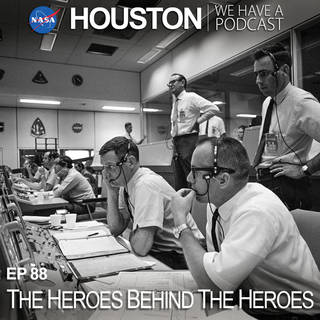

“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

Episode 88 is a special edition of the podcast, the voices of the people who saved a piece of American spaceflight history tell the tale of reviving an obsolete piece of audio equipment that was vital to digitizing the voice recordings of the Apollo 11 flight controllers in Houston.

If you’re interested in hearing more of this historic audio from the Apollo 11 Mission Control Center check out the Explore Apollo website. For more of our Apollo Podcasts check out the “Houston We Have a Podcast: Apollo 50th Anniversary” webpage!

Transcript

Pat Ryan (Host): Houston We Have a Podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 88: The Heroes Behind the Heroes. I’m Pat Ryan, your host for a special edition of the podcast. Ordinarily, we talk to NASA scientists, and engineers, and astronauts, and others about the cool stuff they’re doing right now, but this time, we’re going to veer off that course a bit, and let me tell you why. Several months ago, I was in a regular meeting where we talk about stories the NASA Public Affairs Office in Houston could or should do, and, well, you know how meetings can get. I suddenly snapped to a story that one of my coworkers was pitching. It had to do with a university professor from Dallas and some of his students who had worked with voice recordings of the flight control team in Houston during the first Moon landing, and they had to make use of an enormous piece of ancient audio equipment that has lived in one of the rooms here in our production facilities for years. It’s a big, green monster that I have never, ever seen in operation, even one time. Well, the more he told of the story, the more it struck me as a terrific mystery. Well, not exactly a whodunit, but maybe a how they do that, or they did what? Well, you’ll see as we go along. So I talked to him more after the meeting, and we agreed to try to produce this story for the podcast. His name is Greg Wiseman. He’s one of the audio engineers in the Media Production Services Department here at JSC. And you’ll hear him as part of the ensemble of voices that we’re about to unleash on you. What’s coming up now is the story we flesh out, starting with Greg’s recollection, plus podcast interviews I did with 8 people who lived the story, and narration by me as a means to tie all the pieces together. So to invoke the spirit of Gary, here we go with the story of the rescue of the audio of the Apollo 11 Mission Control Center.

[ Music ]

Host: A regular by-product of the work done by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration is the creation of pieces of history. It’s a natural occurrence when your job description is to do things that have never been done before. I’ll wager that you’ve heard some of the highlights before.

Neil Armstrong: Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.

Charlie Duke (Capcom): Roger Tranquility, we copy on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.

Host: And this bit, which came just hours later.

Neil Armstrong: That’s one small step for man. One giant leap for mankind.

Host: But it’s a lot less likely that you’ve heard this bit of history before.

Flight Director: T2 stay/no stay, all flight controllers. T2 stay/no stay. RETRO?

RETRO: Stay.

Flight Director:FDO?

FDO: Stay.

Flight Director:Guidance?

Guidance: Stay.

Flight Director:CONTROL?

CONTROL: Stay.

Flight Director:Telcom?

Telcom: Stay.

[ Unintelligible ]

Flight Director:EECOM?

EECOM: Stay.

Flight Director:Surgeon?

Surgeon: Stay.

Flight Director: Capcom we’re stay for T2.

Host: Or this one.

Jack Schmitt: Excuse me Fred.

Fred Haise: Yeah.

Jack Schmitt: This is Jack Schmitt

Fred Haise: Yeah.

Jack Schmitt: Say, is John around?

Fred Haise: John who?

Jack Schmitt: John Young?

Fred Haise: No, he’s not here.

Jack Schmitt: I was just wondering. I’d like to get a in flight, somebody who’s looked at it before opinion so people are–

Host: Those first 2 clips came from Apollo 11, the mission that put the first human beings on the surface of the Moon. The second 2 clips also came from Apollo 11, and there’s a story behind how we have them available for you to hear. It’s the story of how a small group of dedicated scientists and engineers saved part of America’s spaceflight history while they were trying to build machines that could better understand us when we talk.

Like most good stories, this one does not go in a straight line from Point A to Point B. That would be the shortest distance between the 2 points, but not necessarily the most interesting trip. This narrative runs into unexpected developments. And the way the characters in the story deal with those roadblocks is as much a part of the lesson as is their achievement of their original goal. The story involves elements of sophisticated analytics and engineering and other stuff that I find interesting as hell, even though I can’t do the math on my own. It also has important and exciting world history. And near the end, we’ll tell you how you can access that history on your own. The story has 2 beginnings on unrelated tracks — Points A and B, I guess — which merge with one another in 2013 at Point C and then move forward.

[ Music ]

One track begins in Plainfield, New Jersey near the dawn of the Space Age with the birth of a smart and curious boy who would grow up to earn a bachelor’s degree with highest honors from Rutgers and then a master’s with highest honors and a doctorate from Georgia Tech, all in electrical engineering. His name is John Hansen, and he studied digital signal processing and speech processing and communications and biomedical engineering, and he wrote a dissertation entitled [clears throat] “Analysis and Compensation of Stressed and Noisy Speech with Application to Robust Automatic Recognition.” All of this is to say that back in the 1980’s, when none of us carried portable phones that understood what we said to them and followed our instructions, John Hansen was helping develop machines that could understand human speech. It was a focus of his academic research, which continued at Duke, and Colorado, and, since 2005, at the University of Texas at Dallas, where he’s now the Associate Dean for Research at UTD’s Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science. He’s also the university Distinguished Chair in Telecommunications Engineering and the director and founder of the Center for Robust Speech Systems, among other things. When it comes to speech recognition technology, he knows his stuff.

The other track stretches back, as they sometimes say, from time immemorial [echo]. Even in caveman times, the human residents of Planet Earth had a curiosity about the lights in the nighttime sky. Maybe the other animals had it too. But anyway, humans have paid attention to the things in the skies, and made use of them, and wondered about them. The Ask an Astronomer website at Cornell University cites early civilizations that use the bodies that moved across their skies to keep track of time, to orient their cities. They named the stars and plotted their positions. By the Middle Ages, they’d proven that the Sun is the center of our solar system and described the orbits of the planets. And they used telescopes to get a close look at the planets and the Moon, Earth’s largest natural satellite. The fact that the Moon has been on our minds is reflected in art through the ages. Just go online and search “Moon in art.” You’ll see what I mean. It’s also in music — “Fly Me to the Moon,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Moondance,” “Moon River,” “Blue Moon,” “Pink Moon,” “Dark Side of the Moon.” It was also the subject of A Trip to the Moon. It’s one of the earliest science fiction films. You know the one — the, with the image of the bullet-shape rocket ship stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye. In the latter half of the 20th century, the idea of sending people to the Moon became a goal during the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union. That started over the nuclear arms race and the development of ballistic missile technology in the service of national defense. And that led to launching artificial satellites to Earth orbit, and then to launching probes out of Earth orbit, and then, well, then it was let’s launch people to the Moon. And here we are back in Texas in Houston at Rice University with President John Kennedy. He had proposed to Congress in mid 1961 that the United States should establish the Moon landing as a goal. And that led to NASA’s creation of Project Apollo and, with it, the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston. When the president came to Houston to visit the construction site in September of 1962, he gave a speech at Rice University that was designed to drum up popular support for the American space program. Here’s an extended cut.

President John Kennedy: Surely, the opening vistas of space promise high costs and hardships as well as high reward. So it is not surprising that some would have us stay where we are a little longer to rest, to wait. But this city of Houston, this state of Texas, this country of the United States was not built by those who waited, and rested, and wished to look behind them.

[ Applause ]

This country was conquered by those who moved forward, and so will space. William Bradford, speaking in 1630 of the founding of the Plymouth Bay Colony, said that all great and honorable actions are accompanied with great difficulties, and both must be enterprised and overcome with answerable courage. If this capsule history of our progress teaches us anything, it is that man, in his quest for knowledge and progress, is determined and cannot be deterred. The exploration of space will go ahead, whether we join in it or not, and it is one of the great adventures of all time. And no nation which expects to be the leader of other nations can expect to stay behind in this race for space. Those who came before us made certain that this country rode the first waves of the Industrial Revolution, the first waves of modern invention, and the first wave of nuclear power. And this generation does not intend to founder in the backwash of the coming age of space. We mean to be a part of it. We mean to lead it.

[ Applause ]

For the eyes of the world now look into space, to the Moon and to the planets beyond. And we have vowed that we shall not see it governed by a hostile flag of conquest, but by a banner of freedom and peace. We have vowed that we shall not see space filled with weapons of mass destruction, but with instruments of knowledge and understanding. Yet, the vows of this nation can only be fulfilled if we in this nation are first. And therefore, we intend to be first.

[ Applause ]

In short, our leadership in science and industry, our hopes for peace and security, our obligations to ourselves as well as others all require us to make this effort, to solve these mysteries, to solve them for the good of all men, and to become the world’s leading space-faring nation. We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained and new rights to be won. And they must be won and used for the progress of all peace. For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of preeminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new, terrifying theater of war. I do not say that we should or will go unprotected against the hostile misuse of space any more than we go unprotected against the hostile use of land or sea, but I do say that space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours. There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind. And its opportunity for peaceful cooperation may never come again. But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas? We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills. Because that challenge is one that we’re willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.

[ Applause ]

Host: The president’s stated goal in September 1962 was to put a man on the Moon by the end of the decade, which was just 7 years down the road at the time. NASA and its commercial partners got busy, designing and building spacecraft, testing and flying, and testing and flying some more, drawing up detailed plans for space missions and Moon missions, and developing the architecture and the hardware for the systems on the ground that would support the flights to Earth orbit and then to the Moon.

[ Music ]

Christopher Kraft was one of the first few dozen engineers hired to get the Space Task Group going when NASA was created in 1958. He was assigned to work in flight operations for Project Mercury at a time when no one had flown in space yet. Kraft and his colleagues had to figure out how to coordinate the ground support, the spacecraft tracking, the communications networks, the flight plans and procedures, the timelines, everything. And Kraft decided that the astronaut in a spacecraft shouldn’t be responsible for coordinating all the parts of the spaceflight during the spaceflight. He’s credited with coming up with the concept of the mission control center, the location where engineers with expertise in all the systems that would be needed during a flight could keep an eye on the latest telemetry data for their area of responsibility. And all of them would work in concert to move the mission toward its goal, and they would do that under the leadership of the flight director. Chris Kraft served as NASA’s first flight director, call sign RED FLIGHT, and he was key to inventing the mission planning and control processes that NASA’s been using ever since. Today, the building that houses these flight control rooms in Houston is named the Christopher C. Kraft Jr. Mission Control Center. The dozen or more operators who are on duty during any shift in the control room are plugged in to a voice communication system that has many individually selectable voice channels, which are referred to as loops. This system allows the flight director and each member of the team to talk to one another right there in the room without having to get up from their desk or shout across the room. It also allows each member of the team to communicate with their own support staff, who are located off the main floor in what are referred to as the back rooms. They can also listen to the conversation when the astronauts in space talk to the capsule communicator, called the Capcom, who sits right next to the flight director and is the sole conduit to relaying information back and forth. That conversation happens on a loop called Air to Ground or Space to Ground. Well, let me give you an example: a little slice of life from mission control, Houston, during the Apollo 11 mission.

Voice 1:Hey Telcom?

Voice 2: Telcom Inco.

Voice 1:If you look on page 3-55 A of your flight plan, you’ll see that that at 85 hours—

[ Overlapping Voices 1, 2, 3, 4 etc. ]

Host: Well, you can hear there are a lot of voice loops on the system, and any or all of them could have voice traffic going at any time. What you can probably also figure out, when you think about it, is that an organization like NASA that is famous for its attention to detail, and for striving to have backups to every plan and backups to the backups, just in case, and which tries not to leave any stone unturned over, NASA made the decision way back in the day that the traffic on all these voice loops needed to be recorded. So they needed people to tend to the recorders and the playback machines.

Larry Vrooman: My name is Larry Vrooman. I started working with Ford Aerospace the first week of January 1979. And the recorder, they actually made me, as a technician, responsible for its service and maintenance, that the single playback machine and both recorders were my responsibility until they were retired in 1982.

Host: Now, the machines you’re referring there, to there, the recorders and playback machines, help me understand what they were, what they were designed to do, and, if you know, why they decided they needed those things.

Larry Vrooman: I think they may be unique in that they were contracted, and designed, and manufactured specifically for Ford Aerospace — i.e. NASA. But they were 30-track machines. And at the time, that was a large or intense compaction of channels and probably was the max available at the time in 1961. They were logging recorders, audio logging recorders. They were also, similar models were also used by police departments to record phone lines and their various phone calls. That’s what I, that was my understanding is that they were normally used for phone call recording.

Host: And in the case of NASA, they were recording the voice activity in the Mission Control Center?

Larry Vrooman: Not just the Mission Control Center.

Host: Oh, where else?

Larry Vrooman: A lot of the audio channels, we called them loops. The way they set up the audio system in the building, we called them loops, and each loop could be internal, or external, or domestic, or international based upon its function. And as an example, we had a lot of issues with feedback sometimes or oscillations and funny noises in the system, and it was a constant battle to keep that in control because the, some of those channels went, some of those loops went worldwide.

Host: And the loops we’re talking about, these are voice communication channels–

Larry Vrooman: It’s a lot like a telephone line, but it’s local, and domestic, and international. We had 1 playback machine, which is the one you’ve seen. And then, there was, in effect, 4 recorders. There were 2 racks. Each rack had 2 tape decks in them so they could hand over to each other and, therefore, run 24 hours a day. There were 2 racks. Each machine would, basically, was a backup for the other. If there was a major failure in 1 machine, you just switched to the other machine. It had 2 decks you could continue to run and meet all your requirements. The — and in fact, we had 1 failure that caused us a few days or weeks of downtime on 1 machine. And it’s a good thing that the other machine ran fine during that time. The tapes that I myself handled in recording, we would put them in a rack at the completion of every day, and mark them, and keep them for a year or 2 or so. As long as we were still getting requests from the various flight controllers or whoever needed it, we would need to keep the tapes there, and we would play back and make secondary recordings for them, little snippets here and there. They were used for various purposes.

Host: Like, purposes like what?

Larry Vrooman: Well, an astronaut might want to review an experiment that he did, and he might have some audio that he did down to the ground with scientists or whoever. And he might want to review that to create a transcript or something like that. It just, multiple things. I’ve had lots of — I’ll give you a story.

Host: Yeah.

Larry Vrooman: I had a Secret Service agent come in one day wanting some audio. I don’t even remember what he wanted. But at the end of making the tape, he’s standing there, and he goes, “How do I pay for this?” And I said, “Well, you pay taxes?” He said, “Yeah.” And I said, “It’s paid for.” [laughter]

Host: Good, so–

Larry Vrooman: We had requests from, you know, everywhere for various purposes, and NASA’s an open agency. Anybody asks, we try to provide.

Host: So there were tapes of the conversations of the team of flight controllers who oversaw the successful first landing of man on the Moon. Those might really be interesting for historians or for people who do research in speech processing and language technology.

John Hansen: I do research primarily in speech processing and language technology.

Host: People like John Hansen.

[ Music ]

John Hansen: My name is John Hansen, and my title — I serve as Associate Dean for Research as well as a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Host: And a lot of your work, I take it, is in research. What are your research areas of interest?

John Hansen: So I do research primarily in speech processing and language technology. So that involves looking at audio analysis, extracting information out of those audio streams. That would include speaker recognition, speech recognition, language identification. We also work on applications that might help people that have hearing loss. And perhaps extracting knowledge from audio that might help in the educational space.

Host: That’s hard for me to even follow, the, just the range of things you’re talking about there. Are you creating a new area of [laughs] academic research?

John Hansen: No. No, I, the reason why it sounds like it’s such broad or wide is because the field has evolved over many years. So I’ve been a professor for 28 years, and if you were to go back, you know, into the 1980’s, 1990’s, the main emphasis or focus there, like for speech recognition, was actually small vocabulary — small, handheld devices or voice control. Maybe 10, 20 words or 100 words at most. People were always dreaming and trying to do larger vocabulary speech recognition, but the computing infrastructure was not available at the time. And also, the algorithms were not very mature. And so as time goes on, problems evolve and become different. And I would say, certainly, over the last 10 to 20 years, computing infrastructure has greatly changed the field of speech processing and language technology. And so now, there are new, emerging problems that people weren’t trying to solve 20 years ago, but are actually introducing and helping society in a really nice way.

Host: As I’ve been looking at the story of these tapes, I ran into some stuff that said you got started — the beginning of the story has to do with you trying to find recordings of conversations that involved many, many people. I’ve also seen where it looked like this evolved out of you trying to find examples of groups solving problems. Is either of those really where this story starts?

John Hansen: Yeah. Actually — it’s actually correct, yeah. What, one of the things we looked for is when you look at speech technology, as an engineer, you, you’re wanting to solve maybe some signal processing work, maybe developing language models or understanding how people pronounce words and so forth. But that’s actually kind of like laying bricks, you know. If you’re building a wall or building a house, you can lay that foundation. But what you do after you have that, you know, there’s other people, other things that you might want to do. And so people, for example, in a society, maybe in education, maybe in psychology, are interested in seeing, well, if you could identify or recognize the text of what someone says, how do you interpret how they interact with other people? What do they actually mean when they said these things? And so probably the examples one could look at in, you know, over the last maybe 15 or 20 years might be looking at natural disasters or areas where major security issues. If you look, for example, at 9/11, okay, you might say, all right, well, when an event like this happens maybe in New York City or Washington, D.C. and so forth, how do people actually work collaboratively together? They probably weren’t working together before an event happened. And the instant it does happen, how do people actually connect and understand the chain of command? Who’s responsible for making which decisions? You can also look for natural disasters — Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Rita, for example, here in the Gulf Coast areas. How do people actually, you know, work collaboratively in these modes?

Host: How does a random group of individuals suddenly turn into a group?

John Hansen: Yeah, that’s true. And so, you know, the field of speech and language technology, most, you know, if you look at all the work that’s been done in the field of speech technology, the vast majority, over the last 50 years, is focused on the telephone. But the telephone has always been point to point — one person talking to another person over a handset. And today, when we look at smartphone technologies, it’s much more likely that you would have group discussions. You’re going to have more than 1, more than 2 people kind of working or interacting together. And so the problem in the field of speech and language technology is that there really are no corpora available that look at group dynamics and group interaction. And so when we approached the National Science Foundation, we said we really wanted to kind of come up with research that would advance multi-speaker analyses to try and understand how people work collaboratively together.

Host: And the National Science Foundation was interested. Tatiana Korelsky is the program director of the division that focuses on things like human speech technologies, speech analysis, and speech synthesis. And she reviewed Hansen’s proposal and request for funding.

Tatiana Korelsky: So the proposal that he submitted was, in a sense, very unique because it was meant to use the integration of existing and slightly beyond the state-of-the-art speech technologies, such as diarization and automatic speech recognition, to process very particular, unique data and data which was not trivial. It was very noisy, very multichannel, very multi-speaker. So it was a very, very difficult type of data to process by speech technology. So in that respect and also, an additional, of course, that wasn’t just any corpus. It was the corpus of Apollo tapes, which, in what we call broader impact, was very important because it was very important corpus, which is like our legacy of space program and, in general, a great American achievement. That’s why it was, like, on many, in many aspects, this proposal was unique and very interesting.

Host: That’s right. Hansen proposed doing this research using the audio recorded in mission control, Houston, during the first landing of men on the Moon in July 1969. But why use Apollo 11?

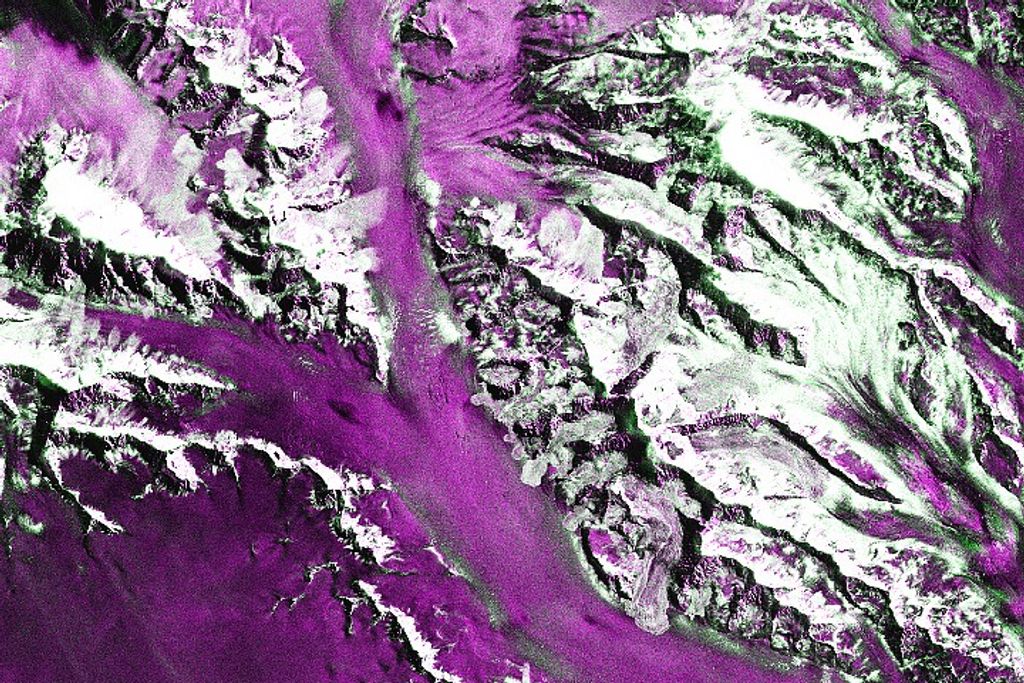

John Hansen: But we couldn’t go to 9/11, let’s say, New York City. You couldn’t go to, like, you know, Hurricane Katrina events and things like this because many of the audio that we could get access to could potentially not be released. In addition to that, none of them were synchronized, so it’s very hard to understand who was doing what and at what time if you don’t have a common time frame. And so those challenges actually NASA solved for us because when we went back, we started doing some homework in looking at Apollo. And we saw, well, lo and behold, NASA recorded all this with timecode. That was the big plus.

Host: How did you become aware that that had even happened? If you had gone to the National Science Foundation and were looking for help but didn’t know where there was, you know, what turns out to be a recording of many people talking all over each other all at the same time, how did you know that that was even there?

John Hansen: We knew that NASA recorded the audio. A lot of the Air to Ground, called Capcom, that’s been released. And so at least that communication we knew was there. However, most of the audio that involved Mission Control, a lot of the back room discussions, support staff that were providing support to Mission Control, most of that audio had never really been released. And we thought, well, this actually would be an interesting space to look at. You know, the average, you know, K-12 type student pretty much knows hopefully most of the astronauts, at least the 12 Moon walkers. But most do not know who was working behind the scenes.

Host: Did you know that those conversations had been recorded?

John Hansen: Well, one of the things that, growing up — and I was a little kid when we walked on the Moon–

Host: So was I.

John Hansen: Yeah, yeah. And for me, the thing I always remembered in looking at every picture or any video played from Mission Control, there was always, you know, a NASA scientist, engineer, specialist — white shirt, little black tie, and a headset. The headset was always on. I could always see that. And so being a speech and audio type person, my feeling was if anyone has an audio set, that means that audio’s got to be recorded somewhere. At least, I would always hope that. And we were pretty fortunate that NASA still had all of these recordings and all of the tapes.

Host: Tell, okay, so you, it was your hunch that NASA had recordings of all these conversations?

John Hansen: Yeah, but we were a little naive, and one of the reasons is because when we wrote the proposal to the National Science Foundation, we had just assumed that NASA had all this in digital format and it was already available. And so we put the proposal in, and NSF and the reviewers really thought this would be an enormously valuable effort to support, one because it would advance the speech and language technology, but even more importantly, it would certainly preserve the audio that would’ve come from this, probably the most significant engineering accomplishment mankind has had over the last 100 years. But it would also give people outside of the technology side the ability to start looking at human aspects. How do actually people work collaboratively together? When do they become unhappy about things? And this actually might help motivate kids to go into STEM, we hope. It also might allow us to have a better understanding if we’re sending folks to the, to Mars, how they might actually collaborate in a stronger way.

Host: Tatiana Korelsky wanted to make sure I knew what the review panel thought of Hansen’s proposal, so she read me a part of the evaluation.

Tatiana Korelsky: So this is what they said. “The most creative and original concepts related to the combination of technologies and enhancements which will come together by way of the focused research on spoken audio in the NASA archives. This is a task just beyond the reach of current technology due to the combination of channel conditions, background noise, and the type of speech. Spontaneous conversational speech, over often under stress conditions. So that challenges our characteristic of real-world data, which makes the need to address them pressing if the full potential of information locked within spoken content is to be realized.” After such evaluation, of course, the program decision was to award this project, which started in — the proposal was 2012, so we started at the end of fiscal year 2012 and lasted until 2016, with some extension.

Host: So as I understand it, the basic area of research that he was proposing was something that you found to be of interest. And the choice to have the subject be about the Apollo missions, that historic event, was something that made it even sweeter, even nicer.

Tatiana Korelsky: Of course. Of course. That’s why I say it was a unique proposal.

Host: So you went to the National Science Foundation with a proposal to do this project, assuming that NASA had recorded all those conversations back in 1969?

John Hansen: Recorded them and hopefully, we thought, digitized them.

Host: Well, I was going to make that a separate part of it. So then, you, I assume, the next step is to go to NASA and say, please?

John Hansen: Well, we needed the money first, so, yeah. So we were pretty fortunate NSF said this was a good thing to do. But we still had some concerns. And so we had to resubmit it a second time. It took more than a year. And it was interesting because I was at a conference involving Department of Defense, and there was a gentleman that walked up to me and said, “Well, I hear you have interest in Apollo and NASA.” And I was kind of surprised because I didn’t think someone would know about that, and I started, you know, running off I was, you know, a geeky engineer and said, “Yeah, we’re really excited about this. We hope NSF will fund this the next time.” And the gentleman said that, “Well, yeah. I was kind of involved in the review process, and I can’t officially say anything, but it’s a really good project. You probably need to have someone that is more involved on the history side also involved.” And that was actually a thing that we added when we resubmitted, and it made a difference because it allowed us now not just to focus on the technology, but be able to kind of connect it to society. We really wanted to have something that would allow K-12 type kids to kind of see and listen to the audio.

Host: So it was no longer just the academic investigation of the interaction of the individuals in this group, but that the individuals in this group were the people who landed on the Moon.

John Hansen: That’s right. That’s right. That’s right.

Host: Which people we’d hopefully be a little more interested in.

John Hansen: Yeah, so, I mean, I, a lot of the technology and things that we’ve done with this work over the last 5, 6 years now, we’ve gone, in Dallas, we’ve gone to the Perot Museum pretty much every year for Engineers Week. And we’ve usually brought a, always brought an undergraduate senior design team to the Perot Museum. And it’s nice to sit back and allow undergraduates to kind of show how excited they are in terms of talking about audio and these types of activities. And at least during the Perot Museum, they typically have about 1500 to 2500 kids per day during Engineers Week that actually come in. And they’re little kids. I mean, they’re through K-12 — maybe not through 12. Maybe K-8 is where they’re coming. And that, to me, was really a very enjoyable thing because you always think, well, we’ll develop technologies. It’ll be in the college level. How does that actually help kids that are in grade school, and what might motivate them to kind of go and look not necessarily at being an astronaut, but developing math, physics, chemistry, biology, or something that might actually help support space exploration?

Host: Hansen succeeded at the National Science Foundation, which awarded the first grant in September of 2012 just shy of $400,000 to fund the project. That meant Hansen was ready to approach NASA with his idea and that he was about to get a big surprise.

John Hansen: Right after we got the grant, we came down to NASA. And I naively said, “Well, can you show us where you have the audio?” And Greg Wiseman pointed us to some boxes of tapes, and I’d said, “We’re in trouble here because we thought this was all digitized.”

Host: And that’s not all. Hansen was about to find out that not only was the audio still on big reel-to-reel tapes, but there was no machine that could play those tapes so he could digitize the audio so he could do his research. In the next episode, we’ll start the long, strange trip to a solution to those problems.

[ Music ]

Yep, the story turned out to be too big to cram it all into one episode and do it justice, so we’re breaking it into a few pieces. I hope you’re hooked and will come back for the rest. The Heroes Behind the Heroes Episodes of Houston We Have a Podcast are produced by Greg Wiseman and me with editing and audio engineering by Greg with help from Alex Perryman. Thanks to our guests, John Hansen, Larry Vrooman, and Tatiana Korelsky, and to Norah Moran and Gary Jordan for helping us pull it all together. You can hear all the episodes of Houston We Have a Podcast online at nasa.gov/podcasts, where you will also find some other cool NASA podcasts, including “Welcome to the Rocket Ranch,” “On a Mission,” “NASA in Silicon Valley,” “Gravity Assist,” “The Invisible Network,” “Small Steps, Giant Leaps.” They are all available right there at the same spot where you can find us — nasa.gov/podcasts.