Astronauts traveling in space are faced with both common terrestrial and unique spaceflight-induced health risks. The primary focus of NASA medical operations is to prevent the occurrence of inflight medical events, but to be prepared to provide robust clinical management when they do occur. Inflight medical systems face several challenges, including limited stowage capabilities, potential disruptions in ground communication, exposure to space radiation, and limitation of some functional capabilities in a microgravity environment.

Behavioral Health and Performance

Crew behavioral health and performance are affected by missions in isolated, confined, and extreme (ICE) environments. Future exploration missions will involve humans moving further away from low Earth orbit (LEO) with longer mission durations and will have a greater risk for behavioral health and performance decrements. These hazards could lead to (a) adverse cognitive or behavioral conditions affecting crew health and performance during the mission; (b) the development of psychiatric disorders if adverse behavioral health conditions are undetected or inadequately mitigated; and c) long-term health consequences, including late-emerging cognitive and behavioral changes. Ensuring crew behavioral health over the long term is essential. Behavioral health standards optimize crewmembers’ health, well-being, and productivity and reduce the risk of behavioral and psychiatric conditions before, during, and after missions.

Bone Loss

Bone density loss in microgravity (skeletal unloading) is a well-documented crew health concern since the Skylab mission, when it was observed that the flight crew had about 1-1.5% mineral loss per month. This was noted as being “significantly faster than normal osteoporotic individuals.” As a result, several technical requirements throughout Volumes 1 and 2 of NASA-STD-3001 provide countermeasures that can aid in the prevention of significant deterioration of overall crew heath.

Cognitive Workload

Cognitive Workload is the user’s perceived level of mental effort that is influenced by many factors, particularly task load and task design. The workload measurement enables standardized assessment of whether temporal, spatial, cognitive, perceptual, and physical aspects of tasks and the crew interfaces for these tasks are designed and implemented to support each other. Application of workload measurement for crew interface and task designs in conjunction with other performance measures, such as usability and design-induced error rates, helps assure safe, successful, and efficient system operations by the crew. Designers need to consider the workload of the user when designing and producing an interface or designing a task. Low workload levels are associated with boredom and decreased attention to task, whereas high workload levels are associated with increased error rates and the narrowing of attention

to the possible detriment of other information or tasks (Sandor et al., 2013). Humans perform best when they are neither bored nor overburdened, and when periods of work and rest are equitably mixed together. Workload assessments should be integrated early and often through the engineering design life cycle so that related design decisions can be made from a data-driven perspective and ensure crew safety and performance.

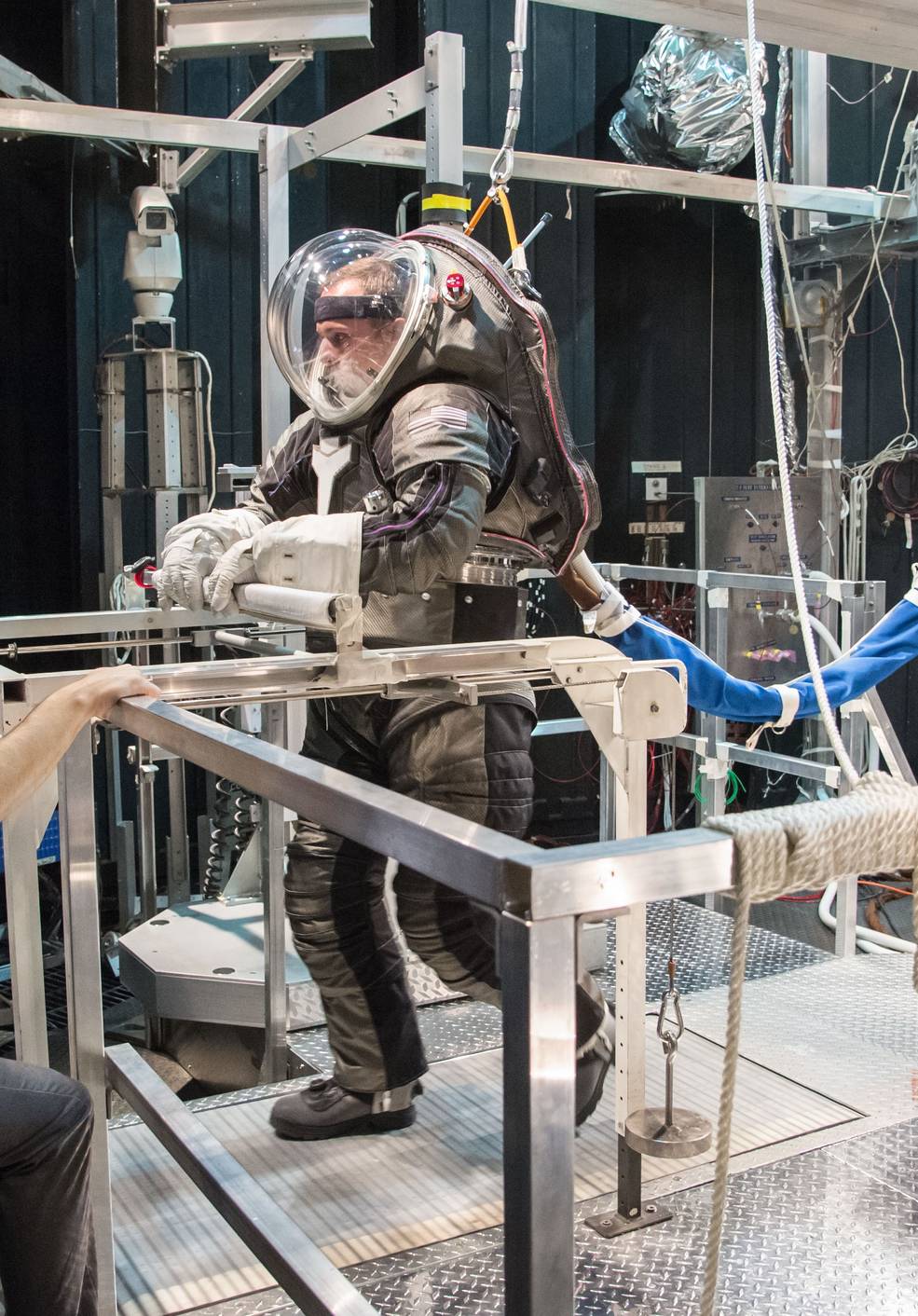

Decompression Sickness (DCS) Risk Mitigation

Denitrogenation protocols (removing nitrogen from the body) are employed to minimize the risk of decompression sickness (DCS), which is the formulation of gas emboli (bubbles) during suited extravehicular activities (EVAs). Moving from a higher pressure to a lower pressure too quickly and without adequate denitrogenation can cause bubbles to form in the body. DCS should also be minimized during offnominal events such as cabin depressurization. If a suit (LEA-Launch, Entry, Abort) is utilized during a cabin depressurization event, it requires sufficient pressure relative to the initial cabin pressure to be effective. DCS mitigation protocols are implemented through the combination of habitat, EVA suit pressure, and breathing gas procedures to achieve nominal mission operations.

Exercise Overview

The human cardiovascular and skeletal muscle systems have evolved to meet the challenges of upright posture in the Earth’s gravitational environment. During spaceflight, astronauts experience altered gravity environments that lead to physiological decrements in aerobic capacity, muscle strength, bone strength, vision changes, and altered vascular motility, which can lead to a decrease in crew performance. Exercise is prescribed to astronauts as a countermeasure to altered gravity and is vital to maintaining optimal crew health and performance. It addresses these decrements and is also used as a countermeasure for orthostatic intolerance and immune and sensorimotor functioning.

Food and Nutrition

Nutrition has been critical in every phase of exploration on Earth, from the time when scurvy plagued seafarers to the last century when polar explorers died from malnutrition or, in some cases, nutrient toxicities. The space food system must provide food that is safe, nutritious, and acceptable to the crew to maintain crew health and performance during space flight. Nutritional standards in NASA-STD-3001 are based on National Institutes of Health (NIH) standards dietary recommended intake (DRI). Achieving and maintaining food system acceptability, nutrition, and safety for space flight is complex and influenced by factors such as availability of mass, volume, power, crew time, food preparation capability, preference foods, resupply, variety, mission duration, and required shelf life.

Mission Duration

Mission duration is a key factor for many of the human system risks of spaceflight. Some risks are already known challenges and will be further exacerbated by increased mission duration. It is also one of the parameters that defines the applicable requirements to the engineering system. As the duration of a mission increases, the physical volume required to accommodate the personal needs of the crew and the mission tasks increases. Long-duration missions can also affect the crews’ behavioral health due to confinement, stress, and isolation. The psychological needs of a long-duration mission drive additional volume and privacy requirements. Designing architecture for long-duration spaceflight missions requires consideration of additional factors that may not be as critical for a short duration mission. Success of a mission and the lives of the crew will depend on reliable systems that are optimal from the earliest phases of design.

Non-Ionizing Radiation

Non-ionizing radiation (NIR) is one of the health risks that astronauts face in spaceflight. Sources of NIR that are monitored in an effort to protect crew include radiofrequency (RF) emitters, natural and artificial incoherent light sources, and lasers. As research and development activities on the International Space Station (ISS) have progressed, NIR sources have expanded to include the use of stronger lasers and more powerful antennas for improved communication capabilities. Current NIR safety requirements are based on terrestrial guidelines, however the spaceflight environment has unique challenges that require a proactive, flexible, and highly adaptive risk management approach that is unique when compared to terrestrially-based NIR safety processes. Hardware design and controls, health countermeasures, and operational controls are all used as part of the NASA’s NIR hazard mitigation strategy.

Orthostatic Intolerance

Orthostatic intolerance (OI) is an abnormal response observed during return to a gravitational environment after microgravity exposure. It is triggered by upright positioning and is caused by an inability to maintain arterial blood pressure and cerebral perfusion. It can result in presyncope and, ultimately, syncope (i.e., loss of consciousness). Specifically in the spaceflight community, OI is a major concern when crewmembers are re- introduced to gravity after landing due to decreased plasma volume and sympathetic nervous system dysfunction. OI must also be considered for standing or upright crew experiencing acceleration loads. A variety of countermeasures can be implemented to mitigate OI symptoms.

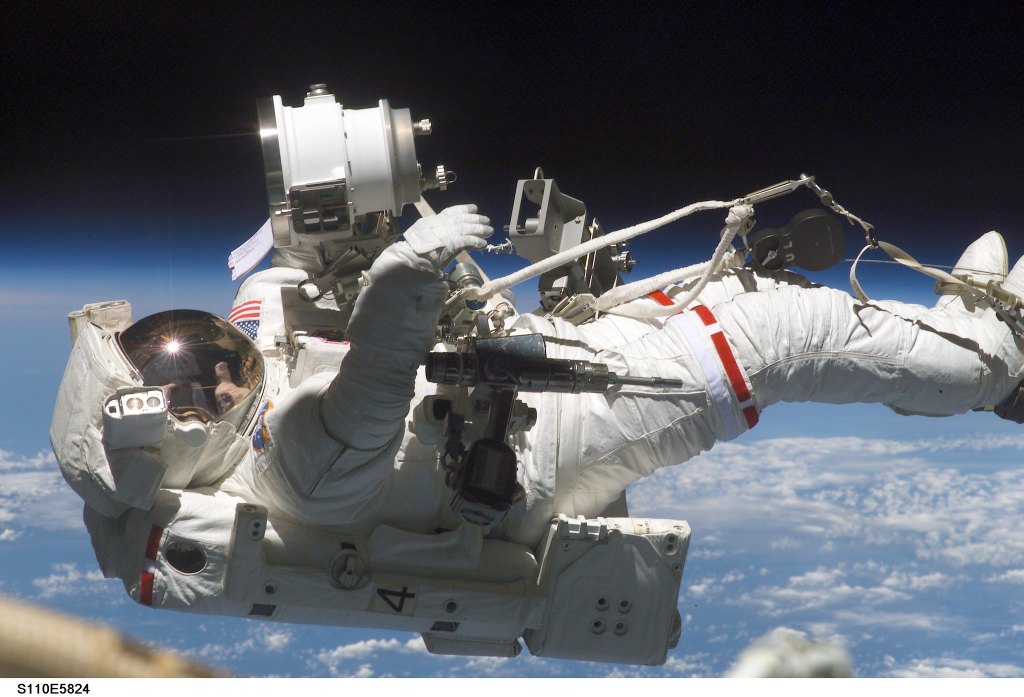

Sensorimotor

The human body is exposed to numerous health hazards throughout any given spaceflight mission, from suborbital spaceflight to deep space exploration, and ranging from short-duration exposure to long-duration missions of months to even years of continuous spaceflight. During spaceflight, astronauts experience altered gravity environments that lead to sensorimotor decrements, often manifesting as motion sickness, spatial disorientation, problems with postural control and locomotion, and fine motor control deficits. These in turn lead to a decrease in overall crew performance, including difficulties with manually controlling a vehicle, extravehicular activities, and ingressing/egressing the vehicle. The purpose of this technical brief is to provide an overview of vehicle and system design considerations, flight rules and mission operations, pharmaceutical intervention, and crew training and assessments that can minimize the adverse effects of sensorimotor degradation that crewmembers experience during spaceflight.

Sleep Accommodations

Astronauts must maintain a high level of cognitive performance during every phase of the mission. Top tier performance depends on the ability to acquire an adequate quantity of daily sleep and the appropriate sleep quality. Previous spaceflight experience has shown that astronauts commonly experience sleep deprivation. Additionally, due to the nature of spaceflight, circadian disturbances are present. Together, these two aspects lead to fatigue and errors while performing tasks. Evidence from short- and long-duration missions and other relevant environments suggests that environmental factors (e.g., noise, temperature, vibration, and light) inhibit sleep and impact well-being in space. Thus, for crewmembers to achieve optimal sleep, they must be provided with a sleep environment that allows them to achieve quality sleep, free of external disruptions.

Space Adaptation Sickness (SAS)

Space Adaptation Sickness (SAS), which includes Space Motion Sickness (SMS), is a well-known problem that affects up to 73% of crewmembers during the first 2-3 days of spaceflight. It is thought to be caused by the body’s neurological and perceptual systems response to the microgravity environment. The severity of crew symptoms varies from mild to severe. SAS symptoms include congestion, headache, back pain, lethargy constipation, and urinary retention. SMS symptoms include malaise, sluggishness, disorientation, impaired concentration, stomach awareness, decreased appetite, nausea, and vomiting. Symptoms are generally worse on initial flights and last 2-3 days (or longer in some crew). Concerns include health decrements (dehydration and weakness) and decreased crew performance. Treatments range from pharmacological to preflight crew training. Symptoms can also appear with the gravity shift upon return to earth called Terrestrial Readaptation Motion Sickness (TRMS) and could potentially affect landing and egress operations. This technical brief describes the theories of causes, symptoms, and treatments provided to crew to help minimize the impact of Space Adaptation Sickness.

Spaceflight Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome (SANS)

Spaceflight Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome (SANS) refers to a constellation of ocular findings including optic disc edema, posterior globe flattening, chorioretinal folds, and hyperopic shifts in refractive error observed in astronauts during and following long-duration spaceflight. SANS etiology is not certain, but altered gravity and fluid shifts resulting in venous congestion and intracranial pressure elevations are the most likely causes. The concerns associated with signs and symptoms of SANS are decrements in vision that can affect inflight crew capability and task performance as well as long-term eye health risks that could result from eye and brain structural changes that develop during spaceflight. In this technical brief we discuss the pathophysiology, and countermeasures being used and studied in order mitigate these risks.

Suited Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

Spaceflight is associated with many factors which may promote kidney stone formation, urinary retention, and/or Urinary Tract Infection (UTI). According to the International Space Station (ISS) mission predictions supplied by NASA’s Integrated Medical Model, kidney stone is the second most likely reason for emergency medical evacuation from the ISS, with sepsis (urosepsis as primary driver) being the third. Alterations in hydration state (relative dehydration), spaceflight-induced changes in urine biochemistry (urine supersaturation), microgravity-induced alterations in fluid dynamics and position of abdominal structures, and changes in bone metabolism (increased calcium excretion) during exposure to microgravity may all contribute to the increased risk of urinary health issues. This medical technical brief describes the conditions of urinary retention, UTIs, and renal stones, and how they are affected by spaceflight conditions as well as outcomes and countermeasures used to prevent them.

Urinary Health

Spaceflight is associated with many factors which may promote kidney stone formation, urinary retention, and/or Urinary Tract Infection (UTI). According to the International Space Station (ISS) mission predictions supplied by NASA’s Integrated Medical Model, kidney stone is the second most likely reason for emergency medical evacuation from the ISS, with sepsis (urosepsis as primary driver) being the third. Alterations in hydration state (relative dehydration), spaceflight-induced changes in urine biochemistry (urine supersaturation), microgravity-induced alterations in fluid dynamics and position of abdominal structures, and changes in bone metabolism (increased calcium excretion) during exposure to microgravity may all contribute to the increased risk of urinary health issues. This medical technical brief describes the conditions of urinary retention, UTIs, and renal stones, and how they are affected by spaceflight conditions as well as outcomes and countermeasures used to prevent them.

Venous Thrombosis in Spaceflight (VTE)

Altered blood flow has been identified in the internal jugular veins (IJVs) of crewmembers concomitant with vessel distension. Inflight ultrasound has revealed that flow in the left IJV may be: (a) antegrade but with lower rates than terrestrial norms, (b) stagnant, and/or (c) retrograde. In rare cases, a thrombus formation has been discovered in the left IJV of a crewmember. NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) convened technical interchange meetings (TIMs) with both internal and external experts in cardiology, vascular medicine and hematology, neurology, radiology, spaceflight medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, ophthalmology, and basic coagulation laboratory science to discuss diagnosed cases of venous thrombosis in spaceflight and to formulate recommendations. Based on the recommendations from these TIMs, NASA developed an algorithm to provide guidance for inflight assessment, prevention, and treatment of thrombus formation in weightlessness.