Crew members aboard the International Space Station conducted a variety of scientific investigations during the week ending Sept. 15, 2023, including the ESA (European Space Agency) investigation Sleep In Orbit.

Sleep is related to health, well-being, and cognitive performance. Poor sleep quality can have immediate negative consequences, including problems with attention, concentration, learning, memory, problem-solving, decision-making, and judgment. Long-term effects of poor sleep are less clear, but there is mounting evidence that ongoing poor sleep increases the risk for cognitive decline and dementia. Living in zero gravity and in an artificial day-night cycle influences circadian rhythm and sleep patterns.

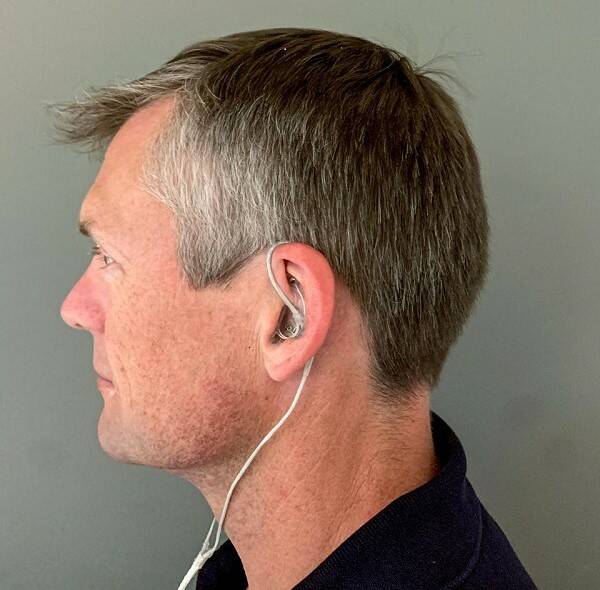

Sleep In Orbit studies the physiological differences between sleep on Earth and in space by conducting sleep monitoring using ear-EEG (electroencephalography). Ear-EEG is a method to record EEG signals from electrodes placed in the ear that offers an advantage over alternative recoding methods due to its minimal impact on sleep, enabling it to be used for long-term sleep monitoring.

A baseline picture of the individual astronaut’s natural sleep on Earth is established based on sleep recording before and after their mission. This baseline is then compared to the crew member’s sleep patterns observed aboard the space station. Gaining insight into astronauts’ sleep physiology in space enables the implementation of preventive measures to mitigate the adverse effects of poor sleep and can offer unique insights to researchers in health sciences.

Dreams, another ESA investigation, uses the Dry-EEG Headband, an effective and comfortable solution to monitor astronaut sleep quality during long-duration spaceflight. The device allows astronauts to monitor sleep wherever they sleep and over several nights. The crew members can receive feedback such as sleep duration, sleep stages, heart rate, and number of awakenings. The raw data is also available to research teams for further analysis. Combined with a dedicated application, the headband can also produce sounds that can be used for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy that could help prepare the body and mind to fall asleep.

Maintaining synchronized circadian rhythms is important to health and well-being. Circadian Rhythms, an ESA investigation, studied the role of synchronized circadian rhythms, or the “biological clock,” and how it changes during long-duration spaceflight. The investigation also addressed the impact of a non-24-hour light-dark cycle, reduced physical activity, changes in body composition, and/or changes in body temperature regulation while living in a microgravity environment. This investigation led to studies evaluating the validity of alternative approaches in describing circadian rhythms using non-invasive core body temperature measurements.

Circadian Light, an ESA investigation, tests that a new lighting system aboard the space station to help astronauts maintain an acceptable circadian rhythm. The light system improves the current lights on station by introducing automation, gradual changes in the light spectrum, and variation from day-to-day to better mimic the variable nature of natural lighting found on Earth. This technology could help enhance cognitive performance and improve physical and mental health through varied and gradually changing lighting sequences and settings.

Sleep studies on the orbiting lab date as far back as the shuttle days on early expeditions to the space station. Sleep-Short examined how space flight affected astronauts’ sleep patterns during space shuttle missions. Subjects wore a small, lightweight activity and light-recording device called Actiwatch and kept daily sleep logs to evaluate the amount and quality of their sleep and alertness for the mission duration. Data from this research showed crew members on space station missions obtained significantly less sleep during spaceflight compared to their first week post-mission.

A later version of the the Actiwatch called Actiwatch Spectrum Plus system is currently being used on station to collect data for the Standard Measures study. Standard Measures collects a set of psychological and physiological measurements representative of many human spaceflight risks, from astronauts before, during, and after long-duration space station missions. Data collected under the Standard Measures experiment includes a questionnaire used both post-sleep and pre-sleep with items focusing on sleep amount, quantity, and quality and, mood, team cohesion, and performance. The study also includes analysis of blood, urine, feces, saliva, and body swabs. The Standard Measures project populates a data repository to enable high-level monitoring of countermeasure effectiveness and interpretation of health and performance outcomes to support future missions.

Sleep-Long, another early experiment, examined whether sleep-wake activity patterns are disrupted during long-duration stays on board the space station. Researchers found that circadian misalignment of scheduled sleep occurred approximately once out of every five sleep episodes aboard station. When crewmembers’ sleep episodes were misaligned, they slept nearly one hour less per night and reported poorer sleep quality. Astronauts were more likely to be circadian misaligned during critical operations, such as when a vehicle was docked with station. Countermeasures based on the findings of this study improve sleep during missions, which in turn helps maintain alertness and lessens fatigue of the crew during long-duration space flights.

Alertness of crews on station is important because sleep restrictions, residual effects from sleep medications, changes the sleep/wake cycle, and effects from spacewalks can cause fatigue and degrade astronaut performance. Reaction Self Test, a previous study, was a portable, five-minute task that enabled astronauts to monitor the daily effects of fatigue on performance while in space. Periodically during the mission, and in association with major events, an astronaut performed a reaction-time test on a computer to measure changes in responses. Results showed that shorter sleep sessions (six hours or less) were associated with slower psychomotor speed, higher stress, and more tiredness. These findings underscore the importance of adequate sleep for improved health and performance during space missions.

Understanding sleep patterns in space and the effects of long-duration missions on crews’ biological clocks could help mitigate the adverse effects of poor sleep, improving performance and health. These studies also provide a unique comparison for sleep disorders and provide tools and data to improve sleep quality back on Earth.