The Moon is shrinking as its interior cools, getting more than about 150 feet (50 meters) skinnier over the last several hundred million years. Just as a grape wrinkles as it shrinks down to a raisin, the Moon gets wrinkles as it shrinks. Unlike the flexible skin on a grape, the Moon’s surface crust is brittle, so it breaks as the Moon shrinks, forming “thrust faults” where one section of crust is pushed up over a neighboring part.

“Our analysis gives the first evidence that these faults are still active and likely producing moonquakes today as the Moon continues to gradually cool and shrink,” said Thomas Watters, senior scientist in the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington. “Some of these quakes can be fairly strong, around five on the Richter scale.”

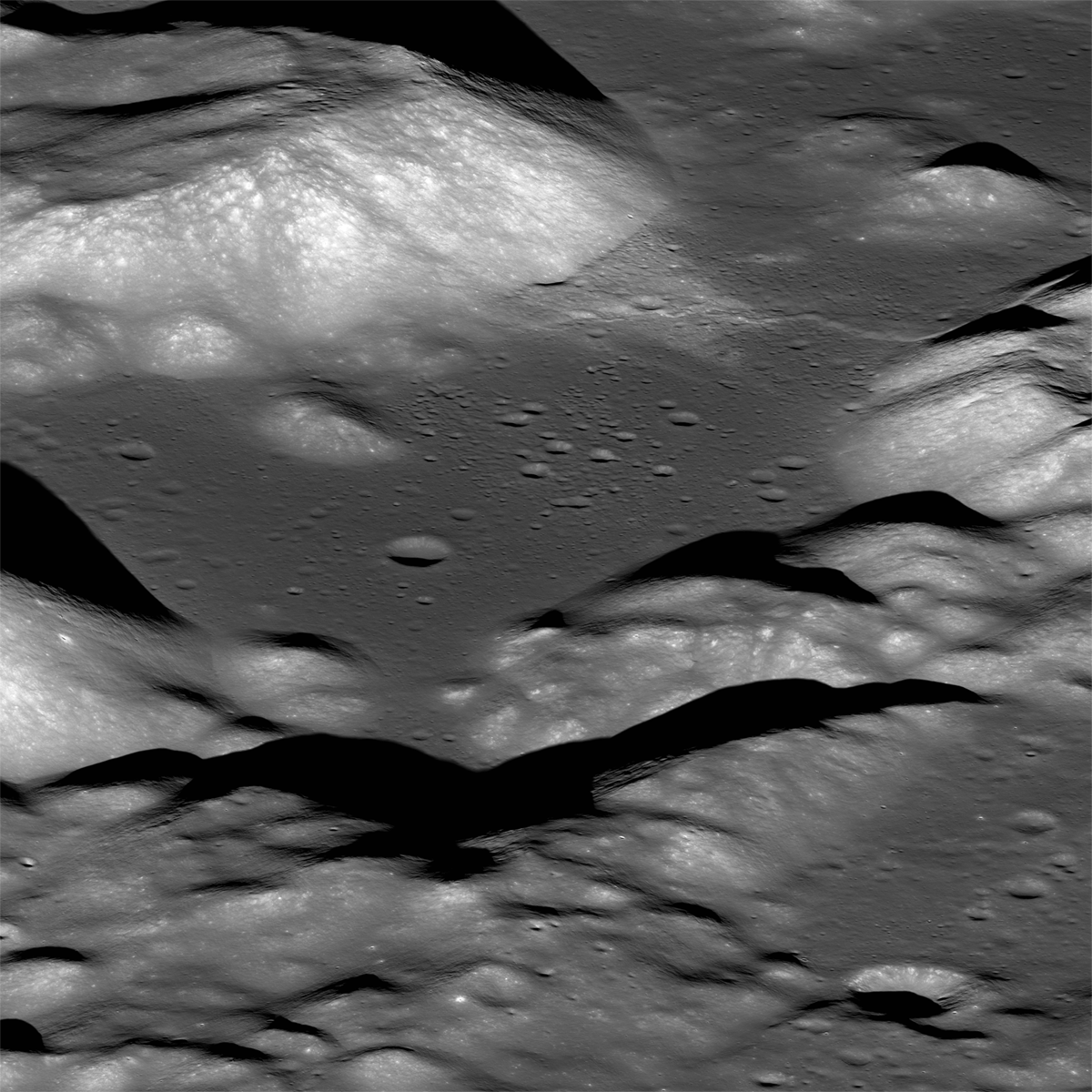

These fault scarps resemble small stair-step shaped cliffs when seen from the lunar surface, typically tens of yards (meters) high and extending for a few miles (several kilometers). Astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt had to zig-zag their lunar rover up and over the cliff face of the Lee-Lincoln fault scarp during the Apollo 17 mission that landed in the Taurus-Littrow valley in 1972.

Watters is lead author of a study that analyzed data from four seismometers placed on the Moon by the Apollo astronauts using an algorithm, or mathematical program, developed to pinpoint quake locations detected by a sparse seismic network. The algorithm gave a better estimate of moonquake locations. Seismometers are instruments that measure the shaking produced by quakes, recording the arrival time and strength of various quake waves to get a location estimate, called an epicenter. The study was published May 13 in Nature Geoscience.

Astronauts placed the instruments on the lunar surface during the Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, and 16 missions. The Apollo 11 seismometer operated only for three weeks, but the four remaining recorded 28 shallow moonquakes – the type expected to be produced by these faults – from 1969 to 1977. The quakes ranged from about 2 to around 5 on the Richter scale.

Using the revised location estimates from the new algorithm, the team found that eight of the 28 shallow quakes were within 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) of faults visible in lunar images. This is close enough to tentatively attribute the quakes to the faults, since modeling by the team shows that this is the distance over which strong shaking is expected to occur, given the size of these fault scarps. Additionally, the new analysis found that six of the eight quakes happened when the Moon was at or near its apogee, the farthest point from Earth in its orbit. This is where additional tidal stress from Earth’s gravity causes a peak in the total stress, making slip-events along these faults more likely.

“We think it’s very likely that these eight quakes were produced by faults slipping as stress built up when the lunar crust was compressed by global contraction and tidal forces, indicating that the Apollo seismometers recorded the shrinking Moon and the Moon is still tectonically active,” said Watters. The researchers ran 10,000 simulations to calculate the chance of a coincidence producing that many quakes near the faults at the time of greatest stress. They found it is less than 4 percent. Additionally, while other events, such as meteoroid impacts, can produce quakes, they produce a different seismic signature than quakes made by fault slip events.

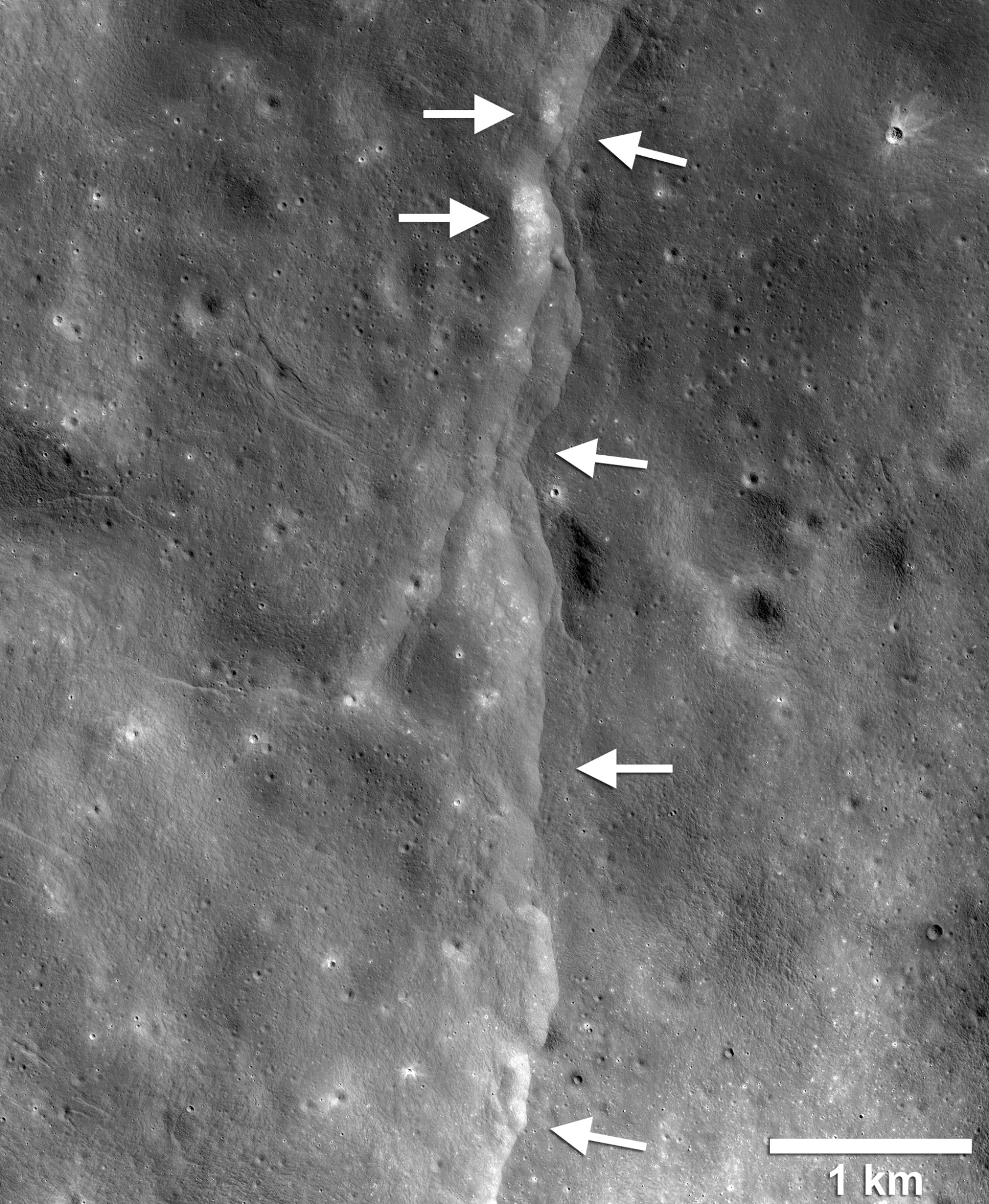

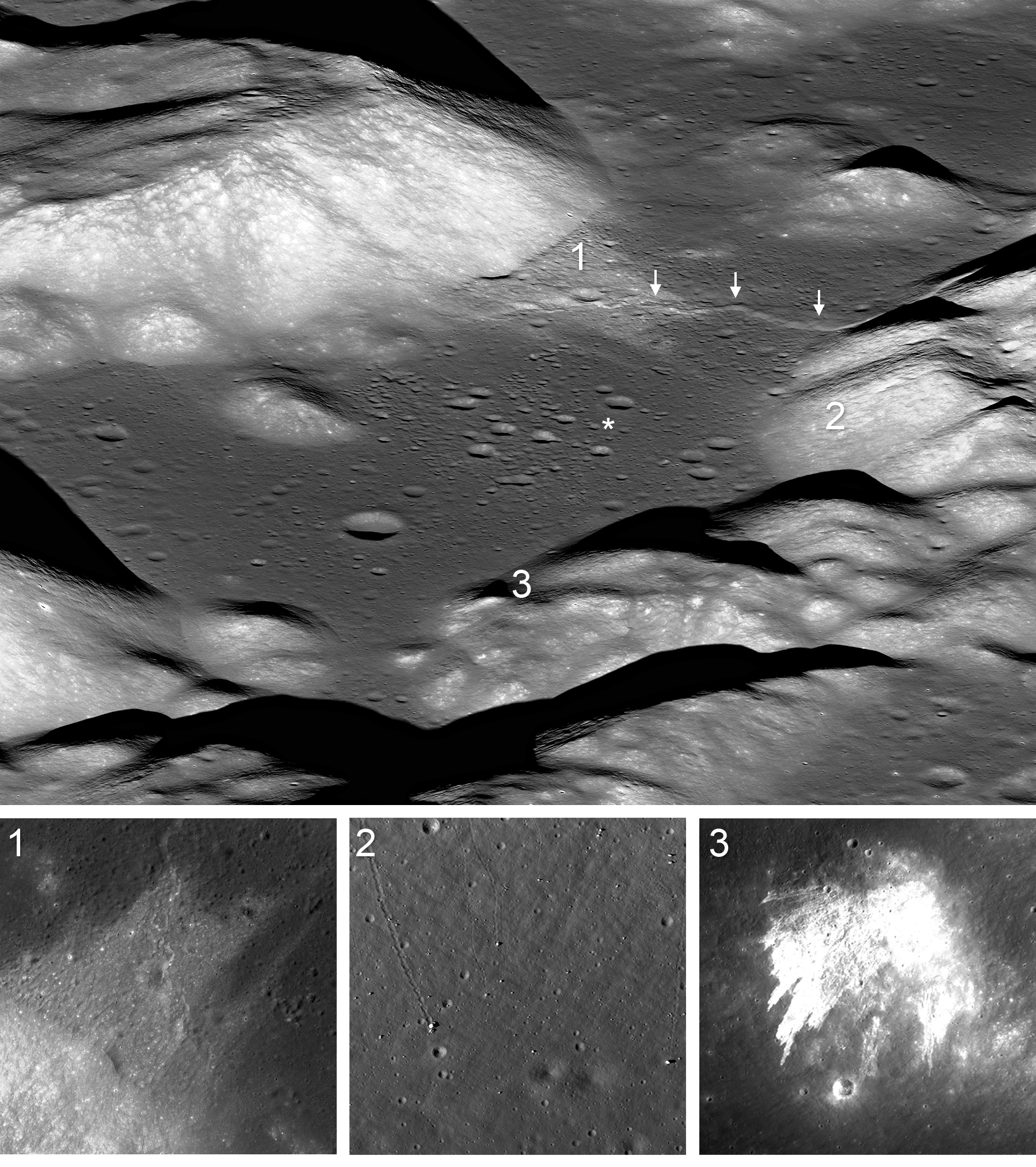

Other evidence that these faults are active comes from highly detailed images of the Moon by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) spacecraft. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) has imaged over 3,500 of the fault scarps. Some of these images show landslides or boulders at the bottom of relatively bright patches on the slopes of fault scarps or nearby terrain. Weathering from solar and space radiation gradually darkens material on the lunar surface, so brighter areas indicate regions that are freshly exposed to space, as expected if a recent moonquake sent material sliding down a cliff. Examples of fresh boulder fields are found on the slopes of a fault scarp in the Vitello cluster and examples of possible bright features are associated with faults that occur near craters Gemma Frisius C and Mouchez L. Other LROC fault images show tracks from boulder falls, which would be expected if the fault slipped and the resulting quake sent boulders rolling down the cliff slope. These tracks are evidence of a recent quake because they should be erased relatively quickly, in geologic time scales, by the constant rain of micrometeoroid impacts on the Moon. Boulder tracks near faults in Schrödinger basin have been attributed to recent boulder falls induced by seismic shaking.

Additionally, one of the revised moonquake epicenters is just 13 kilometers (8 miles) from the Lee-Lincoln scarp traversed by the Apollo 17 astronauts. The astronauts also examined boulders and boulder tracks on the slope of North Massif near the landing site. A large landslide on South Massif that covered the southern segment of the Lee-Lincoln scarp is further evidence of possible moonquakes generated by fault slip events.

“It’s really remarkable to see how data from nearly 50 years ago and from the LRO mission has been combined to advance our understanding of the Moon while suggesting where future missions intent on studying the Moon’s interior processes should go,” said LRO Project Scientist John Keller of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Since LRO has been photographing the lunar surface since 2009, the team would like to compare pictures of specific fault regions from different times to see if there is any evidence of recent moonquake activity. Additionally, “Establishing a new network of seismometers on the lunar surface should be a priority for human exploration of the Moon, both to learn more about the Moon’s interior and to determine how much of a hazard moonquakes present,” said co-author Renee Weber, a planetary seismologist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

The Moon isn’t the only world in our solar system experiencing some shrinkage with age. Mercury has enormous thrust faults — up to about 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) long and over a mile (3 kilometers) high — that are significantly larger relative to its size than those on the Moon, indicating it shrank much more than the Moon. Since rocky worlds expand when they heat up and contract as they cool, Mercury’s large faults reveal that is was likely hot enough to be completely molten after its formation. Scientists trying to reconstruct the Moon’s origin wonder whether the same happened to the Moon, or if instead it was only partially molten, perhaps with a magma ocean over a more slowly heating deep interior. The relatively small size of the Moon’s fault scarps is in line with the more subtle contraction expected from a partially molten scenario.

NASA will send the first woman, and next man, to the Moon by 2024. These American astronauts will take a human landing system from the Gateway in lunar orbit, and land on the lunar South Pole. The agency will establish sustainable missions by 2028, then we’ll take what we learn on the Moon, and go to Mars.

This research was funded by NASA’s LRO project, with additional support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. LRO is managed by NASA Goddard for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. The LROC is managed at Arizona State University in Tempe.

Bill Steigerwald / Nancy Jones

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland

301-286-8955 / 301-286-0039

william.a.steigerwald@nasa.gov / nancy.n.jones@nasa.gov