Featured Articles

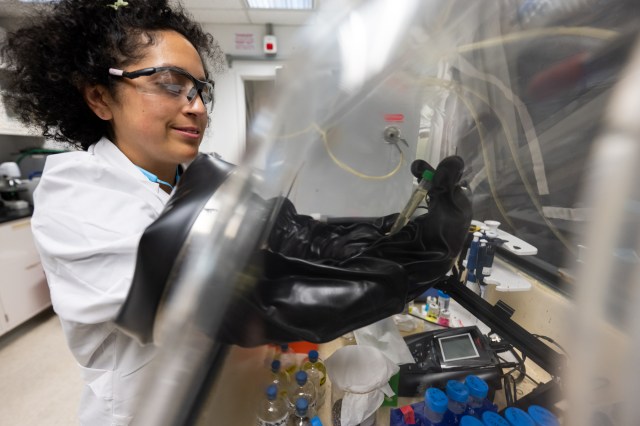

Top Federal Agencies For Diversity, including NASA Glenn

Top Federal Agencies for Diversity by Barbara Frankel.

Last year, we decided to survey all federal agencies to determine their commitment to diversity in the same four areas as The DiversityInc Top 50 Companies for Diversity®: CEO (agency head) Commitment, Human Capital, Corporate and Organizational Communications and Supplier Diversity. Based on our knowledge of any federal agencies, we suspected only a handful would emerge as real diversity leaders. DiversityInc was right about that. But what surprised- and disappointed-us was the lack of participation. DiversityInc sent our survey to more than 300 federal agencies. We called, checked back with them repeatedly to answer questions and encourage participation and even extended the deadline five times to allow more agencies to participate.

What was the result? Only six federal agencies participated, and all of them show some diversity strengths. What does that tell us about most federal agencies? They don’t “get” the importance of diversity to their central mission and they aren’t doing much of anything to improve. DiversityInc is hoping this will change for the better under the Obama administration, so we will be running this survey again, e-mailing out invitations to participate in July with an October deadline.

We would like to praise the six federal organizations that did participate: the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, the National Nuclear Security Administration, the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) Glenn Research Center, the Army and Air Force Exchange Service, and Sandia National Laboratories. Here’s a look at the methodology and comparative results.

METHODOLOGY

Before contacting any federal agencies, we asked several experts to review the 200-question DiversityInc Top 50 Companies for Diversity survey to ascertain what was relevant to government agencies and what was not, as well as what should be added. These experts included: Gilbert Casellas, former chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and now vice president of corporate responsibility and chief diversity officer at Dell, one of DiversityInc’s 25 Noteworthy Companies; Weldon Latham, noted discrimination attorney and senior partner in the Washington, D.C., office of Davis Wright Tremaine; Barry Wells, first chief diversity officer at the Department of State and now U.S. ambassador to Gambia; and Dr. Henry A. Coleman, professor, Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, Rutgers University. We trimmed the DiversityInc Top 50 survey in half and modified it to reflect specific recommended changes:

Leadership Commitment We examined leadership instead of CEO commitment, with the focus on the head of the agency. We eliminated questions linking senior-executive compensation to diversity goals, since this isn’t relevant for government agencies, and instead focused heavily on the role of the department head-having the head of diversity as a direct report, having a visible quote on the web site, chairing the diversity council, making sure the agency’s mission statement incorporates diversity, and personally signing off on goals and achievements for supplier diversity.

Human Capital We included many of the same demographic questions we have on the DiversityInc Top 50 survey, looking at race/ethnicity/gender/age and programs to recruit and retain LGBT people and people with disabilities. As we do in the DiversityInc Top 50, we relied heavily on ratios that show progress, such as the comparatives of the current work-force versus new-hire demographics. We did include pay grades, both military and civil service. At the suggestion of the experts, we broke the data down into civil-service employees and political appointees. However, we found the six agencies that gave us data all submitted data for 99 percent or 100 percent civilservice employees, so that is what will be reported here.

Corporate and Organizational Communications This section closely follows the DiversityInc Top 50, as most of the areas addressed-diversity training, employee-resource groups, diversity surveys and communicating a diversity commitment on the web site-are applicable to federal agencies.

FINDINGS

Federal Agency Leadership As the chart on the previous page shows, the federal agencies participating all show strong leadership. However, there are a few areas where these federal agencies could improve, including having the agency head meet regularly with employee-resource groups (only three of the six do this), compared with 84 percent of the DiversityInc Top 50, and making sure diversity is incorporated into the agency mission statement (only three of the six do this), compared with 98 percent of the DiversityInc Top 50.

Agency DemographicsAs the next chart shows, the demographics of these six agencies exceed current U.S. work-force demographics for Blacks, Latinos, Asian Americans and American Indians. But these agencies clearly surpass most federal agencies, so we should not assume all agencies are at this level. We also note that the government agencies do not offer work/ life benefits as strong as the most progressive companies in private industry. For example, only two of these six federal agencies report alternative career tracks for parents or others with long-term family-care issues, compared with 62 percent of the DiversityInc Top 50 companies.

Agency Communications As we can see from the chart below, these six federal agencies have very strong internal and external communications of their diversity efforts and use their employee-resource groups as key sources of recruitment, retention and talent development.

Supplier Diversity As expected, these excellent federal agencies make a concerted effort to do business with minority- owned business enterprises (MBEs) and women-owned business enterprises (WBEs). So what can we learn from DiversityInc’s first survey of federal agencies? That very few of them yet excel at diversity management. We know a few others that are ahead of the game, and we’ll try to convince them-and others-to share their data and help improve our government agencies.

OPM official Griffin emphasizes workplace diversity

By Joe Davidson

As a woman who uses a wheelchair, Christine Griffin knows a thing or two about discrimination in the workplace. But now, more than ever, she’s in a position to do something about it.

Griffin is in her second week as deputy director of the Office of Personnel Management. Her boss, John Berry, has made her the point person to improve Uncle Sam’s record on diversity in hiring and promotions.

“I’ve done a lot of things in my life where women weren’t particularly accepted at the time,” she said during an interview in an office with pictures still unpacked. “I’ve certainly experienced discrimination and know what that feels like.” She has also been a “twofer,” someone who fills two demographics, acknowledging opportunities she was offered because someone “particularly wanted a woman with a disability in their workplace.”

Griffin brings more than gender and her wheels to the discussion. Her experience extends from the personal to the professional. A labor and employment lawyer by trade, until recently she was a member of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, where she wasn’t shy about criticizing the OPM. Before that she was executive director of the Disability Law Center in Boston. She is also an Army veteran.

At the EEOC, Griffin launched Project LEAD (Leadership for the Employment of Americans With Disabilities), which was designed to increase federal hiring of disabled people.

Despite that project and other efforts, Uncle Sam’s hiring of people with disabilities has been in a steady and disturbing decline. Every year since fiscal 1994, with one exception, the percentage of people with disabilities in the federal workforce has dropped, from a measly 1.24 percent to an all but invisible 0.97 percent in 2006, according to EEOC data. The next year saw a small increase, to 1.03 percent, but the percentage fell to 0.98 percent in 2008.

Latinos are also significantly underrepresented in the federal workplace. They account for 8 percent of Uncle Sam’s employees. In other cases, demographic groups may be well represented in the total workforce, but are too few in the upper levels of government. African Americans, for example, are 18 percent of the total workforce, more than their percentage in the general population, but hold just 6.7 percent of the jobs at senior pay levels. Women, representing 44 percent of the workforce, are 27.7 percent of those who make the big bucks.

Griffin joins the agency as it prepares an overhaul of the government’s defective hiring process. At “every avenue into the federal government,” she said, “I want to make sure that we’re also talking about how to increase diversity.” Griffin said agencies should do some introspection and look at their unintended barriers to hiring and advancement. “What is your particular area where you are lacking in advancement for people, and opportunity for people to come in the door, and why is that?” she wants them to ask themselves. “Start doing some barrier analysis.”

Too many agency officials regard that kind of activity as time-consuming work that doesn’t rise to the top of their priority lists. Instead, it needs to be part of their strategic plan “to be the agency of choice for people who have the skills that I need,” Griffin said. It’s “getting off your butt and going out there and making people know that you really do want to cast that wide net and get people in the door.” Griffin is praised by people who have worked with her on improving diversity.

“I would give her high marks,” said Jorge E. Ponce, co-chair of the Council of Federal EEO and Civil Rights Executives. Her new position provides “a wonderful opportunity,” he said, for the EEOC and the OPM to better coordinate their activities. In 2006, the Government Accountability Office “found little evidence of coordination at the operating level between EEOC and OPM in developing policy, providing guidance, and exercising oversight, despite overlapping responsibilities in federal workplace EEO. . . . Good management practice as well as federal statute and executive order call for coordination, and not doing so results in lost opportunity to realize consistency, efficiency, and public value in EEO policy making and oversight.”

Ponce said it is unrealistic to think that the government “cannot find Hispanics with the citizenship and educational requirements to be better represented” in the federal workforce.

To make diversity a greater priority in the government, Berry created an office within the OPM to focus on it. A diversity professional “is going to look at government-wide diversity strategy . . . to create a more diverse workforce,” Griffin said. “That’s a concrete thing that has been done.”