“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

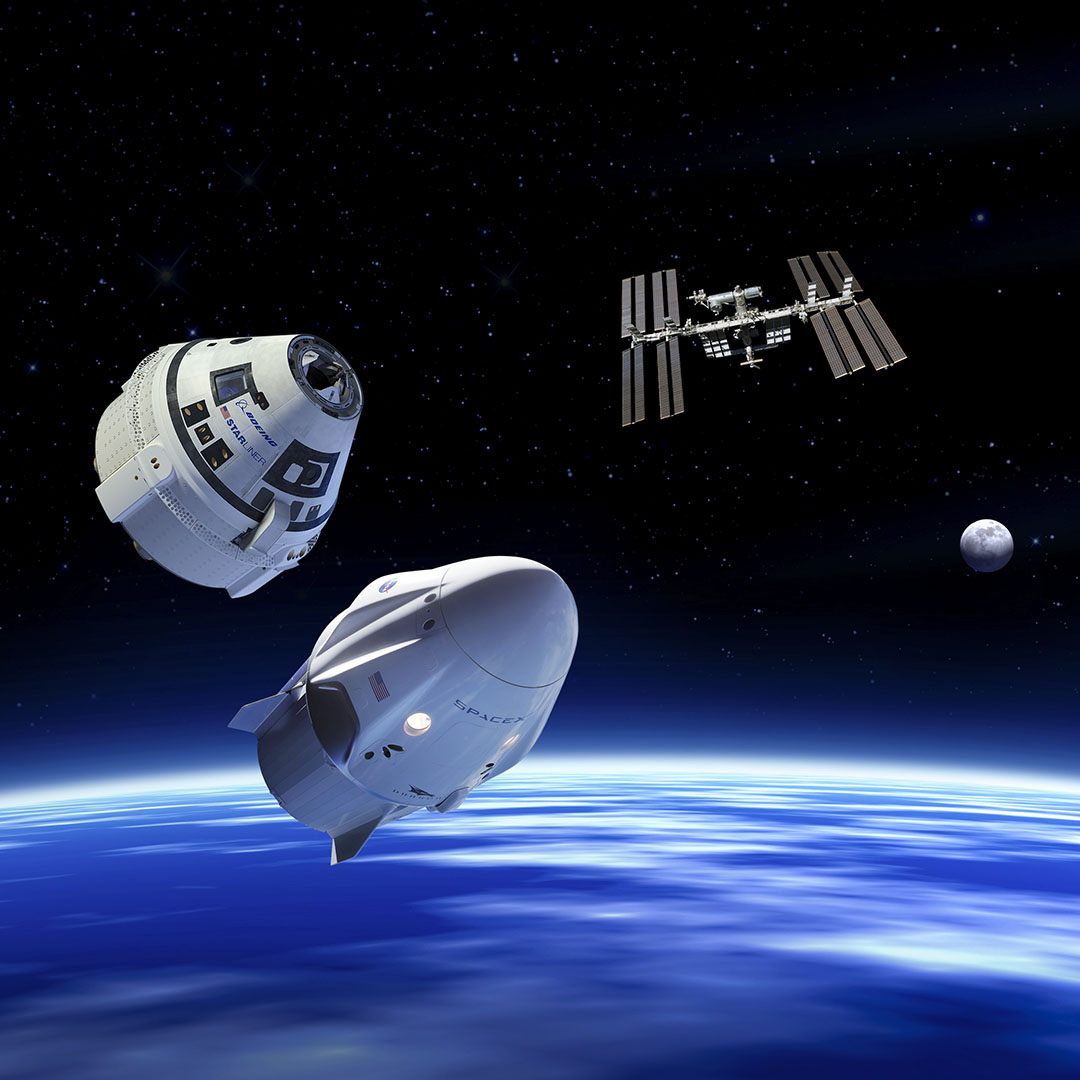

On Episode 80 Steve Stich, Deputy Manager for Commercial Crew, discusses how we are once again launching astronauts from American soil. Stich talks about the astronauts flying in the commercial crew spacecrafts, the upcoming test missions, and the role of private industry in the future of human spaceflight. This podcast was recorded on December 14th, 2018.

Transcript

Pat Ryan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center. This is Episode 80, From American Soil. I’m Pat Ryan. I’m your host today. This podcast brings you the experts from NASA, scientists, engineers, astronauts, other leaders, to tell you the coolest parts about what’s going on at NASA. And today, we’re talking again about launching astronauts from the USA. U-S-A! With two different vehicles that are being developed by two private companies, Boeing and SpaceX. They are part of the commercial crew program that’s designed to enable the capability of launching people into space by private businesses. Now, earlier in the podcast, we had an opportunity to talk with the commercial crew program manager, Kathy Lueders, about the overall program history and progress. Today, we’re joined by Steve Stich. He’s the Deputy for Commercial Crew based here at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. We’re going to talk about the crews for the very first missions that have been announced. Also, talk about how these crews are working with the companies to design the vehicles. We talk about the upcoming test missions and what happens after that, how the commercial crew program that’s enabling some of these milestones is playing a huge role in the future of human spaceflight by private industry.

Now, a couple of quick notes up front. We recorded this interview on December 14th of last year, 2018, so when you hear us make any reference to something happening next year, that means 2019, this year. And second, a note about references to astronaut Eric Boe. He was one of the first four astronauts assigned to the commercial crew program back in 2015 and has worked with the private companies to help develop the vehicles, as Steve Stitch will mention. Now, Boe was assigned to fly the first crewed mission of the Boeing Starliner, but in January 2019, he was removed from that assignment for medical reasons and has taken over as the assistant to the chief of the astronaut office for commercial crew. He’s swapping jobs with astronaut Mike Fincke. Fincke has been added to the crew for the Boeing Starliner crewed flight test later this year. Like Boe and other CCP astronauts, Fincke attended test pilot school and worked as a flight test engineer during his career in the Air Force. So, let’s get right into it. We’ll jump ahead to our talk with Steve Stich. Enjoy.

[ Music ]

Host: Steve Stich, thank you for coming and joining us today. It’s a pretty exciting time at NASA and at really, the whole human spaceflight program. We’re getting ready to launch people to space from the USA. There are two commercial crew vehicles in work, astronauts getting ready to fly in both of them. Let’s talk about the astronauts, let’s start there, because that’s what, I think, people connect with the most. Tell me about that the human beings who have been assigned to do the first flights on these two vehicles.

Steve Stitch: Okay. Well, first of all, thanks for inviting me today. It’s great to be here and, as you said, it is a very exciting time in commercial crew, and getting ready for these early crewed flights. You know, recently we named the crew members for all these flights, so from my perspective, once you name crews, it starts to become a lot more real. You know these flights are going to happen. So, you know, we’ve had Doug Hurley, Bob Behnken, and Suni Williams and Eric Boe with us a since 2015. They were named as the cadre to help develop the vehicles, to help make sure crew considerations were are at the forefront of the development of these vehicles, and so they have been in on all the testing of displays and suits and so forth. But then recently, you know, we named for the first Boeing crewed flight test Eric Boe, Nicole Mann, Chris Ferguson for that flight, and then for this first SpaceX flight, Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken, and they’ve been working that vehicle for a long time zone.

So, those crews were named, and now instead of working together as a cadre, before they were working together on both vehicles, so those first four were working on both Boeing and SpaceX. Now, they are very much divided, and the Boeing crewmembers are working the Boeing test flight, and they’re starting to train, and still do display development and those sorts of things.

Host: And, there are astronauts assigned to the second flight of both vehicles.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. Absolutely. So, for the first what we call post certification mission, or truly that first Boeing mission that will support the space station increment, we have Suni Williams and Josh Cassada assigned to that flight, and then Victor Glover and Mike Hopkins for the SpaceX, the equivalent SpaceX flight, which is really the purpose of the commercial crew. You know, we have these test flights, we have uncrewed and crewed test flights, but really, our overall mission is to support the space station program in the increment to deliver the crew there, for the vehicles to stay for that increment, and then to bring the crew home at the end of the increment.

Host: Because it’s always been part of the program with the space station, that for every crew member on orbit, there has to be a way to get off right away.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Host: And so, if we were going to send more crew, expand the crew to do more work on orbit, there has to be a way for them to get there and for them to get home. And, these two vehicles are designed to fill that role, right?

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. Absolutely. The Boeing Starliner and the SpaceX Dragon are designed to be that transportation mode, almost like a taxi to take you up and return you, but also if something were to go wrong with the space station, whether there would be a medical emergency or some other reason for the crew to leave space station, that vehicle has to sit there, be on-station and be ready, and we actually have in our requirements it has to be available for up to 210 days. So, that’s the design requirements. All the vehicles are designed to be there for 210 days to serve as this lifeboat, and we hope we never have to use that, obviously. You hope you never have to evacuate station or ever have a medical reason to return a crewmember, but that’s part of the mission, so.

Host: And that about the same length of time that the Soyuz vehicles are—

Steve Stitch: It’s very comparable to Soyuz. Soyuz today stays, you know, six months, maybe a little longer, maybe a little less, depending on their commitment, but these vehicles are really designed to sort of be that Soyuz replacement from a US perspective.

Host: Let me take a step back, in case this is a question that people don’t know the answer to. Why has NASA decided to work with these private companies to have them build their own vehicles to go to the Space Station instead of NASA making its own?

Steve Stitch: You know, I would say these commercial vehicles are sort of a follow on to the cargo, the cargo program. So, several years ago, you know, in 2008 we started the COTS Program, and then that led to the commercial resupply contracts for SpaceX and Orbital to take cargo back and forth to the Space Station. And then, that worked out pretty well, and people started looking, as the shuttle was retiring, what would be a good mechanism to take our crews to the space station and return them? And, this idea of having commercial companies provide this service sort of arose from that early cargo days, leveraging that work, and taking advantage of the launch vehicles that are flying today. And so, it just seemed like a natural follow on to cargo and having the companies provide this service to NASA. So, unlike other programs like Apollo or space shuttle, NASA doesn’t own the vehicles, per se. They are not owned by the government. We contract for a service and for the companies to deliver the crew and then some cargo and return the crew and cargo, and so it’s this unique relationship. And it gives the companies the opportunity to take these vehicles and then broadly expand this commercial enterprise of space, you know, for a long time it’s been only the US government that’s been sending people to space. But you can envision in the future, you know, there’s a role for companies to provide other people into space, and even commercial space stations, if you will. So, it’s trying to facilitate and expand this whole commercial endeavor in low-earth orbit.

Host: And, that’s even part of the International Space Station’s mission is to help develop the commercial space flight, as well as the commercial use of space, commercial research in space, so this is an extension of that same goal of the agency, is in order to work with private companies.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, absolutely. If you look at the space station today, you’ve got all kinds of companies that are flying their payloads, going through a safety process for their own needs on space station, you know, we deploy little CubeSats out of the space station. We do all kinds of experiments and research for the medical industry and other industries to further their, and, you know, it’s really, they have the business model. It’s not NASA as much deciding whether we want to fly a payload or not. They propose their experiment, we provide them the ride on the cargo vehicles, and then we provide them power and data on space station, so it’s almost like a perfect marriage, if you will. You have this great laboratory.

Host: Yeah.

Steve Stitch: How do you take advantage of it? Are we in the government the only people that are smart enough to figure out what the right experiments are? No, you offer it to industry and you really have this kind of burgeoning commercial space sector, if you will.

Host: Yeah. I don’t want to go too far down that rabbit hole, but let’s get back to, we were talking about the crew members that had been assigned for the first Boeing flights and the first SpaceX flights. Give me a sense of what they’ve gone through to get prepared. You mentioned how the original four commercial crew astronauts were involved with both companies in trying to—of being the human—what is it? An avenue for the human input into the development of a brand-new spacecraft. Now that there are more and they’re assigned to specific vehicles, what sort of work are they doing right now? What kind of training are they involved in to get ready for that first flight?

Steve Stitch: Yeah, so they really have a twofold, first of all, they’re all test pilots, so they all have this test pilot background, so they know what it’s like to develop a new system and deploy it from a test pilot perspective. So, they’re still helping the companies, you know, refine cockpit layouts and displays and things like that from a test pilot perspective, but they’re also, knowing they’re going to fly on that vehicle, they’re also doing training, so they’re doing simulations and practices of how to do the launch phase and what kind of aborts you would do in that phase if you had to have an abort. How do you do the rendezvous on approach? How do you live in the spacecraft? How do you do docking? How do you monitor the automated systems? These vehicles are very, when I look back, I spent many, many years in my career working shuttle. Shuttle, the cockpit had switches everywhere, it’s back from the 70s. Well, these vehicles, if you go in and look, there are some switches, but it’s mostly automated, it’s mostly a software screen interface, kind of how as the modern world has adapted to where computers and displays and that kind of technology is there.

So, how do you monitor that technology, how do you deorbit from the space station, how do you undock, how do you land? So, they’re working through all those things. And then contingencies, you know, how do you get out of the spacecraft, if you have a landing that a little off nominal? How do you get out if you land in the water? You know, SpaceX plans to land in the water for every flight. Boeing has the ability for aborts to land in the water, and then they plan to land on land. All those contingencies. They’re also working on the space suits, and the space suit development, we mandated that you had to have a launch and entry suit to protect the crew, should, you know, you have any off-nominal situation during launch, and so they’re testing the suits. How do the suits work with the seats, displays, all those kind of things that are very crew-specific, even the details of where to put, you know, they have instead of a lot of paper products, they have an iPad for procedures or a kind of a tablet. Where do you put that? How do you work with those tablets? All those kind of things, all those details that you really need as a crew member to go fly successfully.

Host: It seems like it’s, in one sense, it’s not different, really, from the way astronauts used to train to fly in space shuttle missions, but what is different is, nobody’s ever done this before. And they’re, in a sense, I guess, help developing the procedures for how these missions will be flown.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, right. I mean, in early days, you know, the early shuttle crew members, Bob Crippen, John Young that were in the middle of developing procedures for shuttle, and now for these vehicles we have our astronauts now in the middle of that procedure development helping the companies with that, based on their, many of them are experienced shuttle crew members, and they’re helping the companies on how you develop those procedures, and how they want to lay it out, and how they want to do it. So, it’s pretty exciting for a crew member, too, because they are kind of writing the book on how those first flights are going to be flown. You know, a lot of us came into shuttle later, after it had been flying, and a lot of the procedures and the vehicle was developed. Well, now you’re doing it all from scratch, and while the vehicle’s being built and tested, which is pretty exciting, actually.

Host: Yeah, for it to be, to be doing something brand-new, be in on the ground floor.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, for me personally, I mean, I’ve been at NASA quite a number of years, over 30, and then, you know, it sort of re-energized me. As you work with two different companies, different approaches to building two different vehicles. It’s exciting, because the vehicles have the same requirements, but each company did it a little differently. And so, you get to work and understand why each company chose different paths, and so it’s a lot of fun.

Host: In terms of the training itself, where do the astronauts do that work? Is it here in Houston, where they live, or in the company locations elsewhere?

Steve Stitch: So, that’s a really good question. So, the training is a little different for both companies. For Boeing, the Starliner training is done here, actually, at JSC. So, there’s a mission simulator over in building 5, just like we had for shuttle. They do a lot of training there, and then there’s a mockup over in our building 9, and they can go in and practice different things in both those facilities. And, obviously, there’s a component of space station training that’s done, obviously, here in Houston. For SpaceX—

Host: Because they are going to the space station, these astronauts that we’ve talked about.

Steve Stitch: They’re going to the space station. So, there is some amount of space station training that they’re getting, because there’s going to live on the space station for a period of time while they’re going to be there. Obviously, the crews we talked about for those increment missions, they’re going to be there, most of their time’s going to be spent on space station for these test flights, you know, we dock for a week or two and then come back home. So, they do station training here. And then, SpaceX, it’s different, the training is actually at Hawthorne.

Host: That’s in California where—

Steve Stitch: In Los Angeles, it’s very close to the Los Angeles International Airport, and they have a simulator there. They have a mock up and simulators there, so the crews fly there to do display development and training there, and the space suits are there at Hawthorne. And so, it’s a little different approach, you know, Boeing has chosen to do it here in Houston, and SpaceX has chosen to do it at Hawthorne.

Host: And, just because I’m just thinking of it, both of these vehicles plan to launch from Florida.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. Both vehicles are launching from Florida. The Starliner launches from the Atlas launchpad 41, and then SpaceX is planning to launch from the old shuttle launch pad, 39A, in Florida. So, they all start at kind of the same place in Florida, and, you know, they end up landing in different places, and then the training happens in different places, so.

Host: And, they land in different places. You mentioned before that SpaceX, like their cargo vehicle, this would land in the ocean.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. So, SpaceX’s plans are to land just off the coast of Florida near the Kennedy Space Center. That’s their landing point that they prefer. For later missions, they’re also looking at another Gulf of Mexico landing site, as well, but they really like to land just off the coast of Florida, and then they can bring their capsule back, tow it back in, and take it back to the hanger and refurbish it there. Boeing’s got a different approach, and so if you look at the SpaceX capsule, it kind of might remind you of, like an Apollo water landing. Boeing’s approach is different. So, Boeing has chosen, and SpaceX has chosen to build a new vehicle for us. For every flight, we get a brand-new capsule, because it lands in water, just like Apollo. Boeing has a reusable spacecraft approach, so their spacecraft, they’re going to land on land, and they’re using two landing sites that are somewhat familiar to many people, the White Sands Missile Range, or an area called the White Sands Space Harbor, which we used for a backup shuttle landing.

Host: In New Mexico.

Steve Stitch: In New Mexico. It’s near Alamogordo, New Mexico. And then, Dugway Proving Ground is another, in Utah, is another primary landing site for Boeing. And then, they’ve got a few other ones. Edwards Air Force Base is one. So, these sites are, you know, for landing a capsule, you need a site that’s a big, open area where you can safely land and not have any terrain that’s going to impact the landing, and then, you know, parachutes get deployed at different stages and end up on this open area, and so you have to kind of have a big area to land in. And then, Boeing uses airbags to cushion their landing, to land on land, which is a little different technique. And so, they would then, you know, have a crew out there at the landing site, get the crew out of the vehicle, get the cargo out, and then tow the vehicle back to Florida. Both, all the final prep for the launches also occur in Florida in different locations, at the Kennedy Space Center and then over on the Air Force side.

Host: We touched on this a minute ago, and I’d like to get you to tell me a little more about the missions, themselves, these first test flights. I think, even for me, I work here, and I’ve been aware of commercial crew, but I went for a long time not realizing that these first test flights were going to go to the space station and then we’re going to dock to it. Tell me about, in the case of the first, let’s start with the first test flight that don’t have astronauts on them. What’s the profile of that mission? What’s going to happen? Where does it go and do?

Steve Stitch: Okay. Yeah. All these test flights are really testing out all the key parts of the mission that you need to be ready for crew, and then be ready for these longer missions on the increment. So, start out with a launch, we’ll just talk Dragon. Starliner is exactly the same, but start out launching from the Kennedy Space Center. We’ll launch, go into orbit, and then start executing a series of rendezvous maneuvers. First day, we kind of check the vehicle out, make sure all the sensors are working right, the docking system is working, and then the rendezvous day can be kind of what I would call the second day of the mission, in terms of a crew day that we’re used to, or the third day. And it will go up and start to use its rendezvous sensors to acquire the space station when you get in closer, and then fly a corridor in and then dock to the space station. And so, that test, all the key parts of the vehicle, if you think about it. We’re testing the launch vehicle, separation, flying in space, doing navigation in space, all the systems that you need to keep the crew healthy and safe. And then, all the rendezvous sensors, and then in on the docking, to test all those systems out before we put a crew onboard, and then, you know, depending on the mission, we can stay up to 30 days. Most of the companies would want to stay between seven days to two weeks. And we work with the space station program on how long is that dock duration going to be, because they have a lot of traffic.

Host: How it fits in to whatever else is going on.

Steve Stitch: How does this fit into the cargo delivery missions, or Progress, or the international partner vehicles, ATV, HTV, vehicles coming up to the space station? And then, stay there for some number of days, open the hatches, we’ll have some cargo on these vehicles for the space station program.

Host: Don’t want to waste the opportunity.

Steve Stitch: Right. And, also, it’s a down mass opportunity to return science, as well. And then, while it’s docked, you know, we use the space station, obviously, the crews won’t spend much time in these vehicles once you’re in increment. They’re on the space station and you’re only going to use this return vehicle if you need to for an emergency or the nominal landing. Test that the systems talk to each other, that space station could talk to the crew vehicles, that we can exchange airflow and keep the air condition in these vehicles. And then, there’s some flight test objectives that each company has. They’re going to look, also, at the engineering performance, you know, how do the heaters perform, how do the systems perform? We get a chance to—

Host: See if everything works the way it was designed.

Steve Stitch: Exactly. We get a chance to power some boxes, some part of the avionics system gets powered down to save power. Space station provides power to the vehicle, so we’ll test that, and then when we get through all those tests, we’ll test the undocking and maneuvering away, sepping from the space station and then executing the deorbit burn, going through the reentry time frame, parachute system, landing, recovery of the vehicle. So, it’s kind of an end-to-end test of what it would be for the crewed test flights without the crew, and so you’ll get a real good check out of the whole vehicle.

Host: And it sounds like that could be anywhere from maybe just a week to maybe almost a month.

Steve Stitch: It could be a week to a month. We’ve told the companies, Boeing and SpaceX, hey, we really need flexibility, so these early flights, let’s plan for up to 30 days, knowing the vehicle is designed to be there for much longer, but they’re planning for that, and so we have that flexibility to determine the mission duration when we get a little closer to flight.

Host: Yeah, you start adding in more, you know, two more lines of vehicles that could be coming, and you start to have a traffic jam around the International Space Station.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. And, it’s something that the station program manages well every day, and they’re excited about having these two new US vehicles to manage the traffic flow.

Host: When we get to the first test flights of the two vehicles where there will be human crew members on board, is it essentially the same kind of profile as the uncrewed flights, or is there some other special, cool aspect added to that?

Steve Stitch: No, both vehicles will fly the exact same profile, and largely automated. You know, they both have to keep the crew healthy, and so that aspect’s a little different, you know, waste management and hygiene and how the crew will eat and sleeping and all that. But, you know, if you kind of have those two flights side by side, you were comparing the trajectory, for the most part, they’re going to look very much the same. And so, we really want to test out the systems in this uncrewed manner, and both companies proposed this to NASA when they submitted their proposals, and we accepted it and thought it was a really good idea to, and, you know, you learn everything, every time you fly a flight, especially with a new vehicle. So, we have an opportunity to learn from these two test flights and then fold that into the crewed flights and make improvements where we need to.

Host: You learn all the things that you don’t yet know you don’t know.

Steve Stitch: Correct. With every new vehicle, you know, my experience has been, there’s something that doesn’t go maybe as planned, and so you can go back on the ground and fix that, whether it be a slight software problem, or some problem with the system. So, that’s why it’s really a good approach for a commercial crew. We can learn with these partners, and then, it gives you a sense of comfort for the safety for the crew when you go through a test flight and you prove out the vehicle in an unmanned configuration, and then come back and do it with crew.

Host: So, on the first test flights for each vehicle, we’re still looking at them only being at the station a matter of a couple of weeks.

Steve Stitch: Correct.

Host: Do they have space station responsibilities when they get there?

Steve Stitch: They don’t become expedition crew members, per se, because they haven’t quite received all the training. They receive safety training, but there are certain things they can help the space station increment crews with, certainly cargo logistics of loading and unloading, and there’s probably some things on station they can actually help with. Some of them have spent time on station, so they can be fairly helpful, but they’re not, their focus and their training today is really understanding and knowing these vehicles inside and out for these first flights.

Host: Yeah and those first two flights, what is that, four of the five crew members have all been to the space station before on shuttle missions.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, absolutely, and it’s actually five when you include the Boeing, Boeing has three. Chris Ferguson’s one of the crew members as well, so.

Host: Yeah, four of the five.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Four of the five have been to the space station, so they can, yeah, they can actually help out, they’re kind of an extra set of hands, if you will, while they’re there. And, they have to learn a little bit about space station, you know, the hygiene systems on space station, food and so forth, and so they get that training, as well.

Host: But, they’re there primarily to be focused on testing out their vehicle and the shakedown.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. Absolutely. It’s a shakedown test flight, and so the priority in all their training is really understanding these vehicles, and so that’s why, you know, many of them were signed as part of the cadre that got to work with the companies inside and out when they were designing the vehicles, and watching them kind of grow up from just, you know, a few parts to now, spacecraft. And now, they can get in them and fly them, fly these test flights.

Host: See the system that they tried to help design.

Steve Stitch: They can see the systems that they, their handiwork was involved in actually helping put the systems together.

Host: So, then the question becomes, what’s the significant difference, I mean, you take what you learn on those first crewed flights and fold it back into the system and make any changes that you need to make. What becomes different, then, for the second set of test flights, what they call the post certification missions?

Steve Stitch: Yeah, so those I wouldn’t consider test flights, right, so got two test flights for each. We’ve got an uncrewed test flight and a crewed test flight.

Host: Right.

Steve Stitch: And then, we move into these post certification missions, and that’s where things—

Host: And, I guess it’s the first flight that leads to the certification.

Steve Stitch: Well, post certification really means the vehicle has been certified after these two test flights, and then we’re ready to do the mission, and the mission really is supporting space station. So, having a vehicle that can transport four crew and some cargo, and including returning some powered cargo for the space station program, and then having that vehicle serve as a lifeboat. So, we really want to test them out twice, once uncrewed and once crewed, and then, you know, our overall objective is to then have these vehicles be ready for these regular increments that the space station program needs. So, at that point, you know, every flight you’re learning still. My experience in human space flight has been, it’s just a complicated business, and you always want to be looking at what happened in the previous flight.

Host: Sure.

Steve Stitch: Looking at all the data.

Host: You do that with machines on earth, too.

Steve Stitch: We do that, right, right.

Host: They always show you something about themselves that you didn’t know.

Steve Stitch: Right, and these vehicles, you know, human space flight, the systems are complicated and both companies do a great job of putting together these complicated vehicles. But we’ll always be watching and learning and looking at the data and making sure it’s performing the way it should. So, we’ll always be learning, but when we get into these post certification missions, it’s really for space station.

Host: Yeah, now it’s official. We’re really in business.

Steve Stitch: Exactly.

Host: So, that means, how long would they be? How long, instead, will they still be only a week or two or 30-day missions, or would they then become longer?

Steve Stitch: No, these post certification missions can be whatever the station, the vehicles would be certified for this long duration.

Host: So, they could be six-month flights.

Steve Stitch: They could be six-month flights, and we will, depending on when these missions fly, we will work with station to figure out how long they should be, because they have to work into the station rotation, and so.

Host: Right. And, you mentioned a second ago that each of them is capable of bringing four crew members to space. There’s only two assigned to each one, so I’m guessing you’re going to fill those other seats.

Steve Stitch: Yes, yes, those other missions will get other crew members assigned. The two that are assigned to those currently are really, you know, if you will, the pilot and the commander, the people that would be responsible for flying the vehicle, and then we’ll have two more mission specialists that gets assigned later on to fill out that complement of four for the space station increment need.

Host: But, all four of them would then arrive at the station and become space station crew members.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. At that point, they become space station crew members, and those crew members are trained on the vehicles, but they’re also trained to do the task on space station that they need to do.

Host: So, it’s similar to the current crew members, who are also trained on the vehicle that they ride up and down, in this case, the Soyuz. These crew members will be trained on their Starliner or their Crew Dragon, as well as on all of the regular things that station crew members are trained on.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, absolutely. They’ll get a little different version of training, you know, the crewed test flights, they’re going to get a little bit of space station training to do the things you need to do, exercise, hygiene, use the potty on space station, if you will. But, then these other crew members for Boeing and SpaceX, Suni Williams and Josh Cassada and Victor Glover and Mike Hopkins, they’re going to be part of an increment that’s going to stay on the space station for however long the space station program needs them to stay, so.

Host: And, at the time they fly, they will have two additional crew mates who will also become station crew members.

Steve Stitch: They will have two additional crew mates assigned to those missions, just like, you know, every, most Soyuz today have three, sometimes two, but you’ll have that increment crew.

Host: And, that’s the point, right? By the time we get to there and these post certification missions are flying, we’ve added this new conduit for supplying the space station with crew members and with cargo.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely.

Host: Up and down.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. And, we’ll have the ability to add an extra crew member. Today, Soyuz can fly three. We’ll have a fourth crew member, and the idea behind that was, you know, we’ve got this great, if you look at what is the limiting factor sometimes in how much science can get done? It ends up being, it ends up being crew time on orbit. So, if you add an extra crew member, you can get more science done on the space station, can accomplish more research, and that’s one of the goals of our program is to sort of expand the amount of research that can happen on the space station.

Host: Just, in my head, I’m thinking, you know, theoretically, all the tasks that need to be done to maintain the station are already being done among the five or six crew members who are there now. So, anybody else that you add is 100% other stuff, where the hours may be broken out amongst other people, but you’re adding that many more man hours of capability to do other things.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, absolutely. You subtract out the amount of time they need to sleep, and take care of, eat, and do those sorts of things, that extra time they have is really, you know, free time to do science, because you’re right, the space station today is maintained by a crew of six, and so you’re adding an extra US crew, or USOS crew.

Host: The science office in the space station program must be beside itself about the prospect of getting that much more time.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, they can’t wait to have these vehicles and have that extra time, and they also can’t wait to have a little more cargo up and then an opportunity on a more frequent basis to return cargo.

Host: Right. Right now, the only way they’re really getting it down in any quantity, in any serious quantity, is on the Dragon cargo ships. They get a little more on Soyuz, but this would allow a lot of science to be returned to the scientists to do their, to continue their research.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely, and it gives you another opportunity to return that science, a little bit more science, because you’re right, today we rely very heavily on Dragon to return all science, and you do get a little bit in Soyuz, but they don’t have the capability to return a lot. So, we have couple powered payloads that can return scientific samples that are, you know, in a cool environment, and we can bring them back on our vehicles, and that was a requirement from the beginning. Station one had the ability to launch that cargo and also return that cargo.

Host: You said a minute ago that the traffic pattern, if you will, would then become, I guess, the purview of the space station program. Here’s what we need, and here’s where we can fit it in. Do you guys have any sense at this point of how frequently then down the road these vehicles may be flying?

Steve Stitch: Yeah, we’ve been working with the space station program, and we really have the vehicle set up to fly. Each company have a vehicle ready. One vehicle per year. So one Boeing flight per year, one SpaceX flight per year. In fact, those missions are actually on the contract today, so they already have three flights on contract, so if you think about SpaceX, they right now have an uncrewed test flight that they’re working on, going to launch very early next year, a crewed test flight, and then they have three of these station missions on contract. Same thing for Boeing. They have those five flights, and so, you know, if you look at vehicles in flow, if you go down to the Kennedy Space Center, for example, and look at hardware for the orbital flight test for Boeing, all the hardware is there. The Atlas launch vehicle is already there being processed by United Launch Alliance, and the vehicle for that flight is being built in the crew and cargo processing facility. That used to be the old orbiter processing facility three, and then for SpaceX, the launch vehicle for demonstration mission one, which will fly early next year, is there, and both the first and second stage are there for that Falcon 9 rocket, and then the Dragon capsule is there, both, it has two parts, the trunk and the main part of the vehicle. It’s already there. If you went to other places around the country, you’d see the other pieces in flow, and for Boeing, the service modules are, Boeing has a crew module and a service module, much like Apollo. Those are starting to be built and assembled there at the C3PF, and SpaceX has also their crew Dragons. You could see the crewed flight test vehicles there at Hawthorne, and then this first increment mission’s vehicle is there at Hawthorne being built. So, lots of hardware all across the country. It’s really an incredible time to be part of this program.

Host: You mentioned acronyms, and you just flew one by me that I don’t want to let go unremarked upon. The C3PF, he said?

Steve Stitch: Let’s see. C3PF, and I’ll have to think about what this is, now, but the Commercial Crew Processing Facility.

Host: Processing Facility I guess.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Host: That’s clever.

Steve Stitch: Yeah. They, you know, there’s a little marketing toward all these things, and, of course, it wouldn’t be NASA without me throwing out an acronym. I try not to, but yeah, so that’s where Boeing’s assembling their vehicle. It’s in Florida, so, leveraging facilities that were there for space shuttle, and now repurposed for commercial crew.

Host: If each company is planning to fly once a year, are they, like, offset by six months, so that?

Steve Stitch: They would be, they would be. There would be one vehicle, you know, flying in the first part of the year, and another in the second six months of the year, if you think about these six-month missions, and we kind of have to orchestrate how those fly with space station, so we’ve had to put these things on contract, and have these vehicles being built up to support the mission needs—

Host: Right.

Steve Stitch: Of the space station program.

Host: But then the four crew members replace four crew members, and it keeps the crew complement up.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. That’s the concept, right? This would be the one line, there will still be a Soyuz line going up.

Host: And, I was just about to go there. This is not meant to get rid of Soyuz as a means of flying to the space station, right?

Steve Stitch: No, we’ll still have Soyuz missions, and we’ll still have a complement of crew members, you know, flying that increment on the Soyuz, and then we’ll have another complement of increment crew members flying on the US vehicles, so it’ll be a little, it’ll be a little different, since Soyuz has been doing all the crew rotations for some period of time, but now there will be a US vehicle and a Russian vehicle doing those crew rotations.

Host: Does it move all the American astronauts onto the American vehicles?

Steve Stitch: No, there will still be American astronauts.

Host: On Soyuz.

Steve Stitch: The plan is to fly them on Soyuz, because they’re flying up as a team. Think about, you know, this increment crew, they were there together, there’s always been a US crew member as part of an increment, and the same thing with the Russians, and so we’ll just have to work out who flies on what vehicle.

Host: So, there could be astronauts from other nations’ agencies that will fly on the American vehicles.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely. That’s been the whole, that’s been the whole point of the program. In fact, we have been sharing data with international partners on these vehicles, and we have meetings to explain how the vehicles work, because their astronauts literally are going to fly on these vehicles.

Host: Sure. Up until now, the station has been coordinating the efforts of space agencies from different countries. Now, it’s going to have to also work in coordinating with these two companies with their own vehicles, too. For instance, in terms of mission control, do Boeing and SpaceX set up their own mission control center and operate when their vehicles fly?

Steve Stitch: That’s a really good question. So, the answer is yes, for the vehicle flying up, each company has their own mission control for that vehicle. So, in the case of the Dragon, that mission control center is actually out at SpaceX in Hawthorne, California, which is, as I said, close to the LA airport, international airport, and so the flight will be flown from there. Their launch control is actually going to be at the Kennedy Space Center out of an old shuttle-firing room. Boeing actually has mission control here in Houston, in building 30 where.

Host: Here at the Johnson Space Center.

Steve Stitch: At the Johnson Space Center, where, you know, the, gosh, Apollo missions were controlled from, all the space shuttle missions were controlled from.

Host: Back to Gemini Four, I think.

Steve Stitch: Apollo, Soyuz, back to Gemini Four, Six, I’d have to go look. Yeah.

Host: Somebody’s already looking it up and telling us.

Steve Stitch: So, Boeing would, yes, yes, so, yeah, Boeing would use that control center, and the Boeing flight control team would be here in Houston, and there’s still an ISS flight control team, you know, controlling the space station, and so now that team gets to work with two new control centers, right, just like when we worked space shuttle missions, the space shuttle flight control team and the ISS team had to work together to bring the two vehicles together and exchange the right data.

Host: And also worked with the Russian flight controllers.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely, absolutely, absolutely.

Host: And perhaps European or Canadian controllers.

Steve Stitch: So, we have two new, you know, we’ve been integrating the cargo vehicles, each cargo vehicle on the US side has their own control center, and so they’ve been integrated into the space station flight control team. So, this is just two new vehicles, and so it’s pretty exciting, and I’ve gotten to participate in simulations. You know, we have a mission management team, and so we’ve been practicing that, in addition to getting the vehicles ready and working with the flight control team, and we throw in anomalies, and how are you going to disposition those, and how you going to work the launch countdown and giving the go for launch? And so, we’ve been doing that in parallel with getting the vehicles ready and getting the crews trained so, you know, when you add all those things up, it’s a pretty exciting time frame.

Host: Yeah, it sounds, in some respects, as though integrating Boeing and SpaceX’s operations is not too different than integrating the operations of another space agency in the partnership. It’s just, it’s bringing in another company with its own, it’s contributing its own hardware and has its own interests in how it goes, and they have to work together with everybody in order to make one program work.

Steve Stitch: Yes, yeah. I mean, integrating those flight control teams has been pretty easy, because, you know, we’ve, I would say we’ve figured out how to do that over 50 years of US space flight experience, and so it’s pretty easy to integrate another team in, and figure out how to exchange data, and how to track the vehicles, and how to work together as a team. And there’s flight rules and procedures, and so the ops teams, you know, I was a flight director at one point, and I’m not heavily involved in ops these days, but you can just see that it’s very similar to what we did for space shuttle or other programs. And so, it’s pretty exciting to do that and watch the teams train and get ready and, you know, throw in the malfunctions.

Host: I’ve heard that some of those simulations, they’re starting to happen around here more frequently.

Steve Stitch: They are, I mean, we just did a sim with Boeing this week, actually, where we practiced a launch, starting at launch and going all the way through docking, and reviewing all the systems to make sure at the mission management team, we would be go for docking, and we had the space station program part of that, and we stimulated a practice MMT for Starliner, and one with the International Space Station Mission Management team.

Host: Right.

Steve Stitch: Went through that whole time frame. It was a long day, which is great, because in some ways, you know, if you think about our ultimate goal is to be doing this for real, and so it’s exciting to be practicing that in the middle of all the other development that we’re doing.

Host: You mentioned that the current contracts with the two companies are for three, if I can use this, you tell me if it’s wrong. Three operational missions.

Steve Stitch: Correct.

Host: After you get done with the test, you get three operational missions. Do we envision that Boeing and SpaceX would continue this into the indefinite future?

Steve Stitch: Yeah. We have awarded three for each. There’s actually six on the contract, so they each get six missions, and as long as space station is there, however long the life of space station is, we envision these vehicles, you know, flying up and serving as the transportation vehicle and then the lifeboat, and we just have to make sure station gets extended, when we look at the lead time required to build the vehicle and get the launch vehicle ready, and then, yeah, we could continue to serve this function.

Host: From NASA’s point of view, it’s not a finite program, at least as long as there’s a destination to fly to.

Steve Stitch: Station is our destination right now from a NASA perspective, so as long as space station is viable, these vehicles make sense to do this function from a US perspective.

Host: From the companies’ points of view, can they do anything else they want to with their space vehicle?

Steve Stitch: Yeah, they could take the vehicle and, as long as they meet NASA’s mission needs, they could take the vehicle and, down the road, propose a different mission, because of its commercial capability.

Host: It’s their spaceship.

Steve Stitch: It’s their spacecraft. It’s their mission control. It’s their launch vehicles, and in the case of the pads, SpaceX is leasing pad 39A from NASA, but they could propose a non-NASA mission and that’s something that we actually encourage them to do. If you think about, we’re really, we really have two purposes, it’s to support the space station program, and most of my time is spent working on these missions for space station, but it’s also to foster this commercial, this, you know, flying people into low-earth orbit on these vehicles, and so they could propose their own missions and do their own things with these vehicles, and that’s part of the idea of commercialization, you know.

Host: Right.

Steve Stitch: It’s the government is there as a bit of a anchor tenant, let’s just say, and then the companies can go propose to other entities other missions.

Host: A lot of people have made that argument, and I’ve heard it over the years, that it’s not like Boeing’s never flow into space before, or never wanted to, and I just, Boeing as the example, but they needed a reason to make the investment decision to do this or, in this case, to get some seed money from NASA to help fund the development of that. And that’s exactly, many people will say that’s exactly the role that a government ought to take, to help encourage businesses and then get out of their way.

Steve Stitch: Yeah. It’s a different model, a little bit, from what NASA’s done in the past.

Host: Oh yeah.

Steve Stitch: NASA was, you know, in charge of the mission, owned the vehicles, end to end. Now, it’s this, we are buying a service, and I would say we’re deeply involved in the missions from a perspective of checking to make sure that the requirements on these vehicles meet our safety requirements, and what I would call design and construction standards. The way you do a weld, or put wiring together, or whatever. We check, NASA checks all that to make sure we meet the safety specifications that we have outlined for the contract, and then, but then, you know, outside the NASA missions, it’s really up to the companies to take these vehicles that we’ve helped them develop and also, you know, look for other customers down the road. Now, right now, we’re kind of in the middle of getting the vehicles developed, so.

Host: It’s early.

Steve Stitch: It’s pretty early, in that regard, and obviously the demands that we’re putting on the companies to get these vehicles flying are pretty heavy, but down the road, certainly, it’s what we looked for these companies to do. And, if you kind of look back at many other industries, you think of the railroad industry, or early aviation industry, the government kind of seeded that work and then, you know, we let commercial companies take on, and now there’s just, if you think about air travel, and the number of commercial flights a day, it’s just staggering. Every time I go to an airport, I just, I’m amazed at the logistics of how planes come in and out, passengers are loaded, luggage is offloaded, and it really works, even though sometimes we complain when it doesn’t go well for us, it really works pretty well. Could you envision maybe not at the magnitude of the flights, but something like that in low?

Host: A spaceport.

Steve Stitch: Low-earth orbit someday? It absolutely could happen.

Host: And, in the meantime, in the process, if private companies are flying to the International Space Station, NASA can spend its time on other things.

Steve Stitch: Absolutely, absolutely. You know, if you look at how the launch vehicles were developed, you know, we’re utilizing the Atlas, Boeing has chose Atlas and that vehicle has been modified slightly for a commercial crew, but largely, it’s the vehicle that’s flying today on all the other Atlas missions. And then, SpaceX has the Falcon 9 flying today for other customers, and we’re leveraging that. So, if you sort of think about the way we’re utilizing those launch vehicles, and just building the spacecraft for, effectively, fairly cost-effective in the way we’re doing these missions. And so, it allows NASA to take the rest of its resources and then think about, what are they going to do with using Orion and the space launch system and the gateway and other missions there? And so, it’s a pretty exciting time in the agency. If you look at the number of vehicles being developed, it’s incredible. When we have, you know, Dragon crewed vehicle, we have the CST-100 vehicle, and we have Orion and the space launch system all being developed at the same time, you know, a lot of us, we’re used to the shuttle and space station, where we built the space station 20 years ago. Shuttle was built—

Host: Longer ago.

Steve Stitch: For me, a generation ago. Now, we’ve got all this development work. It’s pretty exciting for our engineers and for the country in general. I think many people don’t realize how, within aerospace, it’s kind of turning over that, how do you go build these complicated vehicles?

Host: It’s the first time that a new human-rated vehicle has been built in, as you say, in a generation.

Steve Stitch: In a generation. So, if you think about generations, you know, people that designed the space shuttle aren’t in the workforce today. These vehicles are now serving to sort of re-energize, I think, industry, and then our engineers today of how to build these vehicles. And then, if you think about long-term goals of the moon, or Mars, you know, we’re building a workforce and team and an industry that’s capable of doing those missions, as well, and I don’t think people see commercial crew doing that but, in some ways, we’re, because, you know.

Host: But, they may, once they start flying.

Steve Stitch: Right, right. We’re kind of re-energizing America industry to go do some of these more complicated missions later on, whether it be building a lander or a gateway habitat, or all these different missions.

Host: It’ll sure be interesting to watch it all happen, you know, coming up in the next year, we should see both vehicles fly a couple of times, and it’ll be cool to see what actually happens.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, I mean, we’re, you know, for SpaceX, we actually have a date on the range. For me, I’ve been in the commercial crew for three years, you know, when we first got that date with the range, it was kind of just a big, emotional thing for me, because we’ve been working so hard, and now, both emotionally from a, this is great, and then also, oh, wow, we really have a date on the range.

Host: It’s not theoretical anymore.

Steve Stitch: We’ve got to make sure—right, it’s not theoretical. I’ve got a date on the eastern range to fly one of these uncrewed demonstration missions, so, you know, when the crews are named, it becomes real, and then when you get to see hardware in Florida it becomes real, and then when you go, SpaceX goes and asks the range for a date, and you go look out there today on the eastern range schedule, and we have a date on the range, it really makes it a lot more real. And, you know, flying these uncrewed test flights are just as tough as flying with crew, and so we’re taking the time and energy to get it right, and review all the data. That’s really what we’re doing right now is reviewing the data for these, to get ready for these uncrewed test flights.

Host: It will be really cool to see it happen. Steve, thanks for bringing us up to speed.

Steve Stitch: Yeah, my pleasure. The neat thing about the work I get to do is, you know, there’s so many people here at the Johnson Space Center working so hard behind the scenes, not only here at JSC, but at the Marshall Space Flight Center, at the Kennedy Space Flight Center, and, you know, these people are working hard every day, and as we approach the holidays, they’re not spending time with their families sometimes to get this work done, and I couldn’t say enough about the team that we have that’s helping put all these vehicles together, not only on the government NASA side, but also at SpaceX and Boeing.

Host: It’s exciting to get ready to go fly.

Steve Stitch: It is, and I’m looking forward to it.

Host: Great. Steve, thanks very much.

Steve Stitch: Okay. Thank you.

[ Music ]

Host: Hey, there is more after the end of the show. Thanks for listening. Our conversation with Steve Stich, we learned a lot about the commercial crew program today, and you can find out more online. Go to nasa.gov/commercialcrew for the latest updates on the schedule for some of these missions that Steve talked about. Check out the schedule at nasa.gov/ntv, like in NASA television. You could also subscribe to our social media channels that will be posting updates as we get closer to the launch days for both the Boeing and the SpaceX vehicle. Check out the social media. The commercial crew is on Facebook @NASACommercialCrew, on Twitter @Commercial_Crew, and if you check both of those places, you can also use the hashtag #AskNASA on any of your favorite platforms, and to submit questions to us for the podcast, or ideas about other things we could do. While you’re online, you should also check out the other NASA podcast.

Go to nasa.gov/podcasts. You can find all of our episodes. You could also find the other podcasts that are done inside NASA, Gravity Assist, NASA in Silicon Valley, Rocket Ranch. They’re all pretty good, so give them a listen. This podcast was recorded on December 14th, 2018. Thanks to Gary Jordan, Alex Perryman, Norah Moran, Kelly Humphries, Kyle Herring, and Cindy McArthur. And, thanks again to Steve Stich for coming on the show. We’ll be back next week.