In mid-1966, Gemini X continued advancing NASA’s capabilities for operating in space with a record-setting, three-day flight. Two astronauts completed rendezvous with two separate targets, retrieved an experiment package from another orbiting object and set a new altitude record for human flight. All were designed as stepping stones in preparation for the Apollo moon landings to follow.

But the spaceflight technology developed at that time continues to play a crucial role today in missions to the International Space Station and planning for the agency’s Journey to Mars.

Like the two previous Gemini flights, the Gemini X plan included rendezvous and docking with a separately launched Agena spacecraft. Additionally, this mission would be the first to include two spacewalks.

The command pilot for Gemini X was John Young, a veteran of the first mission in America’s two-man spacecraft. A naval aviator, he would go on to fly to the moon twice, aboard Apollo 10 in 1969 and Young commanded the Apollo 16 lunar landing in 1972. He later was selected to command the first space shuttle mission in 1981 and the STS-9 flight in 1983.

Pilot for Gemini X was Mike Collins, a U.S. Air Force test pilot. He went on to serve as command module pilot on Apollo 11 in 1969, remaining in lunar orbit as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon.

The Agena launched atop an Atlas rocket on the afternoon of July 18, 1966. Gemini X followed 101 minutes later, climbing into the blue sky on its Titan II launch vehicle.

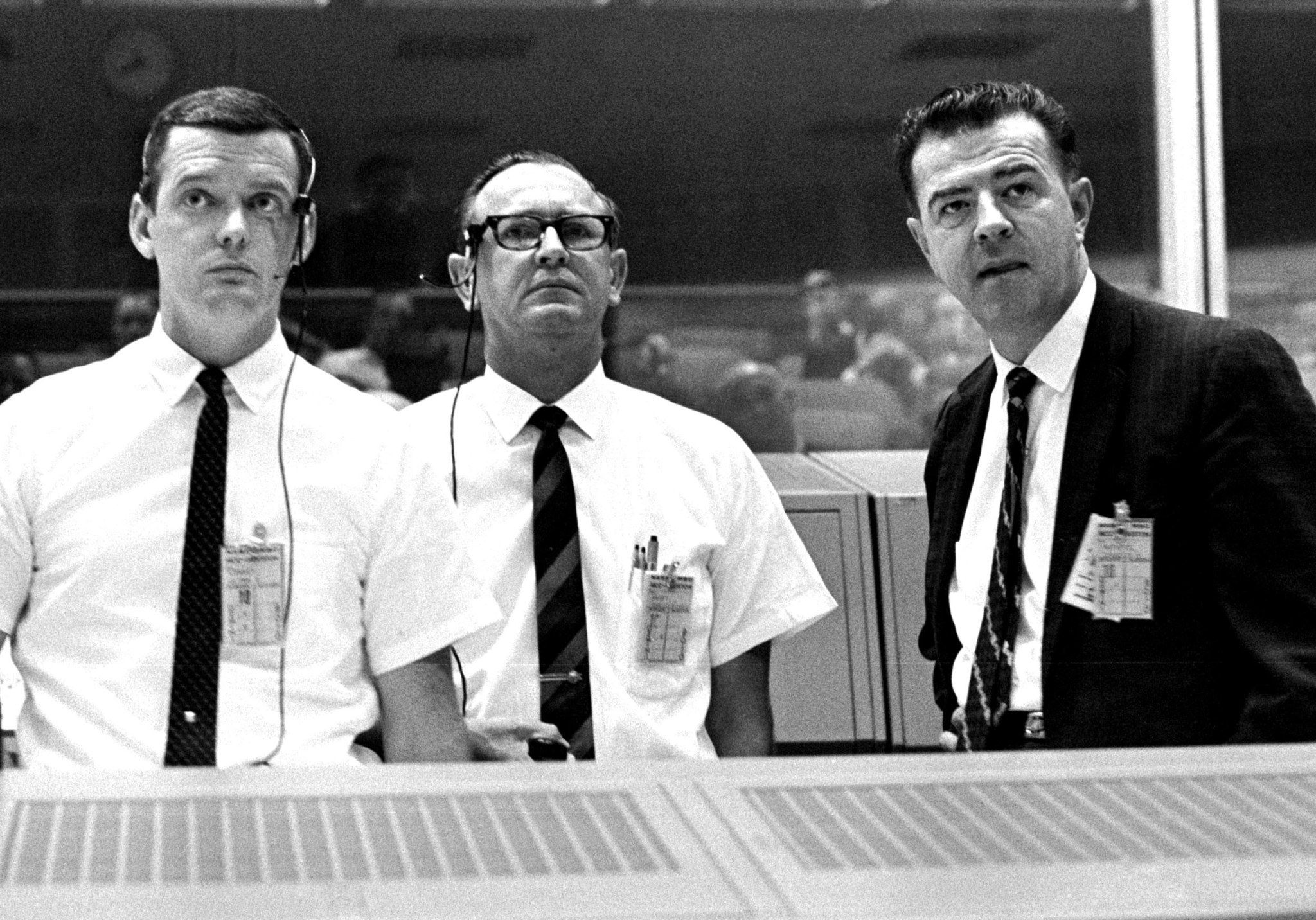

George Mueller, Ph.D., NASA’s associate administrator for Manned Space Flight, had high praise for the launch teams at Cape Kennedy (now Cape Canaveral) Air Force Station, noting the dual launches were near perfect.

“This is a most auspicious beginning,” he said. “It is an excellent demonstration of on-time launch capability. We’re pleased with all the ground support crews.”

Once in orbit, Young and Collins were 1,116 miles behind the Agena target spacecraft. Rendezvous was achieved a little over five hours after liftoff on the fourth orbit.

“Gemini X, what is your status?” asked fellow astronaut Gordon Cooper, the spacecraft communicator at Mission Control in Houston. “Are you there yet?”

“We’re there,” Young said as Gemini X passed over Madagascar off the east coast of Africa. “Our range is about 40 feet.”

Minutes later, they were given a “go to dock” with the Agena from controllers aboard the tracking ship Coastal Sentry Quebec as they passed between the Philippines and Japan – 5 hours, 59 minutes into the mission.

All was well, except the rendezvous required more of Gemini X’s propellant than planned.

“We’re reading 36 percent,” Young reported just prior to docking.

With fuel needed for other portions of the mission, flight director Glynn Lunney directed the crew to skip a planned practice of undocking and re-docking. The fuel aboard the Agena now would not only aid in maneuvering, it would boost Young and Collins to new heights.

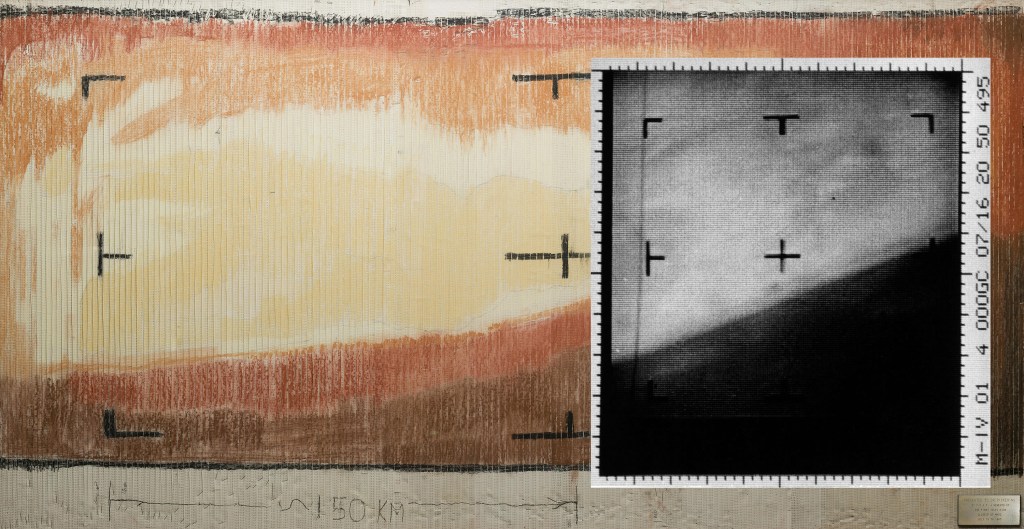

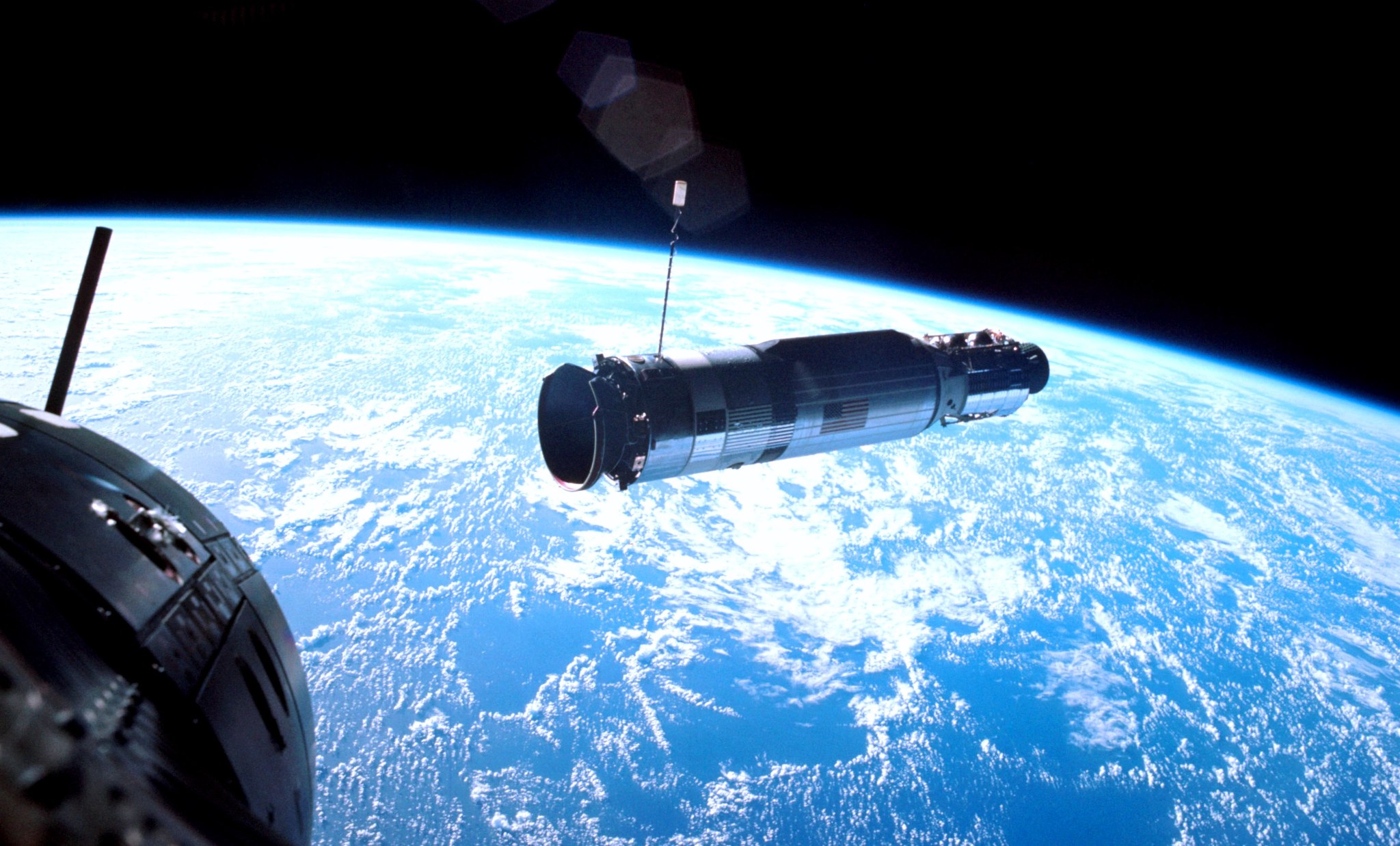

The Agena primary propulsion system engine roared to life with 15,960 pounds of thrust. For 80 seconds, the target vehicle pushed itself and Gemini upward to a record 475 mile altitude. At the time, it was the highest any humans had traveled.

“When that baby lights, there’s no doubt about it,” Collins said.

Young later described the Agena engine firing in detail.

“We were thrown forward (against their harnesses) in the seats,” he said. “Fire and sparks started coming out of the back end of that rascal. The light was something fierce, and the acceleration was pretty good.”

Following a busy day, Young and Collins were ready for the upcoming eight-hour sleep period.

The first task for the second flight day was another firing of their Agena’s engine to lower their spacecraft to the 235-mile orbit of the Agena used on Gemini VIII four months earlier.

After undocking from the Gemini X Agena, fellow astronaut Clifton Williams, the spacecraft communicator in Mission Control Houston, gave the crew an update on the distance to their second rendezvous target.

“At the time you separated from the Agena, your VIII Agena was 138 miles away from you,” he said.

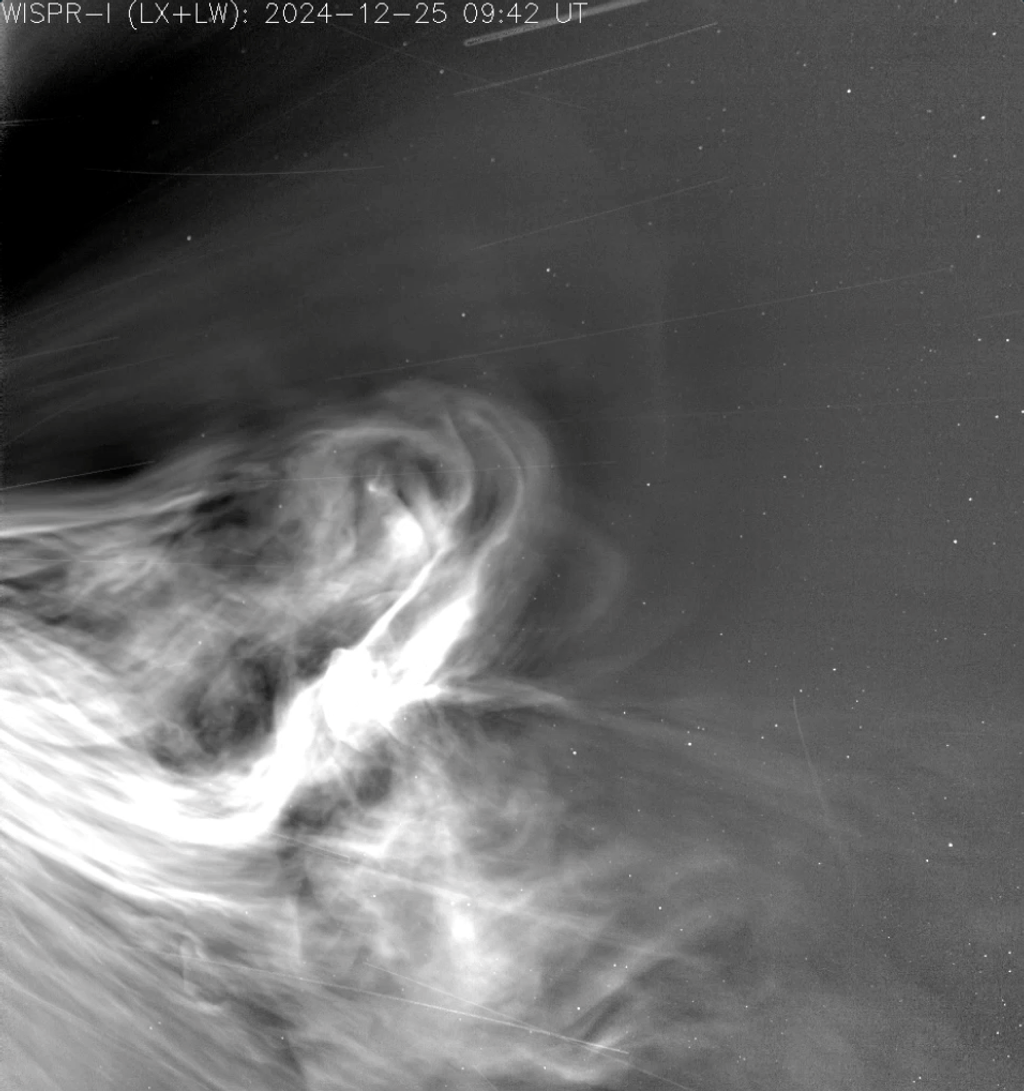

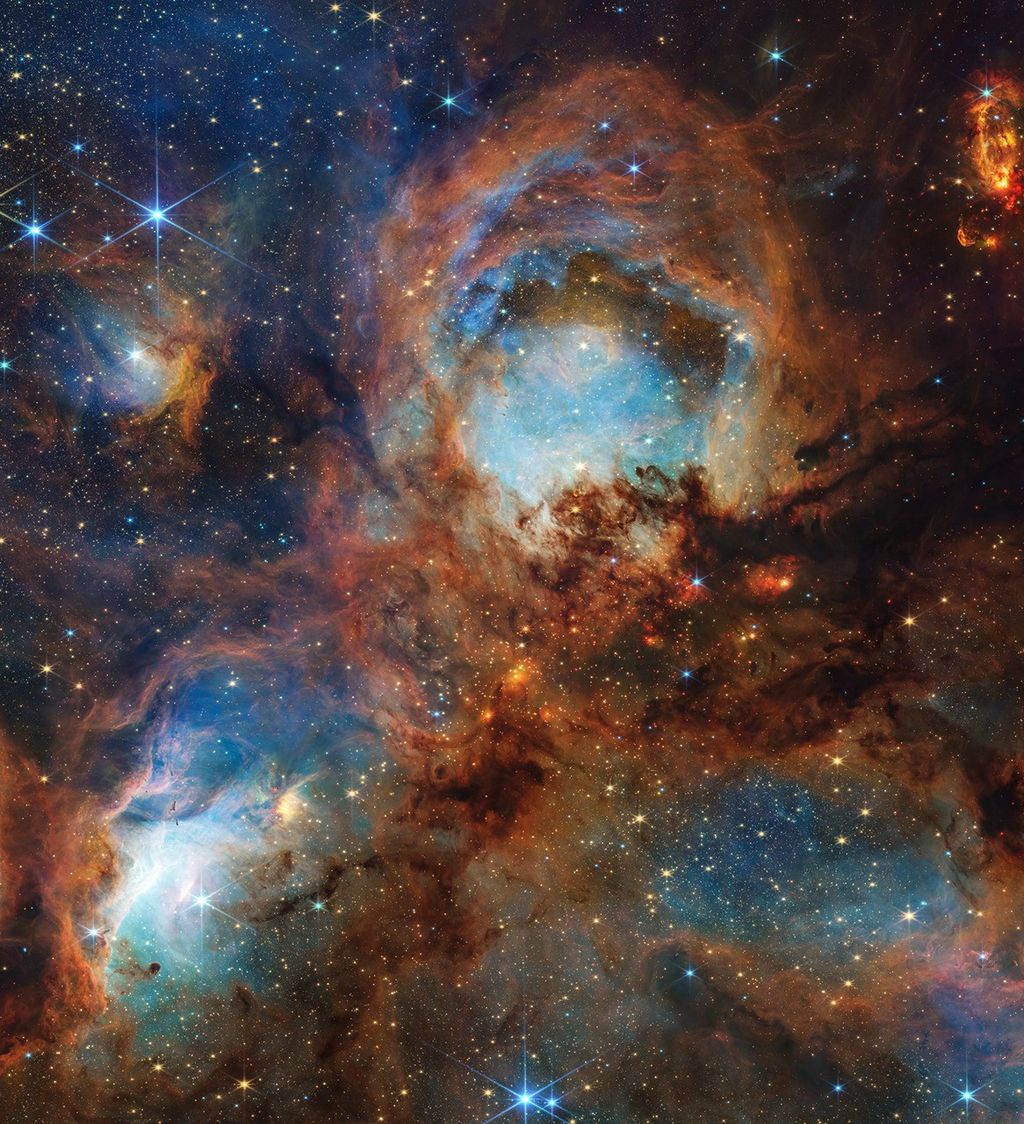

The crewmen then began preparing for Collins’ first spacewalk. His task was to open the hatch and stand on his seat using a 70-mm camera to photograph stars in ultraviolet light. This was important because imaging the stars in the ultraviolet spectrum is only possible outside the Earth’s atmosphere. For 49 minutes he took 22 images of the southern Milky Way.

The first activity of the next day would bring an unprecedented second rendezvous and another spacewalk. As Gemini X closed in on their second target, Young reported to Mission Control.

“I see it dead ahead,” he said. “We have the Gemini VIII Agena in sight. We’ve been watching it for about 5 minutes.”

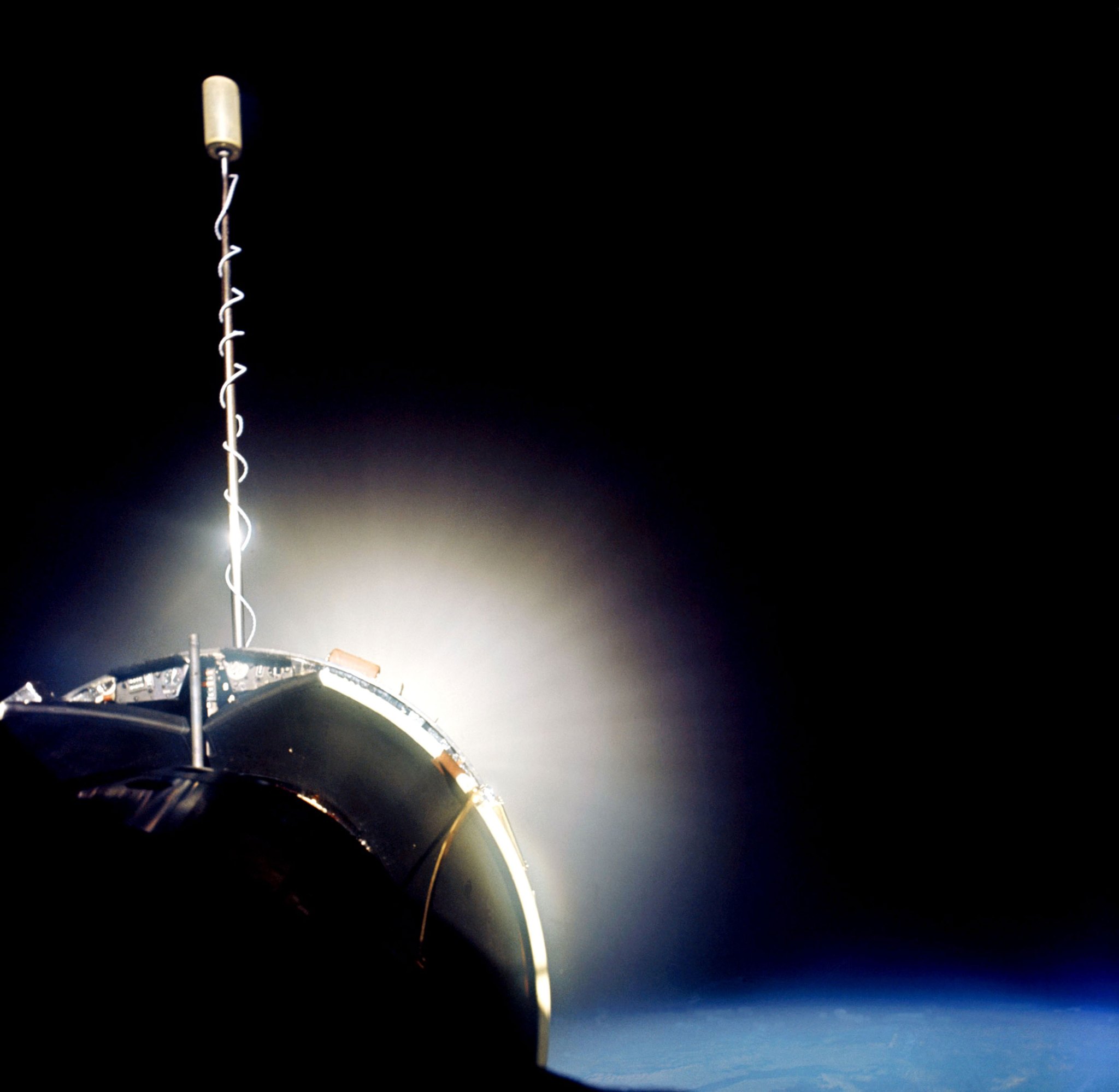

Following a few additional firings of their spacecraft maneuvering thrusters, the Gemini X crew were 10 feet from the Gemini VIII Agena. The rendezvous was completed just 90 minutes prior to the start of the second spacewalk. The fact that the Agena was stable and in good condition was good news. Plans called for Collins to retrieve an experiment package from the side of the now dormant spacecraft.

He also planned to use a nitrogen-propelled hand-held maneuvering unit (HHMU) to move himself between the Gemini and Agena. It was similar to the “zip gun” used by Ed White on Gemini IV a year earlier. This one was designed to be plugged into the adapter section behind the spacecraft hatch, thus providing more fuel for the HHMU.

As Collins floated free from his Gemini hatch, he reported some of the same frustrations as Gene Cernan on Gemini IX.

“Everything is going well,” he said, “but, it’s taking a lot more time to do each item than I had anticipated.”

Collins plugged in the nitrogen fuel line for the HHMU and prepared to move to Agena VIII. He then moved to the Agena and attempted to grasp the docking cone, however he discovered it was impossible since it was smooth and had nothing to grasp.

“When I translated over to the Agena, I found that the lack of hand holds is a big impediment,” Collins said.

Young reported to controllers at the Hawaii tracking station that Collins was able to hold some wire bundles on the Agena and was successful in retrieving a micrometeorite collector experiment.

As Collins began a planned activity to further test the HHMU, he noted that while retrieving the micrometeorite experiment and moving to and from the Agena, he inadvertently lost his Hasselblad camera. To date, this is the only spacewalk not captured with photographs.

Young’s challenge during the spacewalk was “station keeping” the spacecraft. That is, ensuring Gemini remained properly positioned in close proximity to both the Agena and his spacewalking pilot while not bumping either. All this maneuvering was using propellant. Mission Control noticed that the already low fuel supplies were quickly diminishing.

“We don’t want you to use any more fuel (for station keeping),” the Hawaii spacecraft communicator told Young.

“Then, we’d better get Mike back in,” Young said.

The 90-minute spacewalk was terminated after only 39 minutes.

About an hour later, Collins’ hatch was opened again for about 3 minutes to toss out the 50-foot umbilical and other no longer needed equipment, freeing up space in the already cramped cockpit. The umbilical provided oxygen and communications while keeping Collins connected to the Gemini spacecraft.

On the last day of the mission, retrofire brought Young and Collins down 2 days, 22 minutes after liftoff, splashing down only 3.5 miles away from the targeted landing point. Once again, the Gemini spacecraft was seen descending under its parachute on live television using a satellite antenna on the deck of the recovery ship, the USS Guadalcanal.

“John, you’re on television,” Mission Control radioed up to the crew.

Guadalcanal control personnel soon reported the same, except they were watching the nearby skies.

“Gemini X, Guadalcanal Control. We have you in sight,” onboard controllers said.

Young and Collins were picked up by a recovery helicopter and delivered to the deck of the ship to the cheers from the U.S. Navy crew on the carrier.

The overall performance of the astronauts, mission support teams, the two launch vehicles, Gemini spacecraft and Agena target vehicle all earned high praise following the flight.

“Gemini has fully matured,” said Chuck Matthews, NASA’s Gemini Program manager, summing up his appraisal of the flight.

“The flight contributed significantly to the knowledge of manned spaceflight,” NASA’s official post-mission report stated, “especially in the areas of rendezvous, docked maneuvering with large propulsion systems, extravehicular activity (spacewalking), and controlled re-entry.”

By Bob Granath

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the seventh in a series of feature articles marking the 50th anniversary of Project Gemini. The program was designed as a steppingstone toward landing on the moon. The investment also provided technology now used in NASA’s work aboard the International Space Station and planning for the Journey to Mars. In September, read about a first orbit rendezvous. For more, see “On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini.“