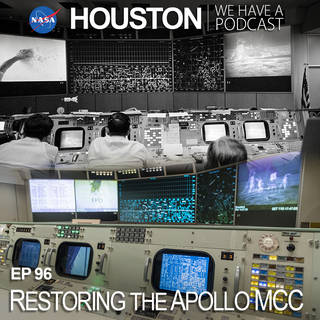

“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

For Episode 96 Sandra Tetley and Adam Graves discuss the journey of restoring the historic Apollo Mission Control Center to look and feel exactly as it did in July 1969 during the moments before, during, and after the moon landing. Ben Feist then focuses on the cleanup of the audio tapes for the restoration project. These podcast interviews were recorded on April 3, 2019 and May 6, 2019.

For more of our Apollo Podcasts check out the “Houston We Have a Podcast: Apollo 50th Anniversary” webpage!

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, We Have a Podcast. Welcome to the official Podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 96, Restoring the Apollo Mission Control Center. I’m Gary Jordan and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers and astronauts all to let you know the coolest information about what’s going on right here at NASA. So if you’re following along with our episodes you’ll know that we’ve been revisiting some of the historic Apollo missions in celebration of their 50th anniversaries. And we’re coming up on a big one, the 50th anniversary of the mission that put the boots of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon. There’s a lot of work being done in celebration of this anniversary. And today we’re going to be discussing one of the more ambitious projects, restoring the historic Apollo Mission Control Center. This includes the mission operations control room 2 more commonly known here as MOCR- 2, the visitor’s viewing room and the simulation control room and the room called the bat cave, super cool, and we’ll get into what that is. Many human space flight missions were controlled out of this center, most of the Gemini and Apollo missions including Apollo 11, the first landing of humans on the moon. The building where all of these live within the Johnson Space Center is called Building 30 which was given national historic landmark status in 1985. It’s been toured over the years, hundreds of people walking in and out. And through that came more wear and tear on this national icon. Soon it just wasn’t the same as it used to be. Now we’re nearing the end of a project spanning six years to restore this historic landmark to look exactly as it did in July 1969 capturing the essence of what it was like five decades ago during some of the greatest moments in human space exploration. Today we’ll be talking more in depth about the journey thus far to restore this historic landmark with Sandra Tetley and Adam Graves. Sandra is a Historic Preservation Officer and Real Property Officer here at the Johnson Space Center. And Adam is the lead for the project based with the company GRAVitate. These folks are at the forefront of this monumental project set to be complete later this month. A big part of this project is allowing visitors to experience a moment in Apollo history not only by being able to see this restored setting but by playing audio from Apollo 11 that had been recently digitized. Houston, We Have a Podcast host Pat Ryan takes over towards the end of this episode to chat with Ben Feist, a web developer among other things who helped process this recently recovered audio from Apollo Mission Control and bring it to life as part of this experience. And this is a very exciting topic so let’s jump right into it with Mrs. Sandra Tetley and Dr. Adam Graves first, and then wrap up with Pat’s conversation with Ben Feist. Enjoy.

[ Music ]

Host: Sandra and Adam, thank you so much for coming on to talk about this great project that’s happening with the Apollo Mission Control Center.

Sandra Tetley: Right, thank you for having us. We’re excited.

Adam Graves: We really appreciate it.

Host: So we’re in the final stretch of this ambitious project being set to complete later this month. We’re aiming for June, hopefully that sticks. How are you guys feeling right now in the home stretch?

Sandra Tetley: Pretty good. We’re on schedule. There’s a few things that have come up, just little things, coordination mainly. But we’re feeling good, we’re excited. It’s starting to come together.

Host: And with a project thing long, we’re talking six years, this is very exciting for this to all come together. Of course there’s going to be things along the way that change, but this is very cool. I wanted to start by taking it all the way back really six years ago. How did this all start? When did we start really considering let’s restore this historic landmark?

Sandra Tetley: So back in March of 2013 I applied for a grant with the National Park Service Heritage Program. And that’s because Building 30 is a national historic landmark. And so what I applied for was $5,000 to do some sort of video or something for the visitors to kind of experience the moon landing. And the Regional Director of the Park Service called me and was very interested in the project. And so they came down and talked to me, and we showed them the Mission Control in its state of disrepair. And so they offered me $20,000 to do a historic furnishings report. And then they would put in the other $20,000. And so they had it commissioned. And what that is, a historic furnishings report is a very in depth, detailed analysis of the Mission Control Center from what it should have been or what it was to how it would — everything we would need to do to restore it. And so from there we held a workshop with the Park Service to kind of bring in the stakeholders, and that was the beginning of it. They felt very strongly that it is of such world importance as a historical site that they felt very strongly that we needed to restore it. So that’s how it started.

Host: And it definitely is because let’s go right into that. What was the condition? What were we looking at? What were the rooms and the elements that we were looking at before we even started restoring it?

Sandra Tetley: So the room — about in the mid 90s after they moved to Building 30 South the room was just unoccupied. The consoles were not lit up or anything. There was nothing on the consoles, no documents or anything. And it was open to whoever could get into 30 could go and sit at the consoles and dial the phones, press the buttons, you know, do whatever they wanted to. Visitors from Space Center Houston went in the viewing room, and then level 9 tours and VIP tours would go on the floor. And so it was not really ever maintained as far as upkeep. The did do some maintenance when chairs would break or something like that. But it was really not kept in any sort of fashion that it should have been.

Host: Yeah, it was kind of just people can go in and do whatever they wanted it. But it wasn’t really treated as a important place in history.

Sandra Tetley: Right.

Host: And that’s where this kind of came in. Because we want this to look and feel and be treated as an important place in history, right. So when you’re talking about this room, people coming in and touching, what is the room?

Sandra Tetley: So the room we call it the Apollo Mission Control Center. There’s actually two Mission Control Centers, MOCR-1 which is on the second floor, and then MOCR-2 was on the third floor. So the Mission Control Center includes the MOCR which is the Mission Operations Control Room. That’s the room with the consoles. Then the visitors viewing room or VIP room which was the seating that was behind the room and had the big glass windows so the family members and dignitaries would sit in there and watch what was going on in the MOCR. Then the simulation control room which is where the simulators would be, and they’re the ones that when they would test and do simulations, they were the ones that would send them all the error messages and all the problems, and so that was the simulation room. And then the bat cave is actually the room behind the large summary display screens that included all of the projectors and the timing systems and the clocks at the very top. And so we call that the bat cave because it’s all black. And so those four rooms are what we term the Mission Control Center.

Host: Okay, the least attractive room visually is the coolest sounding one, the bat cave.

Sandra Tetley: It is cool.

Host: All right, so those are all the elements to really capture this part of history. And these were all the things that you were looking at. Now obviously we’re years into the project. All the proposals, the written, the things you wrote down of here’s what we want to address, those started to happen. Talk about that process where we went from a proposal, what do we need to fix, to let’s start restoring this Apollo Control Center.

Sandra Tetley: Yeah, it didn’t work quite that easily.

Host: Of course, of course.

Sandra Tetley: Yeah. So, there was a lot of stakeholders that wanted to control the project and from Flight Operations to External Relations, Space Center Houston. And so as a national historic landmark, in order to restore the national historic landmark, it needs to be done under the Secretary of the Interior standards for restoration. And so, of course, none of those people have those qualifications. So I pushed to make sure it got under my contract, and that’s where Adam comes in. And so we did a lot of work on — the historic furnishings report gave us the basis, and from that they did the in depth research that we needed to do. And you want to go into that and tell them all that?

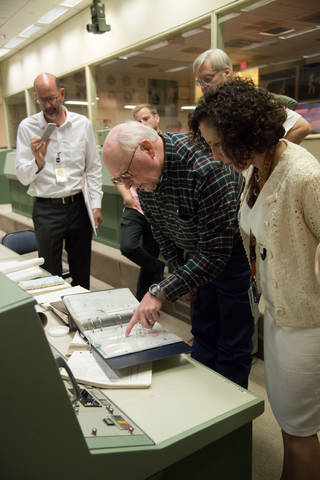

Adam Graves: Yeah, of course. So, you’re right, the historic furnishings report really laid that foundation for just kind of initial assessment. I know when I went in the very first time you get goose bumps, and you know, I’m there on a job so, okay, I’ve got to get over all of this and start looking around and look at the condition. And it was pretty rough. So thank goodness we have the furnishings report to start from. But then you start identifying some of the holes in that furnishings report, looking around at some of the materials that have been replaced over time. And then we hit the libraries and the archives and the photographs and the videos and get all of this information. And then we did interviews with how many?

Sandra Tetley: I think there was about 25.

Adam Graves: Twenty five flight controllers we did interviews with in the room and learned what they did and what buttons on the consoles were lit the most or they interacted with most. Then we take what they say even about lighting in the room, you know, what was the overall sense of lighting, was it dark or was it light, all these specific details so that we can reconstruct that when we get to that point. At that point we weren’t sure are we even going to be funded to do this work. We just know there’s a lot of work that needs to be done. And there’s a lot of details that have to go back to the original because, you know, that room was used after Apollo and through shuttle or for a few missions in shuttle and like that. So we had to kind of go backwards in time and also verify some of the things that the flight controllers. Recollection is different from reality in some cases. So where we could we used photographs and videos. And where we couldn’t the interviews came in really handy. So we had just extensive, extensive research to get all that done.

Host: Yeah, really this report was capturing what was wrong, what were some of the things you need to fix, what has changed over time. Because like you said the room was in use until the early 90s or mid 90s.

Sandra Tetley: Mid 90s.

Host: Mid 90s. So things obviously change over time. But really trying to get a sense of what it was like. And correct me if I’m wrong, you’re restoring it back to the Apollo era.

Sandra Tetley: Yes.

Host: To what it looked like in the Apollo era. That’s the idea. Those are the interviews, the images that you really want to capture, what did it look like in the 60s.

Sandra Tetley: Right.

Adam Graves: That’s exactly right. Yeah, we’re looking to actually even more specific, Apollo 11 during landing and the EVA and recovery. So we want everything to be specific to that, even that shorter time period. Of course, the consoles we’re doing those Apollo 15 configuration. And the lighting on the buttons and the monitors and everything is — we were shooting for Apollo 15 as that’s a piece of history that we wanted to preserve. The flight controllers indicated that was a very important time for technology in the room during the Apollo area. So this was the height of the technology of Apollo and wanted to preserve some of that. So the consoles will be a little bit different in terms of the Apollo era, but everything else is 11. What’s on the console itself is 11. What’s the screens it’s 11. Everything, lighting levels, everything.

Host: Yeah, you get a feel for it. But it sounds like what the flight controllers even wanted was even during Apollo 11 there was still some work to be done to get to the level that they wanted, that peak of technology during Apollo 15. And yes, I can understand why they would want that to be highlighted. But the moment itself being Apollo 11 obviously one of the biggest moments in human history.

Sandra Tetley: Right.

Adam Graves: Exactly.

Host: So, yeah, you want those on the screens.

Sandra Tetley: Exactly.

Host: All right, so how about this process that you’re talking about of tracking all of the changes over time, of what needs to be updated, of these interviews, these photos, how long did that process take?

Adam Graves: Well, in some ways it’s still ongoing.

Adam Graves: We learn something new almost every day. Someone will come out of the woodwork that used to work here and says, oh, I have this or here’s a document that maybe you’ve never seen before. So really since the beginning to present day. And I imagine for the next couple months even we’ll still see some last minute things that really could add to the experience.

Host: Okay. So then what about to actually start restoring things. Now you’ve identified some things. We want the consoles to be Apollo 15, you want these on the screens. So what about actually getting these pieces, these historic pieces to the moment in history that you want to get them to? Where do you go? Where do all these pieces go?

Sandra Tetley: So Adam put together an excellent team basically. And we went out now — and the console sort of is an interesting story because somebody had referred them to me to review the consoles when we were kind of first gathering and getting things going. And then also you’ll have to tell him your story. So we selected them because they have expertise. They have actual Apollo era consoles from MOCR-1.

Host: This is the Kansas Cosmosphere?

Sandra Tetley: Right, Kansas Cosmosphere.

Host: Okay, okay.

Sandra Tetley: And so they are very familiar with it, and they know — they’re familiar with the details and the design, and they have the expertise to restore those. So they were chosen to restore all of the consoles. And so they’ve taken them up to Kansas to their shop, and they’ve been working on them for over a year now. And so they’re expected to come back. But you can tell him your story.

Adam Graves: Yeah, so their heading down the right path of how do we move from this research and get more research and get the right people involved? We had to put a team together. Not one person is big enough or smart enough to figure this monster out. So, yeah, she had heard of the Cosmosphere but I hadn’t. And I had some ideas of some of the experts that might be, you know, we might reach out to for this project. But I got to thinking one day, I think I just woke up with this idea like, okay, I’ve seen the Apollo 13 movie, and I know I’ve seen in that movie a Mission Control Room. So how did they build this? And so I went to the movie and I looked through all the credits, and I find the art designer, the production designer and I contact him. I start looking on the internet. I’m like, okay, how am I going to get in touch with this Michael Corenblith guy? And so I looked for an agent page and that came up with nothing. And I was like, okay, maybe he’s on Facebook. So I went on Facebook and he was. I found the guy and I sent him a Facebook message, and the next day he responded. And he’s like this is great that you’re doing this. And I’d be happy to help if I can, but I can’t believe it’s been 20 years since the Apollo 13 movie, but this is amazing. But he indicated that he had used the Cosmosphere to build some of those consoles. So I was like, all right, great, now I can go hunt this out. So that was one part of the team for the consoles. And then we have this big amazing room full of other things that aren’t consoles.

Host: Right.

Adam Graves: I just knew putting this team together that it was important that I used people in Texas to get this work done, local people that everyone has a story from Houston that involves Johnson Space Center. So I reached out to the historic societies in Dallas and Austin and San Antonio and Houston, and had conversations with a lot of these folks that have done the historic courthouses in Texas. Which was in a way with the materials, the carpets, the wallpapers, things like that, things that I knew were kind of similar just started vetting through those list of people and finally found the Stern and Bucek team here in Houston that has done a lot of that work. So we got with them. And they have a number of subcontractors as well that kind of rounded out the rest of the team.

Host: Okay, wow, all right. So that’s a ton of research. I’m trying to get my mind around all of the different elements that need to come together. Just the Cosmosphere you said was the consoles. Then you’ve got all these other components. You’ve got the rooms. You’re talking windows, ceilings, floors, carpets.

Adam Graves: And we’re talking carpenters and painters and all sorts of things here that have experience doing historic preservation work.

Host: Yes.

Adam Graves: Which is even trickier.

Host: In Texas, right?

Adam Graves: Yes

Host: You’ve got all these different like requirements and things you want to do. So when did this process start? You’re searching for all the right people to do it. Now you’re in the middle of let’s go and actually restore some of these elements. When did this start?

Sandra Tetley: Well, the actual work didn’t even start until October of 2018.

Host: Oh, wow, very recently.

Sandra Tetley: Oh, yeah. I mean because of the funding and because of all the politics involved we took an 18 month project, we estimate 18 to 24 months, and we’re cramming it into that nine months. And we are really literally cramming. But like Adam said it’s been real interesting. We can tell you the story of the carpet and the wallpaper which are probably — and the ceiling tiles — probably the most interesting stories that we have.

Host: Please.

[18:36]

Sandra Tetley: When we were doing research on the carpet we didn’t know — it had already been re-carpeted and re-wallpapered. So we didn’t have any records of what it was or any of that. We could go back and we could look at some of the original designs, but it’s difficult to tell what exactly it was. But we were looking under a P tube station, and the P tube stations are the ones that have the pipes under the floor, and they had not been moved when they re-carpeted. And so the original carpet was under the P tube station. So they were able to cut a piece out, and it was what’s called woven carpet which they don’t do anymore. But they took it to the carpet people, not Mohawk, Shaw Carpet, it was Shaw Carpet, and they took their current tufted way that they do carpet and analyzed the colors and analyzed the pattern. And by adding an addition yarn into their current method of weaving — of creating carpet they were able to recreate the carpet. And they went through about 15 to 20 different ways that they did it in order to get it with the pattern and the texture that we wanted. And so that was really cool to do that. And when you look at them it’s just remarkable what they’ve done. So the same thing with the wallpaper. We were in there one day, and the finishes guy noticed that they had removed a fire extinguisher off the wall. And behind that fire extinguisher was the original wallpaper. So by going back to the original plans they found the original manufacturer of the wallpaper. They went back to that company which had been purchased. They went back to the purchased company. They actually found the roller in their warehouse, and they were able to use that roller. It had been retooled, so our current recreated wallpaper has a greater definition than what was on the walls, but it’s just remarkable. And so they were able to recreate it after about 15, 20 tries of getting the color and the pattern because it’s a two colored method. And that wallpaper has been recreated in the MOCR. So it’s really cool. And the ceiling tile same thing. They found a piece of ceiling tile in one of the old phone booths in the lobby of 30. And so they were able to go back and get a piece of Armstrong tile. But they had to hand stamp the whole pattern on each of those tiles. It took four different stamps, four different ways to hand stamp. So that’s the level of detail that they’re going to. I mean it will be remarkably — it will look just like it did in 1969.

Host: And the places you’re finding these elements are astounding. You don’t just go to the floor and look at the carpet and be like, all right, let’s match this. You’re finding it in the weirdest places.

Sandra Tetley: Right, right. It’s a little bit of the hand of the Lord to find these little details. But that really will make it great. Because whereas before we were just going to use the same wallpaper and then recreate the carpet from what the flight controllers were telling us. And so this now we have no doubt. It’s going to be just a recreation of the original.

Host: So a lot of it, it seems like the restoration project really is getting everything with the original carpeting, this is what the carpeting was, this is what the wallpaper was. The consoles are a little bit different, Apollo 15 era. But it’s really getting all these different elements together to make sure that history is captured. But you also talked about another part which was you want the screens to show Apollo 11, what they would look like with Apollo 11. So not only are you talking about getting materials, but you’re talking about getting information now from Apollo 11. So where did you go to find that?

Sandra Tetley: So that’s Adam’s forte.

Adam Graves: Well, it’s been a difficult process because we’re really trying to hone in a few different events during descent and landing on the moon, during the EVA, during recovery. Those sorts of things, the video and camera work that was done in the MOCR was interested in the people that were in Mission Control. Which ultimately that’s what we’re trying to get through our project as well is highlight the men that worked in this room. So there’s so much that we’re missing from those time periods because there’s not just a camera locked on the screens, right? So we have to look at video and say, oh, that camera just moved across the screen, let’s pause it and see if we can figure out what that is. And it’s dark or blurry or whatever. And so just a ton of research to try to piece these little pieces of photograph and camera together to, okay, during descent and landing what’s on screen 1, what’s on screen 2, what’s on screen 3, and just piecing all that together. And now we know.

Sandra Tetley: And even the clock. So what was on the clocks have to match on the screens, what was on the consoles.

Adam Graves: Right. And we’re not talking just still imagery of something on a screen that we’re going to be presenting. It’s going to be working.

Sandra Tetley: Moving.

Adam Graves: So there will be a large map on the middle screen, and you’ll see the CM moving across the screen. And it’s timed up with the clocks that are above it with the GET times and things like that. So it’s not just going to be a picture, a still picture. It’s going to be a real living room.

Host: Yeah, you’re not capturing a moment in history. You’re capturing a length of time. And all this data has to synchronize. The clocks have to match where the CM, the command module was at this time.

Adam Graves: That’s exactly right.

Host: Oh, wow.

Adam Graves: And even in the viewing room we have 1960 TVs that we’re retrofitting, and they’ll be playing CBS footage in the viewing room. That’s also timed to landing and EVA and things like that.

Host: Right, and this is actually an important thing. Because when we go back to before the restoration project, what the Apollo Mission Control Center really looked like, I mean there wasn’t really — you had some B roll playing on the screens up front, but really there was nothing on the actual monitors of the consoles, the buttons were not lighting up. It was just left. It was just left there.

Sandra Tetley: Right, there was no audio. We’re going to have audio. So we’ll have everything synced up. So when you walk into the viewing room you’re going to think you’re back on July 20, 1969. That’s our goal.

Host: Oh, that’s wonderful.

Adam Graves: Exactly the sights and sounds that were on that day.

Host: Now some of the things I really loved because I used to give tours of the Apollo Mission Control, that was actually one of my first intern jobs. And then my first like real job when I came on was giving the tour and capturing these historic even artifacts within the room. And there’s some that I always loved to highlight. They had a mirror from the Apollo 13 mission that the crew presented to the flight controllers saying it reflects the true heroes of this mission, really the controllers on the ground working through all different scenarios to rescue the crew.

Sandra Tetley: Right.

Adam Graves: They are coming back. And it’s important to us for the restoration to preserve everything that we can that was in the room through shuttle and Apollo and all this. We say we make new carpet or make new wallpaper. That’s true, that’s a lot of it. But we’ve also preserved in place some of those elements as well that we could. And the consoles are not being repainted. They still show history. There’s still some rubs on them. We’ve preserved them, we have wax and they look nicer but the history is still there. So that’s the goal throughout. And so the plaques you talk about they’ll be back in there. When you look on the wall you can hold up a picture and see a Apollo 11 picture. And on the wall the plaques that should be there are there in their appropriate locations. But down the hallway in another location are the proclamations, and there will be the shuttle plaques and things like that that belong in that room.

Host: Wow. Okay, I’m very excited. I actually can’t wait to step foot in there. And actually that’s a good segue into the next part was you mentioned when you actually walk into the room you’re going to be living this moment through history. What will it look like whenever the room is ready and people can start viewing it? Because, you know, like one of the things that were happening before, as you mentioned Sandra, was people could just walk in and do whatever they want. What’s going to happen after this restoring project?

Sandra Tetley: So the best place to view the Mission Control Center will be from the visitor’s viewing room. So the plan is to have everyone, even employees, to go up the visitor’s lobby and the visitor’s staircase into that alcove that goes into the back of the viewing room. And then when you step into there you will be stepping back into time. And then the seating, we’ll have the best seating because we’re going to have the clocks working, and the summary display screens will be working. So sitting in those seats will give you the best view of everything happening. And when you walk in you’ll hear the chatter from the flight controllers and the command module and the astronauts. And you’ll be hearing all that as we begin to count down. And then when the show starts at some point, like a docent or whatever or just an employee, when the show starts then we’ll begin at the descent and landing, and then we’re going to land and you’ll experience all that. And a very important part that we’re continuing to fight even right now is that during that landing and landing on the moon there was no video at all. The only thing the flight controllers had to look at was what was on the screen, their screens on their consoles, and then what was being shown through the computer where the lander was. So that’s a very important historical element that we’re trying to show is that these men landed on the moon just given this data, even with the alarms going off and all that, they were landing, so you’re going to hear that and you’re going to see that. And then from that after they land we’ll go to the first steps and we’ll walk through the first steps. And then we’re going to do where Nixon called the moon from the White House. And a lot of people don’t even know that that really happened. But he called them after planting the flag and so they’re standing there with the flag. And then we’ll cover when they’re on the Hornet coming back. And one of the cool — tell them about the upside down camera. That’s a great story.

Adam Graves: Oh, yeah. So on the very rightmost screen if you’re sitting in the visitor’s viewing room which is also restored and restored seating and ash trays in the front, you’ll be in history in there as well. So you’ll look and see when the very first video appears in Mission Control after landing, Neil Armstrong is coming down the ladder. And it turns out that that video is upside down. So there’s a little bit of communication here, a little bit of chatter as you’re experiencing this to flip the view, the vision, of the screen upside down or right side up, sorry.

Sandra Tetley: Yeah, it’s very cool. Because you’re watching it and then the flight controllers are going your image is upside down. And so then they flip it right side up. And so we’re going to show that, and then you begin to see it. It clears up a little bit because it goes from one satellite to another. And then it clears up, and then you see him step on the moon. So those little elements like that that people may not remember or may not have experienced, you know, if they were young, those are really cool elements. Because it shows — we’re really trying to focus on the flight controllers and what they did as far as the mission. Not just astronauts which we always hear. And so those are really cool elements that we’ll be able to show in the visitor experience.

Host: Wow. So it’s not only restoring all these elements and making it look and feel like it did in the 60s. Now you’re adding this show really. You get to sit down and experience it. Is it an ever-looping sort of thing? Is that how it’s going to be? Or is it you sit down and press play and live this moment through this moment?

Sandra Tetley: Right, you sit down and press play.

Host: I see.

Sandra Tetley: Yeah, it won’t be going all the time. It will be set to where if you go in with a group you can get it to start. And then it goes through the whole thing until recovery. And then the mission accomplished where they celebrated in the MOCR. And then it will reset back to a time that, you know, people can take pictures, and it will stay at that static state. Then it will recycle. We have a very sophisticated show controller. It’s going to be very cool, yeah.

Host: [Laughs] I want to be one of the first to do it.

Sandra Tetley: And even the lights, the lights are going to change to the way they were. And the quiet sign, the quiet please sign will come on. It’s going to be just like you’re there is what our goal is.

Host: Wow. How did all these elements come together?

Sandra Tetley: Lots of experts.

Host: I was going to say —

Sandra Tetley: Oh, a lot of experts.

Host: Yeah, you must have — I mean this was part of your research then, right?

Adam Graves: Yes, my research and the other teammates’ research and visiting the room over and over and over again and finding this detail and that detail. And discussing it with other experts and discussing it with flight controllers. It’s just a lot of work.

Sandra Tetley: A lot of photos, a lot of video.

Adam Graves: A lot of photos, yeah. It’s so funny when someone shows me a photo now I’m just like, oh yeah, I have seen that one before. Thank you. I haven’t been hit up for a new one lately. It’s been a while since someone said, hey, have you seen this, and I’ve said, no actually, where did that come from?

Host: It’s probably all you dream about anymore, just for how much you think about it it’s just in your dreams now, all these different details. So this was actually a good point you brought up was the visitor’s viewing room seats are going to be restored. That’s actually part of the project. So not only are you going to sit and be able to experience what’s in front of you but exist in a part of history as well —

Sandra Tetley: Yes.

Host: — with the quiet please signs coming up and everything.

Sandra Tetley: Right.

Host: You mentioned other rooms, too. There’s the bat cave which I thought was a super cool name, and then the simulation control room. Are those viewable from the room? How are those being restored and how can you access those?

Adam Graves: Yeah, the sim control room is actually a neat one. We were able to — we discussed among the group, and since we really are creating this live experience in the MOCR itself, we wanted to present more of a preserve in place like exactly what it — artifacts in the sim control room. So the consoles there everything, all the elements, all the components, the monitors, everything are being Apollo era stuff, like the real things that we put back together in their original locations. It’s not lit, it’s the actual artifacts. So everything in there is very unique to that time period. It’s just a little capsule in that room. And you will be able to see that room from the visitor viewing area through the window. I think when we started this project there was a curtain and things like that —

Host: Right, I remember the curtain.

Adam Graves: — in the way so you couldn’t really —

Sandra Tetley: It’s the room behind the curtain.

Host: Right.

Adam Graves: Yeah, it’s the room behind the curtain. So you’ll be able to see, it will be open, lit, and the lighting will be lit so you can see the consoles in there.

Sandra Tetley: And we also are doing a little remembrance, I guess, of the recovery operations control room. So those are the other two windows that are painted out. We’re going to put glass that has imbedded in it photographs of it. When you walk by or when you see it, you can see it also from the viewing room, that you’ll look like you’re looking into the recovery room. Because it was not just the flight controllers by themselves. They each had a big back room. And so by showing off the sim control room and the ROCR that is representative of the back room and all the other people that may not have been at a console but it was all the support people. And so it was important for us to tell those stories as well.

Host: Right, it was bigger than just what you’re seeing in front of you in that room. There was all kinds of support. And that still exists for Mission Control even today. You can come and look at the International Space Station flight control room and, yes, there’s everyone looking at all these different elements, but they have back rooms as well. They still have that support. You’ve still got the simulations in other rooms. So it’s very much still a part of the flight operations culture even today.

Sandra Tetley: Mm-hm.

Adam Graves: Yeah, so the bat cave, also the summary display projection room is the official name —

Sandra Tetley: Right.

Adam Graves: It’s not the fun name.

Host: We can use it.

Adam Graves: Yeah, we’ll go bat cave. There’s a lot of bat jokes we can do there. But, yeah, that room is actually going to be a little bit of a museum. We’re going to move some of the old large artifacts that were in there, cabinets and the Eidophor projectors and things like that that used to be in the room that did all the work. They’re not as elegant as some of the other things that we’re doing. But we have those things. We’re cleaning them, we’re putting them back in place right where they were. So if the time ever came that anyone could ever go back there and look around they would see some of those original elements to the room.

Sandra Tetley: The mirrors are still there, all but one.

Host: Oh.

Adam Graves: The mirrors are still there. Yeah, the projection system that we’re installing will actually use the same methods that the old Eidophors did, where we’re projecting off of those large mirrors onto the screens and backlighting the screens. And those new cameras, new projectors will be in the same location as the old Eidophors and like that. So it’s all going to be set up exactly how it was, just with some new technology back there.

Host: Okay, yeah. So you’re not getting the old style I guess projector, you’re updating it a little bit. But the technique that a lot of the mirrors and capabilities of the bat cave will be preserved.

Adam Graves: That’s exactly right.

Host: Will that be accessible by museum tour or just something you could do here if…?

Sandra Tetley: No, it’s not accessible at this point.

Host: I see.

Sandra Tetley: We kind of ultimately we’d like to make it like an engineering tour to see how it all works because it really was state of the art at the time. And so, but the lights of the projectors are so strong that it presents a safety issue if you go back there when they’re lit. So we haven’t figured that out yet. But ultimately we would like it to be on tour. Because it will have the original Eidophors and the huge equipment racks that supported all the projectors and the slide projector that was the glass and silver slides that would project. So it will be cool, but right now it’s not on tour.

Adam Graves: We’ll have a special tour for your very high level nerds that like that kind of thing.

Host: See, I don’t even consider myself a high level nerd, but I am super interested in this bat cave.

Sandra Tetley: It’s going to be very cool.

Host: Yeah, it looks awesome. I’m excited because it seems like this is all coming together. Now we are recording this now in April. Tell me now what you have done so far to this point and what still needs to be accomplished over these next few months until June. Because it sounds like this is a tight, tight —

Adam Graves: We got a late start unfortunately.

Host: Right.

Adam Graves: It would have been nice to have those full six years.

Host: Yeah.

Sandra Tetley: Right. So, let’s see, we have done — all the wallpaper’s been put up and all the painting has been done. The painting was interesting. They actually uncovered the original column markers that were hand painted so those have been restored. What was original paint has just been cleaned. What was not original has been color matched and painted. The seating is up in Plano where it’s all being restored. And original upholstery will be reused, just cleaned. It was filthy and it’s been remarkably cleaned. And they took us off of technical power in Building 30, and so the entire — all the rooms had to be completely rewired, and that was our longest lead time. And that took almost — well, they’re still finishing up right now so it’s about four months of work. And then we put in over 16,000 feet of land cabling so we could hook everything together. So what’s next is the timing clock screens are now being put in their new frames and so they’ll be put back in. They’re going to clean the summary display screens. Carpeting is probably our next big thing. And that’s going to really make the room — it’s going to change the room. It will really be cool. And then from there when the consoles come back in the first part of June then from there then all of the artifacts and furnishings and everything will begin to be put in. And we’re going to start testing the projector systems in May so that we make sure all that’s working and get all the content going and the clocks and all that. So it will start lighting up in May, so yeah.

Host: Okay. Wow.

Adam Graves: Some of that projection is being tested right now, just not in place.

Host: So, once everything does come into place I’m imagining you’re taking me back to this moment in July of 1969. The room itself, 1969 was a different time. I’m imagining you said ash trays in the viewing room. I’m imaging ash trays on the console, papers scattered all over. Are those all coming back, too?

Sandra Tetley: Yes, everything.

Host: Oh, that’s awesome.

Sandra Tetley: I’m collecting the old black SKILCRAFT cross binders. I’m collecting those and those will have papers put in them. They’re recreating maps that will be put on there. We’re getting old coats and jackets that used to hang in the little coat racks.

Adam Graves: Yeah, we’ve got a number of donated items that we’re making copies of to pile on the desk. You look at the photos and videos of the room and it’s just a big messy pile of papers for the most part. But interestingly enough we know what a lot of those papers are. So we’re getting those and putting them back. And yeah, the ash trays, and actually we’re doing some vacuuming under the floor today, and they’re like there’s cigarette butts and there’s a whole cigarette pack and these things that we can use to put in place so it’s really fun.

Sandra Tetley: And our contractor that’s doing the furnishings is using eBay a lot. I mean they’re being very successful on eBay as far as cups and lighters. And they even found the rocket coffee pot that was new in the box and so we have that now. So that’s great technology that we’re able to utilize in getting all of these things that will be on the consoles.

Adam Graves: Yeah, it’s really amazing because 10 or 15 years ago if you were doing this restoration project it would be a real hassle to try to come up with some of these items. And thank goodness for eBay now and things have changed.

Host: Yeah, just easy access to find, you know, “historic cup still in the box,” boom, there it is.

Sandra Tetley: Right. [Laughs]

Host: Internet is fantastic. I just want to take this moment actually to thank you for coming on the podcast right now because it sounds like you’re right in the middle of a ton of work, and yet you have decided that it is worth an hour to spend here talking about it. But I really appreciate, A, everything you’re doing for the restoration project but, B, your time today. So that’s actually I think a perfect place to end. Thank you so much for coming on.

Sandra Tetley: Thank you for having us.

Adam Graves: Thank you so much.

Host: And describing this project in detail. I think it really captures just the amount of work and effort and research especially that goes into capturing this moment of history. It’s going to be spectacular when it’s open to the public and we can’t wait.

Sandra Tetley: Yeah, I can’t wait for you to see it and hear what you think.

Host: Thank you. I’m going to be the first one there.

Sandra Tetley: Good.

[ Music ]

Pat Ryan: Near the end of Gary’s talk with Sandra Tetley and Adam, Graves, they discussed how visitors will be able to go the viewing room of the restored Apollo Mission Control Center and go back in time to see and hear what happened out on that main floor during the historic events of Apollo 11. It’s a real nice immersive experience. They didn’t talk much about where that audio came from or how it’s been prepared to be part of this show. But I’m going to right now with Ben Feist. He’s a web developer by day with his hands in a number of other online and media projects including cleaning up the quality of the Apollo 11 Mission Control Center audio.

Ben, how does a web developer in Canada get involved processing audio from space missions from 50 years ago?

Ben Feist: That’s a very good question that I ask myself very often. I think it’s really because I’m interested in the history of Apollo. And I spent a lot of time from about 2009 until now helping to bring the Apollo missions back to life through real time web experiences. And I’ve built a website called Apollo17.org which replays that mission in real time from beginning to end, all 302 hours of it.

Pat Ryan: Wow.

Ben Feist: And that have many different branches coming off it, one of which is eventually finding myself on the team that’s helping to restore the Apollo Mission Control room.

Pat Ryan: Before we get to that, tell me about how you got involved in audio processing at all, your technical background that got you the skills to do this work.

Ben Feist: Well, I’m by no means an audio engineer. I — it was out of necessity I basically got ahold of the Apollo 11 30 track audio which was painstakingly restored and digitized by a team out of UT Dallas.

Pat Ryan: Which we’ve heard about before around here.

Ben Feist: Yeah, yeah, so I’m sure in great detail. So their work was just phenomenal. And I managed to get my hands on a copy of this audio. And I was very disappointed to hear that it actually had many audio defects in it. And these defects were fine I think for the research that was being done using that audio. You can still tell what everybody was saying, everything’s intelligible. But in terms of playing it back for public consumption it suffered a little bit from having something called wow and flutter which is a technical term which means speed variations happening almost like the sound of an opera singer holding a note. With the vibrato going up and down at about that frequency was pervasive through all of the audio so the purpose of — go ahead.

Pat Ryan: Let me ask did you did you realize that it had that just from listening to it? Was your ear tuned well enough to tell that?

Ben Feist: Yes. I think anybody who listened to it would tell you there was something wrong. It sounded like everybody was worried as they were talking.

Pat Ryan: Like their voice wavering because they weren’t sure what they were going to ask.

Ben Feist: That’s right. Yeah, something like that. So after knowing about this audio that it existed since 2014 and finally getting my hands on it in late 2017, I was very disappointed and had to come up with a technical way to solve this problem. And my background is in software engineering. So I just approached it like a programming problem and sort of Googled my way through what’s out there that can solve these kinds of problems. And there isn’t a lot. And I began a journey of trying to figure out a way to technically solve it which I’m happy to tell you about if you’re interested.

Pat Ryan: Yes. And first before I get there what was it that made you aware that this stuff existed in the first place? I think you said in 2014 you knew about it, but how did that happen?

Ben Feist: Well, when I was doing the restoration work on Apollo 17 I had a deep down fear that there might be some other person out there doing the same thing. So I began writing a series of blog posts on a personal website that just told people that, hey, I’m doing this step by step, and then each step took several years. And I was contacted by the people — by Dr. Hansen and by Doug Oard, somebody who works in the University of Maryland, a professor there, who approached me basically saying, hey, how have you solved the time problem of when did these analog tapes — playing them back at the right speed when did things occur on these tapes. And they started an email thread with me way back in 2014.

Pat Ryan: Right.

Ben Feist: And they explained about this 30 track audio that they were attempting at that point. I don’t think they’d even started to digitize. And so as soon as I found out it existed I, of course, wanted a copy.

Pat Ryan: Okay. Then you were going to tell me about how you corrected or fixed if you will the wow and flutter that you were hearing starting with the Apollo 11 tapes.

Ben Feist: Yes, the Apollo 11 tapes were what this was all done on. Essentially each of the tapes is a 30 track tape. And track 1 of each of these tapes has a time code on it in a format called an IRIG. So an IRIG time code signal sounds like dial up modem sounds. It’s just sort of this audio buzzing noise that you can’t make heads or tails of.

Pat Ryan: Right.

Ben Feist: But I wanted to know what time things occurred, so I needed to figure out how to decode this IRIG time code in a digital format. So basically process that sound through a piece of software that I could write that would then tell me what time it was at every give point in the tape. So I wrote that software. The IRIG time — I always say ear-RIG because I only ever read it, but everybody else I’ve ever heard say it says I-RIG

Pat Ryan: IRIG, yeah.

Ben Feist: So I have to try to remember that. So I found the spec on what that time code consists of. And it’s actually quite a primitive signal that a Joe Blow like me could actually figure out and understand. It’s not a very complicated multiplex signal of any sort. It has very basic timing information in it. So I wrote a piece of software that did that. And it pulled that information out. And it told me that the tapes were being played at the wrong speed. They varied almost by 45 minutes over a 16 hour tape. And this is a natural problem to have when you’re dealing with analog equipment. Especially when there’s only one machine in the world that can play these tapes back how do you determine what speed it was supposed to be playing back at?

Pat Ryan: And you’re able to tell that there was a discrepancy because the IRIG time code wasn’t matching up with how long it took you to actually play the tape out?

Ben Feist: That’s correct. So because these tape recordings had been turned digital by digitizing them, the digital audio files definitely had a known length. And the time that was coming out was running off a very different speed than the actual digital files. And the real breakthrough was understanding that the signal itself of the IRIG time code contains a carrier wave. This carrier wave is a tone that’s supposed to always be playing at 1 kilohertz. And it’s a simple sine wave tone. And you could look at the flutter and wow in the tape to see that that waivered above and below 1 kilohertz very regularly, almost three times a second, was the flutter. And the wow was a very long time period shift in speed that I was just describing that made the time code be way off.

Pat Ryan: And we think that the cause of this is the mechanical playback when the tapes were digitized?

Ben Feist: Well, this is me sitting in my basement in Canada trying to imagine what could have caused this. I don’t know anything about tape machines or what it takes to make them work properly. But I was imagining some sort of fly wheel balance problem that could have been spinning and causing a wobble or a warble to be introduced. And perhaps older motors or parts of the machine that weren’t working the way they originally did that made it play back at a long period different rate.

Pat Ryan: And you were attempting software to compensate for whatever was causing this?

Ben Feist: Yeah, luckily I didn’t have to become a mechanical engineer to try to fix the machine. The digitization was already finished. So I had to make do with what was there. And this carrier wave became the key to the entire thing. What I could do was write software with another gentleman who I found who had written very similar software, and he lives in Europe. And he basically said if we can figure out each sample of this time code, if we figure out how far off that carrier is from one kilohertz, that we can create a fingerprint that is a corrective fingerprint for the speed variation, the flutter and the wow for this entire tape. So sample by sample you go through each. And for people who don’t know what a sample is, it’s essentially a digital frame of information that if you glue these together become sound. So each frame of information of the sounds we could check what the actual frequency was of the carrier and say that this sample needs to be sped up or slowed down by this amount —

Pat Ryan: Right.

Ben Feist: — and we did that processing each of the 11,000 hours of audio. So we —

Pat Ryan: In pieces that were how long?

Ben Feist: Sixteen hours in length. Each track of each tape is 16 hours in length.

Pat Ryan: And when you were examining them were you examining them at say one second’s worth or one half second’s worth or what in order to make that judgment?

Ben Feist: No, at 8,000 frames per second, at 8,000 samples per second we could look at that carrier and tell it to adjust.

Pat Ryan: And you were at each one of those 8,000 frames?

Ben Feist: That’s right. This is not something that can be done manually. You set your computer to work and you go have a coffee, and you stare impatiently and wait for the result. And then open up the result and have a look. And lo and behold the carrier wave was flat at 1 kilohertz. And if you did an analysis of the time code we reduced that variance to less than two seconds over 16 hours of speed variance.

Pat Ryan: Terrific. My goodness. And then when you played it back did it make a big difference in your ear to hear it?

Ben Feist: A huge difference. It essentially turned that in from something that sounded very far away and in the distance to something that sounds like it was played much more recently. Everybody’s tone of voice is their actual tone of voice because we know this is the exact speed that the tape was recorded at based on the very accurate time code that was being laid on track 1. So the important thing to think of here is that track 1 carrier is what gave us the fingerprint. But we could write the corrective resampling to every adjacent track on each 30 track. So even if an adjacent track was silent or had huge gaps of nobody is talking in it, even the part that was gap is re-speeded and corrected and has flutter removed from it.

Pat Ryan: So that the finished product, all 30 tracks, still have their integrity in terms of their time relationship to one another.

Ben Feist: That’s correct.

Pat Ryan: Wow, that’s neat. And for anybody who may have heard some of that in our earlier podcasts, we used that corrected version. That’s what you were hearing, and it really did sound they were people talking today.

Ben Feist: Yeah. And I think if the machine was new and it was 1970, say, and we were playing those tapes back that’s what the machine would have played back for us to digitize had digitization existed in 1970.

Pat Ryan: Right. Now, from the point of having done that and you’ve got this great sounding audio, how did you then get connected to the NASA work in restoring the 1969 era Mission Control Center here, the Apollo Mission Control Center?

Ben Feist: Well, that’s an entirely unrelated and crazy story —

Pat Ryan: Okay.

Ben Feist: — of myself getting a job at NASA. I now work at Johnson Space Center in Houston. And that is because of the work I did on Apollo 17, eventually slowly leading to me being given an opportunity there. So I’m very excited about that, and it’s something quite new. But Gerry Griffin who was one of the flight directors on Apollo 11, I got to know him, and he said that if you’re going to Johnson Space Center there’s somebody you should meet, and that somebody is Sandra Tetley. So I didn’t know who Sandra was or what she was working on and I met her. And I told her about this work that I was doing. And she, oh my goodness, can you please help us to make the MOCR restoration as historically accurate as we possibly can. And I said of course I would. That sounds like a dream.

Pat Ryan: And tell me about your role in that. What have you been doing?

Ben Feist: This is again related to the 30 track. I was part of the team that made the recent film called Apollo 11. And that film used this restored 30 track audio. A gentleman named Stephen Slater from the UK used this audio to add sound to the previously silent 16 millimeter footage that was shot in Mission Control. So we’d be able to figure out who somebody was and roughly when the silent footage was shot in Mission Control. And they can say, hey, wait a minute that’s the flight dynamics officer and it’s about seven hours after launch. And because I had corrected exactly the speed of each of the tapes and decoded the time code from the IRIG channel, it’s sort of a way finding capability to go to. Give me the flight dynamics channel at this time, and he painstakingly lip synched up the audio that was in that 30 track recording with the silent footage. And the moviegoers were basically going how come I’ve never seen any of this before? Well, it didn’t exist before this.

Pat Ryan: There was no before.

Ben Feist: That’s right. So when I told Sandra about that work on the 16 millimeter film that now had audio to it, and the fact that all the 16 millimeter footage from Apollo 11 had been rescanned for the film, and we were able to then scrub through the 16 mill film and determine what happened in the mission. What was on the desks, what was on the screens, what were people saying at every step of the mission to try to help make sure that MOCR was exactly being restored to what it looked like.

Pat Ryan: Now, you’ve posted that restored audio out in a public website, too, where anybody can see it without having to come to Houston.

Ben Feist: Yes, not quite yet. I’ve not quite finished this website. But it’s going to be launched in June. And it’s essentially the same thing that I did for Apollo 17, a real time recreation of the mission, but it’s the real time recreation of all of Apollo 11. And during the Apollo 11 anniversary the general public will be able to go this website, open it up and drop in on history and see what was going on in the mission right now. What photos were being taken by the crew, what stage of the mission are they in, are they walking on the surface or during a sleep period? It’s all going to be real time. And it’s essentially this direct way to experience the mission. And part of that this time, what Apollo 17 didn’t have, I have all the 11,000 hours of Mission Control audio now synchronized to exact mission time that you’ll be able to open up a panel and click on any position in Mission Control and hear what that person was both saying to the people in their support rooms and what were they listening to from other controllers to really unravel how did Mission Control operate during Apollo 11.

[ Music ]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. I really hope you enjoyed both of these conversations about restoring the Apollo Mission Control Center. Very exciting stuff. And actually we’re about to open it up to the public here very soon later this month. You can check out our Apollo page. Houston We Have a Podcast has a page dedicated to the 50th Anniversary of Apollo. This episode will be one of them. But we’ve also gone into depth especially with that talk with Ben Feist. We went into a deep couple of episodes called “The Heroes Behind the Heroes” of the actual process of recovering that audio. I hope you check those out on that Apollo page. Otherwise you can see what else is going on here at the Johnson Space Center at nasa.gov/johnson. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, the Johnson Space Center. You can see some of the photos once they actually open the exhibit of the rollout of what you can actually check out here at the Johnson Space Center of the Apollo Mission Control Center. If you have any questions for us use the #askNASA on your favorite platform. Submit your ideas. Make sure to mention Houston We Have a Podcast. We might bring it right here on the show. So this podcast was recorded on April 3, 2019. Thanks to Norah Moran, Alex Perryman, Greg Wiseman and Pat Ryan. Thanks again to Mrs. Sandra Tetley, Dr. Adam Graves and Mr. Ben Feist for coming on the show. We’ll be back next week.