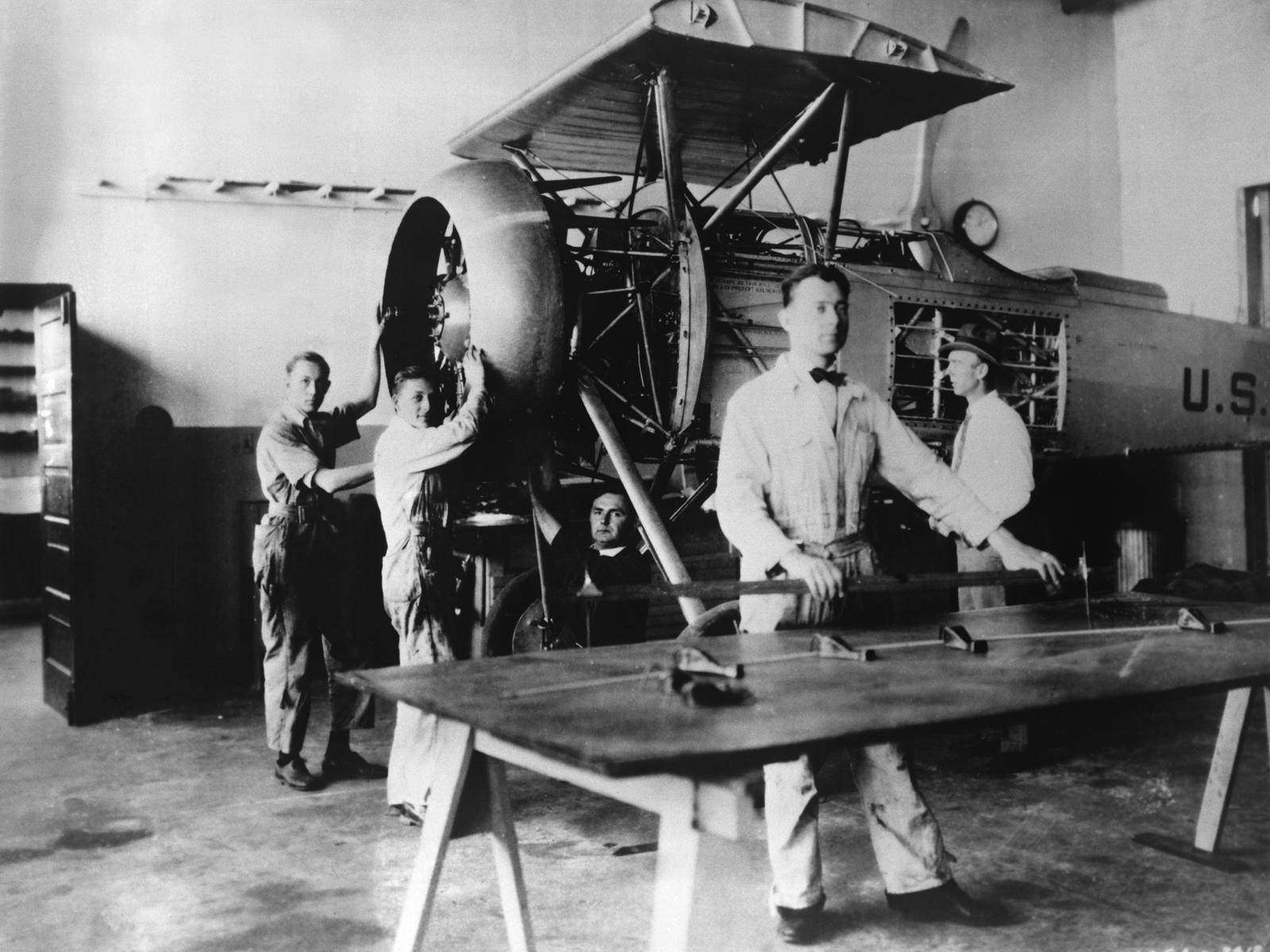

Ninety-five years ago a committee of 12 volunteers with a budget of $5,000 embarked on a mission to change the face of U.S. aviation, and in doing so established a legacy of innovative aeronautical research that continues at NASA today.

Established by Congress on March 3, 1915, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, or the NACA, convened its first meeting a few weeks later with marching orders to “supervise and direct the scientific study of the problems of flight, with a view to their practical solutions.”

By the time the NACA morphed into NASA in 1958, the nation’s best and brightest aeronautical engineers had established world-class laboratories, steadfastly pioneered the unknown of flight and won five Collier Trophies, the greatest honor in aviation.

“In fact, there are no production airplanes flying anywhere in the world today that do not rely on some technology derived from NACA research,” said Jaiwon Shin, associate administrator for NASA’s Aeronautics Research Mission Directorate in Washington.

When the NACA was formed, a dozen years had passed since the Wright Brothers made their historic flight at Kitty Hawk, and Americans had yet to embrace the airplane. We were more impressed in 1915 by Henry Ford producing his one millionth automobile.

Aeronautical researchers in Europe, however, were more aggressive in developing the airplane and by the time World War I began in 1914 the United States was behind the world in aviation. Forming the NACA was a direct response to that situation.

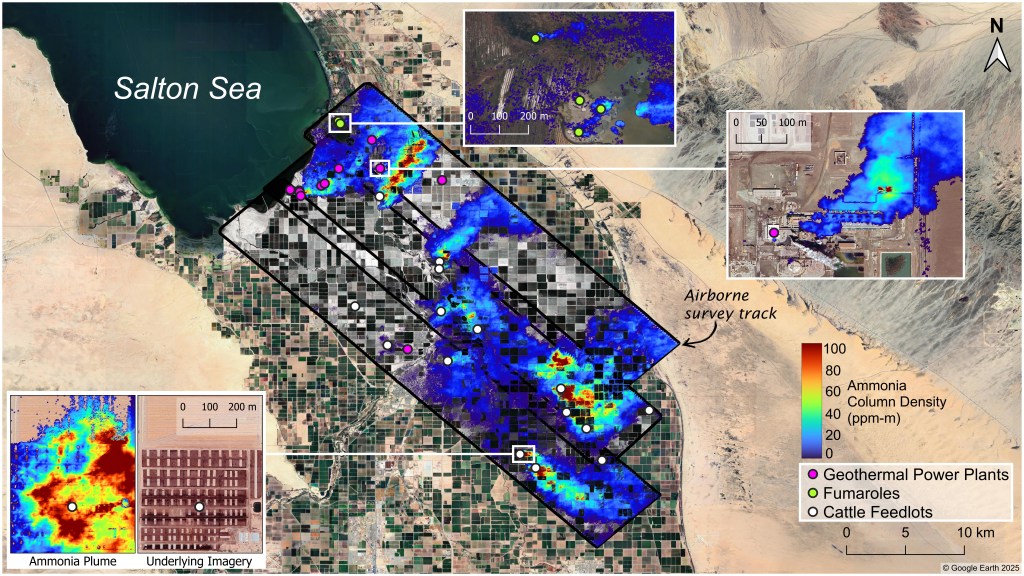

Laboratories in Virginia, California and Ohio were constructed and soon became the centers of aviation research tasked by the committee. It was at these places known as Langley, Ames, Dryden and Lewis that the NACA made some of the most important contributions to aviation. They included development of a:

- Cowling to improve the cooling of a radial engine, which also reduced drag on the aircraft.

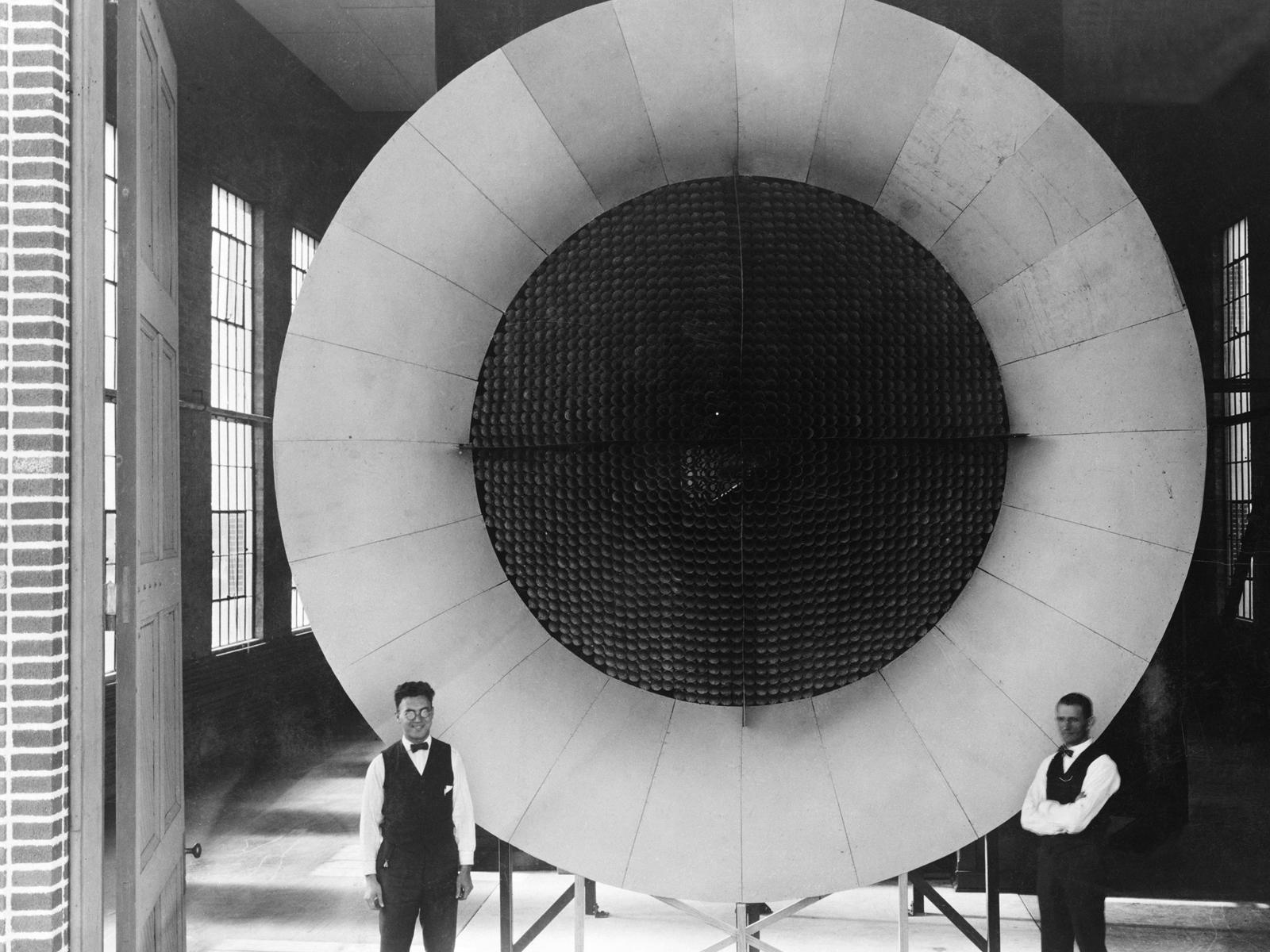

- Wind tunnel that can simulate air density at different altitudes, which engineers used to design and test dozens of wing cross-section shapes.

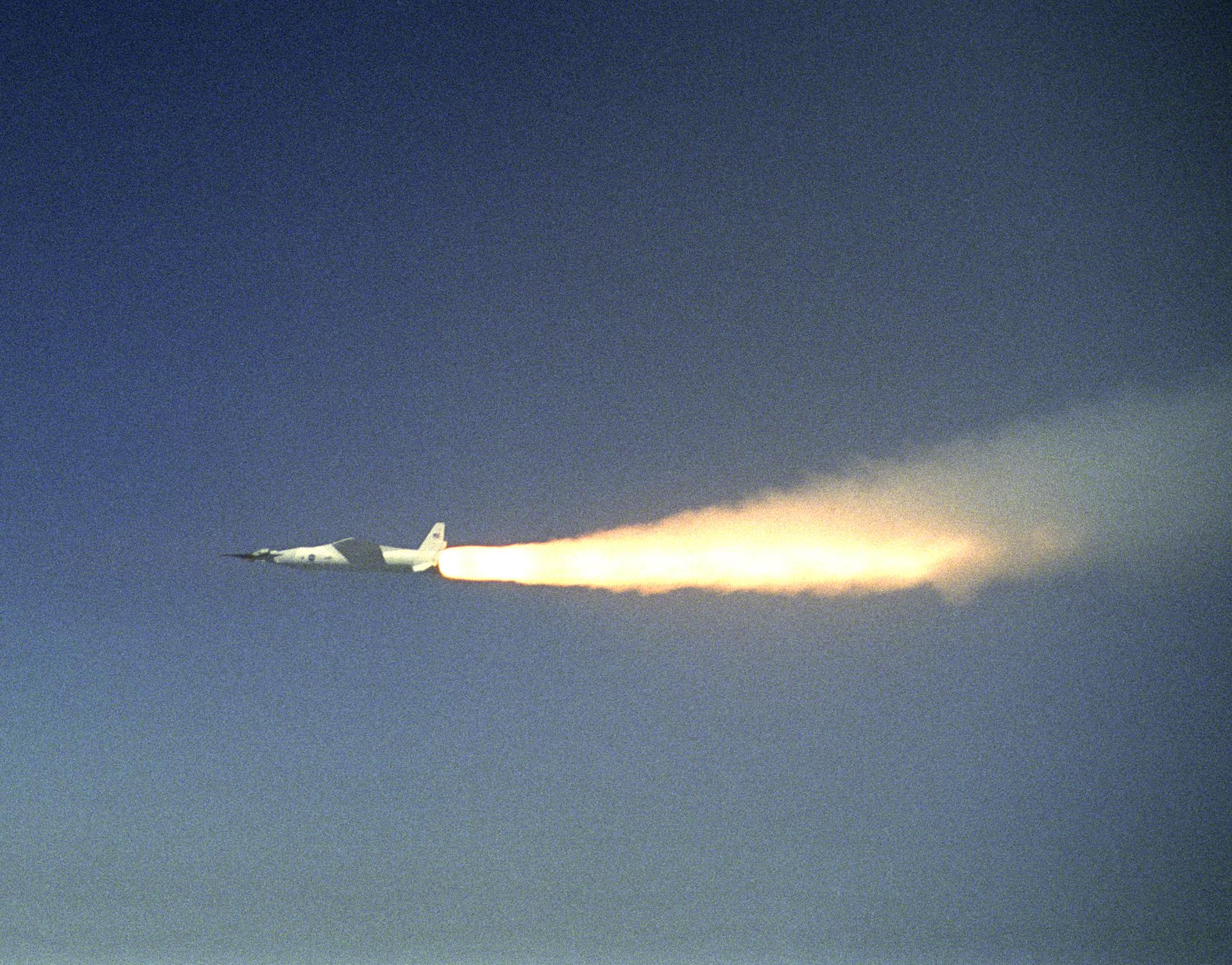

- Wind tunnel with slots in its wall that allowed researchers to take measurements of aerodynamic forces at near supersonic speeds.

- Design principle involving the shape of an aircraft’s wing in relation to the rest of the airplane to reduce drag and allow supersonic flight.

In addition to the technical discoveries, one of the greatest contributions of the NACA was its insistence on producing and widely distributing its reports, memoranda and notes, which allowed the rest of the aviation community to take full advantage of the research results.

All of these contributions continue to be in use today and further opened the doors to enhancement as research methods and technology improved, namely going from the slide rule to the desktop computer.

The NACA ceased to exist in its own right on Sept. 30, 1958—becoming the foundation for NASA, which opened for business the next day.

By that time, the jet age had arrived and NACA researchers already were studying problems regarding spaceflight, including how to return an object in space through Earth’s atmosphere.

Overnight, NASA inherited a generation of experience in managing government research projects, operating the finest laboratories and wind tunnels, and training the brightest aeronautical engineers to conduct cutting-edge research.

The rapid rise of the space program that followed, and NASA’s ability to successfully answer President Kennedy’s challenge to the moon would not have been possible without that firm foundation laid by the NACA.

The NACA’s spirit and innovative approach to research continues today, said Richard P. Hallion, a respected aviation historian and author of the NASA publication On the Frontier: Flight Research at Dryden, 1946–1981:

The fact that we had an NACA serves today as an inspiration to our modern aeronautics researchers, many of whom are working in the same facilities created in the heyday of the NACA. They remain committed to the same quest for excellence as the original trailblazers.

Richard P. Hallion

Aviation Historian and Author

Engines and Innovation: Lewis Laboratory and American Propulsion Technology →

NACA Technical Reports and Memoranda (keyword “NACA”) →

On the Frontier: Flight Research at Dryden, 1946-1981 →

Orders of Magnitude: A History of the NACA and NASA, 1915-1990 →

Searching the Horizon: A History of Ames Research Center, 1940-1976 →