable, and most of all dedicated to helping the astronauts succeed.

JESSE: So what I like to think is these men and women out here, they are the shoulders that are lifting the astronauts into space. The main part of the mission is up there. But it can’t happen without the many, many, many people in the Exploration Ground Systems program down here working that, and so I’m really thankful to be working with everyone on this team.

JACOB: OK, now it is time to slow down. In spaceflight, it seems like everything happens fast. Rockets fly at unimaginable speeds, fast enough to push astronauts back into their seats. Well, we’re about to move a lot slower. If the mobile launcher is essentially a 30-story tall skyscraper, what makes it mobile?

[MUSIC: “Provoke” by Jay Price]

PADI: When the rocket and mobile launcher are fully assembled for launch, the whole configuration weighs over 10 million pounds. That’s more than the Statue of Liberty many times over. Besides that, the launchpad is 4 miles away from the building that performs the rocket’s final assembly.

JACOB: And the machine that makes it all possible …

(to crawler-transporter team) Hi there. Is it alright if we come up?

Unidentified voice: Yep.

JACOB: … is the crawler-transporter. I am not exaggerating when I say there is nothing quite like the crawler-transporter anywhere else on the planet. Breanne Rohloff is one of the few people qualified to drive it.

(to Breanne Rohloff) I have some questions if that’s OK.

BREANNE ROHLOFF: Yeah, just watch your step. It’s very unforgiving grading. Don’t want to fall on it.

JACOB: Since the crawler-transporter is so unique, it’s also kind of hard to describe. The NASA manager who’s in charge of it told me it’s a cross between a locomotive, a ship, and a big piece of mining equipment. Also, it’s in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s heaviest self-powered vehicle. So let’s start at the top. Imagine a square-ish platform more than 130 feet long and more than 110 feet wide.

PADI: That’s almost 40 meters long and about 35 meters wide—or a little bigger than a baseball diamond. This platform is more than 20 feet off the ground. It can roll underneath the mobile launcher, pick it up, and carry it.

JACOB: And that’s possible because at each of its four corners, the crawler has treads like a bulldozer. And these are huge—something like twice my height. This whole thing is powered by diesel engines that get about seven feet per gallon.

Just to be clear: I saw the crawler-transporter before it rolled Artemis II to the launch pad. There was no rocket on top. Breanne leads me up into the cab, the place where you can actually drive this machine.

BREANNE: Yeah, so you walk in, and you have kind of a control panel. We’ve also got our steering mode, you know, forward, reverse, and neutral. (fades out)

JACOB: The inside of the cab is pretty plain. There are a few switches and gauges. Almost everything is dull gray, except for the steering wheel, which is bright red. And for such a big vehicle, the steering wheel is almost comically small. This cockpit is around 20 feet above the ground, so when Breanne is driving, it’s like she’s looking out a second-story window.

BREANNE: You’ve got your emergency stop button. You’ve also got your service brake.

JACOB: One thing you didn’t point out is this speedometer, I guess, and it goes from zero to two?

BREANNE: Yes. What most of us tend to look at actually in operation when we’re going down the crawlerway is this speedometer, because it spits out a digit—it’s a digital readout of how many miles per hour you’re going. And yeah, it’s zero to two. But we don’t go any faster than 0.83 [mph] with flight hardware. So you’re looking for pretty low miles per hour there.

PADI: Breanne is in her 20s. She started working here as a college intern. When she graduated, there just happened to be a job opening as a contractor, so she snapped it up. And to be clear, driving the crawler-transporter is only part of Breanne’s job. There is constant maintenance to do, and there is paperwork. But when it’s showtime—when those millions of pounds of rocket and mobile launcher are right above Breanne’s head—that’s the good part.

BREANNE: It’s not sitting behind a computer. It’s just—it’s fun. Like, it’s the bit that you look forward to you, you actually get out and you get to see visually, what everything’s kind of—what everyone’s been working for, especially when we have flight hardware, where you get to actually come out here, have it on top of us and then see it being transported from point A to point B and be a part of that.

[MUSIC: “Different Narrative” by Jay Price]

PADI: From the building where the rocket is assembled to the launch pad is a little more than four miles or close to seven kilometers. A fast runner could cover that in 20 or 25 minutes. For the rollout of Artemis II, the journey took almost 12 hours.

JACOB: Breanne and I stepped out of the air-conditioned cockpit …

BREANNE: Out into the heat.

JACOB: … and walked around the outside. NASA has had these crawler-transporters since the 1960s. Back then, a company that made mining equipment built them custom for the Apollo program. Those same two crawlers are still in service, 60 years later.

PADI: They’ve been repaired and refurbished constantly. And to get ready for Artemis—which uses an even heavier rocket than the Apollo program—one of the crawlers was upgraded so that it could carry 50 percent more weight than its original design. Everything about these machines requires special care, even the surfaces they drive on. The crawlers would absolutely destroy regular asphalt. Instead, all 4.2 miles of their path is covered in special gravel made of river rock, which is naturally smooth. Over time, the crawler grinds the rocks into sand.

BREANNE: So if you’re walking by the trucks, you can kind of hear that crunching and breaking down. You can also hear people walking on it and kind of kicking around gravel. But it kind of—it just has like a steady hum, once it gets going.

JACOB: When the crawler is in motion, there is a kind of ballet swirling around it. For one, the driver at the wheel has a backup driver standing right next to them, just in case. Also, there is a team of spotters walking around and technicians making sure the engines and hydraulics are healthy. For Artemis I, Breanne was right there in the middle of it all.

BREANNE: We take turns because it’s a long drive. And you want to make sure you have a fresh set of eyes. So we split off every, kind of 45 minutes to an hour, is what it typically ends up being. And I distinctly remember this because the last time we dropped the rocket off for Artemis I launch, I was actually able to drive it up onto the pad. I got very lucky with that assignment. That was a lot of fun.

JACOB: When you hit the pad and you got there, what were you thinking?

BREANNE: Am I in line? (laughs) Like, OK, what inputs do I need to line up? Because there’s not a lot of wiggle room up there. And then we dropped it off. And it was like, it’s here. We did it.

[MUSIC: “Natural Motion” by Paul Richard O’Brien]

PADI: And now, Breanne is doing it all over again—this time with a rocket ready for astronauts. She’s excited to see it all come together: the systems that were tested in Artemis I plus the new ones for Artemis II that focus on safety. The road to the launch pad is a long one. And it takes engineers like Breanne to push the mission forward, even when the load gets heavy.

BREANNE: We don’t get anything done out here without teamwork. There’s a lot that gets put into this before we even get to flight hardware and get to actually moving that I feel like doesn’t always get seen or noticed but is the backbone of getting all of this together and do a lot of, a lot of hard work.

JACOB: Breanne, thank you so much. Thanks for showing me around your office.

BREANNE: Yeah. Thanks for coming out here in the sticky summer.

JACOB: OK, one more thing to tell you about. This is another form of transportation that is not famous and not glamorous, but it is essential for Artemis II.

PADI: NASA’s rocket factory is in New Orleans. It’s called the Michoud Assembly Facility. Michoud is the place where NASA and its contractors manufacture parts for the rockets launching us to the Moon.

JACOB: Now, if you look at a map, you’ll see that New Orleans is hundreds of miles from the launchpad in Florida.

PADI: So how do you move big, heavy rocket parts that far?

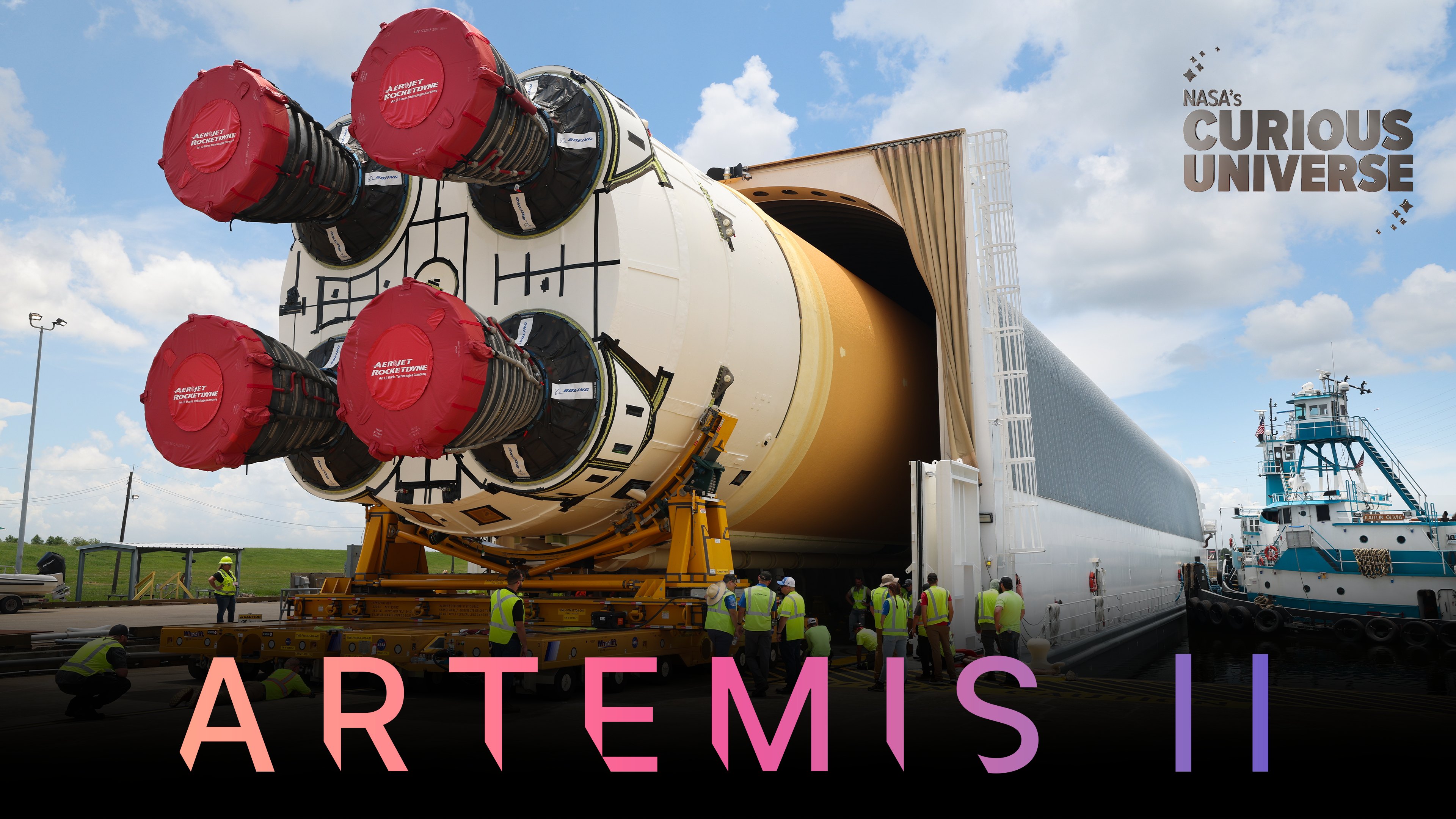

JACOB: I’ll give you a hint: not by land. NASA makes the trip across the Gulf of America with a special barge called Pegasus.

ARLAN COCHRAN: So I work at NASA’s transportation and operations group here at Marshall Space Flight Center. And so I’m responsible for Pegasus barge.

JACOB: Whenever you meet somebody at a party and people are asking, “Yeah, but what do you really do?” How do you explain your job?

ARLAN: You know, it’s definitely hard to just tell the public what you do, because they don’t truly understand the magnitude, the size of the Artemis program. So I actually—for the most time, I do not talk a lot at parties about what I do. I just tell them I’m in transportation and barge, and if you see something blasting off, it’s a chance that I had some role of getting it down to the Cape.

JACOB: This is Arlan Cochran—someone who, in my opinion, should talk about his job at parties. Arlan is endlessly curious about logistics. He’s always looking for ways to make things a little more efficient, a little smoother. Arlan sees logistics everywhere, and as humans venture further into space, he says we’re just going to find more and more logistics problems.

[MUSIC: “Keep Hope Alive” by Adam Richard Joseph Lyons, Paul James Visser, David James Ferguson, and Joseph Barboza III]

ARLAN: You and I go to the store every day, requires us to have some mode of transportation—logistics. And then we buy something that we go back and put it on a shelf—logistics. And we store it until it’s time to use it, when you’re ready to cook and you go grab it, or whatever you need to do—clean with it. And it’s logistics. There’s not going to be a store next to the Moon for you to go get that stuff.

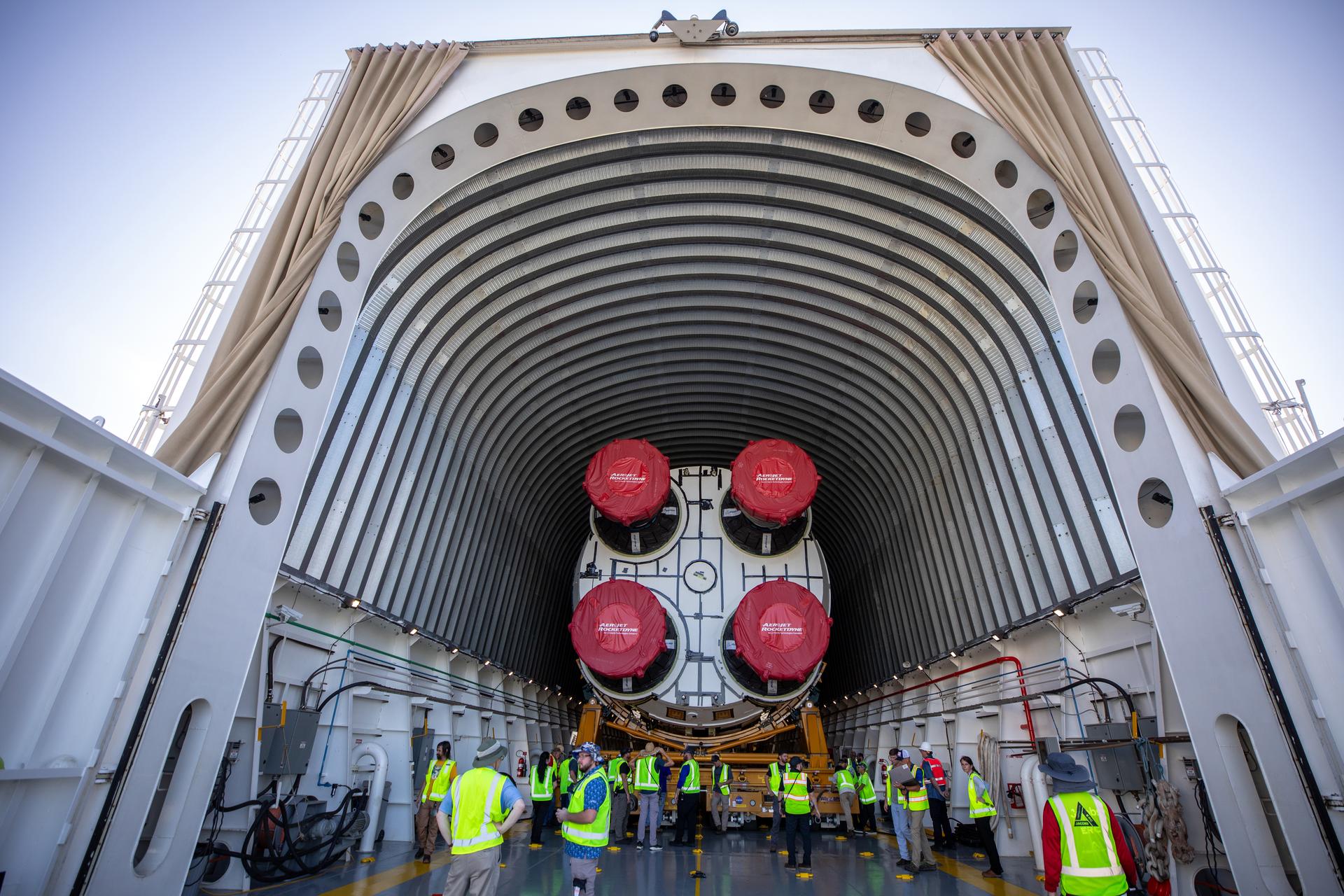

PADI: For now, Arlan handles logistics here on Earth. NASA has used barges for decades. Pegasus has been active since the 1990s, originally to move those big, orange tanks that fueled the space shuttle. To be ready for Artemis, Pegasus received a big upgrade. Engineers added 50 feet of length, making the barge longer than a football field. They also reinforced Pegasus with steel, so it can carry equipment weighing hundreds of thousands of pounds more than in the space shuttle days.

JACOB: When I spoke to Arlan, he had his game face on. Pegasus was days away from transporting a part of the Artemis II rocket called the core stage. The core stage alone is more than 20 stories tall. It has massive fuel tanks that feed the engines that will lift astronauts into Earth orbit. After months of build-up, the trip from New Orleans to Kennedy Space Center would cover 900 miles in about six days.

ARLAN: When you have such a long time to prepare you can over-guess things. You can second-guess things. You can do a lot of things. And so when we ship, it is the Super Bowl, right? It’s just—but you don’t have any pregame for the most part. You don’t have any preseason. You don’t even have a regular season. It’s just—you line up and they flip the coin and say, “This is the Super Bowl, go play.”

JOE ROBINSON: Isn’t it a great day to be a mariner on NASA’s barge Pegasus? Isn’t it a great day to be a mariner on NASA’s barge Pegasus?! Who does this for a living?! Who does this? This is great. How you doing, sir? Joseph Robinson, I’m the marine operations manager on board. (fade out)

JACOB: On the other end of the journey, once the core stage had safely made it to Kennedy Space Center, I had a chance to see Pegasus for myself.

[MUSIC: “Metaphysics” by Laurent Dury]

If transporting the core stage was the Super Bowl, I was in the locker room hanging out with the winning team. They were exuberant. They were exhausted. And they were very sweaty.

That voice you heard is Joe Robinson. He used to be in the Coast Guard. Now he manages day-to-day operations when Pegasus is on the move.

PADI: Because it’s a barge, Pegasus doesn’t sail under its own power. It needs a tugboat. That allows it to have a smaller crew than a ship of a similar size. It took just six people to make the trip from New Orleans to the Florida coast.

JACOB: And I should add, this crew transported a huge, irreplaceable rocket during hurricane season. They kept an eye on the weather, and thankfully it was smooth. But you can imagine everything that could go wrong in the open water.

JOE: We do a lot of training. We go through our checklists for loading, offloading. We do Coast Guard required drills and then some. Then we go to colleges for firefighting, and, you know, we’re all licensed mariners. We’re all marine firefighters, we’re all—so I have a lot of confidence in the crew, and that eases my nerves a lot. A lot.

JACOB: Standing in the cargo area of Pegasus feels something like being in a gigantic lipstick tube. The cargo area is about as long as one-and-a-half Olympic swimming pools with a vaulted roof more than 40 feet high. The floor has neat rows of built-in rings to tie down cargo. As Pegasus sails across the gulf carrying the rocket core stage, every hour around the clock, its crew performs an inspection to make sure everything is secure.

JOE: On the rocket particularly they were monitoring pressures inside of the liquid hydrogen tank and the liquid oxygen tank, and we’re making sure that that stayed within parameters. There’s a lot to do in this space. I mean, all you got to do is everything and then you’re good. (laughs)

JACOB: The crew is not only responsible for the rocket. They have lots of chores to do, including taking turns cooking. People had a lot to say about the food. On this trip, the coffee machine broke. That was painful. Joe told me about a time he tried to make egg salad sandwiches for everyone. They turned out terrible, and the other guys still tease him about that.

In the pilot house—which is kind of like the command center for the barge and, most importantly, has air-conditioning—I met another crew member named Scott Ledet. He’s the engineer.

SCOTT LEDET: Well, I’m like Motel Six. I keep the lights on, make sure the generators are running, performing up to our standards. I do the maintenance on board, make sure all the winches are working, the caps and things are full of hydraulic. I make sure the electrical is performing like it’s supposed to.

JACOB: Like Joe, Scott had years of experience in the marine industry before he got this job. But he’s had his eye on NASA for a long time. During the Apollo program, Scott’s grandparents helped build the Saturn V rocket.

SCOTT: And my grandpa did the electrical on the Saturn and my grandmother was a storage keeper there. So it’s kind of cool that I just kind of fell into this position doing the same thing they were doing. You know, they made history with helping them land on the Moon, and we’re making another part of history.

JACOB: Scott helped me understand just one example of all the little things that have to go right for Artemis II to succeed.

[MUSIC: “Pulling the Line” by Jonathan Elias and Sarah Trevino]

To launch the rocket, you have to transport it to Kennedy Space Center. To transport it, you have to load it onto Pegasus. To load it onto Pegasus, you have to make sure the barge’s lip is exactly level with the platform on land. One of Scott’s jobs is making sure the ballast tanks inside the barge have the right amount of water to keep that lip level. If something goes wrong—like if there’s damage, or if Pegasus can’t do the job—there could be ripple effects across the entire mission.

PADI: Artemis II relies on many other people like Scott. People like the crawler drivers and engineers who work on the mobile launcher. They’re all specialists who do their jobs as well as they possibly can, and then they pass the mission on to the next person.

JACOB: As Scott and Joe told me about life at sea, I couldn’t help but think about what they have in common with astronauts. In space, astronauts are crazy busy. They have a relentless checklist. But then they get to look out the window and see something that most of us never will.

SCOTT: And you don’t get any better sunset than you do out in the middle of the ocean, calm seas. It’s just nice. Peaceful. No cell phones going off. No people bugging you.

JOE: Stars touch stars out there.

SCOTT: You just do your job and enjoy life.

JACOB: I know that you’ve got a ton to do while you’re in motion, but do you ever look up and think, Holy smokes, that thing’s going to the Moon?

SCOTT: Every time I wake up and get a cup of coffee and look out that door and take a sip. (laughs)

JACOB: It must be a cool feeling.

SCOTT: It is a very cool feeling. This is the most rewarding job that I’ve had. It’s probably the most important one that I’ve had. You know, we are very specialized in what we do and how we do it. And we like to do it down to the T and make it perfect. Nobody’s perfect. We’re all going to make mistakes. But we like to make it as perfect as possible, because we know that we are putting people on there. And we want them to come home to their families—just like when we leave and we travel across the gulf or go down the river, we want to go back and see our family. So we take that same pride in ensuring that our job is done correctly, the way it needs to be done. That way they can have a successful mission, and then go back and see their families.

[MUSIC: “New Discoveries” by Al Lethbridge]

JACOB: After some more talking, I said goodbye to the Pegasus crew. A few months later, they sailed through the gulf again. This time they carried hardware for Artemis III—

PADI: —the future mission that will return humans to the surface of the Moon and prepare us for the next giant leap.

JACOB: Mars. There is a lot to explore.

PADI: So it’s time to get to work.

[MUSIC: “Inner Peace” by JC Lemay]

This is NASA’s Curious Universe—an official NASA podcast. Our Artemis II series was written and produced by Christian Elliott and Jacob Pinter. Our executive producer is Katie Konans. Wes Buchanan designed the show art for this series. Music for the series comes from Universal Production Music.

JACOB: We had support throughout this series from Rachel Kraft, Lisa Allen, Lora Bleacher, Brandi Dean, Amber Jacobson, Courtney Beasley, and Thalia Patrinos. Huge thanks to the subject matter experts you heard in this episode, as well as Jose Perez Morales, John Giles, and John Campbell. At Kennedy Space Center, we had help from Toni Jaramillo, Tiffany Fairley, and Allison Tankersley. At Marshall Space Flight Center, we had help from Corinne Beckinger.

You can find transcripts for every episode of Curious Universe and explore NASA’s other podcasts at nasa.gov/podcasts.

If you enjoyed this episode of NASA’s Curious Universe, let us know. Leave us a review wherever you’re listening right now. Maybe send a link to one of your friends. And you can follow NASA’s Curious Universe in your favorite podcast app to get a notification each time we post a new episode.