From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

On Episode 238, Daniel Lockney reviews some of the most fascinating NASA technologies that have made their way into our everyday lives. This episode was recorded on March 11, 2022.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 238, “From Space to You.” I’m Gary Jordan and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, and astronauts all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight and more. One of NASA’s primary goals as an agency is to explore the cosmos, to reveal the unknown for the benefit of humankind. And that benefit can come in a lot of different ways. But I think one of the most direct way is bringing some of the things we learned directly into products and services that we as earthbound citizens use, and can sometimes impact our daily lives. This transfer of technology to the private sector is run by a program called, you guessed it, NASA’s Technology Transfer Program. Longtime listeners may recognize this program from Episode 135. In addition to the work of actually managing the transfer of technology, every year the Technology Transfer Office publishes a book of these technologies that have made their way into different industries. That book is called NASA Spinoff, and they recently published a brand new one for this year, 2022. On this episode we’re talking with Daniel Lockney, Technology Transfer Program executive, about the program itself and about some of the latest and greatest technologies that were included in this most recent publication: things like air purifiers that can make their way into our own homes, or vertical farming technologies that can end up in our grocery store down the street. From space to your own home, here are some incredible technologies, with Daniel Lockney. Enjoy.

Host: Dan Lockney, thanks so much for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast today.

Daniel Lockney: Hey, thanks for having me, looking forward to it.

Host: You have an interesting background, Dan, coming in as the program executive for tech transfer, starting with your, your, your education was in American lit and creative writing. And I wanted to start before we get into just, you know, tech transfer and some of the cool technologies, just how that happened: how, how you went from American lit and creative writing to, to being the program executive of, of this, technology transfer effort at NASA?

Daniel Lockney: Sure. Yeah, it, it isn’t, it isn’t a typical NASA story, really, but yeah, having a creative arts background and then running a, a technical program and being responsible for NASA’s intellectual property portfolio doesn’t, doesn’t really seem to jive. But I’ve been doing this, you know, just about 20 years. And when I, when I got started I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do, but I had interest in storytelling and, but I didn’t have any stories to tell. I was young, and I don’t have anything worth telling. And I, I kind of lucked into this job at NASA as a contractor writing stories about tech transfer, and I found this wealth of material and I just fell in love with it, and that goes back to 20-plus years. And I had originally thought that, that space was something that you’re supposed to outgrow when you became an adult. It was kind of like “Star Wars” or like dinosaurs, and, or playing pirates and that, that you ultimately, space wasn’t serious business, and didn’t have a lot of value here on Earth, right? And you know, I know that sacrilege at NASA, and I, I know I know how wrong I am now, but I always admit that part.

Host: Right.

Daniel Lockney: But when I started working tech transfer, writing these stories, I, I realized there’s this wealth of content, that NASA had so many great examples of, kind of intellectual heroism, solving these challenges for space exploration and for aeronautics missions, and then having all these cool practical terrestrial benefits, and each one was different, and I just fell in love with it. I, I stuck with it and eventually ended up running that thing.

Host: So I wonder that, that period where you fell in love, you must have, you must have interviewed one or maybe several people that just sparked an interest that you didn’t even know was there that made you want to continue it. Earlier in your career, do you recall some of those stories that, that really were some of the, some of the seeds that were planted in you that, that helped you to, to grow so fond of this program?

Daniel Lockney: Yeah, absolutely. So one, one of the things, and I ended up, you know, my, my training in tech transfer is a little bit like the Karate Kid training, where I, I did these routine tasks repeatedly until I developed some mastery over it. And without realizing it, you know, through interviewing, it must have been thousands of people, and writing hundreds of stories about different technologies and tech transfer, and the process of commercialization that, that you know, I built enough of these stories together that I developed an understanding of how tech transfer worked and, and when it worked best, and ended up, you know, serving me pretty well as a program executive for this program. I had, originally getting to meet these folks, these NASA engineers and scientists, and hearing about the work that they were doing was so inspirational. And without giving a specific example, one of the things that I, I fell in love with was, I’ve, I’ve called it kind of like the law, the “Law and Order” format in that with tech transfer and these spinoff stories, they, they follow this kind of typical, routine process. And, and it, it’s kind of like “Law and Order” in the sense that there’s a formula to it, but it’s a really good one. And the characters are interesting, and the stories are compelling, and you could, you can watch thousands of them. And then, you know, I don’t know how many “Law and Order” spinoffs there are at this point and how many episodes, but I know you turn on television and can find “Law and Order” right now. It, it works.

Host: Right? Yeah.

Daniel Lockney: And the same thing is true with these NASA tech transfer stories, and NASA in general: that, that we get asked to do things that have never been done before, solve challenges and, do really cool stuff. So what happens is that the scientists, engineers, programmers get asked to do something and they, they plug along and they’re working and they, they run, run into a challenge where the typical state of the art isn’t sufficient, and they research it, look around and they go, there, there is, nobody’s done this one before. So what we do at, at NASA is we invent something: we solve it, we advance the state of the art. And typically, that takes the form of a new invention, and NASA is one of the most inventive agencies in of all the federal agencies. And if you look at it from a per capita perspective, how small we are, we are easily the most inventive agency. And again, that goes back to doing some things that weren’t done before. So the standard processes, we get asked to do something, and, you know, if we’re taking a “Law and Order” format, you know, there’s that like “dong dong” in “Law and Order,” so there’s the first offense, there’s the crime; in this instance, it’s the mission. Not saying the mission is a crime, just follow the metaphor, right? OK, thanks. So then you end up having to invent something new that hadn’t existed before, and “dong dong” — and let’s say that’s like the detective showing up on the scene – and the metaphor doesn’t track a hundred percent, but the noise is fun, and the, the repeatability of the story is, is the key here.

Host: Can’t argue with that,

Daniel Lockney: Thank you – you’re giving me a lot of latitude here. So then what happens is, we have this invention and it gets reported to the Tech Transfer Office ’cause that’s how NASA does things. And so it goes to one of my offices at the field centers, and we have a Tech Transfer Office at every field center, and our folks look at it and they determine technical viability, commercial viability, IP (intellectual property) ownership, things like that. Export control, you know, is it something we don’t want to tell anyone about? So that kind of thing. So we look at it; if we determine that there is someone else who could use it, we then try to get it out to the public. So then we market it; there’s a handful of different ways, and we can get into that in a minute if it’s of interest, but ultimately we find someone to adopt this technology and turn it into a new product or service. And then, I’ll give you another one: “dong dong,” the story continues. And then at the end of it we have a NASA invention, we have a process by which it got to somebody else, and then we have a new product or service. And the, the starting point and the ending point are rarely ever predictable. Very few times is the end product another spaceship, you know, or a satellite or something. It’s all of these non-aerospace app, it’s generally non-aerospace applications, and consumer goods, and devices that make our life better. And there are hundreds. So when I first started writing these stories, I felt like I kept just discovering more and more of them. And I realized that there was a sea-full of these things. And then NASA’s still doing this. Like every time we get a new mission, this is part of it. If there’s a new invention, of course there is because we’re not being asked to do routine things, you can’t, we’re not getting, you know, told to go do something and then the engineers just go to Target and buy the parts [laughs] or Home Depot – like, this is literally all new, all the time, advancing, you know, the state of the art and, yeah, this is, this unending field of, of potential.

Host: That’s amazing. And so, let’s, let’s go into the, the stories for a bit, because you mentioned, you know, you, you walked us through, through the process of, of the actual tech transfer, how, how that works. You, you’re mentioning writing stories, and so I wanted to dive into that for a second. It’s, it’s part of a publication that, that you guys put out called Spinoff, and part of the reason we’re having this discussion today is because you just recently published the 2022 Spinoff. And so I wonder if you can, I mean, you’ve, you’ve been working in this program for a while, so you’ve done a number Spinoffs, just walk us through what that is and, and how it’s evolved?

Daniel Lockney: Sure. Yeah. So the Spinoff, it, it started off as a report to Congress ’cause Congress, when they, they wrote the Space Act in 1958 that created the agency, they, they had the foresight to, to say — I am paraphrasing law here — but like don’t just blast technology and money into space, make sure that the results of your work come back down to Earth in practical and terrestrial benefits. They wrote that into the Space Act. So, so tech transfer has been one of NASA’s missions since the very beginning, and we’ve been doing this — I’ve lost track of the question, I started answering a different one. Sorry. [Laugher]

Host: That’s, that’s OK. I mean, keep, keep, that, that was good about the tech transfer process and, and why we do it. And then, the, the, the core of the question was the Spinoff magazine, and you said it started as a report to Congress, and then I think, I think it was like the evolution of how a report to Congress became a magazine or, or the Spinoff publication.

Daniel Lockney: Ah, that’s right. Yeah. I started down, I was like, why am I talking about the Space Act? Yeah, I’ll, I’ll do that sometimes. Whenever I give a presentation, I never leave words on the slide because I, I’ll invariably not talk about what I thought I was going to talk about an hour ago whenever I put the slide together. So anyways, so Congress created NASA in 1958. They said make sure that the results you work come back onto the Earth in the form of track, practical and terrestrial benefits. And so, we, we said, yeah, of course that’s a, that’s a responsible thing to do. I, I’ll note also that it’s not, the purpose of space exploration and NASA is not spinoff, is not tech transfer, it’s to advance our understanding the universe and our place in it. And there’s something inherently human about exploration; it’s something that people are going to do anyways and, and that we have been given the privilege of getting to work on that project for humanity is just phenomenal. And one of the cool things about tech transfer is it’s a way to make sure that we’re maximizing the resources and being good steward, stewards of that money and returning as much of the benefit of this work as, as possible. So we started doing this report to Congress in the 1970s. And then, Congress said, you know, this is actually really useful; it’s helpful for me to explain, to, say, a firefighter in my district, why NASA is important. If they say, yeah, this is just rockets, how does this relate to me, and we say, you know, that we developed fireproof materials after the Apollo 1 fire that are now part of your turnout gear; NASA worked with the fire service to help create the first two-way radios that fire departments use. You know, previous to, to this partnership, it used to be that, you know, firefighters would use steel scuba tanks for oxygen, and then what was typically happening is they would, you know, go run into a building and as soon as they’re out of line of sight of the fire captain they would take these heavy tanks off and run up the stairs because you’re not going to run up the stairs with a steel tank on your back. And we helped them develop composite tanks, originally aluminum and now composite tanks, that they use. So a lot of the turnout gear that, that firefighters wear is based on NASA technology and direct tech transfer. So, back to the report to Congress: when Congress would realize that, you know, I could, I could gather support for this work that we want to invest in if I’m able to explain to the public some of the benefits that they’re actually getting from them. So that eventually kind of a, a dry black and white report to Congress, NASA was asked to turn it into something a little snazzier, and we turned it into this full color annual report called Spinoff, which we’ve been publishing continuously since 1976. It’s since gotten a lot more modern, it’s digital, we’ve got a website, spinoff.nasa.gov; we’ve got videos, we’ve got cool celebrity testimonials about how cool NASA tech transfer is, and we’ve got social media sites, of course. And I think the, the, the best product that we’ve created in the past couple of years is actually the Spinoff database. It’s keyword searchable for every spinoff that NASA has developed in the history of our having recorded it. So it’s not necessarily the full number of spinoffs ever, but it’s just everything we, we wrote down everything we could find for 40-plus years, and this is what we got. And it’s all in this keyword searchable database. You can organize it by subject category, you can search by location to see where the different companies are and you find that, that they’re not all where NASA field centers are, but yeah, it’s a really cool tool, the database.

Host: You were, you were part of the development of that tool, right? I mean, Spinoff didn’t, didn’t always have that level of accessibility, you know, maybe folks didn’t have access to, to read the Spinoff publication or, I’m, I’m actually not sure how many people, how many people do. So, so what, what happened to, to start that evolution from, to, to get to that database that you’re talking about?

Daniel Lockney: So, so to answer the second part of your question first, Spinoff is, is actually one of NASA’s most popular websites. It’s kind of an evergreen and NASA’s got some of the most popular websites of all, all the federal government. So Spinoff is, we had a lot of eyes on it, which is all the more reason to make sure it’s not just a print publication that gets distributed to, to a couple libraries around the country.

Host: Right. Yeah.

Daniel Lockney: But in terms of, of developing the tools, one of the ways that I’ve been successful in tech transfer, leading it, has been the development of, of new and simple tools. And I, I don’t have any big secret for how I’ve been doing it, I just, I, it’s, we, we think about what experience we would like to have when we go to a website, look for information, fill out a form. So even our patent licensing, we, we made it much simpler. We, we’ve kind of taken the, the TurboTax approach to a lot of the forms that we have to fill out, that the people, that we ask people to fill out if they want to commercialize their technology. It used to be, gives this dense government form written by lawyers, always kind of complicated and hard to figure out. Instead we ask you some basic questions like, which technology you interested in? What would you like to do with it? We’re the only federal agency currently with its entire intellectual property portfolio searchable online. So it seems strange to brag about creating a website but, but still, we’re number one, we’re the only, we’re the only one to figure out how to do it. And, and it was a lot of work. Every patent, every piece of software we have available for public consumption, is accessible through technology.NASA.gov, keyword searchable, searchable by category. And then we have benefits and applications that, that we think the technology has as well as plain language descriptions of it, links to more information. In some cases, we have videos of the inventor explaining it. So just that kind of — thinking like consumers, as opposed to thinking like government, has really advanced the program. So back to the, the database, we realized, we get asked all the time, so what is, what NASA technologies have benefited agriculture? What NASA technologies have benefited aging studies and research? What NASA technologies have benefited, what, what are the consumer goods that you find every day, or what are, what are the climate technologies that, that are now helping us clean up the planet, and having a quick way to search 40 years of that was, you know, an important tool to develop.

Host: So how did that work out for you? I mean, you’re, like you said, you’re one of the, one of the only federal agencies actually doing this. I’m sure you, this, this database has provided enough accessibility to justify the effort that went into it, meaning that you, you’re, you’re transferring a lot more technology. Have you seen, have you seen more technology transfer since, since you’ve, built this database?

Daniel Lockney: So it, yes, we, the database is part of a suite of tools.

Host: Oh yeah.

Daniel Lockney: And, and I don’t know if, I’ve said the database entirely, but this, this kind of modernization of the program…I’m, I’m, I’ve inherited a 60-year-old program, has been around since 1958; one of the, I still get excited when I find that we’re doing things like paper letters. Very, very rarely, but every now and then we realize, oh, that’s a paper, we can automate that; we, we can, we can make, we can make that electronic. There’s so many simple and fun ways to take this program apart and clean it and put it back together more efficiently. Having a lot of fun with. So, so the database is one of those tools for, you know, it’s handy, if you could search this information, it would make it publicly available. Wow. So in, in the years, past couple of years that we’ve been making these, modernizations, we’ve increased our patent licensing about tenfold, and I had to look this one up, you know, there’s, there’s double, triple, quadruple? Tenfold is decupled. So it sounds like decouple, as in to move something away from something else, but decupled is ten times. That was, that was a fun word to get, to get to look up. And then we, we quintupled, five times, our, our amount of software code that we get out to the public. So there has never been more technology transferred at NASA than just last year. I’ll tell you the previous year was the same, and the year before that was the same. So we, we’ve had this upward trajectory. And I, I honestly, I thought in 2021 that we had, actually 2020 that, that we had hit a number, unsurpassable, we’ll never beat this again. And that the reason was JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) invented a ventilator, right in the middle of the COVID pandemic. There’s that, that Thursday night, when you saw the news: Tom Hanks got sick and they canceled the NBA season? And we’re all like, yeah, I guess, I guess we’ll all go home for a couple days? See y’all in a week or so when this is over. So, while a lot of us, you know, sheltered in place and were like scrubbing, scrubbing our grapes with bleach, there are a handful of inventors out of JPL who said, “respiratory pandemic? [We’re going to work] on ventilators.” So they invented a, I’m calling it simple, comparatively simple, compared to, you know, typical medical ventilators; they created a simple ventilator that had fewer than a hundred parts and key to their design was that none of those parts were required for the supply chain to build other ventilators. They made this new device simple to manufacture, didn’t affect the supply chain, and it worked, and they had it FDA (Food and Drug Administration) cleared. And then we had dozens, close to 40 licenses on it, for companies all around the country, companies all around the world. And the reason we did the licensing and patenting route is we wanted some sort of way to, to suggest that yes, these companies have the real NASA technology and they have the capability to make it. We’ve shown them how to do it, and they have, they have the drawings and the plans, versus you wouldn’t want a situation where, you know, everyone and their brother all of a sudden started saying, I got the NASA ventilator, no I’ve got it. You know, so we wanted to have some sort of traceability so that we could vouch for companies that, yes, we had taught them how to do it and looked at their prototypes and said, yeah, that’s the right design. So this ventilator was used all around the world. Some of our, are manufactured in the U.S., but we’re seeing them, they were particularly useful in Brazil and India where large populations and all folks got sick at once and they didn’t have access to a lot of ventilators.

Host: Amazing. There’s got to be so many examples of, of that, of because I think what’s interesting about technology transfer is just this example, this, this ventilator example that, that you mentioned is, is a, is a NASA technology, it’s NASA people going up and, and thinking up really cool ideas and putting them, you know, giving them out to the world. There’s got to be technologies from NASA that are incorporated into our everyday lives that have wide sweeping applications. And, and, there’s, there’s a couple that we can go over, there’s I think escalators or, or, are one of them, phone cameras; there’s, there’s a lot of stuff that is a, is a NASA technology that is just a wide sweeping impact. And, and folks may not even realize it. And, and you’ve probably seen your fair share of some of these technologies.

Daniel Lockney: So, yeah, the, the conversation usually starts with me saying, Tang, Teflon and VELCRO are not NASA inventions, so that’s what the public thinks. With Tang, John Glenn tasted it and his first orbit of the Earth and say, oh that’s delicious; yeah, man, it’s sugar, it’s orange sugar. It is delicious. Right? Teflon was DuPont and VELCRO ended up being an invention for a Swiss inventor, taking a walk in the woods and some burrs stuck to his pants and got to looking at it, say, hey, maybe there’s a practical application. Those are all inventions that were practical and useful in space, but not NASA invention. So we get credit for those; a tough problem to have, right? That people think that you did things that you didn’t…good things.

Host: Right.

Daniel Lockney: But right. But the, there’s so many heavy hitters that a lot of folks don’t necessarily realize, like you mentioned the cell phone camera: that was, the actual camera that is in your phone right now was developed by an inventor named Eric Fossum out of the Jet Propulsion Lab, Caltech. And he developed a camera on a chip, a CMOS (complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor) sensor. And it’s a lightweight camera that doesn’t use a lot of power, takes a high-resolution image, and is lightweight for, the thinking was you put it on a satellite. All those characteristics are, are valuable and important in that instance. So, we developed this miniature camera. We didn’t know who else could use it, we had no idea. And we thought, we thought spies, right? Or like private investigators. We had all these, you know, cloak and dagger ideas of, of people sneakin’ around with these like miniature cameras and a pen. But that’s not a, that’s not a big consumer market, right? And nobody’s interested. And so, Nokia approached NASA, this is years ago, but, but we still have active patents on it, still our, to this day it’s our camera. And, and yep, all the big companies are paying royalties on it. So Nokia accessed, or contacted NASA and asked if they could have this camera. And we said, yeah, what are you going to use it for? Said they wanted to put it in their cell phone. And we thought that was the most ridiculous thing — who’s ever going to want a camera in your phone? All right. And phone’s for talking, everybody knows that. So yeah, they were, were right. We were wrong. You mentioned the, the escalators; this one I think is just fascinating, but, as part of an energy saving, so again, you can’t run an extension cord up into space, so you plug things in, you need to conserve as much energy as possible. We developed this device at Marshall Space Flight Center, we call it the Nola device. It’s named after a guy named Frank Nola. And it’s a, a piece that you put on an electric motor that adjusts the load, on the amount of energy used by that motor according to the load that’s placed on it. So you’d have an escalator, for example, and the first application outside of NASA was in conveyor belts, but quickly realized that there’s a lot of, a lot of other, uses for that. So, escalators, elevators and moving sidewalks, for example. So how it works is, if you’d have an escalator and no one was on it, it wouldn’t run at full speed. If one person got on it, it would ramp up to lift one person; three people, three people, you get it, then they get off and then it slows back down and uses less energy. So this device is in every escalator, elevator, and moving sidewalk that’s been built since the 1980s. We know this is true ’cause there’s only four companies that make all of these devices. There’s only four manufacturers of elevators, escalators and moving sidewalks, and they all use this device. So when you start picturing every escalator, just, you picture the airport, all those moving sidewalks, you know — in, I say “the” airport, I’m picturing mine, you’re picturing yours; they’re in both of them — so, and everywhere you see an electric motor, they have this device on it now, and just picturing the energy savings, it’s just phenomenal. And then when you’re at the airport, looking out the window, you got airplanes, and it’s got that blended upturned wing, we call that a winglet, you’ve seen that before, you know, if you’ve ever made a paper airplane, which I’m sure you have.

Host: Yeah.

Daniel Lockney: And the, the wings are kind of fold, you fold up the wings on the end and it, it just flies a little better and looks a little cooler. That’s a real thing, so that NASA actually do that with metal, and we tested it, and bending the wings up a little bit allows for significant fuel savings. And so Boeing licenses that from us, you know, 20 years ago, I think the patent is, I think it’s expired by now. And they’ve estimated, you know, tens of billions of gallons of fuel saved just with this adaptation. Yeah. And back on airplanes, you know, people forget that the first A in NASA is aeronautics and, you know, if you’ve ever been on an airplane, you’ve benefited from NASA research. There’s, we’re in every aspect of, of modern airplanes.

Host: Unbelievable. The, I mean, there’s, I, I always love hearing these stories because it just fascinates me, you know, like you mentioned at the top, you know, we’re, we’re exploring space and, and we’re doing all these cool things and we talk about benefits for humanity quite a bit, especially, I work a lot with the International Space Station program and there’s, there’s a lot of research in particular — technology too — and how that benefits Earth tech. This is just, this is just, it’s just so cool to hear about some of these technologies that have such, such broad sweeping effects. Dan, I want to go into the 2022 catalog and some of these new technologies that I think, I think fall into that suit of having broader, or potentially broader, impacts on, on our, our lives. And this is just in the publication of 2022. There’s no format to this conversation, Dan, so if you think of some cool technology that you want to throw out, I am always happy to hear them. But on the subject of the ventilators, because, because you mentioned that technology, and how that helped it with the coronavirus, I, I saw another one in this catalog that was also related to the coronavirus, and it was air purifiers. Very, very good air purifier that is able to scrub bacteria virus from, from the air. And I saw that, I thought that was, that was a pretty cool technology to start with for 2022.

Daniel Lockney: Yeah. People, people took the air quality pretty seriously all of a sudden. [Laughter] We’re very thankful to have good air purifiers. So, yeah, space station research, this, the air purifier that, that spun out of NASA research originally came out of plant growth experiments. And they were used originally to clean ethylene from air in plant growth chambers, and ethylene is the gas that, that plants put off that, hasten their…demise. So, so for example, if you have hard peaches that you bring home from the market and you put them in a paper bag, you trap ethylene in that bag and your peaches will soften up a lot faster than they would just sitting out. Bananas, for example, got a lot of ethylene, so if you put your bananas near your other fruits, the other fruits will ripen more quickly. So in plant growth chambers where we don’t want to have, well we, the chambers, we have that risk of ethylene building up, we want to try to clean that out, we had to develop these air scrubbers. And the same technology that we use for them is now in the public domain, and there’s a handful of different companies that are making these air purifiers based on, this technology. And I’m, I’ve got one in the room I’m sitting in right now that I’m always grateful for. And so, there’s, there’s, so there’s consumer small home ones, but then some of our big devices, and for example, one of the companies that makes this thing called the Airocide air purifier, they had a, last year signed an agreement with the Philadelphia school district to put these devices in every school building in the, in the city. Super cool. I, I, again, you know, then omicron changed everything, so I’m not sure, nobody’s saying, and definitely NASA’s not saying that these things are going to prevent you from getting the coronavirus.

Host: True.

Daniel Lockney: However, the thought of having clean air in a classroom is, is pretty cool.

Host: Yeah. That seems to be a pretty common theme. I’m, I’m, I’m thinking about this, Dan, based on some of the technologies you’ve pointed out, the air purifiers were, were one of them, and then the cameras, that, that goes into cell phones was, was another one. The theme seems to be that NASA encounters some, some challenge that they, they need to go solve. And so, for the case of the camera, for the case of the air purifier, there was like one small aspect for the camera, it was like a, they needed to make the device smaller to put it on a spacecraft because they needed to reduce weight, and so they did it. And, same with air purifiers. They needed to do something very specific to a, to a plant growth experiment. But the idea here is, it sounds like you guys in the Tech Transfer Office are, are taking some of these technologies that are, that are invented for very specific space purposes, and then you have, like, it’s just a, it’s fascinating to me, the creative jump that goes from a space technology to the way that it is applied on Earth. And, and they’re, they’re applied so broadly, like the, the camera, for example, I’m looking at my phone right now with a tiny camera in it; it’s just, it’s, it’s, it’s just fascinating to me that that started with an idea that was for such a very specific purpose.

Daniel Lockney: Yeah, man, it it’s as good as “Law and Order,” right? [laughter]

Host: Yeah…”dong dong.” [Laughter]

Daniel Lockney: We, “dong dong,” right? When you mentioned the space station, my mind went to, to one of my favorites and just, just ’cause it’s simple and is kind of fun to think about, you know, exercise on the space station is a treadmill, and if you’re going to try to run on a treadmill in microgravity you’re going to float right off. So, so typically what they’ve done in the past was they would use bungees and kind of just strap you down. That’s not the most comfortable, it’s probably not the most precise, either. So we developed this, this bladder system; I picture like one of those like, like swimmy things that a kid would sit in in the pool, like a donut. So we developed one of those…right, you picture it; doesn’t have the swan on the front of it or anything, but it —

Host: The one, the one I’m picturing has a swan.

Daniel Lockney: Me too, but we shouldn’t. So in this instance, it’s this, like kind of an inflatable waist, and you dial in the air pressure according to your weight and it puts just the right amount of pressure on you to push you down into the treadmill to replicate gravity. So pretty cool. How it’s used on Earth is, and this is just the fun kind of simplicity of this story, is how it’s used on Earth: we flip that upside down and instead of pushing people down on the treadmill, we lift them off of it. And where that becomes useful is in injury recovery. So let’s say you got a, well, an injury, and, but you still need to get some exercise and work on your mobility. You, you can offload some of the weight that you would normally be pushing down, just of your own weight, as you’re doing this exercise, so as to continue to exercise without putting more stress on your, on your injury. So physical therapists are using this thing, it’s great for bariatric patients, it’s great for sports injuries, recovery in general. So this thing started to pop up in physical therapists office here and there, and then sports teams caught on: it can also be used for speed training that if you could, kind of, kind of like, a picture like, like the cartoons where you start running but your feet aren’t touching the ground yet, but then when you hit the ground, you take off.

Host: Yeah.

Daniel Lockney: So for speed training, one of the techniques was to try to train your legs to go faster than they’re used to. And so, typically what you do is you run down a hill because you can run faster because there’s, there’s, you’re just running down a hill. But then you got to get back up at the top of that, that’s no fun. So for this type of, you know, kind of, getting your legs to move faster than they typically would or could, you can use this device to lift the athlete up a little bit, take a little bit of the weight off, and train their legs to, to, to register that faster movement, and then ultimately to, to faster running. So NFL (National Football League) teams adopted this thing and other sports teams adopted this thing, and the next thing you know enough people are buying it that the price goes down, but now you’re seeing it in physical therapist’s offices all around the country. And it’s now ubiquitous: it’s called the AlterG treadmill. And there’s, there’s one within 50 miles of you if you’re listening to this podcast. Super cool.

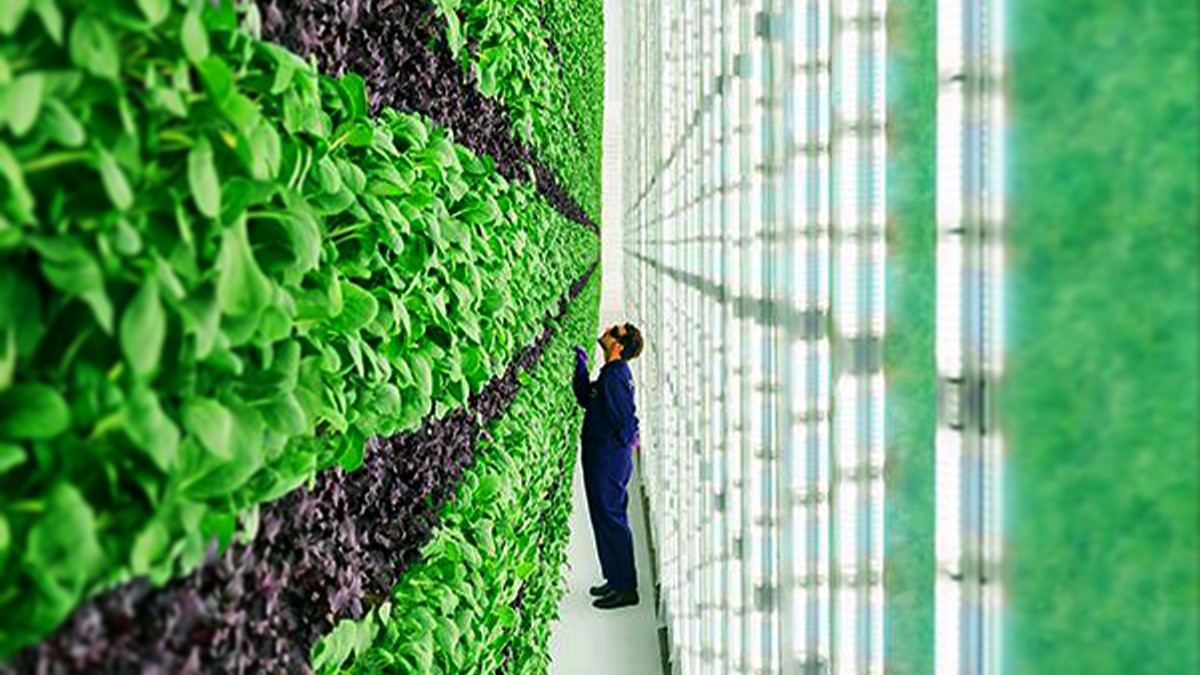

Host: Very, oh, that’s so cool. That it’s that, yeah, it, it’s that scaling up, right? The idea that as it scales up, it becomes more, more widely distributed. I, I found another one in the ’22, 2022 catalog that I thought it, it could fit that mold. It was, it was, it was better technologies to, to make vertical farming more efficient. And I picked out this one because I was thinking, you know, some of the things that are grown in vertical farms in, in the same vein and the same idea, could end up in your grocery store. So what was this, this technology on vertical farming?

Daniel Lockney: So this is decades of NASA research into figuring out how to grow plants in space, with as little footprint as possible, as little weight as possible. So just, you’re not running an umbilical cord up into space, you’re also not, you know, shipping a, you know, terracotta pot full of soil and a watering can and a couple tomato seeds. You’ve got to find the most, most efficient way, you put it next to the window, right, with day, day changing every 90 minutes. No plant’s not going to put up with that. So we developed ways to grow plants with, with lightweight growing medium. So even lighter than hydroponics or soil; we use a nutrient film on the roots. And then we can dial the lights in just right, and we can scrub the ethylene from the air, and we can put enough sensors in there that, that we can check on the needs of the plant and see if it’s experiencing stress and adjust the light accordingly and the, or the water accordingly, or the nutrients accordingly, so that you end up not needing pesticides, you end up not needing fertilizers, you’re, you’re doing it all that naturally – well, in the sense that you’re adjusting light, and, and the water and, and the, the nutrient. So you’ve got this kind of super-efficient growth chamber with a small weight and small footprint. So one of the things we started doing was at, at Kennedy Space Center was trying to see if we could, you know, build walls of these things. So vertical farms of these ultra-efficient vegetable gardens. And we did, and we published this information and, you know, shared it broadly and freely with anyone who was interested. And now there’s a couple companies that have, you know, adopted the NASA, NASA methods in our producing crops. And the cool thing is, as the world gets denser and denser, and urban areas keep getting denser, one of the things that you don’t have in places packed full of people are big empty fields. You know, they just don’t go hand in hand. So, so finding ways to grow crops in dense, urban areas, nutritious crops that don’t, you know, aren’t all covered in pesticides and fertilizers, is a, a valuable thing to do. So there’s a couple companies now, in urban areas around the country, where these things are producing crops that you’ll actually find in grocery stores. Like, there’s a company up in New York that’s creating lettuces that are now being sold in all the New York-area Whole Foods. So you wouldn’t even know it, walking into the grocery store and you, know, that lettuce looks OK, and you buy it, you eat it — it’s NASA lettuce grown in a, on a vertical farm, never touched dirt.

Host: Amazing, amazing. I got, I got one more, Dan that I pulled out from, from this, 2022. I mean, actually I have a lot more, but I, I did want to pull out one that I thought was on this theme of having very, you know, very wide, very sweeping effects, because I’m looking at my phone and I’m thinking about that camera. One that I saw in the 2022 catalog was improved battery testing. And I thought that this was, this was good because you know, a lot of us remember the time where lithium-ion batteries were, were catching on fire, and so, you know, a lot of us started thinking about safety, safety in battery. And I think this one, this one I think is, is a good one for, for that wide sweeping applications of, of things like batteries.

Daniel Lockney: Yeah. And this one’s a real simple story, too, in that batteries used to catch on fire. And lithium-ion batteries were, were powerful and fast charging and, and much more advanced than anything we’d had before, but they would light on fire sometimes. And, and NASA didn’t want that. We definitely, fire’s very bad in a space environment especially. So we started testing them and developed new protocols and methods for testing lithium-ion batteries that are now industry standard for ensuring that they aren’t going to light on fire. So now if you got lithium-ion battery, and thankfully it’s not bursting into flames right now, that’s, that’s NASA research that’s been shared widely with industry.

Host: I love that.

Daniel Lockney: I’m, I’m thinking of plants again. And this is just the plant growth experiment. This is, it’s kind of an older one, but it, it takes a while for these technologies to become – and this wasn’t even seem like technology; knowledge – to become ubiquitous. And, you know, something like the cell phone camera, it took 20, 15-20 years before all of a sudden we all had them everywhere. But I’m thinking back to something that happened in the 1970s, there was a researcher at Stennis Space Center named Bill Wolverton. And, we were building this, kind of simulation of a space station, and it was a, essentially a, a mobile home, that we fitted out to look and act like a space station. We would experiment with, you know, locations of things, living in it, just a, a simulator. And one of the things that people noticed when this thing first got built was, you’d walk in and your eyes would sting. And it would, it was just kind of like a, like a funky chemical odor to it, and people get headaches and not want to be in there. It’s what we know now is sick building syndrome. If you ever walked into a new building, new construction, and they’ve put, you know, the formaldehyde and the glue and the carpeting and the paint is, is off-gassing; nasty chemicals. And you kind of walk into like a, like new, dense, sealed construction: old houses breathe a little bit more, but this new, new construction with all inorganic materials off-gassing, will give you a headache pretty fast, and it’s not good for you. So we experienced that in, in this…called the BioHome at Stennis that we built, and so Bill Wolverton said, you, you know what cleans the air? Plants. And everyone said, Bill, that’s a, a, that’s an old fairytale; plants don’t clean the air…he said, I think they do; I think they do. So he started experimenting with plants and determined and established that plants do clean the air. So, now you and I know you have plants clean the air, right? Common, common knowledge. So NASA proved it.

Host: Right. Yeah.

Daniel Lockney: That was Bill Wolverton out of Mississippi, in the 1970s. Yes, it’s true. So Bill tested it and validated it. He also determined, kind of interestingly, that it’s not the leaves that clean the air, it’s actually the root system that traps all the contaminants. That was the neat little aside. So the reason I, I bring this up is, one other kind of “no fooling” moment. So Bill needed to get his hands on as many different plants as he could in order to test them to see which ones clean the air the best. So we reached out to this kind of newly formed industry group, group, this consumer houseplant association, and said, can you all send me a bunch of plants? I’m going to test them. And they said, yeah, OK. So they sent Bill a bunch of houseplants and he tested them, and he tested hundreds of different plants and came up with, you know, 10, 15 that did the best job of cleaning the air. And they were things like, pothos, the snake plant, Norfolk pine, philodendron, rhododendron, all of these plant names that you’ve heard of, because after Bill’s research into which plants clean the air the best, the houseplant society started promoting it and saying these are the plants that clean the air the best. And those are the ones that got propagated, grown and sold in the country for the past 40, 50 years. So the reason you go, when you go to the store and you pick up a houseplant and it’s a pothos or rhododendron or philodendron or an English ivy or a Norfolk pine or one, one of these common houseplants, it’s because the NASA research showed 50 years ago that those are among the best at cleaning in the air.

Host: Oh, that is wild, that’s why we have the houseplants that, that we have.

Daniel Lockney: [Laughter] Isn’t that weird? The other thing, so my wife gets so sick of this: we’ll be walking along, moving down the street and I’ll point to something and say, do you know about that, and she says “Is it NASA?” “Uh, yeah.” [Laughter] Sometimes I say no, but it is, it, it always is. There’s so much NASA everywhere you look.

Host: And that’s, I, I think that’s a, that’s, that’s a, I’ll end with a question like that, Dan, is, that, that, that seems so important, me and you are laughing, it’s just because it’s just, it’s surprising, it’s, it’s, we’re, we’re in awe about thinking about just how, how fascinating this is, but ending on, on reflecting on just how, how this, how this, how NASA research is important and this tech transfer capability to bring it into our own lives is important, you probably better than anyone have seen the benefits of, of exploring the cosmos and how that, that transfer happens to, to our, to our daily lives. From, from your perspective, why, why is exploration so, so important and, and, and what are, when you, when you go out and tell people what are the benefits, what are some of the things that, that you leave people with?

Daniel Lockney: So I, again I, I think that it’s important to emphasize that, you know, tech transfer and spinoff, and these advances in our everybody life, that they’re gravy. They’re nice additions to get as a result of this work that we’re doing. And they’re cool and they’re everywhere and they make us safer. They save lives, you know — implantable heart devices, the ventilators, defibrillator components, you name it. That also helps the economy, you know, creates jobs and increases revenue and increases domestic manufacturing. There’s, there’s a lot that goes into this, but ultimately it’s all about being human and the kind of core need of humans to know what’s beyond that next hill. And for us that’s space. And I, I think it’s just cool that humans are always explorers. And I, and I, I think it’s kind of intrinsic to who we are as a species, and it means we get cool stuff like cell phone cameras as a result of it.

Host: Amazing, amazing. Dan Lockney, thank you so much for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast, sharing some of these incredible stories, incredible technologies; very much appreciate your time. Thank you very much.

Daniel Lockney: Hey, thanks for having me. This is fun.

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. I hope you learned something today and got excited about a lot of the cool technologies that are coming out of technology transfer. Check out spinoff.nasa.gov to check out their latest magazine, Spinoff 2022. You can also check their database for any story of any in, any kind of technology that may be of interest to you. And of, of course, if you’re in the industry of actually wanting to use some of these technologies, like Daniel said, they can walk you through the process at that website. We’ve talked about technology transfer before on this podcast, and you can check out Episode 135 on our list of episodes. And of course, you can check out any of our episodes, in no particular order, at NASA.gov/podcasts. There’s also a couple of other shows there that you can check out at your convenience as well. If you want to talk to us, Houston We Have a Podcast, we are on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. You can use the hashtag #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea or ask a question, and just make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston We Have a Podcast. This episode was recorded on March 11th, 2022. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, Heidi Lavelle, Belinda Pulido, and Greg Wiseman for their role in making this podcast possible, and to Nicole Rose and the space station program research office for coordinating the topic items. And of course, thanks again to Dan Lockney for taking the time to come on the show. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.