If you’re fascinated by the idea of humans traveling through space and curious about how that all works, you’ve come to the right place.

“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center from Houston, Texas, home for NASA’s astronauts and Mission Control Center. Listen to the brightest minds of America’s space agency – astronauts, engineers, scientists and program leaders – discuss exciting topics in engineering, science and technology, sharing their personal stories and expertise on every aspect of human spaceflight. Learn more about how the work being done will help send humans forward to the Moon and on to Mars in the Artemis program.

On Episode 223, John Uri reflects on the history of the Johnson Space Center after its 60th anniversary. This episode was recorded on October 22, 2021.

Transcript

Pat Ryan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 223, “NASA’s 60 Years in Houston.” I’m Pat Ryan. On this podcast we talk with scientists, engineers, astronauts and other folks about their part in America’s space exploration program, and today we’re going to shift focus to talk about the place in spaceflight history of a particular place: this one, the Johnson Space Center. America’s civilian space program was born with the passage by Congress of the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which went into effect on October 1st, 1958. As the agency got itself on its feet in those first few years, it divided up the work among a number of facilities spread across the country and, in some cases, to centers that did not yet exist. Such was the case when, in 1961, the NASA Administrator announced the completion of a location study, which found that the new Manned Space Flight Laboratory would be located in “Houston, Texas, on 1,000 acres of land to be made available to the government by Rice University.” The official announcement also found it important enough to note that the land borders on Clear Lake and the Houston Light and Power Company’s Salt Water Canal. Well, the name was changed to the Manned Spacecraft Center by the time it opened for business, and years later to the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, and it has served as the home of human spaceflight in the United States ever since. Every single American spaceflight with people on board since Gemini 4 in 1965, the one in which Ed White became the first American to walk in space, have all been controlled from right here. Every single American astronaut has been trained for spaceflight right here. When samples of rocks from the Moon needed to be preserved and studied, that happened right here, too. But how did some scrubby pastureland on a salty lake in southeast Texas come to take its place in spaceflight history? Well, today, on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of JSC, we talk about its history with John Uri, the manager of the History Office at the Johnson Space Center since 2016. Uri’s experienced a lot of this history himself. He has 34 years in the space industry, 28 of those with NASA, and that includes serving as the manager for the Space Radiation Element of the Human Research Program, after 12 years in the International Space Station programs payloads office, which followed seven years as the mission scientist for the Shuttle-Mir program. The history of JSC with John Uri: here we go.

[Music]

Host: John Uri, your long career with NASA began as a scientist; in fact, that’s where you and I met back during the Shuttle-Mir program. Tell me about how you got interested in even working in the space program in the first place.

John Uri: Well, I would tell you, Pat, that probably began when I was about four years old. I was really interested in space from the very beginning, the early space missions, both the American and Soviet at the time. But I really didn’t know how to get into the space program. My initial career goals were to go into science or medicine. I got a BA in biology from the University of Pennsylvania, and I thought I was going to maybe go to grad school, but I had an opportunity to come down here to JSC and work with one of the astronauts. This was back in the early days of the Space Shuttle Program when they were trying to identify the causes of space motion sickness, and I had the chance to work with Dr. Bill Thornton. And that sort of got me into, some would say sidetracked, from my original career goals, but for me it was certainly a turning point in my career. From that point, it just developed into, you know, a lifelong interest, and I ended up coming back here and working with Dr. Thornton some more to analyze some of that data, and this was at a time when the, our program with the Russians was picking up and I had an interest. I had already taken some Russian lessons, so I already knew some of that. As I mentioned, I had an interest in the Soviet program, and so that’s how I started working in the Shuttle-Mir program, I was the mission scientist. And of course when that ended, that was a natural segue into the International Space Station program. So I did similar science management functions there, and then of course I got an opportunity to do some, you know, kind of go back to my original research goals, and I got to manage the space radiation element for the Human Research Program for a few years. And then about five years ago they were looking to restructure the history office here at JSC, and some people knew of my lifelong interest in space history and asked if I would be interested in running the office. And I really jumped on the opportunity, because it’s just been great. I’ve got to learn so much more about NASA history, about the history of the Johnson Space Center and all the things that went on here, so that’s kind of the long-winded answer to how I got from a science background to now running the history office here at JSC.

Host: There obviously was a history office if one needed to be reorganized, but I don’t really think that I feel like most companies or places have their own history office. Is that something that’s more unique to JSC or to NASA in general?

John Uri: Yeah, NASA’s actually had a history office from the very beginning, since I think about 1961, both at the Headquarters level, and each center had at some point some version of a history office, and that changed over the years, you know. Even here at JSC, for some years, the history office kind of disappeared, became more of a records management kind of thing, but other organizations in the government, the armed forces, in particular, the Navy has just an outstanding history program, as do the other branches of the service. And other government agencies do have history offices to, you know, keep track of where they’ve been, and use that history to, you know, define their future, you know, learning the lessons from the past to guide you in future programs. So it’s not at all unusual. It’s just that, you know, support for a history office varies over the years, and what organization it’s located in. And so, they were looking to restructure it, actually moved it into the knowledge management office within Safety and Mission Assurance, which seems like a logical fit with knowledge management. And so, that’s how I kind of came to run the office, so it’s been exciting. We’ve done a lot of great things in the last five years, and looking forward to doing a lot more. It came at an opportune time, because the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing happened in that period, and our office was very much involved in supporting all those activities.

Host: And we’re, today, we’re recognizing the 60th anniversary of the Johnson Space Center. It occurred to me to, to wonder whether or not it’s surprising, or unusual even, that a federal facility outside of Washington, D.C., like this one, would even last for 60 years. You think?

John Uri: Well, I think we’re very fortunate in that, and that has to do with the overall public and Congressional support for the, for the nation’s space program. If we didn’t have that, you’re right, we may not be here anymore. But of course, it started in a very politicized way with the space race with the Soviet Union back in the ’60s but, you know, after we landed on the Moon we started new programs with the space shuttle, space station, and so forth, so that public interest is what has kept us here. You know, there are some NASA centers that are actually older than JSC because they were around, you know, during NASA’s predecessor organization, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. For instance, Langley [Research Center] in Virginia and Ames [Research Center] in California had been around longer, but again, all of that is based on the level of support that the space program enjoys, politically and with the public.

Host: OK, let’s, let’s go back to the beginning, and talk about how did it all begin. We know that NASA got started, NACA became NASA in 1958, but it seemed to be pretty much huddled up around Langley and up around in the D.C. area. And my recollection is that there was a part of it that was known as the Space Task Group, and they were the people who were being sent off to figure out how to put man on the Moon. Is that right?

John Uri: Yeah, that’s right. Yeah, as you said, NASA opened for business October 1st, 1958, and about a month later is when they established the Space Task Group, or STG. You know, we like acronyms here, so STG. And so, and they were originally based at Langley in Virginia, and there was some talk at some point of moving them to the Goddard Space Flight Center, which was established in 1960, and so there was, you know, some discussion about where’s the best fit for the Space Task Group. And their initial purpose was to establish, you know, the first, as you said, the first man in space, which became the Mercury program. And that was going along but, you know, we picked our first astronauts in 1959 for that project, the Mercury 7, and we started flying, the first suborbital mission was Alan Shepard’s in 1961, May 5th, and 20 days later, lo and behold, President Kennedy says, OK, well this is great, but we really want to go to the Moon and we want to do it before the end of the 1960s. And all of a sudden —

Host: And everybody at NASA went, huh? What?

John Uri: And exactly, and so how do we do that? And the Space Task Group, which was the organization dedicated to putting people in space, and they had put one, in a 15-minute suborbital lob; all of a sudden, you know, we’re going to the Moon in ten years or less. So, clearly the facilities they had at Langley were inadequate for that. They needed a, you know, basically a brand-new place, you know, dedicated to nothing but human spaceflight. And so, that’s, that’s how they started looking around. Well, you know, what are we going to do? What does it need to do and more importantly, where are we going to put it? And so, they knew kind of the purposes that were needed for it, you know, kind of a place to have mission control, a place for the astronauts to live and train, where do you develop new spacecraft that were needed to get to the Moon, and a lot of research and development that goes with that, so those were identified as the purposes for this new facility, which originally was just called a laboratory, actually, Manned Spaceflight Laboratory.

Host: Right.

John Uri: And of course, this was all in 1961. Things were happening really fast, by the way. NASA was establishing centers all over the place: the Marshall Space Flight Center in 1960, what later became the Kennedy Space Center in Florida for the rocket launches. So, things were happening fast, and then on top of that, you needed this new center, and somebody had to decide where to put it, and that’s another interesting story.

Host: Well, and as you describe it, they’re looking for a place that, apparently, they felt needed to be physically large. Is that because the development of large pieces of equipment?

John Uri: That was part of it. There were lots of requirements that, you know, they set up, like everybody does, set up a committee to look to study this, and they came up with criteria of what do we need at the center, and so, they identified a few things. Availability of water transport nearby, because as you said, there may be some large spacecraft pieces that needed to be moved that were too large to move on railways or on trucks; near to an airport that basically had all year-round, you know, flying capabilities. They wanted to be near universities to, you know, use that talent pool for engineers and so forth. And also, they preferred a milder climate that could have, you know, 12 months a year kind of operations, and they also wanted it to be near, you know, an area that had some cultural attractions and so forth. So, they came up with a list of about 19 places that got expanded and shortened and —

Host: Nineteen?

John Uri: — a lot of site visits took place. Yeah, and they were all over the country. Remember, some of this was politicized, and a lot of people wanted this brand-new center, you know? Back then, space was the thing, and going into space, and where are you going to put a human spaceflight center seemed very important for anybody that would host that center. And so, this committee went on this trip, and every day they went to a different place and visited the places, and the local Chamber of Commerce came out and presented why they were the ideal place and so forth. And they were, and they eventually narrowed it down to about a short list and two places seem to fit the mold the best, and one was Tampa in Florida, and the other one was near Houston in Texas. And Tampa was actually in the lead for a while because they also wanted a nearby airport or airbase facility, and Strategic Air Command at MacDill Air Force Base was looking to close that facility, and so it seemed like, well, this new center could take over that facility. Well, it turns out SAC, they changed their mind, they didn’t want to close it, and so that avenue kind of closed. And so, Houston kind of became the number one choice because it met all the criteria, both the mandatory and the optional criteria. You know, we had fairly easy access to the, to Galveston Bay and to the Gulf of Mexico because the site in southeast Houston was on Clear Lake and so, basically you had water access. Ellington Air Force Base was close, close by. What was then Houston International Airport, which is now Houston Hobby, was close by. You had Rice University here. You had Texas A&M and University of Texas not too far away. Houston was a pretty big place, even then. It had just cracked the one million population mark in the 1960 census, and so it was up and coming. The oil industry was here, so there were a lot of engineering, a lot of construction. So, it met a lot of those criteria. And the other criteria that it met is it had very supportive politicians, both at the local and at the federal level, and so that was kind of, that kind of support doesn’t hurt. And so, in the end, they decided Houston is going to be the place and they made that announcement on September 19th of 1961, and by then it had been renamed to the Manned Spacecraft Center.

Host: Now to say that it was being put in Houston may be factually accurate, but the site was pretty far out from Houston and had virtually nothing around it. There’s a famous photograph taken by a NASA photographer, Andrew Patnesky, of the site, with cattle grazing on it, and there was nothing around it. There was, my recollection from seeing some old photos was that really the only building in the area, was the West Mansion. There was, there was nothing here.

John Uri: Yeah, you’re absolutely right. This was basically Texas coastal prairie, and some of that had been converted into ranch land so, and some rice farms, and there were some fishing villages. But you’re right, and Houston, of course, those who know Houston, now it’s a big sprawl but back in 1961 the city didn’t extend all the way down here. In fact, the 610 Loop hadn’t even been built yet, or only parts of it had been finished, and so —

Host: And the Gulf Freeway was still under construction but —

John Uri: — and it was still under construction —

Host: — it still is today. [Laughter]

John Uri: — just, and there you go. It’s absolutely right. Has been, I’ve been here since 1987: one section has always been under construction. That’s a Houston inside joke.

Host: 1966 for me.

John Uri: There you go. So anyway, so yeah, you’re right. This was pretty much just coastal prairie, and there was not a lot of people living here. The population of this area, which included, like, Webster, which was mostly a farming town, and Seabrook and Kemah, they were fishing villages, was about 6,500 people total.

Host: Total.

John Uri: And so, compared to today, which is about, you know, that same area probably has about 100,000. And so, there’s one little road, a two-lane road called Farm to Market 528 that went by here. And so, but what happened was the Humble Oil Company, which is now Exxon, owned a lot of the land here, and they had donated 1,000 acres to Rice University, that Rice was hoping to attract some federal facility. They initially talked to the Atomic Energy Commission about building something here, but those plans fell through and then all of a sudden, hey, somebody is trying to set up a Manned Spacecraft Center somewhere, and they chose the Houston site, and it turned out that then Rice donated those 1,000 acres to the federal government. So, you know, a cost is always a consideration for these kinds of things —

Host: Right.

John Uri: — and that was a pretty good cost. And so, that’s why it was, it was settled here, but you’re right, it was very different from what it is today. And so, in fact, two days after the announcement, Bob Gilruth, who was the director of the Space Task Group, and later would obviously be named the director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, he and some of his top aides came down to visit the site, and what was interesting is, some people may remember Hurricane Carla, that came through here about ten days before their visit. And so, they, you know, they got off their plane at Houston International, they drove down here, and of course, the Gulf Freeway was, I think, a two-lane freeway, and like I mentioned, a two-lane road out here, and there were, you know, boats lying by the highway that had been pushed up by the hurricane, there was a fair amount of destruction around here, and they’re thinking, my goodness, where are they sending us to? Now bear in mind, all these folks have been well established in Virginia, they had homes and families and schools and churches and so forth. And they want us to move here? And of course, in September, it’s still pretty warm in Houston, and there’s these things called mosquitoes and so, there’s, and they come down here and they look at the site, and it’s basically wilderness. The day before, somebody had come by to see it, and one of the hunters was around, he had just shot a wolf on the site. And so, there are lots of deer and alligators and all kind of critters. But anyway, they kind of saw the vision that yes, we could turn this into something, and this is where we’re going to lead human spaceflight from in the next few years, and that’s kind of how all that, all that developed. And it actually —

Host: And of course, the deer are still here.

John Uri: The deer are still here, and thanks to the pandemic, they’ve become very, they’ve kind of taken over the site. You can walk around these days and see them everywhere.

Host: And be careful to drive —

John Uri: Anyway, they had the vision. They could, they could see how this basically empty prairie could become, you know, the centerpiece of human spaceflight.

Host: And you, as you noted before, the “end of the decade” clock is already ticking. President Kennedy had started that earlier in 1961, so they have less than ten years, and they show up here to a place where there is nothing, and they’re, and they’re on a deadline.

John Uri: That’s right.

Host: How long does it take to, I mean, do they start bringing people into Houston right away? Where do those people go to work? How long does it take to build the Manned Spacecraft Center, to have work being done at this desirable location?

John Uri: Well, I will tell you, I think by today’s standards, things happened at a lightning-fast pace. As I mentioned, you know, NASA announced on September 19th that Houston, or southeast of Houston, that site had been chosen for the Manned Spacecraft Center. You know, Bob Gilruth was here two days later. By the first of October, an advance team had already come to Houston to start looking for temporary office space because, you know, things were moving. Like you said, the clock was ticking, and they had to start bringing people down here, even as they were letting contracts for the construction of the new site on Clear Lake. And so, I think October 1st or 2nd, the first team came down. They actually, they set up temporary office space in a vacant store at the Gulfgate Mall…

Host: In a shopping center.

John Uri:…at the corner of…a shopping center; It’s gone by different names over the years, and it’s, you know, it’s at the intersection now of the Gulf Freeway and the 610 Loop. Of course, the 610 Loop essentially ended there at [Interstate] 45 [the Gulf Freeway], you can just see the feeder roads in the early ’60s before they built out the whole Loop freeway. And so, there they set up shop there, and they started talking to the Corps of Engineers who are going to build a site at Clear Lake, or design the site and clear it, and then they also started looking for temporary office space for the engineers who were going to start coming down here and start doing the work of the Manned Spacecraft Center here in Houston, as the site was being built. So a lot of balls were being juggled, a lot of things were happening, and they did, over the next year or two, lease facilities in 13 different buildings through southeast Houston to, you know, to house the engineers, you know, they had to have a Headquarters building, they had to have places for the Gemini program for all the logistics. And so, these different buildings kind of served their purpose. And just as an aside here: for fun, in the last couple of weeks, I decided to go on a photo safari and see if I could find these buildings around Houston, if they’re still there.

Host: Neat.

John Uri: And most of them still are.

Host: Right.

John Uri: You can find them, and unfortunately, most of them, you don’t know that it was a former NASA building, so the history there, unfortunately, is not documented. A couple of buildings have been torn down, and they’ve just been repurposed for other things. One of them is a convent, one is an auto glass store. I mean, it’s, it runs a variety of different things, but it’s a fun historical trip. And what was really amazing, I’m sure traffic in Houston was not as bad as it is today, but it took a long time to go from one building to another, so it must have been a burden on those managers and engineers to go from one facility to facility to another back in the day before, you know, we had the main site here on Clear Lake. And again, if you drive up the Gulf Freeway into downtown from here, you unknowingly pass by some of these buildings. Some you can actually see from the freeway, they’re still there, which I think they out to have big signs that says, “former home of NASA,” but that’s my own personal view.

Host: History was right here. Yeah.

John Uri: History is everywhere through Houston.

Host: When they, at this point when they started, I assume that they’re bringing a lot of the people who were at the Space Task Group at Langley, but are they also hiring new people who were already in Houston?

John Uri: Yes, it’s a combination of both. I think they brought down about 750 engineers in late 1961, I think by November or December. So, like I said, things were moving quickly. This was still 1961. We had flown two suborbital missions. We hadn’t even flown John Glenn yet.

Host: Right.

John Uri: People were already moving down here to start setting up the functions of the Manned Spacecraft Center. Most of the Mercury stuff stayed at Langley, at the STG, because they didn’t want to disrupt an ongoing program, but any future programs like Gemini and then Apollo, those functions were transitioned to the Manned Spacecraft Center pretty early. And then they also hired people here locally. You know, there was, like I said, a good talent pool. There were the universities here, there was the petrochemical industry, there was a healthcare industry, so there was a good number of folks they hired, and that hiring went on continuously as they staffed up to 3,000 people or so by 1962, so again, very fast pace. And then of course, we can talk about the construction of the Clear Lake site. That started in 1962.

Host: Right. Well, and I’m also thinking that there are, because there was nothing at the site where JSC is right now, there were also no places for people to live. People who are coming to Houston and were driving 30 or more miles to get to work. I knew some people in the neighborhood where I grew up in, in southwest Houston, that worked at NASA and I went and looked it up there — it was like 35 miles each way to get to work without the freeway system that we have today.

John Uri: That’s exactly right. It was all back roads. The Gulf Freeway was the only freeway here. I guess [U.S. Highway] 59, the Southwest Freeway, was partially completed, and the 610, which everybody uses, was only very partially completed. So, yeah, and you’re right, and some of the people found homes, tried to find homes like in Friendswood, but Friendswood was a small town. It had one police car. I mean, just the support system wasn’t really built up. You know, Seabrook and Kemah were, you know, not even bedroom communities yet. They were fishing villages. And so, eventually, they started to get built up, but most people ended up, like you said, finding homes closer into where the temporary buildings were in southeast Houston and in other parts of town, like south, wherever there, you know, was available. And they ended up driving longer distances on essentially backroads.

Host: But the establishment of the Manned Spacecraft Center here drove that other kind of development, residential and commercial development, in the Clear Lake area.

John Uri: Oh, absolutely. You know, the new little town of Nassau Bay, you know, that did not exist before the Manned Spacecraft Center was here, and the biggest development was Clear Lake City, kind of northeast of the center, which is now just a huge development. And all the other cities benefited. League City, it’s now I think, over 100,000 population. Even Seabrook became a larger bedroom community and Webster grew a little bit. And so yeah, but all that took time. So, by about 1970, I think the area around here had a population of maybe 30,000/35,000. So, and of course, it just kept growing over the years. It’s not only the Manned Spacecraft Center, but all the supporting industries, and businesses, you know, they needed people to live somewhere, and then of course, there was the recreational part with the boating and, you know, it just kind of blossomed from there. It’s really interesting to see the old pictures, you know, the aerial shots of the center, as it was built, and you can also see in the background, how the residential areas are also kind of springing up all over the place.

Host: Yeah, if you do look at a few as if in a time lapse, and you can see new stuff start to appear around the periphery.

John Uri: Oh yeah, and of course, you know, along with that was, you know, traffic, and so the roads had to be widened from two lanes to four to six to eight or whatever. And the Gulf Freeway had to be expanded for all the additional traffic and, you know, all that stuff just kind of takes on a mind of its own.

Host: Tell me, when did people actually get on-site? When did people start working at what we know today as the Johnson Space Center?

John Uri: OK, the first people that started moving on-site were a lot of the technical services people. That was in late 1963, but it was just a handful of people. Only a few of the buildings at that point had been certified to be open. It was in 1964, in the spring, February to April, where there was a big push to bring a lot of folks on, and that’s when actually, Bob Gilruth, the director, he moved his headquarters from the Farnsworth & Chambers Building on Wayside to the project management building, which was Building 2 at the time, on the ninth floor. I think that was in March or April of 1964, and that’s when a lot of folks started moving in. And by July 1st of 1964, all the leases on the temporary buildings had expired, and so everybody was on-site. Not all the buildings were completed, of course. There was construction still underway, and even through the ’60s, there were more facilities added to the center, but NASA felt well enough to have an open house in June of 1964. And, you know, tens of thousands of people showed up that one weekend — they actually had to extend it to subsequent Sundays to have a chance for other people to come see. Of course, some people I’m sure came back repeatedly because the kids said, Mom, Dad, I want to go to NASA again, because they had set up, you know, a model of the lunar module, there was a Gemini capsule, there was a Redstone rocket, there were all these things that kids, and adults, could come see, and everybody was curious all through Houston, I’m sure, were curious as to, you know, what is this Manned Spacecraft Center all about? And when they were in these dispersed buildings, there really wasn’t a cohesive identity to the Manned Spacecraft Center. Once the center was open, clearly, it had its, had its own identity. But there was still not a lot of places to live around here because, you know, Nassau Bay I think was just getting started. Clear Lake City started in 1965, I think. NASA Road 1 wasn’t even called NASA Road 1 at the time, that didn’t happen till 1965. And so people lived in more outlying areas, like you mentioned, in Sharpstown, or in the city, or in Friendswood. That had actually already existed and was starting to develop. Webster had a few places added and same with Seabrook, and so those bedroom communities started growing up, but, and by the late ’60s, it really became a more cohesive community here when, when Clear Lake City had enough housing for everybody and, you know, schools were getting built, churches were getting built. And so, the communities were really centered around space and the Manned Spacecraft Center. You know, playgrounds had, you know, rockets as, you know, for the kids to play on and so forth. So, there was a definite space identity to this part of Houston. And of course, eventually Houston became known as Space City: that’s actually its only formal nickname, all the other things you hear about, Bayou City, those are not official names, but the Houston City Council adopted Space City as the official nickname of Houston.

Host: In the ’60s, as people start to work on-site at the Manned Spacecraft Center, we’re also moving in the, you know, in the reality part of it — not reality, but the fact that what other people around the country can see, we’re moving from Gemini, we’re moving to Apollo. So, I’m thinking that serves as more of an impetus to even greater growth around the Manned Spacecraft Center.

John Uri: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, Apollo was a very complicated project, you know? Going into space in general is complex and difficult, and people were doing things that had never been done before, developing procedures and hardware and life support systems. How do you rendezvous in space? But, you know, when you say we’re going to the Moon, that kind of kicks it up a whole other notch that, you know, we’ve never really done, if you will, interplanetary navigation, there’s new training facilities that have to be set up, there’s new spacewalking techniques that need to be learned, and so that required, you know, more and more engineers to come onsite to support those new functions, and that also led to new buildings being constructed onsite. So, there was, as I mentioned, continuing construction, through the 1960s. You know, mission control was already built in 1964, and it actually started following Gemini 2, which was the second uncrewed Gemini flight, in early 1965; it followed the first crewed flight, Gemini 3, and then starting with Gemini 4 it became the only Mission Control Center, and has been ever since.

Host: Right.

John Uri: And of course, the name Houston became synonymous with when astronauts would call down to mission control, they would use Houston as the callsign. And so everybody around the country, around the world, heard the word “Houston” all the time associated with spaceflight. So, Houston really had that very close association with human spaceflight.

Host: As, and I guess it’s just inevitable, as the Apollo program helped the center in the area grow, that once the Apollo program ended, it had a reverse impact.

John Uri: Yes, that’s true, and that actually started even as the Apollo program was still ongoing. You know, the budgets, if you look at the NASA budgets, they actually peaked in 1966 and started to decline, and of course, that was because centers were being built and rockets were being built, and all that kind of trailed off in the late ’60s. And the workforce, you know, those layoffs or reduction in forces — they’re called RIFs — started happening in the 1970-1971 timeframe. You know, that’s when the severe budget cuts started happening at NASA. There were a lot of other things going on in the country at the time. You know, the Vietnam War was still going on, there were a lot of social programs that, you know, had people’s attention. And, you know, unfortunately, after we landed Apollo 11 in 1969, we kept going back. You know, after a while, some people lost interest, said hey, we’ve already done it, time to do something different. And so, actually the last three planned Apollo missions were canceled, partly due to budget cuts, and, and so, the layoffs started in 1970-1971, and that was before the shuttle program really kicked in. And so, there was a dip, and so there were probably lean years around here as some people lost their jobs, they might have moved on to the petrochemical industry, because, you know, the skill mix may have transferred there.

Host: Right.

John Uri: And so, there was some of a dip. But, you know, surprisingly, the area survived pretty well through the lean years. And of course, once the shuttle started picking up in the 1970s, that was also another major effort, and that really helped to bring the expertise — not necessarily the same people back — but certainly the expertise back to the center.

Host: To, that helped to drive new work and new employees.

John Uri: New work, new growth, again, the shuttle was something radically different that hadn’t been done before. There was a lot of testing to be done. New facilities had to be built here on-site for, especially for spacewalk training, and we can kind of go into, you know, how the center evolved in certain ways to deal with these new and complex programs. Just to use that example: for the Apollo missions, they used a very small pool for spacewalk training. They realized during Gemini that using water, you know, a swimming pool for spacewalk training is probably the best way to simulate weightlessness. And that carried over into Apollo, but they were small spacecraft relatively, so they used basically an above-ground pool, if you will. It was like 25 feet deep, maybe 30 feet in diameter, so not very big. But then the shuttle comes along. It’s, you know, the shuttle is, its payload based 65 feet long. Well, then you need a larger pool to train for spacewalks, and so they built, again, to, to adapt to the new changing programs. They built the Weightless Environment Training Facility, which they actually put in the old centrifuge building, but it was a swimming pool that could handle the entire payload bay of the space shuttle. And so, there was —

Host: I’ve been in it.

John Uri: — and that’s just one aspect of it. New simulators had to be brought in, and that’s really what engendered a lot of the growth around here in terms of new engineering skills and other things that were needed.

Host: Another change that was happening around the transition from Apollo to shuttle was that the name of the center changed. It became the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in 1973, following the death of the former president.

John Uri: Yes, and you know, within a day or two after President Johnson’s death, I think it was Senator Bentsen, Lloyd Bentsen of Texas, put a resolution in through Congress to formally change the name. It’s a government facility, so it has to go through the government process, and that was approved unanimously. President Nixon approved it, and it seemed logical, you know: President Johnson was from Texas, he was a huge supporter of the space program from the very beginning, he was instrumental in establishing NASA back in the 1950s. He probably played some role, maybe indirectly, in getting the Manned Spacecraft Center put here in Houston, in Texas, back in —

Host: Some? Some, you say. [Laughter]

John Uri: Well, you know, that’s debatable. I mean, Johnson worked through a lot of influence without actually having to do anything directly, and so —

Host: Yes.

John Uri: — if he made a suggestion, people would follow it, and then, you know, other people would carry out those kinds of tasks, but yeah, obviously, there was a, and he was not the only Texan who was very much interested in the space center.

Host: Oh, no, absolutely.

John Uri: There were many, many, many others, and so that certainly helped. But ultimately, if you look at the data, it’s actually a pretty good, logical place to put it, it met the criteria, so anyway. So, it seemed logical to name the Manned Spacecraft Center after a president who hailed from Texas, who was a space supporter. And so that happened, I think, in February 1973. They had a formal dedication ceremony in August of that year, and his widow, Lady Bird Johnson, was here, and many members of the Johnson family were here for that dedication. They dedicated a bust of Lyndon Johnson that’s still here. And as it turns out, the Skylab astronauts happened to be on orbit at the time, and they radioed down their, you know, congratulations for the ceremony and so forth, so. That was one of the first times that, because it was a long-duration mission, we had the luxury of doing one of those kinds of events, of having the Skylab crew kind of phone down their congratulations on a, on an event like that. So and that’s the, that kind of stuff happens all the time now, we kind of take it for granted, but back then, that was a pretty big deal.

Host: Right. You touched on this, let me see if I can get you to go a little further. We’ve, we’ve made the point that the Johnson Space Center is known as the home of mission control and the home of human spaceflight, but over the course of its history, it’s had a lot of other features and other programs here that are prominent in the history of the center. Talk about what else has happened at the Johnson Space Center over these years.

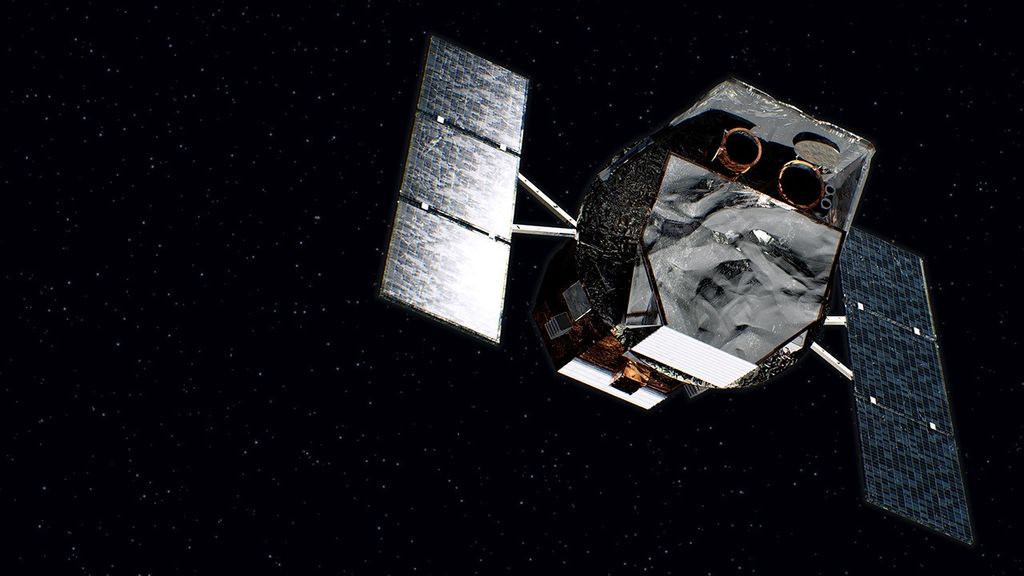

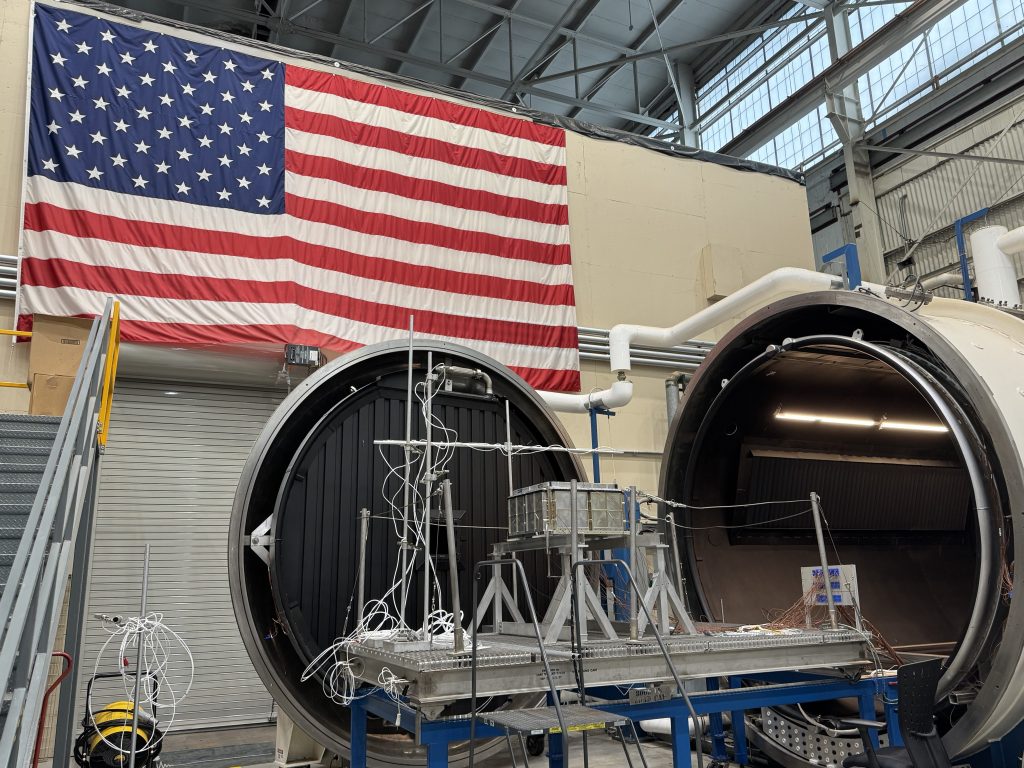

John Uri: Well, we have facilities here that are just, that are unique. One example is this Space Environment Simulation Lab[oratory]. It’s called, we call it SESL for short, basically, these two large vacuum chambers that were used, initially, they were designed for the Apollo program, but as many things at NASA, they were over-engineered, and they were much larger than the Apollo spacecraft. They could handle much larger spacecraft. We used it a lot for, even in Skylab, and other programs, but it was large enough to handle large satellites, too. So, there was, in the mid-’70s, the Application Technology Satellite from the Goddard Space Flight Center, they, it was deploying this huge umbrella-shaped antenna and they weren’t sure, the Goddard folks weren’t sure how that would happen in a thermal vacuum environment. And so, we had the chamber to test it. More recently, the James Webb Space Telescope was here, and also tested in that same, chamber A in the SESL, back in 2017. It was here for about seven months, and a lot of people got to see it while it was here, and so forth. And of course, hopefully, we’ll see it launch here in a couple of months.

Host: Right.

John Uri: But so, our facilities, because they’re so unique, can be made available to other NASA centers. We’ve also, the Neutral Buoyancy Lab[oratory], which is the next step in the evolution of spacewalk training because again, after shuttle, we need a larger facility for space station, so we built a Neutral Buoyancy Lab at the Sonny Carter [Training] Facility. Folks from the petrochemical industry have used it for dive tests on, on oil platforms and so forth. So, our, because of the uniqueness of our facilities, they can be made available to other, you know, non-human spaceflight organizations or even non-spaceflight organizations. The other thing I would mention is, you know, the Apollo astronauts brought a lot of lunar samples back, 700, 800 pounds worth of lunar rocks and soil, and so we have that curation facility here on site that, again, is very unique, for obvious reasons. They’ve also handled other samples from, that were returned, you know, from cometary dust and interstellar particles and things like that. And so, they’re also curated here for other project, again, because we have the unique facility that, you know, has been here since the ’60s and ’70s.

Host: We also have a lot of scientists who are breaking ground in all kinds of stuff, not just during the Shuttle-Mir Program but the International Space Station program, too. And a lot of that work is located at the Johnson Space Center.

John Uri: Sure, I mean, my, my expertise, because that’s the place I come from, obviously, the biomedical scientists who are here, you know, to keep our astronauts healthy. You know, a lot of those experiments have applications to human health here on Earth, and now we obviously have scientists from other universities, but we have a very talented pool of biomedical scientists that look at, you know, changes in the human body, that look at radiation effects in long-duration spaceflight, and so forth. And that’s all done here too, again, because we’ve had this need to protect our astronauts and make sure that they stay healthy on these long-duration flights, and as we look now to going back to the Moon, and even further, there’s a whole new level of risk out there, particularly with radiation but other things as well. And so, they’re very, very much looking into those aspects. There’s lots of engineering tests that happen here that have uses outside of the space agency. We’re also helping with the, you know, the VIPER (Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover), the robotic explorer that will go to the lunar South Pole. JSC has a large component in developing that vehicle. And so it’s not, you know, yes, it’s a human spaceflight center, but because of the expertise it’s almost inevitable that we also are able to help out other spaceflight groups and even people outside the, the space industry.

Host: The fact that it’s been involved in all of those different things is, it has enjoyed a lot of just general interest. You refer to the open house they had in the early ’60s; it was in the early ’90s, I guess, that the decision was made, ultimately happened about ’94, ’95, where they move the visitors center from the Johnson Space Center offsite, and they created a whole brand-new thing. Space Center Houston, it’s called, and the director of Space Center Houston told me in a previous podcast, number 85, that Space Center Houston is now the top destination in all of Houston for out-of-town visitors.

John Uri: Yes, and I —

Host: More people come to Houston to see that than anything else in Houston.

John Uri:[Laughter] It is amazing, isn’t it? But I mean, for me, that’s almost a natural. Why wouldn’t they? But yeah, he’s told me the same thing, and so, I guess I have to believe him. It is true based on the, based when you go there, it’s always packed and, you know, now the last few years I think they’ve done a tremendous job of making it far more educational versus just entertainment value, and I think people value that a lot more, because yes, it’s good to be entertained, but you also want to get something out of it. You want to learn something, and so, you know, they have lectures and so forth. And I’m not here to pump up their visitors numbers because they’re doing fine already, but I think the decision was a good one for several reasons. You know, back in the ’90s, I’m at my first time here at JSC was in the, in the 1980s, and I remember going to the old Visitors Center in Building 2 and it had some great artifacts, but you know, as the space program evolved, you know, there are obviously more artifacts coming in, and larger ones coming in. And so, that facility just wasn’t large enough to handle things like the Skylab trainer — they literally built Space Center Houston, the building, around the Skylab trainer. It was so big they couldn’t have gotten it into the building if they built the building first.

Host: Wow.

John Uri: So, and that’s, you know, that’s just a wonderful thing to walk through because you get a feel for how big this space, you know, America’s first space station in the mid-70s, was huge. And so, and they have other things too, and of course, now they have the shuttle and the 747. They’ve got the Falcon 9 rocket. They’ve just had a lot of things that we couldn’t have really kept here on-site. Now, we do have the Saturn V, which is again, it’s you know, people can go on the tour and come see, come on-site and see that and they can also go tour some of the buildings, but it’s in a controlled fashion. Like I said, the first time I was here, tourists could just wander on-site from building to building on a pre-designated path. You know, of course after 9/11, with the heightened security, that would have proved impossible anyway —

Host: Right.

John Uri: — and so that kind of, it kind of came out well that the center, the Space Center Houston, which is adjacent to us here, is a perfect way to show off with what JSC and NASA does and give a chance for the public to see these exhibits, and also come on-site on the tram tours and see actual work happening. Like in Building 9, they can see the space station training modules and so forth, and go through the mission control, which is historic. And I forgot to mention, there are two places here at JSC that are on the National Historic Registry. One is mission control, the other one is the SESL, the thermal vacuum chambers I was talking about earlier. They’re both on the NHR list since the 1980s because I mean, truly historic things happened there and continue to happen. So yeah, Space Center Houston is great. Moving it offsite was probably a great decision, especially in hindsight with what’s been happening in the last 20 years.

Host: And we’ve seen, as we’ve talked about this, how the presence of NASA at this location has driven development. The surrounding community has made that contribution. When NASA has contracted, it’s lost some of that. As Artemis now starts to ramp up, we expect that JSC is coming back even stronger.

John Uri: Yeah, absolutely, and again, that goes to my earlier point that we continue to have public support and we have, you know, Congressional support, bipartisan. You know, NASA budgets are usually passed by a pretty good bipartisan margin, which in these days is pretty unusual. And so, it’s great that we benefit from that. We have all these great future programs to look forward to, you know, a wonderful history that we base all that experience on, you know, 20 years of operating a space station, 20-plus years. We’ve been to the Moon, we can take those lessons for the new programs for Artemis. We can work with, you know, as we’re, you know, collaborating on the VIPER rover, it’s also collaboration with other centers, with Ames. And so, all that stuff just means it’s become a much more integrated program, and clearly, because it’s a new program, we’re building, we’re bringing in new simulators, because obviously the astronauts have to train on Orion, so that’s been another evolving facility here on-site is the facility that does the training and simulators. And obviously, they’ve had to be changed out from Gemini to Apollo to shuttle to station —

Host: Right, right.

John Uri: — now to Orion. All that stuff just means continued growth, and I think from my perspective, you know, looking at the last 60 years of history, yeah, we’ve had a few, I wouldn’t even call them dry spells but, you know, dips, because budgetary things and short hiatus in human spaceflight, it’s always picked back up. But now we don’t have a hiatus because space station is good to go for, hopefully, till 2030. By then we’ll be flying Artemis, so it’ll be just a continuum and an expansion of human spaceflight beyond low-Earth orbit, and that can only mean good things for the Johnson Space Center.

Host: John, it’s been great to talk about that history. I love it, too. Thank you for sharing the expertise. I appreciate it.

John Uri: Well, it’s been my pleasure, Pat. I always enjoy talking about this.

[Music]

Host: John Uri had a little story; I’ll tell you mine. My family moved to Houston in the summer of 1966, and it was either that fall or the next one when my grandparents came to visit, and Dad took us all down to see NASA. We drove straight through the front gate because there were no guards. We parked next to the Visitors Center and walked right into the auditorium where we watched a movie about NASA, and then we walked down a long hall to the museum where there were a few flown spacecraft and other artifacts that were on display. All in all, it was pretty cool. About 30 years later, I came to work here. I was shown my desk, in that same long hallway outside the auditorium, and I spent a lot of time where that old museum was located: it’s now our TV studio. It’s the largest one in the whole city. Still, pretty cool. I’ll remind you that you can go online to keep up with all things NASA, all of NASA not just at JSC. That’s at NASA.gov. It would also be a good idea for you to follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram; you will thank me. When you go to those sites, you can use the hashtag #AskNASA to submit a question or suggest a topic for us, just remember to indicate that it is for Houston We Have a Podcast. You can find the full catalog of all of our episodes by going to NASA.gov/podcasts and scrolling to our name. You can also find all the other cool NASA podcasts right there at the same spot where you can find us, NASA.gov/podcasts; very convenient. This episode was recorded on October 22nd, 2021. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Gary Jordan, Norah Moran and Belinda Pulido for their help with the production, to Andrea Dunn for helping make the arrangements, and to John Uri for guiding our trip through the beginnings of America’s human spaceflight history. We’ll be back next week.