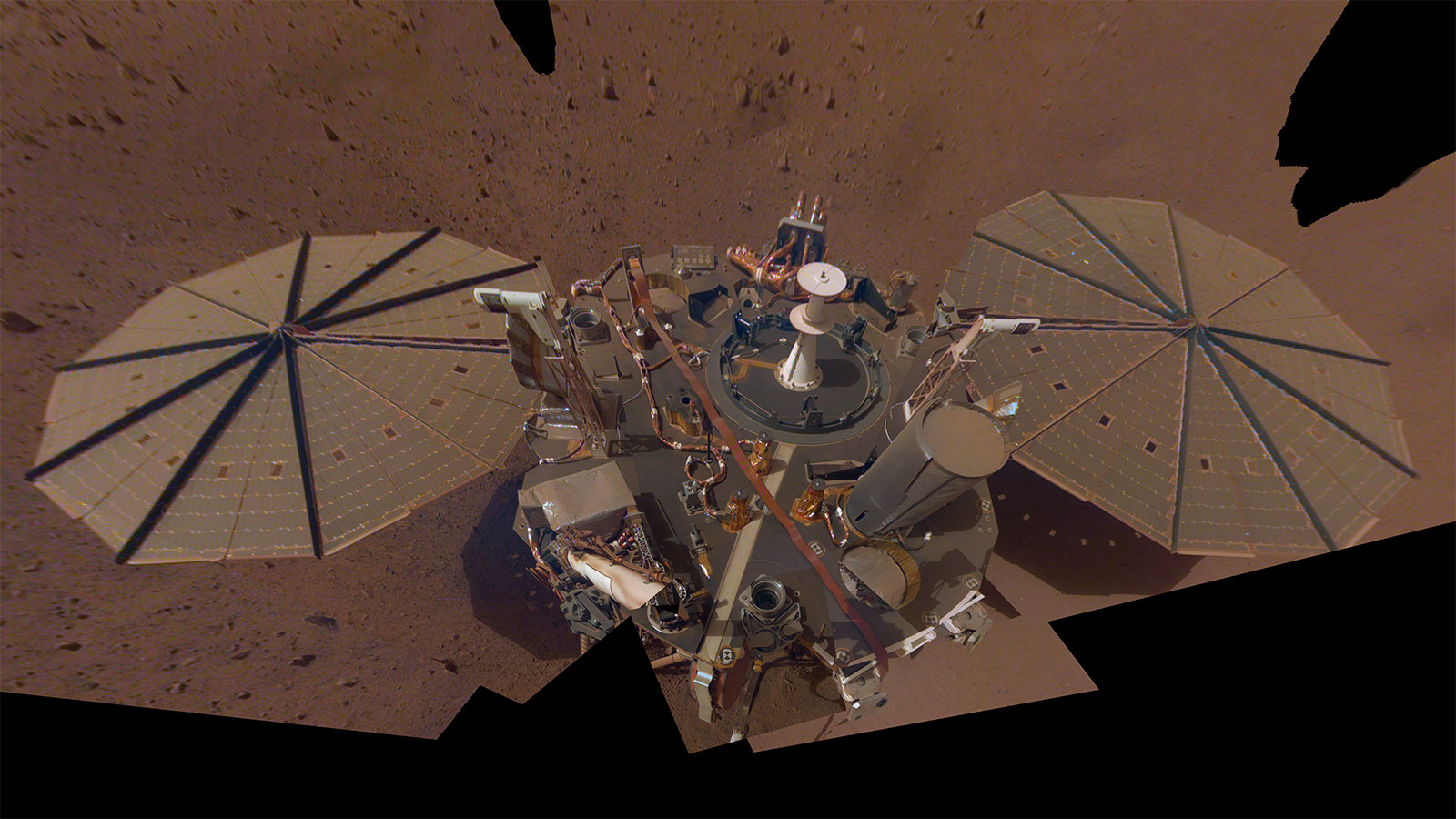

The lander cleared enough dust from one solar panel to keep its seismometer on through the summer, allowing scientists to study the three biggest quakes they’ve seen on Mars.

On Sept. 18, NASA’s InSight lander celebrated its 1,000th Martian day, or sol, by measuring one of the biggest, longest-lasting marsquakes the mission has ever detected. The temblor is estimated to be about a magnitude 4.2 and shook for nearly an hour-and-a-half.

This is the third major quake InSight has detected in a month: On Aug. 25, the mission’s seismometer detected two quakes of magnitudes 4.2 and 4.1. For comparison, a magnitude 4.2 quake has five times the energy of the mission’s previous record holder, a magnitude 3.7 quake detected in 2019.

The mission studies seismic waves to learn more about Mars’ interior. The waves change as they travel through a planet’s crust, mantle, and core, providing scientists a way to peer deep below the surface. What they learn can shed light on how all rocky worlds form, including Earth and its Moon.

The quakes might not have been detected at all had the mission not taken action earlier in the year, as Mars’ highly elliptical orbit took it farther from the Sun. Lower temperatures required the spacecraft to rely more on its heaters to keep warm; that, plus dust buildup on InSight’s solar panels, has reduced the lander’s power levels, requiring the mission to conserve energy by temporarily turning off certain instruments.

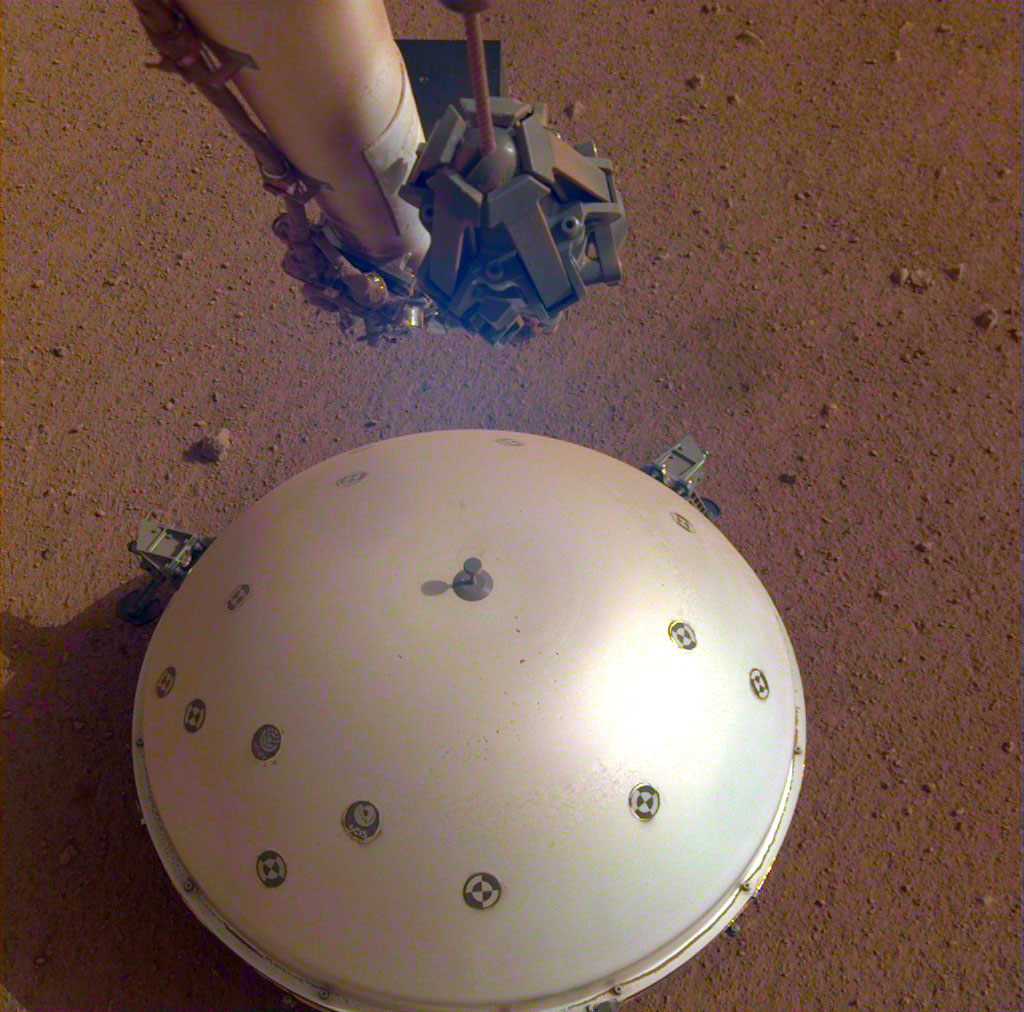

The team managed to keep the seismometer on by taking a counterintuitive approach: They used InSight’s robotic arm to trickle sand near one solar panel in the hopes that, as wind gusts carried it across the panel, the granules would sweep off some of the dust. The plan worked, and over several dust-clearing activities, the team saw power levels remain fairly steady. Now that Mars is approaching the Sun once again, power is starting to inch back up.

“If we hadn’t acted quickly earlier this year, we might have missed out on some great science,” said InSight’s principal investigator, Bruce Banerdt of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which leads the mission. “Even after more than two years, Mars seems to have given us something new with these two quakes, which have unique characteristics.”

Temblor Insights

While the Sept. 18 quake is still being studied, scientists already know more about the Aug. 25 quakes: The magnitude 4.2 event occurred about 5,280 miles (8,500 kilometers) from InSight – the most distant temblor the lander has detected so far.

Scientists are working to pinpoint the source and which direction the seismic waves traveled, but they know the shaking occurred too far to have originated where InSight has detected almost all of its previous large quakes: Cerberus Fossae, a region roughly 1,000 miles (1,609 kilometers) away where lava may have flowed within the last few million years. One especially intriguing possibility is Valles Marineris, the epically long canyon system that scars the Martian equator. The approximate center of that canyon system is 6,027 miles (9,700 kilometers) from InSight.

To the surprise of scientists, the Aug. 25 quakes were two different types, as well. The magnitude 4.2 quake was dominated by slow, low-frequency vibrations, while fast, high-frequency vibrations characterized the magnitude 4.1 quake. The magnitude 4.1 quake was also much closer to the lander – only about 575 miles (925 kilometers) away.

That’s good news for seismologists: Recording different quakes from a range of distances and with different kinds of seismic waves provides more information about a planet’s inner structure. This summer, the mission’s scientists used previous marsquake data to detail the depth and thickness of the planet’s crust and mantle, plus the size of its molten core.

Despite their differences, the two August quakes do have something in common other than being big: Both occurred during the day, the windiest – and, to a seismometer, noisiest – time on Mars. InSight’s seismometer usually finds marsquakes at night, when the planet cools off and winds are low. But the signals from these quakes were large enough to rise above any noise caused by wind.

Looking ahead, the mission’s team is considering whether to perform more dust cleanings after Mars solar conjunction, when Earth and Mars are on opposite sides of the Sun. Because the Sun’s radiation can affect radio signals, interfering with communications, the team will stop issuing commands to the lander on Sept. 29, though the seismometer will continue to listen for quakes throughout conjunction.

More About the Mission

JPL manages InSight for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA’s Discovery Program, managed by the agency’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built the InSight spacecraft, including its cruise stage and lander, and supports spacecraft operations for the mission.

A number of European partners, including France’s Centre National d‘Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES provided the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument to NASA, with the principal investigator at IPGP (Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris). Significant contributions for SEIS came from IPGP; the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany; the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) in Switzerland; Imperial College London and Oxford University in the United Kingdom; and JPL. DLR provided the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument, with significant contributions from the Space Research Center (CBK) of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Astronika in Poland. Spain’s Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) supplied the temperature and wind sensors.

Andrew Good

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-2433

andrew.c.good@jpl.nasa.gov

Karen Fox / Alana Johnson

NASA Headquarters, Washington

301-286-6284 / 202-358-1501

karen.c.fox@nasa.gov / alana.r.johnson@nasa.gov

2021-198