By Linda Herridge

NASA’s John F. Kennedy Space Center

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has been in service for 30 years this month. Though only projected to be in service for about 10 years when it launched aboard space shuttle Discovery’s STS-31 mission on April 24, 1990, from Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the unique telescope is still a technological marvel even today.

The telescope was named in honor of astronomer Edwin Hubble and his work beginning in the 1920s to discover galaxies beyond our own.

Orbiting about 340 miles above the Earth and traveling at around 17,000 miles per hour (5 miles per second), Hubble continues to reach back into time to capture stunning images of the universe and our own Milky Way galaxy with its 100-inch-wide primary mirror. The telescope is credited with discovering many distant galaxies, confirming the supermassive black holes that exist in galactic centers, and discovering birthplaces of stars, relaying images almost too mind-boggling to comprehend.

Hubble’s first image was captured on May 20, 1990 of Star cluster NGC 3532. In its lifetime, the extremely productive telescope has taken over a million observations.

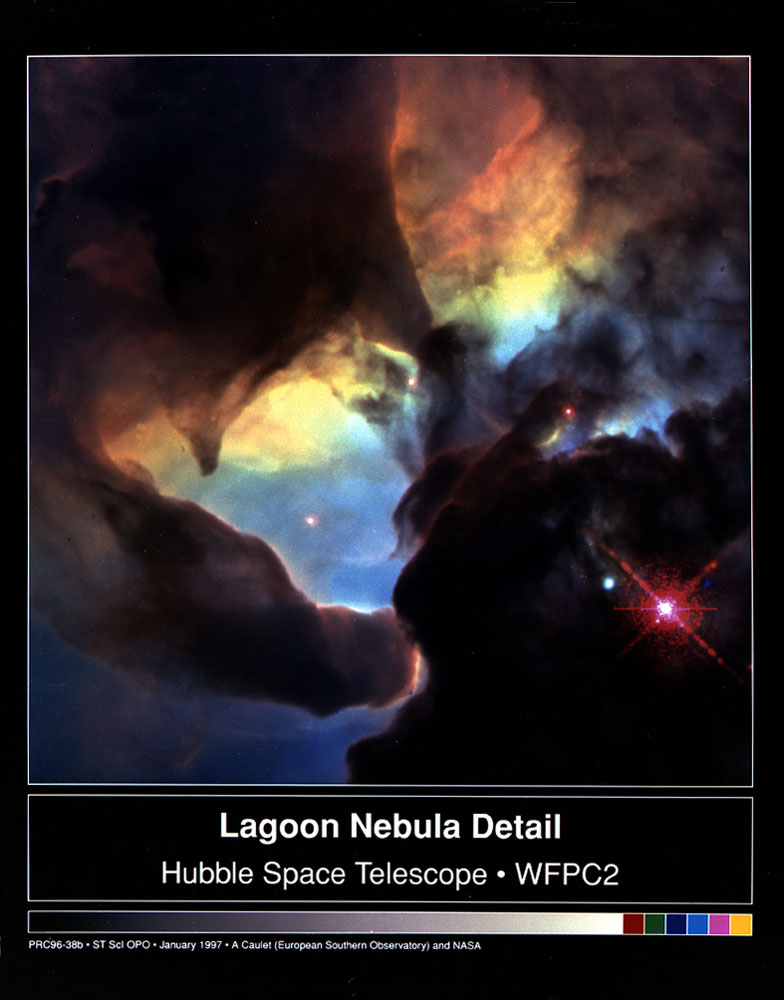

In 2018, Hubble imaged a young star 200,000 times brighter than our Sun at the center of the Lagoon Nebula. The star is blasting powerful ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds, carving shapes out of the surrounding gas and dust.

Hubble has provided the best evidence yet for an underground saltwater ocean on Ganymede, Jupiter’s largest moon. The under-ice ocean may contain more water than all of the water on Earth’s surface. About nine years ago, Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 found what was thought at the time to be the most distant object ever seen in the universe. The object’s light traveled 13.2 billion years to reach Hubble, roughly 150 million years longer than the previous record holder. The very dim and tiny object is a compact galaxy of blue stars that existed as early as 480 million years after the Big Bang.

Hubble’s journey to space began when it arrived at Kennedy in October 1989 on a U.S. Air Force C-5A transport jet from the Lockheed Martin facility in California. The huge telescope was transported to the Vertical Processing Facility for prelaunch preparations. The center’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility also was used for offline processing of Hubble science instruments.

Even before launch, there were some challenges. Hubble was delivered to the pad late in the processing timeline (to minimize its time at the pad) and prepared for installation in the payload bay using the pad’s payload changeout room (PCR). But hundreds of midges, a kind of small fly, had hatched and settled on the payload bay doors, resulting in an unknown number of them getting into the PCR. The doors were quickly closed and an environmental team was called in to devise a system to remove the flies. When the PCR was clear, it took eight hours to install and secure the nearly 44-foot-long Hubble in Discovery’s payload bay for the trip to space. Precise measurements of the bay and the telescope had been taken in advance to ensure the clearances.

On the original launch day, April 10, 1990, pilot Charlie Bolden flipped the switches on the shuttle’s auxiliary power units (APU) and the launch team realized something was wrong. The flight was delayed two weeks while the faulty APU was changed out.

In a process that had never been planned for, the payload team removed Hubble’s batteries inside the payload bay and took them to the Space Shuttle Main Engine Facility in the Vehicle Assembly Building to keep them charged. A few days before launch, the batteries were reinstalled.

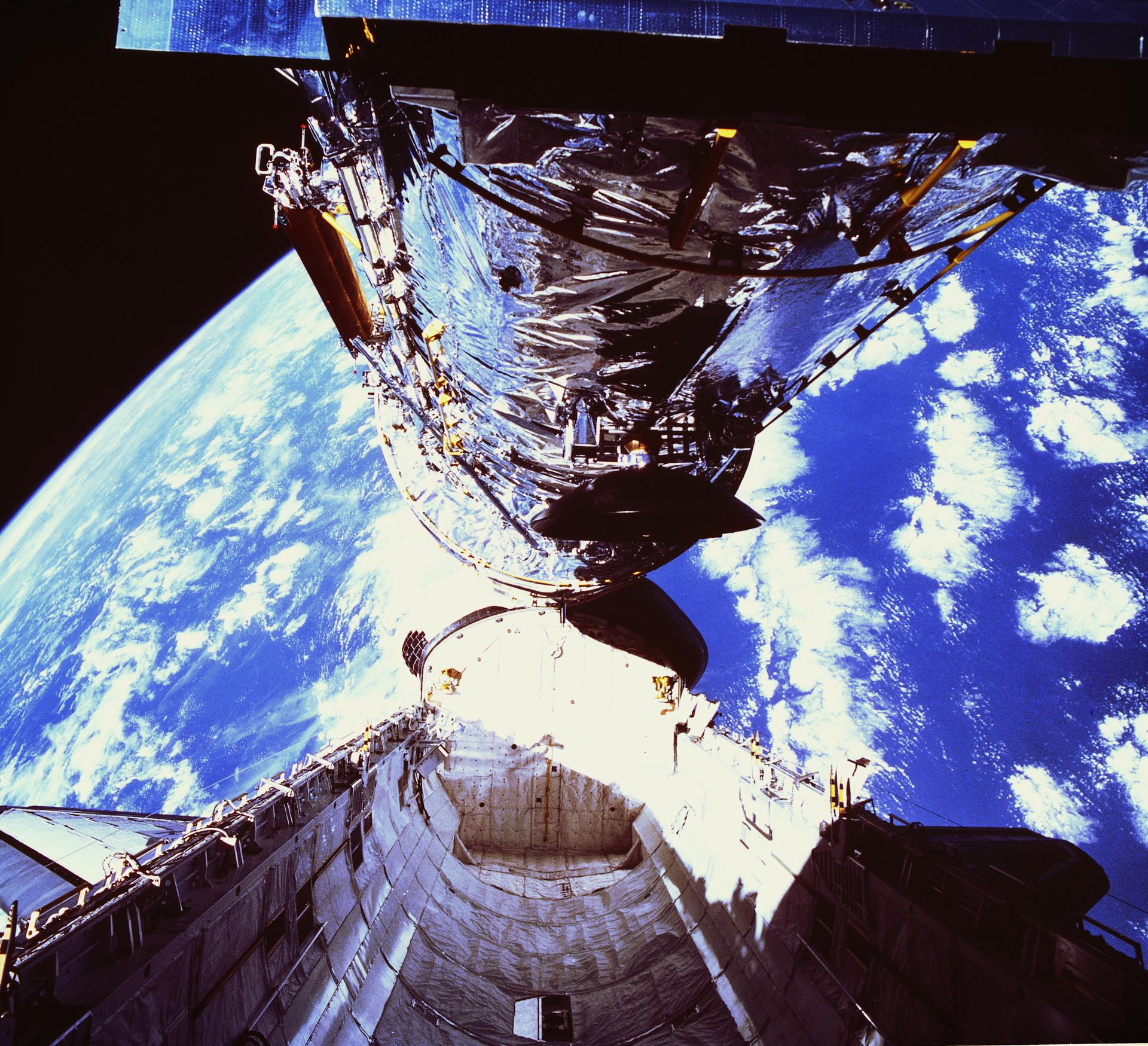

The telescope’s mission began the day after it arrived in orbit inside Discovery’s payload bay. Using the shuttle’s robotic arms, the telescope was deployed into orbit by crewmembers on April 25.

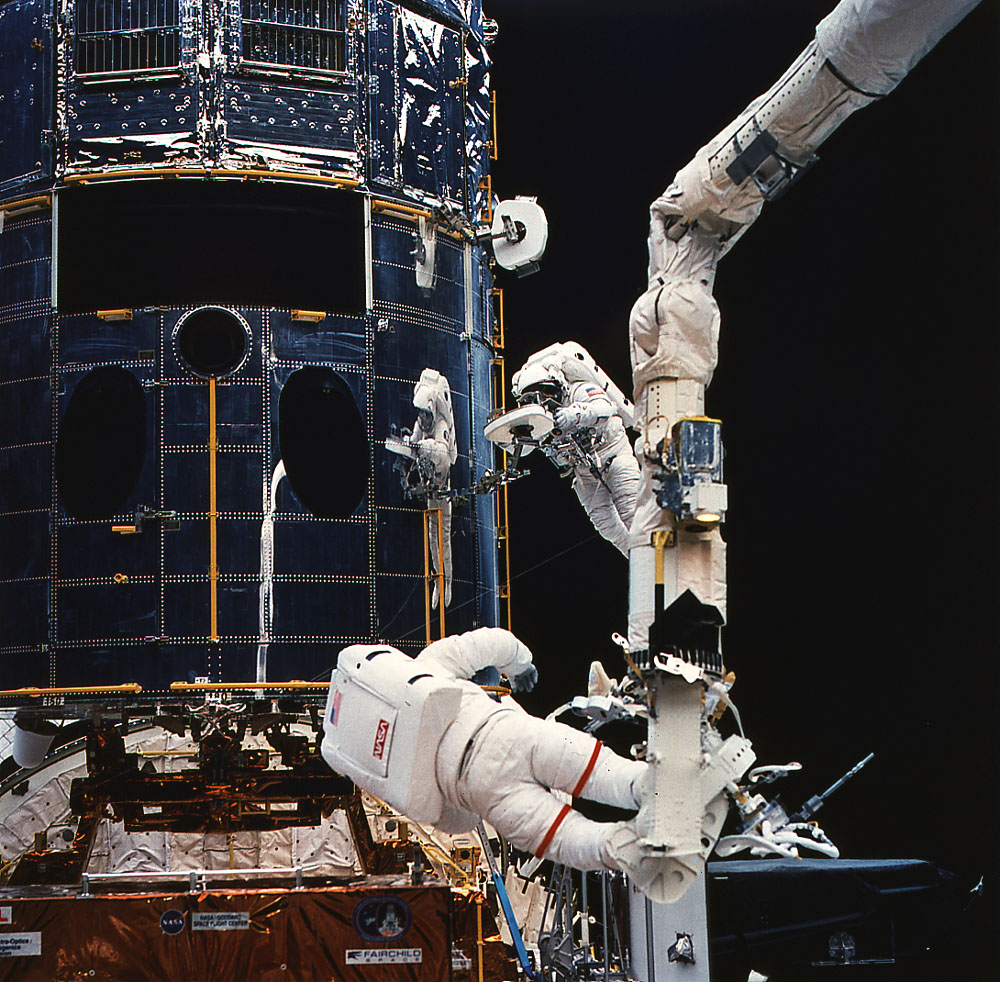

Hubble was built serviceable and modular, so that science instruments and components could be changed out and problems fixed.

During its life in space, there have been five Hubble Servicing Missions to upgrade the telescope: Servicing Mission 1 (STS-61), December 1993; Servicing Mission 2 (STS-82), February 1997; Servicing Mission 3A (STS-103), December 1999; Servicing Mission 3B (STS-109), February 2002; and Servicing Mission 4 (STS-125), May 2009.

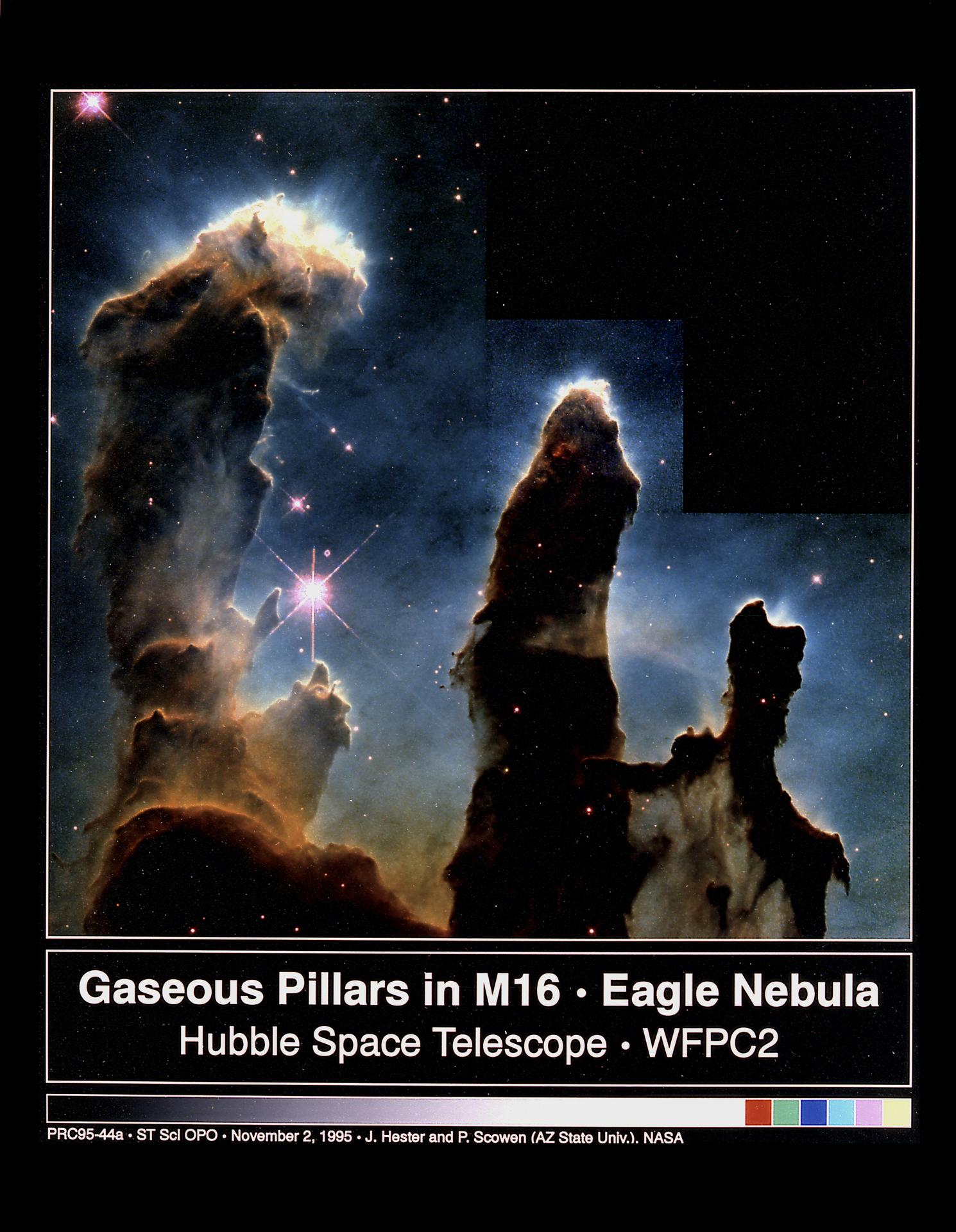

The first servicing mission in 1993 was to correct a spherical aberration that was creating blurry images in the initial images from Hubble. After the fix, the telescope’s camera provided one of its most famous and recognizable picture, called the Eagle Nebula. Astronauts returned four more times to upgrade or replace several of the telescope’s sensitive instruments. Each servicing mission increased the scientific capabilities of the observatory.

On the second servicing mission, the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) was installed on Hubble. Using its imaging spectrograph, STIS confirmed the existence of supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies.

Significant technical capabilities were advanced through the course of the servicing program. For example, great improvements were made in photolithography from Hubble’s instrument called COSTAR, which had within it corrective optics. From this instrument, a key process for improving transistor density on a chip while making microchips was developed. The addition of more transistors increases the density of the chip, which increases computational ability and memory. Other technology spinoffs from Hubble include several in the medical field, computer technology, sports and Earth science.

Now in its 30th year, the Hubble Space Telescope continues to open our eyes to the wonders in and beyond our own galaxy and has contributed to improving life on our own planet.