In April 1980, preparations to launch the first Space Shuttle continued. NASA hoped to launch STS-1, the first flight of Columbia, by November 1980 although even senior managers agreed that the date might slip into early 1981. The Space Shuttle constituted the most complex human space flight system ever designed and unexpected delays could not be avoided. Engineers at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) continued testing the flight hardware that had arrived there over the previous months. The prime crew of John W. Young and Robert L. Crippen, along with their backups Richard H. Truly and Joe H. Engle, trained on the various aspects of their upcoming mission. In Mission Control at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, flight controllers carried out simulations to prepare their teams for the first flight of the reusable space vehicle.

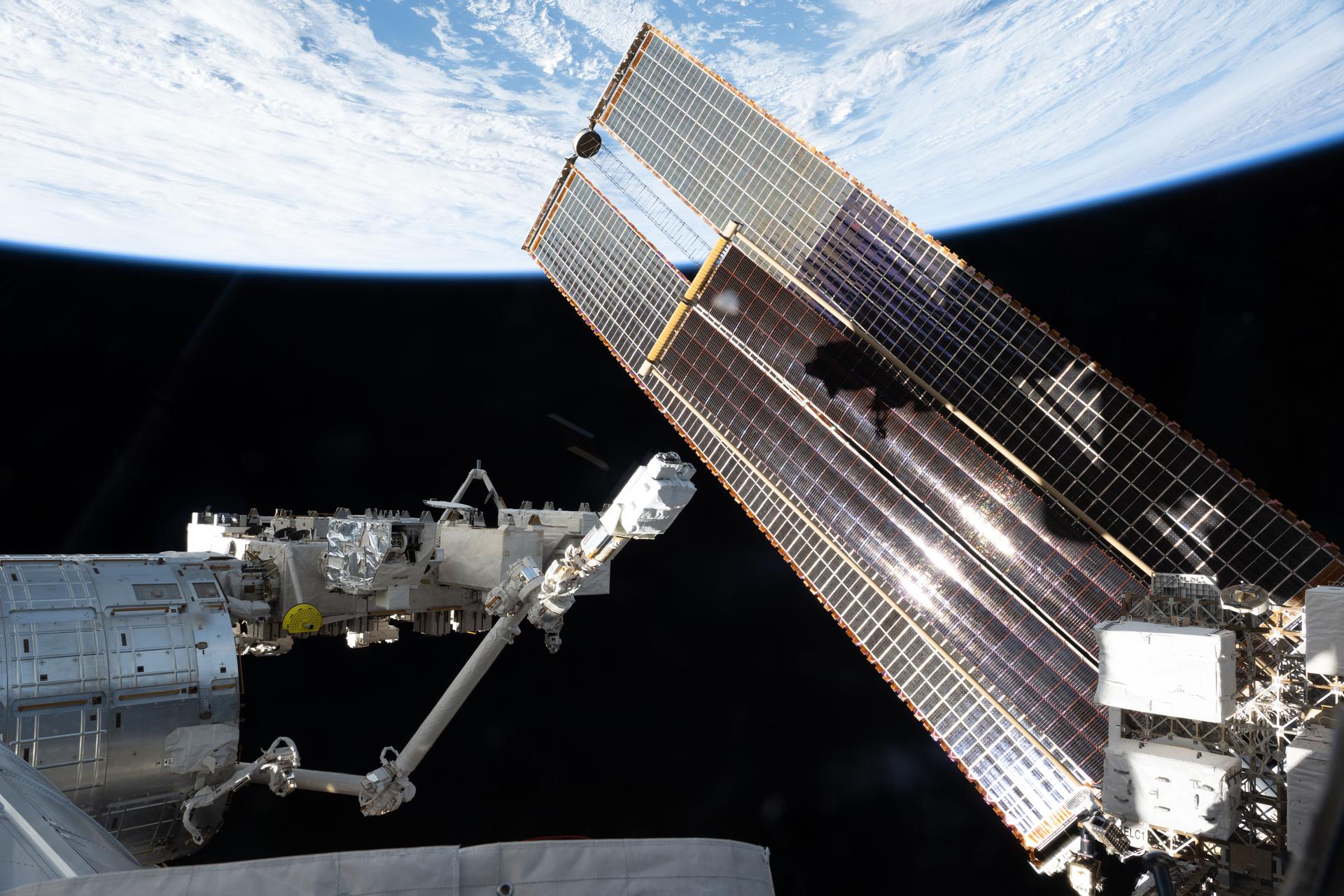

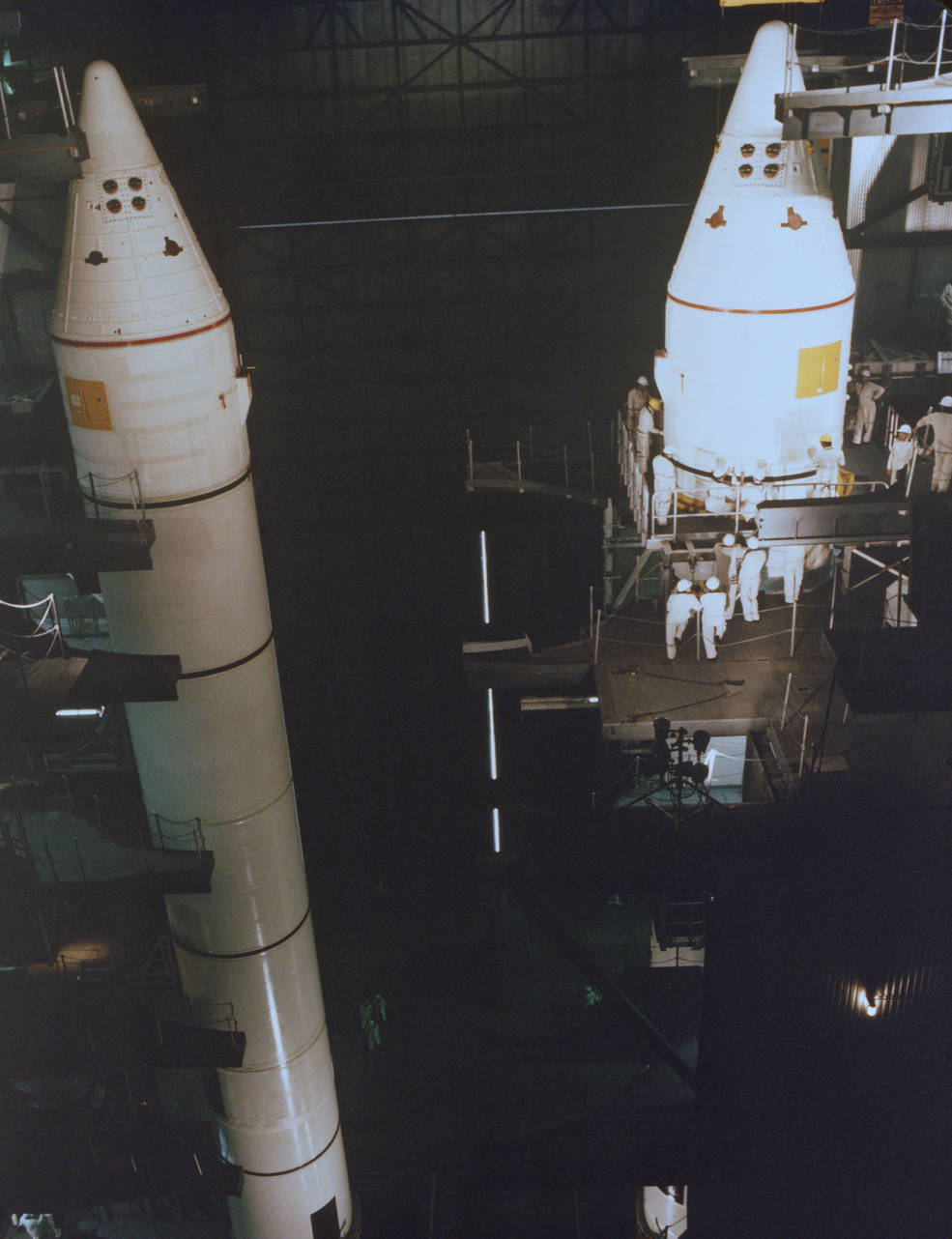

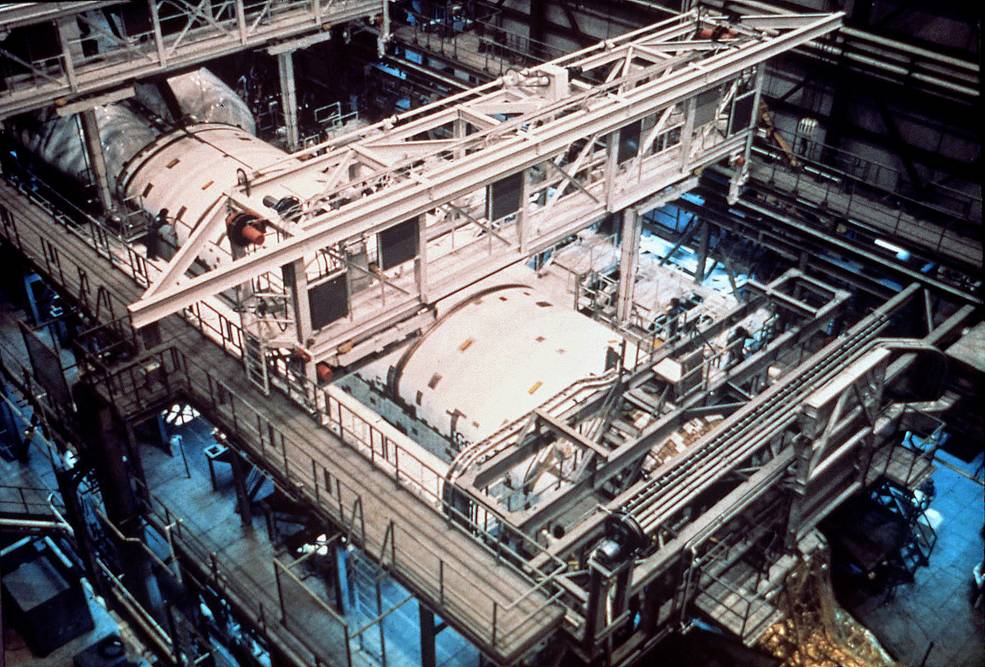

Left: The two SRBs for STS-1 stacked on the MLP in the VAB. Middle: The ET for STS-1 in a test cell in the VAB. Right: Space Shuttle Orbiter Columbia undergoing testing in the OPF.

All the major components for the first flight of the Space Shuttle had arrived at KSC. Segments for the two Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) began arriving from their manufacturer, the Thiokol Corporation in Brigham City, Utah, in 1979 and in January 1980 workers in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) stacked them on the Mobile Launch Platform (MLP). The External Tank (ET) for STS-1 arrived in July 1979 by barge from the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, Louisiana, where prime contractor Martin Marietta assembled it. Workers towed it into the VAB for testing and mating to the SRBs in the coming months. The Orbiter Columbia arrived in March 1979 and engineers continued testing and performing other work in the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF). Significant work remained on Columbia, including its three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) and the main pacing item for the planned launch, the heat-resistant tiles that comprised its heat shield, or Thermal Protection System (TPS). Hundreds of technicians continued to apply the TPS tiles to Columbia and testing their adhesive strength so that by April 1980 only 7,000 of the total of the total 31,000 tiles that covered the Orbiter remained to be applied and pull tested.

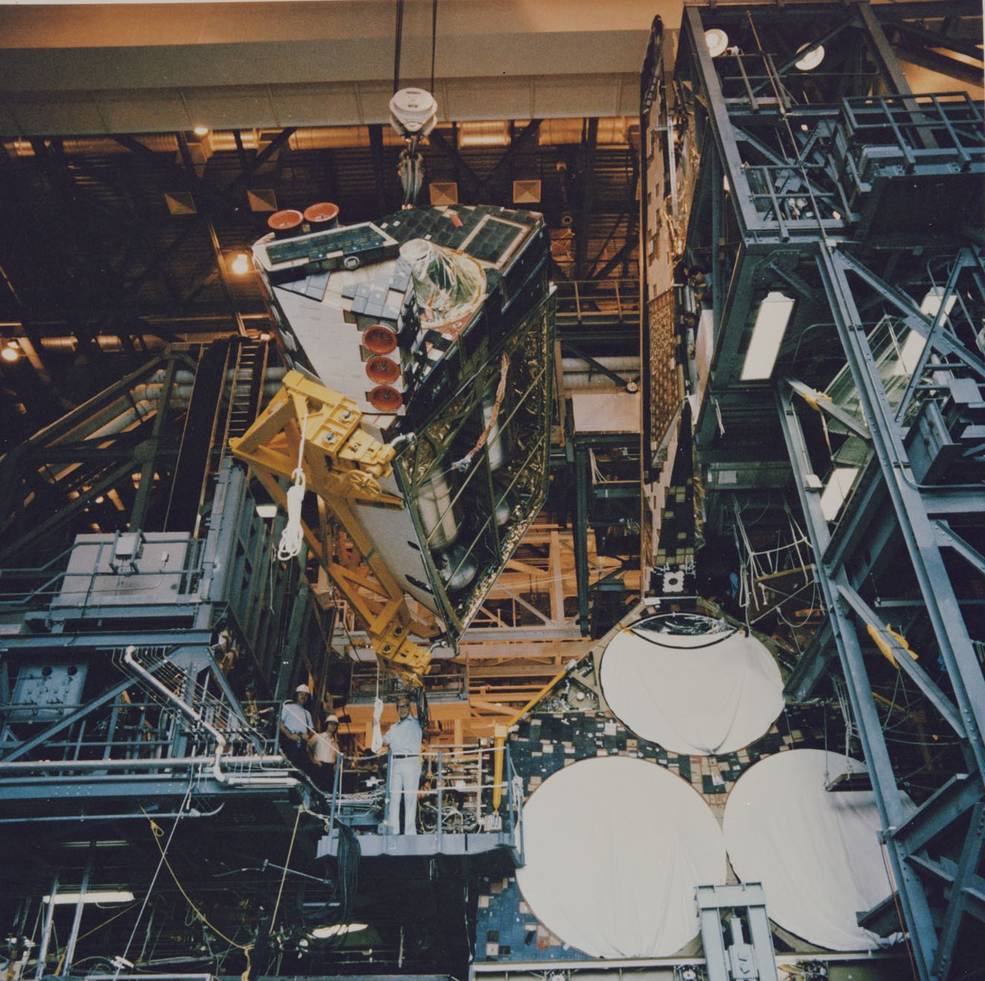

Left: Technician at KSC applying a TPS tile to Columbia in the OPF. Middle: View of Columbia’s underside showing areas of tiles yet to be installed. Right: STS-1 prime crew of Crippen (left) and Young in the OPF during an award presentation to the tile workers.

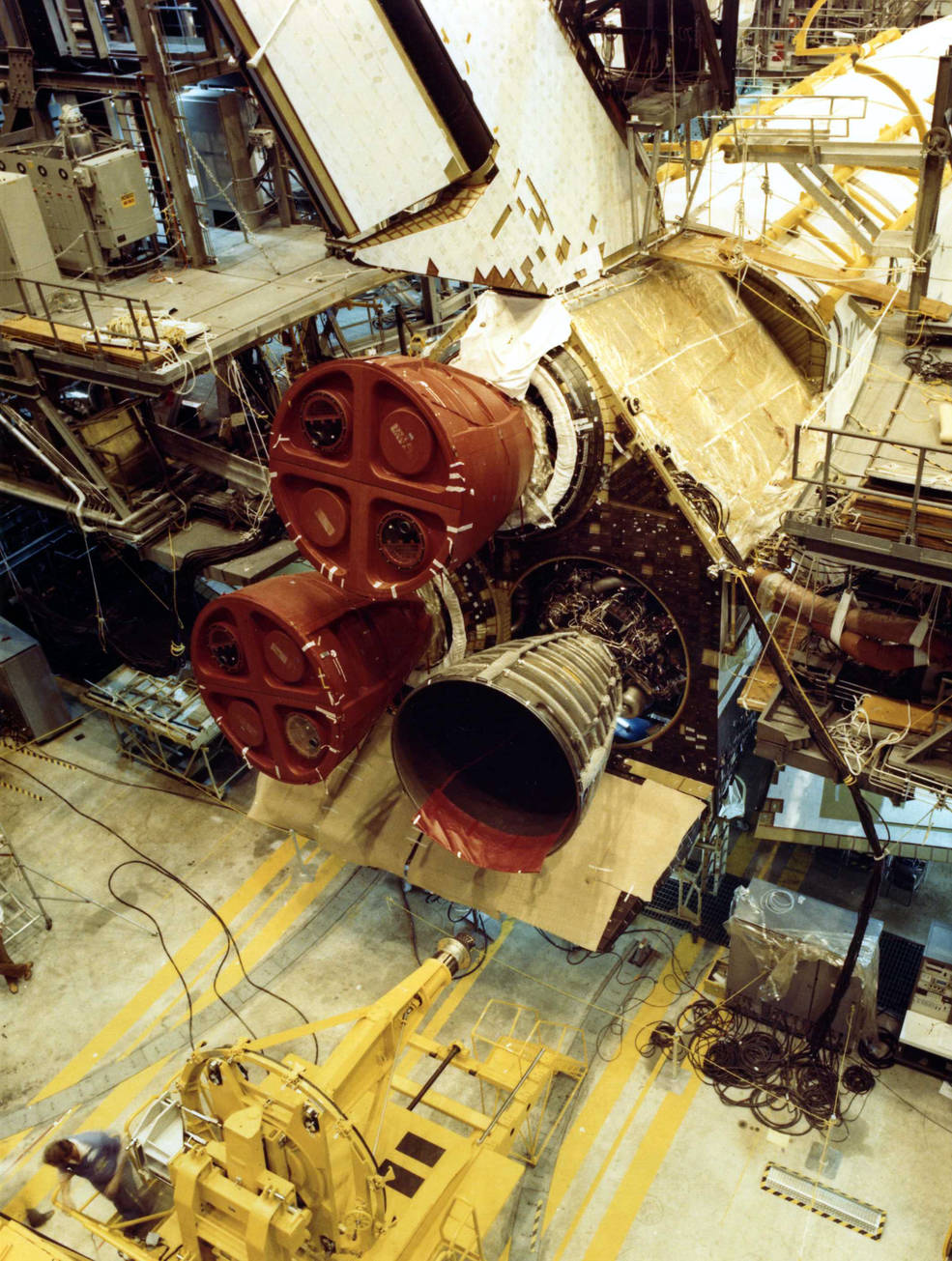

The SSMEs were the most sophisticated and efficient rocket engines built up to that time. The three engines mounted at the rear of the Orbiter helped to lift the Space Shuttle off the pad and eventually place it into orbit. Burning liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen stored in the ET, each engine generated 375,000 pounds of thrust at liftoff and 470,000 pounds in vacuum. The three SSMEs assigned to Columbia’s first mission had passed certification and workers had installed them on the Orbiter in 1979, but unrelated testing revealed modifications were necessary. Workers removed the engines from Columbia and sent them to the National Space Transportation Laboratory (NSTL), now the John C. Stennis Space Center, in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, for additional full-duration testing in June 1980. Workers at NSTL continued to test other SSMEs in a lengthy certification process of testing single engines and clusters of three engines using the Main Propulsion Test Article (MPTA) consisting of an aft Shuttle fuselage and an engine thrust structure outfitted to simulate the Shuttle’s propulsion systems. The MPTA was mated to an ET in the test stand for the engine firings. Two full-duration tests on March 20 and 31 included gimballing the engines and increasing the thrust to 109%, respectively. Another cluster test on April 16 was automatically shut down after five seconds due to component overheating and was later repeated. The Orbiter Maneuvering System (OMS) engines used by the Shuttle to make orbital corrections including the maneuver for reentry were located in pods adjacent to the tail of the vehicle. Workers installed the two OMS pods on Columbia in March 1980.

Left: SSMEs being installed on Columbia in the OPF in 1979. Middle: Single SSME

test at NSTL. Right: Left OMS pod being installed on Columbia – note the SSMEs have been removed.

The SRBs provided 2.8 million pounds of thrust at ignition to lift the Shuttle stack off the launch pad, aided by the three SSMEs. Once they exhausted their fuel about two minutes after liftoff, the SRBs made parachute assisted splashdowns in the Atlantic Ocean. Crews recovered them at sea and towed them back to port for refurbishment and eventual reuse. To rehearse these activities, sailors used the Ocean Test Fixture (OTF), a high fidelity mockup of an SRB. The Bering Sea delivered the OTF to Port Canaveral, Florida, near KSC from Jacksonville, Florida, in early March. Full scale recovery rehearsals took place in April and May.

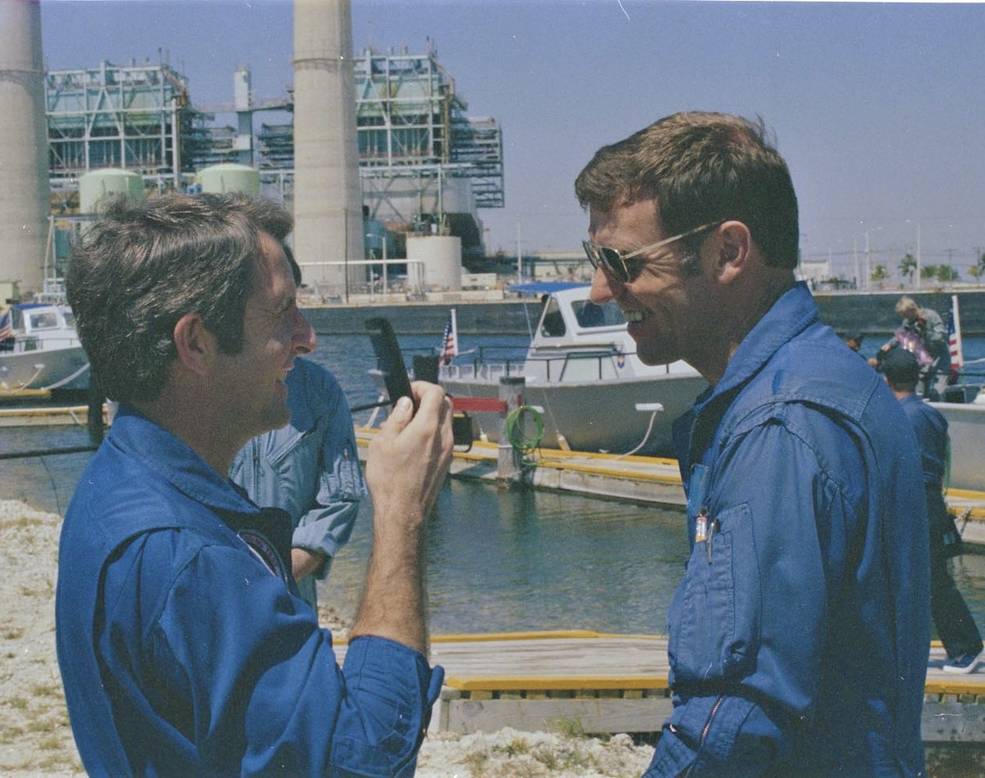

Left: STS-1 backup crewmembers Truly (left) and Engle prepare for water survival training. Middle: An STS-1 crewmembers parasailing during water survival training. Right: STS-1 crewmember in lift raft during water survival training.

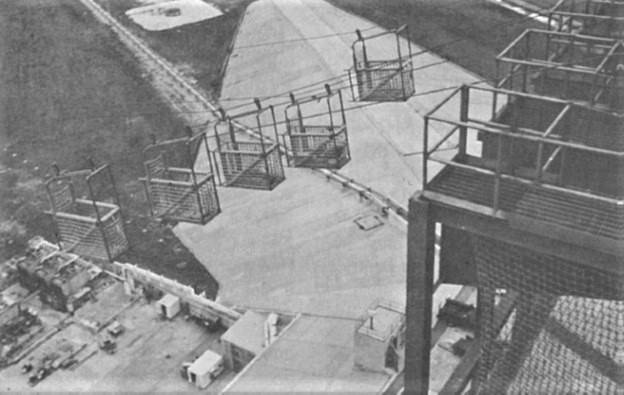

In case of an emergency during the final minutes of a launch countdown, astronauts and support personnel at the Orbiter Access Arm level of the Fixed Service Structure of Launch Pad 39A would make use of a slide wire system to make their escape. They would climb aboard five flat-bottomed baskets, each of which could hold 2-3 people, and then slide down the length of the 1,200-foot cable to ground level where they could seek shelter. During validation tests conducted in March without personnel actually riding down in the baskets, the average time from exiting the Orbiter to arriving on the ground was 19 seconds.

Left: Two test subjects simulate a launch pad emergency requiring use of the

slide wire baskets. Middle: The five rescue baskets in their parked positions.

Right: The rescue five baskets have been released and are on their way down

their respective wires.

For its first four orbital test flights, Space Shuttle Columbia carried ejection seats affording the two pilots the opportunity to escape from a spacecraft emergency up to an altitude of 80,000 feet. The astronauts would then parachute into the Atlantic Ocean and board personal life rafts to await recovery. To practice for that contingency, Young, Crippen, Engle and Truly attended an abbreviated water survival training course at the USAF Water Survival School at Homestead Air Force Base in Florida on April 16. During the training exercise the astronauts wore high-altitude pressure suits similar to those they wore during the actual mission.

Left: STS-1 backup crewmembers Truly (left) and Engle prepare for water survival training. Middle: An STS-1 crewmembers parasailing during water survival training. Right: STS-1 crewmember in lift raft during water survival training.

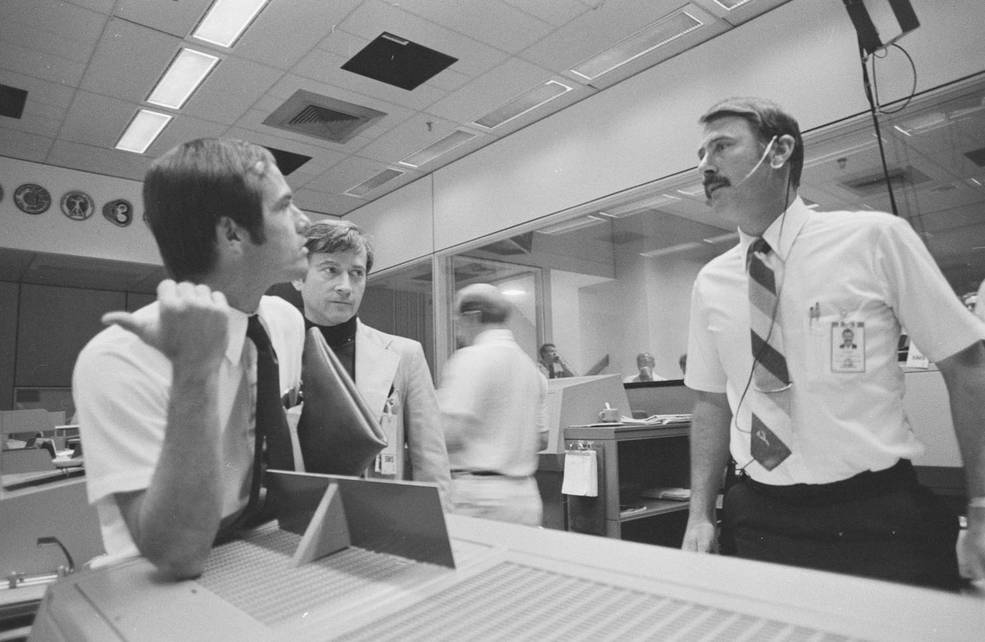

Between April 22 and 24, flight controllers, trainers and astronauts completed a 54-hour full-duration simulation of the STS-1 mission in Mission Control at JSC. Led by Flight Directors Neil B. Hutchinson, Charles R. Lewis and Donald R. Puddy, teams of controllers monitored Orbiter systems from a simulated launch to a simulated landing and all mission phases in between. Nearly 500 people participated in the test, supporting STS-1 backup crewmembers Engle and Truly as they “flew” the orbiter Columbia in the Shuttle Mission Simulator. Trainers introduced anomalies into the simulation to exercise the flight control teams, including the Capsule Communicators, or Capcoms, the astronauts who talk directly to the flight crews. Astronauts Joseph P. Allen, Daniel C. Brandenstein, Frederick H. “Rick” Hauck and Terry J. Hart participated as Capcoms during the simulation. Flight Director Hutchinson said of the team’s response to the simulated anomalies, “If we can overcome similar problems in an actual flight, we could definitely call that flight successful.” Mission Control held several more full-duration simulations before the actual flight of STS-1 in April 1981.

Left: Flight Directors Puddy and Lewis monitor events during the first STS-1 54-hour full-duration mission simulation. Right: STS-1 prime crew (left to right) Crippen and Young confer with Flight Director Puddy during the STS-1 54-hour full-duration mission simulation.

Left: Flight Director Hutchinson during the 54-hour simulation. Right: Capcoms Allen (in blue shirt) and Hauck (in tan shirt) confer with STS-1 Commander Young during the 54-hour simulation as Capcom Hart (far right) sits nearby.

To be continued…