If you’re fascinated by the idea of humans traveling through space and curious about how that all works, you’ve come to the right place.

“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center from Houston, Texas, home for NASA’s astronauts and Mission Control Center. Listen to the brightest minds of America’s space agency – astronauts, engineers, scientists and program leaders – discuss exciting topics in engineering, science and technology, sharing their personal stories and expertise on every aspect of human spaceflight. Learn more about how the work being done will help send humans forward to the Moon and on to Mars in the Artemis program.

On Episode 158, Chris Culbert and Camille Alleyne, project manager and deputy project manager, respectively, for the Commercial Lunar Payload Services initiative, explain how NASA will use commercially-built and -operated landers from American companies to send payloads to the surface of the Moon. This episode was recorded on July 24, 2020.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 158, “Moon Deliveries.” I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight. I hope you tuned into last week’s episode on the lunar “Gateway,” where we talked with Dan Hartman and Lara Kearney. This is a critical element of what makes up NASA’s Artemis program, returning a sustainable human presence to the Moon, and we’re doing so with international and commercial partners. Now, before we get the boots of the first woman and next man on the Moon, American commercial partners will be sending payloads to the surface on commercially built and operated landers through an initiative called Commercial Lunar Payload Services, or CLPS for short. Landers, science and technology payloads, rockets, and landing sites have already been identified in this exciting new chapter of lunar exploration. So, to tell us more about the history, purpose, and progress thus far for this effort is Chris Culbert and Dr. Camille Alleyne, project manager and deputy project manager, respectively, for CLPS. So here we go. Commercial landers and NASA science coming soon to the surface of the Moon, with Chris Culbert and Camille Alleyne. Enjoy.

[ Music]

Host: Chris and Camille, thank you so much for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast today.

Chris Culbert: You’re welcome. Thank you for having me.

Camille Alleyne: Thank you, Gary, for having me.

Host: Wonderful. I am very excited to talk about CLPS and very interested to see what this is all about. I’ll be honest. I had to do a lot of research from the ground up on this one just understanding what this is, and I’m so glad to have you both on — the people that are actually leading this effort. It’s very, very exciting. Let’s take a step back first and understand who is leading this. Chris, I want to start with you. Talk about yourself and your background. What got you to this position leading the CLPS effort?

Chris Culbert: Sure. OK. So, I’ve been around JSC for a long time now. I actually was the chief technologist, the center chief technologist, when the center needed some help running the evaluation board that was setting CLPS up. And I was having so much fun, I gave up the chief technologist job and stayed in the role.

Host: [Laughter] How about that? You have an extensive career with NASA supporting exploration and human spaceflight. Is that right?

Chris Culbert: Yeah. So, I’ve been here — I’ve done almost everything you can do in the — at the center, in many ways.

Host: I love it. I love it. Now, Camille, you’re sort of the same. You also have a long career here at NASA.

Camille Alleyne: I do. Mine is going on 20 — I think 25 years this year.

Host: Congratulations.

Camille Alleyne: Thank you. Mine started at Kennedy Space Center working on the space shuttle as a flight systems test engineer. Went through Headquarters in the early Constellation days and then came to JSC 13 years ago as the Orion crew module systems engineer. Since then, I’ve served in the International Space Station program as the associate program scientist. I spent a year at Headquarters actually, working in the Science Mission Directorate, which was really new for me because up to that point, I had only done human spaceflight. And so that was a great experience and really led me to the position I’m in now as the deputy manager for the Commercial Lunar Payload Services, which is — yeah, and we’ll talk about it. But my experience at Headquarters at SMD [Science Mission Directorate] really led me to this program, which has been really, really exciting.

Host: Wonderful, Camille. Now I’m going to stay with you because you already alluded to it. Commercial Lunar Payload Services — what is this, Camille?

Camille Alleyne: So, Commercial Lunar Payload Services is one of NASA’s most innovative public-private partnerships to date. It is our — we will be leading lunar exploration efforts for the agency as early as the fall of 2021. And we’ll talk a little bit about that, but it’s really a delivery service that we are buying from our commercial partners — something akin to FedEx or DHL to the Moon, where you buy — we have science instruments that we want transported to the lunar surface, and we are going to pay commercial companies to do — to provide that delivery service for us, “us” being NASA.

Host: Interesting. So yeah, instead of us building these landers, we are asking commercial companies to build them for us. And then what it sounds like is that we have a lot of payloads or science and technology instruments and demonstrations that we want to put on these landers. Is that right?

Camille Alleyne: That’s correct. And I would correct one thing.

Host: OK.

Camille Alleyne: They’re not building the landers for us. They’re actually building their landers. These are their transportation vehicles, and we are just paying for the ride for our instruments to the surface. So, we don’t — we would not own the landers. The commercial entity owns the landers, but they’ll transport our instruments for us.

Host: Interesting. Now Chris, you mentioned that you were there when CLPS — the idea for CLPS was first coming about. Tell me about the genesis of this idea of this project.

Chris Culbert: Sure. The origination goes back into the 2017, you know, 2018-time frame. As the agency was having success with commercial cargo and commercial crew, there was some discussion about how we apply some of what we were learning there to what was going to become the Artemis program and the ideas in going to the Moon. So, the agency had already started work with some of the Google XPRIZE competitors, private companies who were competing for Google X money to go to the Moon. We were providing some technical support through a program called [Lunar] CATALYST, (Cargo Transportation and Landing by Soft Touchdown) but the obvious next step would have been to take the development a little further down the road — give the vendors an opportunity to do what they do best while letting NASA focus primarily on the science and the technology we cared about. So, the strategy was built out of Headquarters. The Science Mission Directorate was asked to lead the program. They put together a source evaluation process that I led. The procurement was actually led out of NASA Goddard, and we put nine companies on contract. Putting them on the contract didn’t actually win them any delivery service awards. All it did was said these are the companies we believe are capable of competing for task order awards. So, we spent most the year of 2018 going through the evaluation process and getting ready for the master contract. And then we awarded that near the end of 2018. And going into 2019 and beyond, we started working towards task orders.

Host: Interesting. Now how does this framework of adding all of these commercial companies to a contract in such a way that you described — how does that compare to how NASA used to do business when it comes to these different either exploration — different exploration efforts or other efforts? Is this sort of similar to what we’ve seen in the past, or is this a whole new thing?

Chris Culbert: This is pretty new, or at least the approach NASA’s taking is fairly new. We’re relying entirely upon the vendors’ processes and vendors’ hardware. As Camille noted, we don’t even — we don’t own landers. We don’t even evaluate the landers. They get to make their own decision about how to get to the Moon. They’re responsible for contracting with the launch service providers. The simple model that we’ve talked about most frequently is think of FedEx to the Moon. We’re going to hand them a package, and they call us when it gets to the Moon.

Host: [Laughter] I love that. Now, we’re talking about the Moon here, and you already mentioned this program called Artemis. Can you describe what Artemis is and then how CLPS folds into that?

Camille Alleyne: So, Artemis is our human exploration of the Moon, right? So, it’s sending the first woman and the next man to the Moon, but in a different way than we did it back in the Apollo era, right? We — in the Apollo era, we went unilaterally, as a country, to the Moon. This time, we are bringing commercial partners and international countries. We’re working with these entities to go to the Moon and be there in a sustainable way exploring the Moon so that it is used as a platform for us to eventually send humans to Mars.

Host: Interesting. Now, Camille, you already mentioned when it comes to CLPS, these landers are owned. They are the companies. They are — they’re not NASA’s. The company will own and operate this lander. Why are we doing it this way? Why do we need a commercial service rather than just making something ourselves?

Camille Alleyne: Well, I think what we have found working with our commercial partners in the last few years is that, one, they’re very agile and pretty nimble — much more than the government is — and they come up with more innovative solutions that sometimes we don’t have as a government entity the bandwidth to explore as much. And so commercial companies, because they are driven by, you know, funding, our limited funding — in this case, XPRIZE funding — they’re more innovative in terms of their solutions to the problems we have, and so they come up — and having a lot more companies allows the government to have a better price point for these services. So, competing them across the commercial companies really allows a more competitive price for the government and more innovative solutions. So that’s why commercial.

Host: So, Chris, there’s a lot of science and technology that we want to get to the Moon through CLPS, but I want to kind of understand why are we doing it this way. Why are we doing it through this project to have commercial companies design landers rather than just kind of fold it into human missions and, you know, have humans, whenever they’re walking on the surface, go around the surface of the Moon and throw around these different instruments? Why do it this way?

Chris Culbert: Well, we’ll end up doing both, right?

Host: Oh.

Chris Culbert: But the human systems will take a little longer to get there. We’re hoping to be there by 2024. But there is things we’d like to know about the Moon before we get humans there. And we can utilize both much smaller landers and hopefully, as Camille noted, a more nimble, more agile approach to getting things to the Moon early. And then even after humans get to the Moon, there’ll be a much — there’ll be a wide range of things we’d like to do on the Moon that can’t all be done at the locations where the humans are. So, we’ll get more diverse science and science from different parts of the Moon if we have the ability to take instruments in a lot of different locations. And as Camille noted, the cost is significantly lower than a traditional NASA mission. So, we get more bang for the buck, if you will, by taking advantage of what the commercial landers bring to the table. It won’t replace what the human systems do. They’re still critical for human activities or the opportunity for demonstrations before the humans get there and the ability to land a wide variety of things in a lot of different locations can be done much more cheaply if we partner with industry.

Host: So, Camille, it sounds like —

Camille Alleyne: Can I add —

Host: Go ahead.

Camille Alleyne: Can I add to what Chris said, too?

Host: Of course.

Camille Alleyne: One, Artemis is about human exploration. It’s about humans being able to live on an extraterrestrial planetary surface, which we haven’t done in over, really, 50 years, right? But CLPS allows the science community, right, the international science community — researchers, scientists, astrophysicists, geologists — to be able to send instruments that can help them answer some questions that they still have, not just about the Moon, but there’s so much the Moon teaches us about the evolution of our solar system and the evolution of our whole planet. And so, there is there a lot of unanswered questions within the science community. And CLPS, with our ability to send instruments on behalf of the scientists, allows them to answer those questions.

Host: So, that’s an important mission there, Camille. Can you tell me what the expectations are for the companies that are building these landers to get that science, that important stuff, to the surface of the Moon? What is it exactly that we want these commercial companies to do?

Camille Alleyne: So, we want them — so I’ll back up a little bit.

Host: OK.

Camille Alleyne: We expect them to procure every piece of hardware they need to be able to facilitate the transportation of our instruments, right? So, they have to develop their lander. They have to procure their launch vehicle and any ancillary kind of hardware that they will need in order to accomplish this mission. But we are really, in essence, building a marketplace on the Moon, right? And so, this commercial model facilitates. It really enabled an economy to be built on the Moon where commercial companies can build up their capability and NASA eventually won’t be the only customer that they are servicing. They would have the ability to service many other customers outside of the U.S. government. Other international countries or commercial entities or universities that want to independently send instruments to the surface — they will be able to facilitate that because we have enabled them to develop these capabilities.

Host: Interesting. So, I understand like a lot of these early landers, there’s a lot of NASA payloads in there. I think there’s a few European Space Agency payloads as well. But from what I’m hearing, this can scale to a period where instead of NASA being the customer for these landers, they can expand. This is — I guess the idea here is sustainability?

Chris Culbert: That’s correct. What we’re looking for — NASA would like to be what we call the marginal customer, where we’re just one of many people sending packages to the Moon, so that we only pay a fraction of the infrastructure costs. The FedEx model actually is a very good example. You don’t have to buy a truck every time you want to put your package on a FedEx delivery. That cost is amortized across thousands of payloads. We’re not there with the Moon today, but we’re hoping that if we help get this started, it’ll end up that way and NASA will have the option of being able to take a package. Right now, it’s a — you know, a two-year cycle to get ready to take something to the Moon. We’d like to reach the point where we can say, “Hey, we’ve got a package we’d like on the Moon, you know, next week. Who can take it tomorrow?” That’s where we want to get to.

Host: Express delivery! How about that?

Chris Culbert: That’s right. [Laughter]

Host: Now, Chris, you talked about being intimately involved in building the CLPS effort up. Tell me about how it works. You mentioned something called a task order. You were throwing around contracts. What exactly is the framework here? How does this work?

Chris Culbert: Sure. So, in many ways, CLPS, more than anything — the CLPS project, more than anything, is a contracting vehicle. What we did was we selected, originally, nine companies. Then we added five more who said they were ready. We put them onto the master contract. They have to go through an evaluation process to demonstrate they have the ability to go to the Moon and understand what a lunar mission would look like. Then once we’ve put them on the master contract, they compete with each other. Only the people that are on the contract get to bid on a task order. So, we define our requirements. We say, “Here’s a series of instruments we want taken to this part of the Moon.” We put out a task order, which is a written definition of our requirements. We let the vendors submit proposals, and then we review all those proposals and pick whoever had the best combination of price and capability to meet our requirement. That’s called a task order.

Host: OK. So that’s that framework. Now you did that for — I guess let’s go into what we have so far, the progress so far of what we have asked for, for some of these, I guess, task orders or maybe contract or — yeah, it is task orders — that have been awarded.

Chris Culbert: Yeah.

Host: What was it that we wrote down? What did we say? “Hey, this is what we want. This is where we want to go.”

Camille Alleyne: Sure.

Chris Culbert: Sure. OK. Why don’t —

Camille Alleyne: But for the first one, it was a little different than, actually, how we’ve done subsequent. So, the first task order we call Task Order-2. We awarded two contracts to two companies that will be flying as early as fall of 2021 next year, which is pretty incredible in terms of the time frame. But what we did was we wanted to jumpstart the process, jumpstart the economy. So, we had a buffet of instruments on the shelf, NASA instruments on the shelf, and we said, “We are going to offer you this buffet of instruments because you are just starting out.” And remember, Gary, no one has ever done — no commercial entity has ever done this before. So, we’re really blazing a trail, right? And so, we said, “We have this buffet of instruments. You get to select which instruments work best with the lander you are developing, or you are capable of developing.” So out of those 14 instruments, two of the company — the two that we awarded, selected different ones. One selected, actually — I think ten will be flying on one, Astrobotic, that got an $80 million award, and Intuitive Machines will be flying five, and they got a $77 million award. So that first task order delivery was just jump-starting the economy. Since then, we’ve really focused on the science objectives, right? So, the science community along with Science Mission Directorate did a call for specific science payloads. And the science payloads were selected based on the objectives that the scientists want to meet on the Moon — what they want to study, what they want to research. I talked about the research questions they want to answer. So those instruments were selected in order to start answering those questions. And then that package of instruments we’ll give on — we’ll put on the task order. And so, the companies needed to now show how they were going to meet the requirement of those instruments. And so, since then, we have selected Task Order-19C. Masten Space Systems, a company in California, got an award for about $76 million, $77 million. They will be the first ones going to the South Pole with our science instruments. And then we just selected Astrobotic again, which was one of the companies that got the first award. They got their second award to transport the VIPER Rover [Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover] to the South Pole in 2023. So, to date, really, in the last year and a half, we have been able to award four contracts to jumpstart this lunar exploration science program.

Host: What amazing progress. That’s incredible. That’s — we got a series of landers coming up in the very near future, and I can’t believe the turnaround for Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines going fall of next year. That’s very ambitious and very cool. So, Chris, where are they going? I guess what is — where are they going to be going, and what exactly is the reason for them going to these places?

Chris Culbert: Well, for the first two awards, we let them pick where they wanted to go. And as Camille noted, we’re being — we’re trying very hard to accommodate what the commercial vendors are capable of doing. So rather than telling them where we wanted to go, we said, “You decide which payloads to put in your lander, and you tell us where you’re capable of going.” So Astrobotic is going to Lacus Mortis, which is a large crater on the near side of the Moon, and it’s in the mid-latitudes. It’s an area we haven’t sent humans, but it has some very interesting geology features. And Intuitive Machines is going to Oceanus Procellarum, which is a dark spot we can see on the Moon. Both of those are areas that are mid-latitudes, relatively straightforward to get to. So, for the first demonstration of their capabilities, they’re picking something that makes a lot of sense for what they want to do. As Camille noted, for the next two task orders, we’re starting to focus more on the South Pole, which is where we expect to send humans.

Host: That one I know is a very intriguing spot for the Artemis program, like you’re saying, to send humans. We got these permanently shadowed dark regions that are extremely interesting. And that’ll be, I guess, the — some of the first payloads, some of the first scientific instruments being sent to that region. Very, very exciting. Now you mentioned some — Masten Space Systems in 2022, 2023. Camille, you mentioned a large number of scientific instruments that Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines could choose from, and you use the term “like a buffet” when coming to select some of these instruments. Does that mean that a lot of these were, I guess, already ready to go, and then from there, it was just a matter of the, I guess, respective companies choosing which ones that they wanted to send to these regions that Chris talked about?

Camille Alleyne: That’s exactly right. I mean, we wanted to jumpstart the program, the lunar exploration program, and there wasn’t enough time to go through the process of soliciting instruments, which in and of itself could take a year. And then once you get the instruments, then, you know, you release a task order, which is another set of month process. And so, in order to just jumpstart, as I said, the project, we allowed — you know, we pulled these instruments off the shelf around NASA centers and offered it up to the companies to select which ones were capable with their lander. And these are a combination of spectrometers, magnetometers, a combination of imagers and cameras. So, all of these, again, are very much of interest to the science community to help them, again, start answering some of these questions that they have about the surface of the Moon and really the subsurface of the Moon, right?

Host: There was one that kind of piqued my interest a little bit when you were talking about some of these rovers. The one that’s going a little bit later, it’s something called the VIPER. That one sounded a little bit interesting because I believe it’s a rover. What’s VIPER all about?

Chris Culbert: Right. So, VIPER is a much bigger mission. The original two awards to Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines were both around 50 kilograms. VIPER is going to be closer to 500 kilograms, so, an order of magnitude larger.

Host: Wow.

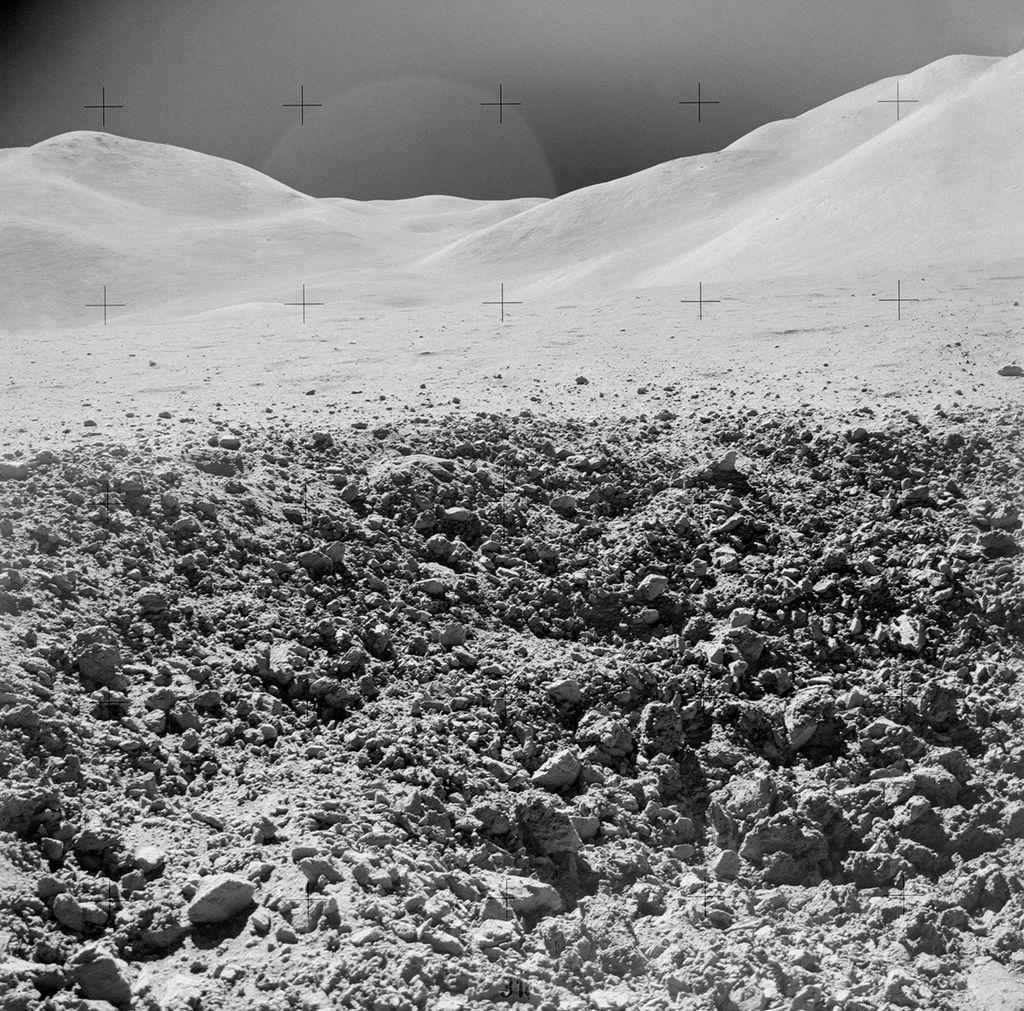

Chris Culbert: And that is a NASA-built rover. We’re building that inside the agency, actually here at Johnson Space Center. It’ll be hosting instruments that come from across the agency, and the biggest one is a drill. So, it’s going to go into permanently shadowed regions, which you can’t really land in. Those are difficult places to land, you know, so you’re going to land someplace where you have sunlight and a little clearer area to land in. And then the rover will drive the instruments down into a permanently shadowed region, drill into the ground to help us understand what kind of volatiles — essentially, water and gasses — might be buried or mixed into the lunar soil. And VIPER will allow us to gather data about those kinds of materials which might be fundamental towards enabling a long-term presence on the Moon because it might enable — might show us where we can find water and oxygen and things that we desperately need for human habitation.

Host: That’s a big mission, and a big engineering challenge, too. I mean, I can’t imagine the difficulty of designing a rover that is going to drive into a permanently shadowed region. That’s a very intense environment for any system, really, to operate in.

Chris Culbert: Yeah. They’re very, very cold. Permanently shadowed regions can be as low as 40 degrees Kelvin, which is, if I remember right, something like minus 400 degrees Fahrenheit.

Host: Not an easy task at all.

Chris Culbert: Yeah, challenging environment.

Host: Yeah. Now let’s go through — I guess we don’t have to go through all of them, but just a few of the interesting things that we’re looking at because I love talking about science on the podcast, and there’s a lot of science coming up in the very near future. Let’s start with Astrobotic. Camille, I’ll go over to you, and let’s investigate just some of the instruments on the Astrobotic lander that’s going to be at — I think it’s Lacus Mortis. I’m sorry if I’m pronouncing that wrong, but some of the instruments going there.

Camille Alleyne: That’s correct. That’s correct. You pronounced it correctly.

Host: Oh, good. [Laughter]

Camille Alleyne: So, there is an instrument called LETS, the Linear Energy Transfer Spectrometer, that’s going to measure the lunar radiation environment. There is another instrument called MSolo, the Mass Spectrometer Observing Lunar Operations, and that will identify the weight of the volatiles that — something akin to what Chris said, except not at the South Pole, but where they’re going, which is a mid-latitude region of the Earth — of the Moon. Another one is the Neutron Spectrometer System, which is indications of water/ice near the lunar surface. So that’s just a sample of three of the several-instrument suite that Astrobotic will be taking with them.

Host: That’s incredible. Now, this is a very exciting time because this’ll be among the first two landers to go to the surface of the Moon in quite some time, and I know scientists have been eager. It sounds like they have a number of instruments that, Camille, as you described, are sort of off the shelf. They’re pretty much ready to go, but they’ve just been waiting for this ride. So, it’s got to be a pretty exciting time coming up here in the near future.

Camille Alleyne: It’s a very exciting time for them, as you said. You know, we have not had a focus on the Moon for quite a while, right? We were focused on the International Space Station and focused on going to an asteroid and ultimately — always our holy grail, right — going to the — going to Mars. And so, the Moon wasn’t quite a priority. And so, scientists now, with this mission, are just, you know, chomping at the bit. Our lunar scientists are so excited and so energized and really, you know, looking forward to future missions. SMD had submitted what we call an RFI, a Request for Information, to the science community, and they got over 200 responses in terms of potential instruments that could be selected for transport missions. So, there’s a lot of enthusiasm in the community around these missions.

Host: Oh, that’s very exciting. Now, Chris, before we go on to some of the future stuff, I did want to investigate just a few items on the Intuitive Machines lander — see what they’re going to be taking to this dark spot on the Moon.

Chris Culbert: Intuitive Machines is going to take a number of other instruments. One’s a good example of additional science. It’s called ROLSES. It’s a low-frequency radio observatory, smaller scale, on the Moon that helps us explore what kind of signals we can get from looking at photoelectrons. But we’re also doing not just science, and the science, of course is very critical to what we’re doing, but we’re also doing technology demonstrations. So, let me talk a little about a couple of experiments that are flying on Intuitive Machines that help us prepare for future human missions. One is called the Lunar Node 1 Navigation Demonstration, or LN-1. It’s something about the size of a CubeSat, a relatively small box, that allows us to demonstrate how autonomous navigation would work. These are the kinds of systems we want to use with the human systems when we take them. Flying them on CLPS in a smaller lander originally gives us a chance to test those technologies and learn how to make them work properly. There’s also a camera system called SCALPSS [Stereo Cameras for Lunar Plume-Surface Studies] which will be looking at — it’ll be taking images, capturing video of the plume. As the lander comes down and the engine’s firing to slow it down right before the landing, we kick up a whole bunch of dust, dust and rocks, from the plume from the engine interacting with the surface terrain. And we want to know more about how those plumes disperse the few — the soil and disperse rocks and whether they can impact our ability to land larger landers. So SCALPSS will give us a chance to capture some data about that that we can factor into designing the human landers when we build them.

Host: Oh, that is very interesting. This is — I guess, Camille, you know, one of the questions I had earlier was, you know, “Why not just do this during the human missions?” It sounds like there’s a lot of technologies here that are part of the CLPS initiative that can actually be applied to the human mission.

Camille Alleyne: That’s correct. The rover, for example, right? We know we’re going to have rovers for the human mission, so that also is a learning experience for us. We are going to eventually have prepositioned hardware for the human missions — communication systems, technology demonstrations, maybe some habitats that, you know, could potentially be flying on CLPS that are prepositioned and there in time for when we have astronauts on the surface.

Host: Very interesting. Now, Chris, there’s — it sounds like there’s just been so much progress in such a short amount of time when you talked about in the 2017, 2018 time frame coming up with the idea for CLPS, and here we are in 2020, and we already have — we have landers for all the way through 2023 at this point to be putting some very important scientific instruments and technology demonstrations, all this great stuff, on the Moon. There’s so much progress already, but I’m sure there’s more. What can we look forward to in the future here for some upcoming task orders and initiatives?

Chris Culbert: Sure. So, we will actually award two more task orders before the end of the fall. One will be another drill. It’s a version of the drill we’re taking on VIPER, but we’re going to take it to the Moon early so we can test it and make sure we understand how the drill works in lunar condition. That will help us prepare for the very important VIPER mission. That’s called Task Order PRIME-1. And then Camille’s working on a task order, which takes the remainder of the instruments we got out of the Science Mission Directorate call last summer to the South Pole along with some technology demonstrations from the science — Space Technology Mission Directorate to gather more data about conditions of the lunar pole. We expect to award both of those by the end of this fall, end of this calendar year. Then we’ll hit a sequence of roughly two task order awards per year guided by the Science Mission Directorate. And then every other year or so, we expect to see other task orders based on either technology demonstrations or preparations for human flights. And maybe Camille can tell us a little about what kinds of things we think those will do.

Camille Alleyne: SMDs are sponsoring CLPS, right? They provide most of the funding for the CLPS contracts. But this is a mechanism for cross-mission directorate participation. So, as Chris said, the Space Technology Mission Directorate, they are already showing interest in flying technology demonstrations, and PRIME-1, as Chris just mentioned, is one of those. They will have some future technologies that they are developing that they would want to send on CLPS missions. And then the human exploration mission in preparation for Artemis, you know, and sustainable human exploration, they will be sending — they will be interested in sending some larger payloads, perhaps some habitat-type hardware, again, pre-positioning for human exploration. And so, there’s a lot of interest across the agency, right, in this project and in this contract mechanism because it just really is flexible, it’s agile, and it allows — it facilitates instruments, everything below human-scaled hardware, to be transported to the Moon.

Host: That is incredibly exciting. Chris, you talked about, you know, possibly two task orders being awarded per year. I can see this really ramping up here, especially when you’re talking about how it folds into Artemis and how, you know, Camille described as jump-starting an economy. Now there’s — you’re — I guess you’re trying to build a larger customer base on the Moon. Can you tell me about, Chris, your vision for what the 2020s are going to look like? Maybe sometime even past this — you know, these first four task orders that you’ve awarded — how you imagine business on the Moon through CLPS.

Chris Culbert: Sure. So, you know, a lot of this is, you know, polishing a crystal ball, obviously, and the one thing we tell everybody to remember is that none of the vendors have demonstrated they can successfully land on the Moon yet. That’s an important first step. We’re very pleased with the progress we’ve seen from the vendors we’ve awarded task orders to so far, but they’ll have to show they can successfully, you know, get you to the Moon and finish that last step, which is pretty critical, of landing softly and safely. But we believe once they’ve done that, there will be interest in science communities, not just within NASA, but outside of NASA as well. We already know that Astrobotic is flying 12 instruments or 12 payloads beyond the ten or 11 that NASA is giving them, and they represent a wide variety of interests. You mentioned the Europeans. There’s a couple of European payloads that Astrobotic is contracted to fly. There are some public interest payloads that Astrobotic is working with media companies and others to work on. So the opportunity to show off a growing economy, which has to be enabled by both commercial vendor success and some evidence that there is interest in things happening, but we’re pretty confident if the price gets low enough — and we’re very pleased with the prices we’re seeing so far — universities might choose to fly a payload as part of a standard university grant process. There are — just like we’re seeing in low-Earth orbit, there are companies whose commercial interests long-term might be facilitated by enabling things to happen on the Moon. If VIPER, for example, is able to demonstrate that there is water buried in the regolith, or the soil on the lunar surface, particularly in the southern pole regions, companies might be interested in getting there to mine the water and then sell it back to NASA or other people visiting the Moon. So, I think there’s a framework for a commercial industry that can emerge. It will depend an awful lot on, again, early success. If the first two landers both, you know, crash on the Moon, that will have a very chilling effect on the economy. But assuming they’re successful, and we think right now that they’re moving in the right direction, we — I think you’ll see a lot of potential interest shown not just in this country, but in other countries that don’t necessarily have the full-strength space program the United States would have.

Host: What an exciting time. This is unbelievable. Now, Camille, adding onto this, Chris described so well the — this economy that we’re trying to build for deep space. What — just, you know, this is a very futuristic concept here, but I know NASA has goals of returning sustainably to the Moon, as you just described, through the Artemis program and then having that inform Mars. So how does CLPS do that for the agency’s overall broader goals?

Camille Alleyne: So, we often say that we are not in the critical part of Artemis, right, that 2024 landing, but we enable the Artemis program by being the trailblazers, as you will, to — you know, to the surface. So that is one way. We are also demonstrating, really, and one of the most innovative private-public partnerships that NASA has ever had. You know, we’ve never done business like this with commercial companies before, where we don’t actually help with the development of their hardware. We’re just buying a service, as we talked about earlier. And so, there’s a lot there that other aspects of Artemis could learn from this particular business model. One other thing I would like to say, though, that we talked a lot about instruments to the surface of the Moon, and that’s primarily the objective of CLPS, but we are also looking at can our commercial companies provide capability to just orbit the lunar orbit, right? Maybe they are CubeSats or other type of communication satellites that need to be put in orbit around the Moon that our commercial companies can take — either transport to orbit solely or transport to orbit on the way to the surface. And so that is another thing you will see coming up in the very near future.

Host: See, Camille, when you say very near future, I just get chills because I just can’t believe what a time, we’re in. You know, this is — we’re talking about the next decade here on just the landscape of the Moon changing entirely. So just talking to you both today, I could just say confidently that this has been a very, very exciting thing to talk about. Chris and Camille, to both of you, I really appreciate your time going through CLPS today, and just what a fascinating concept and project that you’re both working on. I appreciate all you do, and I appreciate your time for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast. Thanks so much.

Chris Culbert: Thanks, Gary.

Camille Alleyne: Thank you, Gary. It’s a blast working on this project, and we’re excited to always share it with the world, so thank you.

[ Music]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. I hope you enjoyed this conversation with Chris Culbert and Camille Alleyne about the CLPS effort, Commercial Lunar Payload Services, as much as I did. We have a few other podcasts here on Houston We Have a Podcast that you can listen to all about the Moon. Just go to NASA.gov/podcast. Click on us at Houston We Have a Podcast. Check out some of our episodes in no particular order. We also have a lot of other podcasts across the whole agency that you can tune into. If you want to learn more about CLPS, you can go to NASA.gov and search in Commercial Lunar Payload Services. There’s also a website for it, NASA.gov/content/commercial-lunar-payload-services. You can talk to us at Houston We Have a Podcast on the Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Just use the hashtag #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea for the show, and make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston We Have a Podcast. This episode was recorded on July 24th, 2020. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, Norah Moran, Belinda Pulido, Jennifer Hernandez, and Rachel Kraft. Thanks again to Chris Culbert and Camille Alleyne for taking the time to come on the show. Give us a rating and some feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of the show. We’ll be back next week.