“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

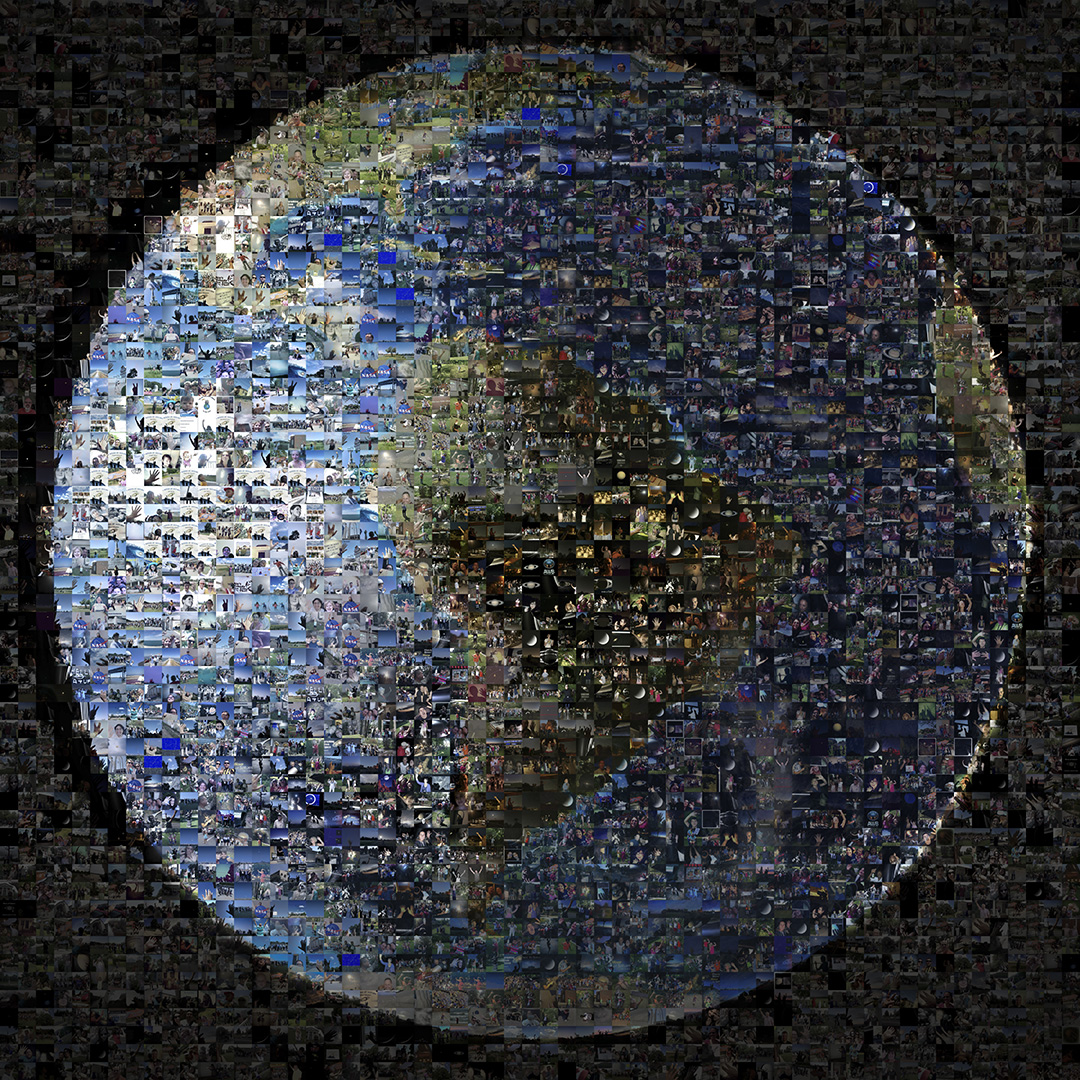

On Episode 97 Lynn Buquo and Steve Rader discuss how NASA is using crowdsourcing as a way to support research and development efforts by tapping into the expertise of global communities to create innovative, efficient and optimal solutions for real world challenges. This podcast was recorded April 2, 2019.

For more information about NASA’s crowdsourcing initiative check out the Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation webpage!

Transcript

Pat Ryan (Host): Houston We Have a Podcast. Welcome to the Official Podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center. Episode 97, Crowdsourcing. I’m Pat Ryan. On this podcast we talk with scientists and engineers, astronauts and lots of other folks about their part in America’s Space Exploration Program. And that includes some parts of the space program that you might not think of right away. I think it was an episode of the Mary Tyler Moore Show or some classic like that, in which some dopey character asked the people who put together a television newscast, “Where do you get your ideas from?” No really. Of course in their case the ideas come from real life, from the news. But what if you’re not reporting what other people have done? What if you’re doing things that are brand new? Where do you get your ideas from? At NASA the people who come up with amazing ideas for the things that we do are also smart enough to know that they don’t have all the answers, or even all the best answers. And for some years now, the agency has been making an active effort all over NASA and the rest of the government, and everywhere else to ask the question which I happen to know is critical to TV producers the world over. I don’t know, what do you think? NASA’s Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation was established in 2011 to pursue crowdsourcing as a way to support research and development efforts. Its website says the team works with innovators across NASA and the federal government to generate ideas and solve important problems. And that they’re trying to create innovative, efficient and optimal solutions for real world challenges by asking other people, by tapping into the expertise of the global communities. Today we’re going to find out about NASA’s crowdsourcing initiative and the good ideas that it’s already brought into the agency. Our guests are Lynn Buquo and Steve Rader, the Manager and Deputy Manager respectively, of the Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation here at the Johnson Space Center. And heads up, when you here them say CoECI, they’re pronouncing the acronym for their office name, which in this case is a whole lot easier than repeating that name every time. Okay, here we go.

[ Music ]

Host:I guess it’s a whole high school debater in me that wants to start by making sure we all know what we’re talking about. So let’s define the terms. Lynn Buquo, what is crowdsourcing?

Lynn Buquo:Oh I set this up so Steve could actually be the one to define crowdsourcing.

Host:You are the boss.

Lynn Buquo:Because – because I think the passion that comes with what we’re doing is best. It comes through when he talks about it; so I thought we’d let Steve start with the definition of crowdsourcing if that works for you?

Host:That’s fine. Steve?

Steve Rader:Sure, yeah.

Host:You better get this right.

Steve Rader:Yeah we use the word crowdsourcing and we use the words open innovation to talk about really opening up beyond your normal team, your normal set of folks. And that can be opening up to a crowd like NASA at work, that is all the employees at NASA. Or, it can be a worldwide crowd of you know, 32 million like Freelancer.com. And crowdsourcing is really any time you get something from a whole group of people, whether that’s from individual inputs or little bits of work or lots of work, or teams. People really have seen crowdsourcing at work with stuff like Wikipedia, right?

Host:Okay.

Steve Rader:That’s where lots of people made lots of inputs and through a process that got vetted and now it’s one of the – the premier places for people to go for information on the planet, right? There’s a great book by Clay Shirky called “Cognitive Surplus.” And it talks about how many cycles the humans have, spare cycles. Especially with the advent of the 40 hour work week. And we don’t think about it because a lot of people just watch TV and whatnot.

Host:What do you mean by spare cycles?

Steve Rader:Spare cycles, when you are awake and you are able to do stuff, and you’re not at work, and your brain can be put to some use. And in fact, we talked about it’s a great example, no one bats an eyelid if you go to five hours of NFL football and spend your afternoon that way. But people will look at you funny if you say yes, but five hours working on this really hard technical problem or creating a CAD model or working on Wikipedia writing up some solutions, but people have a real passion for making a difference and for making an impact. And a lot of people have different little niche passions that they go after online. And they connect with people they know enjoy that same thing, or have that same passion. They do that to learn, they do that to contribute. And so you get – you end up with communities like Topcoder, which is 1.5 million software developers and data scientists that all come together to learn and to have competitions and to connect with people that have that similar passion. And we can name five others, 100,000 people at Tongal, all about video and doing video contest and connecting on how to become a filmmaker.

Lynn Buquo:You can think about it in terms of the people who have passion for NASA as well, all facilitated by the internet, right? How many people spend time on the NASA website looking for information, right? It’s really a similar principle, and one of the things we’ve talked about is we’ve been really fortunate. People want to support NASA. I mean worldwide, we’ve had people that one, are passionate about the mission. We keep using the word passion here. They’re passionate about the mission, right? And they want to participate. They want to figure out how they can participate. And I think that’s one of the things we’ve been really fortunate because we work with lots of government agencies who are doing – using crowdsourcing as a tool to help them advance their mission, right? And we’ve been really fortunate. The NASA brand is a really powerful –

Host:Oh sure –

Lynn Buquo:Powerful brand in and of itself.

Host:Is this relatively new in terms of years where you are finding people willing to contribute to places where they don’t work, and they’re not being paid?

Steve Rader:Yes and no, right? So crowdsourcing and challenges has been around for hundreds of years, right? The big contest back in the 1600’s to come up with a clock that would let you sail from east to west and things like. The famous cabinetmaker that won that, that was not the normal scientist. Those kind of things have been around a long time. The real difference is these platforms, right? These ability – the internet and its ability to connect people in ways that you can do this on a scale and a regularity. And these are really a two-sided network, right? One side is downward facing to the actual community and building that community, and trying to bring them together around doing stuff. The other side often will face as a business, so Topcoder supplies software services and they can build software for you, and InnoCentive solves really hard problems for companies that they can’t solve any other way. You know dongle produces videos. And so there’s two-sided networks and the platforms that they have sometimes will use machine learning to match people with tasks, sometimes they’ll have really elaborate ways to do these contests, to give people incentives. Top coder you can actually get scores by the work you do on there, and you can work that score up. I think data scientist that has a 2800 or above, can literally walk into Facebook or Google and get a job – works as a resume, yeah.

Host:My question what does the score get you?

Steve Rader:Right, yeah and that’s what we’ve seen. We’ve actually had people we know that have worked with us on projects that tell us; hey I’m leaving early from the project because I just got a job at Google.

Lynn Buquo:NASA itself actually started using crowdsourcing in 2005. When we got the Centennial Challenge Program. And if you think about it I had an attorney teach me once, because the question of what is different about crowdsourcing and the government, because what he trained me to realize is that in the private sector you want to go do the thing. You should be asking the question is the thing I want to do legal? In the government when we want to go do a thing we have to question is there a law that allows us to go do that thing? It really put in context for me the difference between working in the private sector and working within the government. And for us what we have figured out is that we have several laws, several legal authorities that actually allow us to do crowdsourcing. Centennial was the first within the Federal Government because people were seeing things like the Exprise going on. And so they looked to which agency would be the best agency for us to think about what – who could use this tool best. And of course NASA was selected. So in 2005 they actually added to the space act, this ability for us to go do these big public multi-year, multi-million dollar challenges. And kind of the way it’s evolved is what we’re about is not those big challenges so much, although we’re supporting other agencies with them right now. But really about using crowdsourcing as a smart way to do a government procurement.

Host:A procurement is when the government decides I need a thing, I would need to acquire it, I want to buy it but I can’t simply go buy it.

Lynn Buquo:Right.

Host:It becomes much more complicated.

Steve Rader:Exactly. And there’s a real thing going on here. In fact we’ve just been putting a story together about this. The – times have changed significantly over the last I’d say 20 years. Technology has just exploded and a lot of that is due to these building block technologies like open API’s, like Google Map API, right? That’s one where when they came out with it and suddenly people could use that, 50 different applications suddenly popped out of nowhere and now you have Waze and all sorts of different applications that use it. And that’s repeated over and over with Nano coding’s and with crisper in the bio-tech area. And with different sensor, new cheap sensor technologies. And these building blocks apply across all different domains. So people actually use crisper, which is for DNA sequencing and editing the genome. But that’s being applied over here in petro chem and it’s being applied over here in various other industries for coding’s and industrial processes. So, we’re seeing that over and over. And it’s been an explosion. If you look at the number of patents that have come out over the last 20 years. You see this big exponential curve, and in fact there’s a stat out right now, that kind of characterizes it, which is 90% of all scientists that have ever lived are alive and working today.

Host:Oh okay.

Steve Rader:And so when I first came to NASA if you wanted to get the latest and greatest technology to go build on, you had to go check out a few tech journals, go to a conference, talk to a few vendors. And you knew you had whatever the latest and greatest thing was. That is now almost impossible to do. You can’t just go look it up. You can’t go Google it because a lot of these companies are keeping that stuff close until it’s actually for sale. It’s happening in universities and industry all over the world. And it’s happening at a scale that’s just unfathomable to our traditional means. And so this new way of actually having to find the valuable technologies to go build on and invest in right? Once you pick it, you go spend millions of dollars. You don’t want to find out three years into that and 10 million dollars later –

Host:That it doesn’t work.

Steve Rader:That it doesn’t work. It’s a very expensive thing. And what we’re finding is the crowd is actually the best way to go find that needle in a haystack. Because the crowd happens to be a human network that’s connected to almost every corner of the technical world. And so crowdsourcing challenges end up being this kind of new quirky thing in a lot of people’s minds. But it’s exactly what’s necessary in the new world order for technology.

Host:And to reinforce something that you said before, it’s that development of technology over the last 20 years that’s allowed the crowd to be involved.

Steve Rader:Exactly.

Host:That allows me to sit at my desk and click a button and find out maybe what NASA’s looking for but anybody else, find out what those things are.

Steve Rader:And it feeds on each other, right? It’s this loop where the crowd gets bigger, they learn more and we get more technology built up. And we’re seeing big leaps happening, right? So we’ll do challenges and we can show where the performance of an algorithm is 120X improvement, not just like a 10% improvement. And it’s because we’re getting this diversity of thought and diverse expertise applied to problems.

Host:Before we do that, let me get you to tell me more about how it started for NASA. You mentioned a – and help define the words challenge. What is a challenge in this sense?

Lynn Buquo:Yes. So for us what it means is we – public competition. We have a problem, we put it out there, usually through a website and it says we need a solution to such. And people actually submit solutions and compete for an award or a prize based on the authority we have different terminology for what. But it’s really about a public competition that people can participate in at their computers, at their desk. Now some of the centennial challenges actually have people show up and do tech demonstrations. We just did our first that we manage kind of tech demonstration type public competition that down selected and the people brought their prototypes to the Glen Research Center to have their technology actually tested at the Glen Research Center. So a challenge, a competition, those are – we use those terms interchangeably actually.

Host:And if people are competing for a prize, is that a money prize or could it be some other kind of thing? Something that you’ve decided they will find to be of value?

Lynn Buquo:So NASA itself has a whole range of public challenges. The space apps challenge, the world’s biggest hackathon. There’s no prize money that people get for participating in that. They get to win the people’s choice award.

Host:They get probation of their peers.

Lynn Buquo:That’s exactly and a lot of people that’s what they’re looking for, is recognition. There’s the old goal, guts and glory.

Host: And good.

Lynn Buquo: And good. Goal, guts, glory and good.

Host:Four G’s.

Lynn Buquo:Yes, the four G’s and it varies. Because we’re buying something through the use of crowdsourcing, we always have funding associated with that. So people compete, the value of the award is different. It changes based on how complex the problem is. One of the things that we figured out by working with Harvard, because we have this relationship that was developed with Harvard back in 2009, 2010. When we were first looking at using crowdsourcing as a way of buying stuff. They really helped us figure out that the – the amount of the money isn’t the real incentive for participating a lot of the time, so it was one of the key things that we got from their research.

Host:So you didn’t have to overprice it –

Lynn Buquo:More money doesn’t necessarily mean – yeah more –

Steve Rader:And in fact you can overprice it to where the prize is too large according to their studies, will drive the very people you need away. They’ll think it’s too hard.

Host:I can’t possibly do that.

Steve Rader:Yeah, yeah.

Lynn Buquo:Right. If they’re giving that much money.

Steve Rader:We, our office the CoECI and the NASA terminal, we particularly use what we call curated crowds, which are these companies that have actually pulled together communities around a passion, around particular area

Host:Private companies.

Lynn Buquo:Private companies.

Steve Rader:And they have brought people in voluntary, it’s free to join these communities. But they built them up to where they know what incentivizes them and they know like I said Topcoder, you can get these points, you get badges, you get – and other ones you might get recognition on their site and different ways. And they know how to set the price for what you’re asking for. And they have ways of licensing or transferring the intellectual property. To have all of that kind of worked out with the crowd. And so it’s just normally business and we use that to get different –

Lynn Buquo:At this point in the podcast I think it’s necessary to state that we are not endorsing any of these – we have contracts with them and so we have legal mechanisms that we work with these companies. These are not – these are not endorsements.

Host: Yes. In the –

Lynn Buquo:I just had to say that.

Steve Rader:Well we have – we work with 16 different crowds. And I added it up the other day. I think it comes to something like 70 million people we have access –

Host:Participating –

Steve Rader:Through these platforms.

Host:Through one or more of these other companies.

Steve Rader:Right we can access just millions of people and really if you get a good tweet out on NASA Twitter account you can actually draw even more people in because they’re free to join.

Lynn Buquo:Who come and join those communities.

Host:Because they’re following NASA on Twitter, but weren’t already involved in one of these companies.

Lynn Buquo:Right right.

Host:To go back to one of the original – the original challenge – give me a sense of what the guts of this was about? What was NASA trying to get and decided to issue this challenge to acquire?

Lynn Buquo:Oh to use – to figure out how to use crowdsourcing as a way to actually get –

Host:Back at the beginning what was it that we were after?

Lynn Buquo:So the centennial challenges program was really about stimulating innovation in the private sector. That in the long term would end up helping us. When it was actually Jeff Davis here at the Johnson Space Center who was attending a class at Harvard, a management because our senior executives get trained well, right? Was attending a class and he heard about this open innovation use of crowd sourcing that was happening in the private sector. And by the way this is very, very common in the private sector. We probably are about 10 years behind in terms of really taking advantage of it, maybe even longer. But what he learned was hey, there’s this whole new way that we could actually go and acquire R & D. We could actually use this as a way to do that. And he had just taken a huge budget cut in his organization. So he comes back, he was aware that we had this centennial challenge stuff going on. But he was looking at shorter term, faster; let’s acquire these – this R & D if you will. And so ran this pilot to see whether or not it would work. He looked at the human risks that were most important to his organization at the time, what were they looking to minimize in terms of the risk of human being, being in flight, in space. And then from that derived kind of these are the things that would be really big wins if we could go solve these. And so we put in place a mechanism with an incentive to do some external competitions. Our first look at it. Thanks to our very smart lawyers who said by the way we couldn’t use the centennial authority that was given to us. But they looked at the federal acquisition regulation and said this is no different than how we do business all the time. We have companies that we contract with. We say the government has a requirement for a new way to wrap space food. And that company just happens to go develop that solution to that particular problem by launching a public competition.

Host:It fills – to fill the order.

Lynn Buquo:It’s to fill the order. We don’t care how they do it. They happen to go launch a competition and they bring us back. Here’s the best things we got from this, government evaluate these, which one fits the bill. And then we get our solution and they pay the prize amount. We don’t pay the prize. It’s the contractor who pays the prize in our particular – in a NASA Tournament Lab competition. We have to be very careful about that because these are technically our contractor’s competitions. NASA is definitely involved, NASA is requirements owner. NASA is working hand in hand with them, but it’s technically their responsibility to deliver a solution. So we did this. We did this in a pilot foreman, it was like wow, this could work great. This could work great for us. We not only piloted external competitions, we piloted the use of competitions with the NASA community at large and that’s how NASA at work was born. Because I think very early on one of the things we realized is this agency has incredibly talent, has incredible skill, has incredible knowledge. Why don’t we try and figure out a way to share that across the agency.

Host:That’s scattered all over the country.

Lynn Buquo:All over the country. And everybody at NASA is busy doing their job, head down doing their job. If they have a little bit of this cognitive surplus to dedicate to solving somebody else’s issue over at the Johnson Space Center then people at Marshal will get on. We don’t ask them to spend a lot of time. That was piloted. That was incredibly successful as well. So after that, that was just kind of a test case. We then had to go up and do full up procurements to bring contracts on board to continue to exercise this. So early on back in 2012 we had relationship with Harvard Topcoder, relationship with InnoCentive, relationship with a company called yet2.com and then in 2015 we moved – we realized there were more companies, people doing this as a business model is not getting less.

Host: Really?

Lynn Buquo:There are more and more companies that realize this methodology works. This is a solid business model for them. So, in 2015 we put in place a mechanism where we now have contracts with 10 companies who specialize in crowdsourcing. Not only that, Steve went and did a pilot to see, hey there’s all these low cost platforms that are popping up to do this stuff. We do these same things with the government credit card. So we have micro purchase challenge that –

Host:We like low cost.

Lynn Buquo:We like low cost, with tremendous results, right?

Steve Rader:Oh yeah, we were able to do in that pilot I think 14 CAD challenges that normally would have cost a thousand –

Lynn Buquo:In the credit card challenge – the pilot, yeah.

Steve Rader:Yeah. And we spent $1,400 and it would have cost us $14,000 was the estimate if we had done that in house. And people were really excited about being involved in NASA’s mission. Just one thing to add onto the history because I think it was a pivotal piece to this that got us going was in 2011 just after Jeff had really gotten these pilots going, the White House Office of Science and Technology policy came through and said “Hey we’re also seeing the need for government to start using these methods, these open methods.” And you guys seem to be ahead of the game. And so would you actually stand at the center of excellence, that not just helps NASA do this, but helps all federal agencies. And actually that’s part of our – that’s what we do now. We actually help with our contracts, we run challenges for Homeland Security and this and EPA and VA. And we’ve done about 15 different agencies. And so right now there’s opioid detection challenge that is very, very important in the US government. That’s run on our contract. We just finished one with Homeland, another one with Homeland Security on improving the millimeter wave screening algorithm, which is currently not great, right? And so they’re looking to improve that. They ended up with a machine learning challenge on Kaggle that paid out 1.5 million dollars and it got an algorithm that was about 98% accurate, which just blows away what they’ve had. Their comment was that that as the best $2.5 million they spent in a long time.

Host:I wanted to ask you to explain specifically the goal of the Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation. That’s what you manage and deputy manage. It’s – you’re doing this crowdsourcing, running this from here in Houston for just NASA? Beyond NASA, to the whole government?

Lynn Buquo:So we would really like to be doing more for NASA, because we really think this technique is something that NASA could leverage. We know we have a crowd out there that would just absolutely give it their all to participate in helping NASA achieve its mission. We were originally put in place and I have to give a shout out to Jason Kruzan who was very instrumental in taking this into the world of algorithm and software development. So Jeff was here at Johnson working on human health and life sciences and R & D related to that. Jason was very interested in how the technique could be used to improve algorithms and to develop software. And so he worked kind of on that side and then the White House at the time saw what we were doing. The other agencies were just getting their authority to go to prizes and challenges, so as much as we wanted to continue having NASA use the technique, we were – because we were being successful, because the pilot had been successful – because we already had contracts in place. It was like would you guys do this? And so very early on, from very early on we started helping other agencies as well with always the goal that every time we do one of these, we learn something. So when helping the other agencies we were able to perfect how to use the challenges. And one thing that I would say to this day, we are still learning. I mean we’ve been doing this now for how many years now? Eight years now? And it’s still every challenge has something new that we learn. And always from a positive perspective. I mean there’s always the human element and the politics and the dynamics of working across different agencies with different – and different funding sources that cause – I would say we have bureaucratic hiccups we’ve had. But in terms of the –

[Laughter]

Host:See how you want to characterize that, yeah.

Lynn Buquo:The actual execution of the competitions themselves have all been terribly exciting. We’ve learned something from it. We know this techniques – technique works. We know it; we have data that proves it. We have examples that prove it. And so we are here, we are here to help NASA. We want to do more for NASA, but we’re also here to continue to have the federal government use this capability, to improve how the federal government does business.

Host:Maybe to expose my own ignorance, but it seems to me like this is new enough that you’d have a hard time finding people to work in your office, to help other people do this.

Lynn Buquo:Well I can share with you, we had, because we’re a small office. We are a small office. We have four civil servants and four contractors that are supporting us. And we just had a civil service position open up and through here at JSC of course there’s limitations, right? Here at JSC you always start with a what’s called a NETS announcement. I don’t know what the acronym stands for. But it’s to people; hey we got this job out here if you want just a lateral come over and work for us, right? And so Steve said “I just want to put in nets that this is the coolest job in the federal government.”

Host:Why not?

Lynn Buquo:And sure enough, we had real candidates that came out of the woodwork and we now have a young man who has joined our team from the Flight Ops area, former flight controller that is really excited about figuring out how we spread the use of this capability.

Host:How do you find the ways you want to reach out whether it’s inside NASA or outside the agency? How do you look for those ideas that are out there?

Steve Rader:Sure. Yeah well some of that we’re using the infrastructure that these companies that we contract with have put together, right?

Host: Okay.

Steve Rader:That’s why we’re hiring them is because they have a community of people that are set to go and they know how to reach out beyond into the public sector. Now we also use our national microphone as well as we can, right? Because we do have ways to communicate with the public that are effective. But we’re trying to get – we’re trying to cast a wide net every single time, and it’s funny that’s the easiest part of our communication in my opinion. The harder part of our communication is with our employee base.

Lynn Buquo:That’s where I was going to go. And I think that was – was the gist of your question, how do these problems arise?

Host:No, not necessarily with employees. But just in general, whether it’s looking for ideas outside or finding out about ideas that are trying to get in touch with you.

Steve Rader:Yeah

Lynn Buquo:The human network and grass roots stuff has been a big element. Senior management is well aware of the technique, they know it works and they have been supportive from a management – I’m trying to figure out how to say this diplomatically. So let me work –

Host:They let you try?

Lynn Buquo:They’re aware of it. They know it’s there. They know it’s good, right? And we’ve had project teams that have come forward that have just been wow, this has been great. We just did one for the waste management team. Kind of a joint KSC, JSC and there’s another team and they’re like this is a great technique. But what hasn’t shifted are the project plans that build into the yearly budgets, the ability to go do one of these, right? So that’s where we are now in terms of there’s senior leadership awareness, yes that this is good. There’s employee awareness. I mean Steve –

Host:To try to get institutionalized into the system.

Lynn Buquo:Yes.

Steve Rader:Exactly.

Lynn Buquo:Yes exactly. Because until management at the division and branch level have the flexibility within their budgets and are given the opportunities to test this out in terms of how they manage their projects. That’s kind of the tension – the point where I think we have the tension most right now is that there’s awareness, there’s an understanding this is great. But how do you shift the ship – the ship – the way the ship is used to operating. And for me right now is the best time. We’ve got these new programs standing up, we’ve got this – we’ve got new leadership within the agency. Now is the time for us to figure out how do we get into the project management schedules. We need to go figure out how we do a public challenge, how we use the tool set within the NASA Tournament Lab to help us because this is not a replacement. This is an additional tool available. We’re not trying to put the standard process have worked, right? They have worked.

Host:And they still will –

Lynn Buquo:And they still will, but why not take advantage of this new way of doing business that is sure to garner success for the most part? And make those leaps. It’s now – now is the time where we can use this to make those leaps.

Host:Don’t need to wait.

Lynn Buquo:You don’t need to wait.

Host:You’ve used the terms for a couple of programs that I think are part of this, NASA at Work and then NASA Tournament Lab. Could you explain what those are and what audiences they’re aimed at? Because I think I understand that they’re different.

Steve Rader:Absolutely. So NASA Tournament Lab is our public facing brand. So you won’t hear about the Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation –

Lynn Buquo:That’s a mouthful.

Steve Rader:That’s simply our office. But –

Host:It is lovely though.

Lynn Buquo:It is, and I like how you CoE-CI, get cozy with CoECI.

Steve Rader:So our NASA Tournament Lab is our public facing brand and we are part of a collection under the solve brand for the agency. So if you go to NASA.gov/solve you’ll see all of our crowd source challenges across the agency. But that includes our sister program, the centennial challenges that we’ve talked about. The international space app challenge. Citizen science – and so we have all these different programs in education as well. And so NASA terminal is simply that lab that – that brand that uses all of these commercial, what we call curated crowds, right? Those 16-17 different crowds. Our NASA at work crowd is our internal crowds. So a lot of companies are now putting employee crowds together and there’s a lot of tools out there to do that. But we’ve had this running now since 2010, 2011 with the pilot. And we’re up to I think about 24,000, 25,000 members of that which is getting close to half of the entire population of contractors and civil servants. Both contractors and civil servants can be on that platform. It – we find it most effective for what we call enterprise knowledge sharing, where you’ve got somebody working on something that applies to somebody else’s problem. And they’re able to say you’re about to go try to solve this by investing money, but I’ve actually already done some of that. So we have some really great examples of that and like Lynn says, NASA has got some of the most innovative brilliant people in the world tap into that, right? Ask hard questions, so that’s – I think that’s most of our crowd’s that we have.

Host:I still get fascinated with the whole concept of people who are out there buzzing around the internet and say, oh look there’s something where somebody is having a problem and I can help them, so I will. So I’ll volunteer.

Lynn Buquo:So we have a couple of examples. So the challenge that was done really is kind of a test to whether it would work or not. For the Mars 2020 program was okay we’re sending these vehicles all the way to Mars. And there’s deadweight on them. And Steve correct me with my technical explanation of this because I’m not deeply technical. But there’s deadweight and as the vehicle is landing that stuff is just jettisoned off of it. It’s just balanced; it’s just balance for the landing. If we’re going all the way to Mars, why are we using – why are we not using every amount available on that vehicle? So they launched a public competition to see and sure enough they got a three good solutions. One that was the grand prize winner if you will. And this gentleman had a really solid concept. I can’t remember the specifics of what his solution was, we don’t – do you remember it?

Steve Rader:Yeah.

Lynn Buquo:Say what it was.

Steve Rader:Yeah so let me back up a little bit and clarify just a little bit. So on Mars spacecraft as they’re going through – out of vacuum into the atmosphere, you can’t use jets because you’ve got atmosphere and you can’t use aero surfaces because you’re not enough atmosphere. So to actually jettison if mass and tungsten –

Lynn Buquo:Tungsten is what they use.

Steve Rader:Tungsten is what they use in order to turn this –

Host:As steering.

Steve Rader:As steering, exactly. Much like balloons used to do a long time ago.

Host: Right.

Steve Rader:And so that was – they wanted to find –

Host:But by casting off that mass – instead of a thruster. You cast off that mass which gives you the opposite reaction.

Steve Rader:Exactly, Yep. They wanted to see if – is there something we could use that mass for? If we’re taking it all the way over there and jettisoning it.

Host:Before we throw it overboard.

Lynn Buquo:For science, and they were —

Steve Rader:Or after, and in fact that’s what happened. The solution was to actually put barium tracers in – within those masses and once you jettison those tracers into the atmosphere they start to dissolve and they start to disperse in the atmosphere. And we have orbiters that actually can take mass spectrometers and examine those to find out more about the upper atmosphere of Mars.

Host:And track the markers as they disperse.

Steve Rader:Yeah, just like – anything like tracers in your blood or how you trace things. And so that was the real innovation. And this guy had no space — he was a marine science type guy from Rising Star, Texas –

Lynn Buquo:Independent consultant who lived in Rising Star, Texas. And his design was so good that they actually took him out to JPL to brief to the team. The Mars 2020 team out there. He went on to win like eight more – not our specific challenges, not NASA challenges. But he was introduced to this whole hey; I can use my brain to solve these problems. And so continued to do that. We just recently had – we just completed a challenge that we launched in partnership. Well actually the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management —

Host: Oh yeah [laughs].

Lynn Buquo:Did reimbursable agreement with us because they were really interested in figuring out how to more efficient track marine animals. And so we are very interested in how do we better use CubeSat technology in the future. So we partnered to launch this public challenge and it was the next generation of animal tracking. And this was really just to get concepts and ideas in on how could we improve the current technology. And one of the winners of this challenge it turns out that this was the third NTL challenge that he had actually been a winner in. He was one of the space poop challenge –

Host:Make a living at it.

Lynn Buquo:Yeah well what he’s excited about this one because he wants to really go ahead and look at further developing his recommendation for this technology because I think he sees a real future in it. So we have had repeat winners.

Steve Rader:And there are people that make livings out of this. There’s this mathematician in Poland who is a national hero there, who wins top coder challenges all the time, multi-million dollar type of prizes. So yeah there are definitely people who are out there. What’s interesting is most of the solutions that are useful are actually coming from this diversity of people. There’s a study that Harvard and MIT did of InnoCentives winning challenges and what they found was 70% of the time that there was a win, that solution came from somebody outside of the domain of the challenge owner. So if you’re a chemist trying to come up with a chemistry solution and innovation you have really poor changes of doing that with a team in house. You’re much likely to get that innovation that comes from outside.

Lynn Buquo:With a new perspective.

Host:I’ve felt that way and busy trying to write something and can’t quite get past my own head. I don’t know what’s going on. But if I ask somebody who’s not been involved, they can see something new about it that escaped me.

Lynn Buquo: Yeah.

Steve Rader:There’s a great – we had one where we were trying to predict solar flares and we had a two hour prediction capability. We’re trying to get that to four. And we put a challenge out and the guy who won was a retired cell phone engineer. Who happened to have an undergrad in heliophysics. And it happens that when you take the math from extracting signal from noise and apply it to a heliophysics problem you get a really good prediction and his ended up being like an eight hour prediction capability. And so it brought a whole new technique into the fold – I think they’re still building on these techniques, but it’s you know – what are these things going on in other domains that can actually be applied?

Lynn Buquo:Yeah and one of the things that was very important to us early on that was – the question of all right, we’re going out there. We’re asking the public to do this, what good is it to us? So one of our early, early focuses was on assuring that we get a usable solution. That when we get something –

Host:In any particular challenge.

Lynn Buquo:Yes for an NPL challenge we make sure because this was a lesson we learned early on. You have to have an infusion pathway for the solution that you’re going to get.

Host:An infusion pathway is a what?

Lynn Buquo:Is a, I can take it. I know what I’m going to do with it when I get it.

Host:You’re looking for something that wins that’s useful and not just the winner.

Lynn Buquo:That can be put into operational use, that changes how that project is doing its business, right? It might be small, it might be large, but when I get the something that I’ve done this competition for I can actually take that something and put it to work. Did that explain that better?

Host:Yes. You’ve given me what I was going to ask for, several examples of the way this has worked in the past. Tell me about some of the challenges that are out there now that people might be interested in.

Steve Rader:Sure well like on NASA at Work right now we’ve got one that’s looking at drug stability analysis, do we have ways that we can analyze drug stability and it’s asking folks around the agency. We’ve got one that’s a little more fun that’s trying to come up with an insignia for the new gateway program. Letting people do a graphic thing. We actually did one a while back that was looking at user concepts for how we would pioneer Mars and we did it in short story format. To kind of pull on those people that as a hobby do writing, right? And so we actually got a lot of little short stories that helped us flesh out –

Host:Without the need of having to do the math to figure out how it would actually work.

Steve Rader:Exactly. Yeah, yeah. We were just looking for ops concepts. But right now gosh there’s really more going on with other agencies. I mentioned opioid detection challenge, looking at detecting opioids in the mail stream.

Lynn Buquo:Talk about the NGA challenge.

Steve Rader:The NGA, yeah. The National Geo Spatial Intelligence Agency has come to us and they actually just launched right. And this is the first of I think four phases but basically they’re in charge of modeling and measuring the magnetosphere of the entire planet. And that model is used for GPS. It’s use in all compasses, so all of that has come together and they’re spending I think $8 or $9 million dollars to run the series of challenges and they’re looking at whole new detection ideas and are going to actually fund all the way through operations. So it’s’ a really exciting set of challenges and then you know Bureau of Reclamations is doing some really interesting stuff with us, NIST is doing things on differential privacy, which is –

Host:Who’s that?

Steve Rader:NIST. So National Institute for Standards and Technology –

Lynn Buquo:Standards and Technology.

Steve Rader:Yeah and differential privacy and how do you keep data private when you really need it? So firefighters really could use information about apartment buildings. But that information is typically stored with PII that can be used against them, so there’s this whole how do you – how can you automatically take data and de-identify it? And they’re making some progress that Google and other are looking at what we’re doing to really understand this new emerging area. We got some great data science going on there.

Lynn Buquo:The Nuclear Regulatory Agency –

Steve Rader:Oh yeah, looking at nuclear threats.

Lynn Buquo:Yes.

Steve Rader:So you know, when you’re driving a van –

Host:Weapons threats or —

Steve Rader:Yeah.

Lynn Buquo:Yeah.

Host:Power plant threats?

Steve Rader:No, like driving down the street with a detector to find and literally looking at trace amounts of radioactivity and then being able to triangulate where that is. So yeah, machine learning, all of that – those communities and those challenges are really where I think the most amazing stuff is going on.

Host:There’s one that a guy in the office kept pointing to and wanted me to ask about. What is CineSpace? What is that?

Lynn Buquo:So CineSpace is – it was started by the space station program. They have a non-reimbursable agreement, space act agreement with the Houston Cinema Art Society. And it was really a way of getting the public to use all that fabulous NASA imagery that’s available out there. Because the requirement is they have to have so many minutes that they use actual NASA footage. But again they use one of the platforms that we have available and it’s to get films for a film competition if you will to support the Houston Cinema Arts Society.

Host:Okay.

Lynn Buquo:They call it the CineSpace film competition.

Steve Rader:They’re amazing, like if you go on their site and look at the past winners the stories they tell are – they’ll just rip your heart out, it was great and inspiring. They’re really inspiring.

Lynn Buquo:Yeah.

Host:I think I know kind of where the answer to this last question is going, but I want to give you the opportunity to say it. Is your work here now a fully developed program that’s ready to go out on its own or are you still blowing this up?

Steve Rader:We’re working across the whole agency and across the whole federal government. We would love for it to have a higher adoption rate.

Lynn Buquo:Yes, because – yeah and I think we are mature in our operational model. We know how to use this stuff now. We know what to look for. Like I said earlier we’re still learning and we still think there are more projects at NASA. More specific things at NASA that could use this capability. We’re really not about building an empire here with this, but really about trying to get organizations to use it and infuse it into the standard way that we do non-standard stuff.

Steve Rader:A lot of people still see it as a novelty. They don’t see it as a core tool, and a lot of that – you know it’s a little threatening into your psyche. If you feel like you were the innovator, it feels weird to think that somebody else is going to bring that idea. And we try to get people past that. We try to get people to really own the problem, and realize that solutions are actually built on technologies and ideas that come from all over the place, you know? When you use that Excel spreadsheet to come up with your great stuff, you don’t feel bad about that, right? But somebody else develop that, right? And so leveraging the best of what’s going on out there as building blocks in the end makes our workers the heroes, right?

Lynn Buquo:Yes.

Steve Rader:They’re the ones that if you can come up with an ecosystem that weighs half as much and uses tenth of the power, you’re going to be a hero. No matter how many contests and other people help with that. Like the fact that you actually did a competition to go find that and bring it all to bear that’s the important part. And we’re really – that’s the thing that we’re working with our employees.

Lynn Buquo:That’s the hardest thing —

Steve Rader: The participation out in the public has just been amazing. That resource and its part of a bigger trend going on right now. The gig economy, the freelance work and crowds all kind of intersect and there’s a real movement of mobilizing people in ways that engage their passion and make the most use and can navigate the large amounts of technology and expertise that’s coming. Just think about how fast things are changing.

Host:Yes.

Steve Rader: That rate of change is so fast now that traditional models of trying to keep people educated just are falling short. And a lot of these newer models, a lot of what people are going in the crowd and free-lance and gig, they are actually doing lifelong learning. They’re scaling all the time but they’re doing it outside of the work place and then applying it on these platforms, so it’s kind of an interesting time we live in.

Host:It is interesting and it also sounds a whole lot more fun than traditional procurement.

Lynn Buquo:We make traditional procurement fun. How’s that? That’s our tagline.

Host:Procurement just awarded us an innovation award.

Lynn Buquo:Most of the companies we work with are small business by the way. So that helps too.

Steve Rader:We don’t think about it but innovation in our government processes is actually where we have to be focusing. It’s not just about technology. It’s about where in our regulations do we need to be changing to adapt, like the world is changing, we need to find innovative ways to change along with it.

Host:In order for it to keep up.

Lynn Buquo:Yeah. Really.

Host:Great, Lynn Buquo and Steve Rader, thank you very much. This is terrific.

Lynn Buquo:Thank you Pat. This was fun. [Laughter]

Steve Rader:Thanks.

[ Music ]

Host:That was a lot of good information and a lot of stuff that I did not know anything about before today. And the best way for you to check out the Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation online is at NASA.gov/CoECI, that’s C-O-E-C-I. You can get more information and search for imagery and subscribed to the NASA crowdsourcing ListServ, get ideas. In fact, they even suggested to me that you could go there and leave ideas for the podcast. You can go online to keep up with all things NASA at NASA.gov, but also be a good idea for you to follow us on Facebook and Twitter and Instagram. You will thank me. And when you go to those sites, use the #askNASA to submit a question or suggest a topic for us. Remember to indicate that it is for Houston we have a podcast. You can go find the full catalog of all of our other episodes by going to NASA.gov/podcasts. When you do, check out many other NASA podcasts, all for them cool that you can also find there. Many of them all available right there at the same spot where you can find us at NASA.gov/podcast. This podcast was recorded April 2, 2019. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Gary Jordan, Norah Moran and Sarah Schlieder for their help with the production and to our guests Lynn Buquo and Steve Rader. We’ll be back next week.