“Houston, We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

Episode 5 features Randy “Komrade” Bresnik, NASA Astronaut, who talks about his time aboard the shuttle and what it was like to have his daughter be born during that mission. Bresnik also describes the different types of training that astronauts have to endure to be successful in space, including having to live in an underwater habitat. This episode was recorded on May 4th, 2017.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (host): Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 5: Astronaut Training. I’m Gary Jordan and I’ll be your host today. So this is the podcast where we bring in the experts– NASA scientists, engineers, astronauts– all to tell you the coolest things about NASA. So today we’re talking about astronaut training with Randy Bresnik, known by his colleagues as Komrade. He’s a U.S. astronaut here at the johnson space center in Houston, Texas. Well, actually, he’s in space right now. He just launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome and arrived at the international space station last week, July 28th, to start his long duration space flight. But before he launched I had a chance to chat with him, and we had a great discussion about what astronauts have to study, know, and endure to be successful in space. So with no further delay, let’s go light speed and jump right into our talk with Mr. Randy Bresnik. Enjoy.

[ music ]

>> t minus five seconds and counting. Mark. [ radio chatter, music ]

>> Houston, we have a podcast.

[ music ]

Host:all right, well, thanks for coming, randy. I know you had some back to back stuff going on today, so I appreciate you taking actually the time to sit down and talk with me for just a little bit. And so close to your launch, too. I know, like, this– it’s going to be pretty busy up until the time that you actually are in space. And maybe by the time this podcast actually gets launched, you will actually be there, so this will be kind of appropriate with how busy and how quickly things are moving. So today, I kind of wanted to talk about astronaut training. You know, what you have to go through in order to prepare yourself to go to space, and there’s just so much– it has to be so diverse. Not only do you have to be a jack of all trades, but you have to be sort of like a master of all of them. I did want to start off with, though, first of all– I’m reading your name here. It’s randy “Komrade” Bresnik. What’s the story behind Komrade?

Randy Bresnik:it’s a call sign from the marine corps. I come from the fighter community, where I was flying f-18s. And typically we’ve always historically given call signs to people, you know, going back to World War II– “Pappy” Boynton. You know, these are nicknames that people had. “Indian Joe” Bauer, you know, was a squadron commander back when the squadron I was in was in world war ii. And so we have these call signs, and you get one either for your name or for something you done stupid. [ laughter ] and so an example that makes it really easy for people to understand is there was a guy who was in training command. He’s out there doing [ indistinct ] quals for the first time, and in the catapult getting ready to get launched off the bow of the ship. Those things accelerate you from 0 to 150 knots in under 2 seconds. And so you are going flying because this thing has so much mechanical power.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:well, he kept his feet on the brakes. [ laughter ] brakes were not going to hold an aircraft carrier from launching him, and so, you know, the catapult launches, the brakes– the brakes– he was holding– the tires blow. And so he ended up with the call sign “bam bam.” [ laughter ] and so, you know, I didn’t have anything that stuck until I got to the f-18 training squadron, and on my first flight with a marine instructor. And he asked if I had a call sign, and I said, “hey, they’ve given me this, that, that…” and he said, “no, those all stink. I’ll think of something.” And so we go flying in the f-18. I had an amazing time. You know, it was the plane I always wanted to fly. It was just a phenomenal airplane. And he come back in the debrief when we’re done and he goes, “all right, I have a call sign for you.” I’m like, “okay,” knowing these things sometimes can stick. He goes, “Bresnik, Bresnik. That sounds like Brezhnev. We’re going to call you Komrade. Komrade Brezhnev. [ laughter] and that was it. And I– you know, here I am quite a few decades later, and haven’t done anything stupid to get a new one. [ laughter]

Host:Brezhnev after the soviet leader?

Randy Bresnik:Leonid Brezhnev, yeah.

Host:okay, and I guess everyone called each other Komrade as like a—

Randy Bresnik:that’s– during soviet times that was how everybody addressed themselves.

Host:how– okay, I get the reference now. So just as a little bit of background, but– you’re navy and marines, is that correct?

Randy Bresnik:I am a– the overall arching is naval aviator, which includes the navy and the marine corps aviators. We wear the same wings on our fl– we earn the same wings in flight school and wear the same wings on our flight suits.

Host:okay, so when you talk about launching off of carriers and the marines—

Randy Bresnik:right, that’s part of our overall naval aviator training. So I was trained to launch off an aircraft carrier– launched a t-2, a-4, and an f-18. But then as a marine we deploy expeditionarity– is that even a word? [ laughter ]

Host:we’ll make it a word.

Randy Bresnik:we’re expedition based, but we’ll launch and establish forward bases and fly out of there, so just flying off the aircraft carrier.

Host:okay, okay. Now, you’re going to be launching soon– or, depending on when this podcast is released, you’re in space right now– but this is not your first rodeo, right? You’ve been in space before. You launched in 2009 on sts-129 aboard Atlantis. How was that?

Randy Bresnik:sts-129 was really neat. I had, fortunately, a really great crew. We had two marine test pilots, we had two navy test pilots, and we had two smart guys. [ laughter ] our smart guys– you know, Leland Melvin, here he is, he had been drafted into the NFL, playing football, but had a career-ending injury, but he finished his education, went back and got his master’s, became a NASA engineer, and then became an astronaut.

Host:awesome.

Randy Bresnik:yeah, and then because we had the two marines, you need to, you know, raise the average IQ on the flight, and so we had Bobby Satcher, who is MIT PhD in chemical engineering, and that wasn’t enough so he went to Harvard and became a medical doctor as well– you know, oncologist. And so he was there to try and make us all look good.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:and great guys. Butch Wilmore, myself, and bobby were all first time flyers.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:but the other three experienced crew were phenomenal mentors and taught us how to do what we needed to do on our training so when we were able to go to space we were able to execute very well, and, you know, hit all the tasks we needed to during the mission and call it a success.

Host:now, compared to like international space station missions now, I mean, we’re talking about six months ish on the space station.

Randy Bresnik:yeah.

Host:this was relatively short, right? Just over ten days aboard. So I mean, you really had to soak it all in for those ten days.

Randy Bresnik:and it is– we say the shuttle flights were a sprint and a station flight is a marathon, you know.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:you– for a shuttle flight, you trained for every minute of that flight because it’s all– once you launch, you’ve got every minute of every day chock full of events.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:and so you’re able to practice and rehearse that.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:whereas, space station, we don’t have that luxury. I mean, you don’t know what you’re doing next week because something may break, or something may change, or priorities may be adjusted. And so we do skills based training so that if I can do this particular task, well, I can do a hundred tasks like that.

Host:and this is for the space station.

Randy Bresnik:for space station.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:and so we do the skills based training so I’ve got skills in all these different areas, and we’ll see how that skill will be put to use maybe 10 or 20, 30 different areas during those 6 months, but I don’t sit there and rehearse what I’m doing daily.

Host:right. So when you were on the shuttle, you did two EVAs, right? So you rehearsed those.

Randy Bresnik:we did.

Host:and you had a lot of experience with– you knew exactly what you were doing. This was in the neutral buoyancy laboratory that you did that?

Randy Bresnik:the neutral buoyancy lab– world’s largest swimming pool.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:six million gallons of water.

Host:a lot of water.

Randy Bresnik:you know, the whole space station’s underneath it. We used to have the shuttle in there when we were flying shuttle.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:and– I don’t know. I’m talking with my hands, you know, because this is a podcast. [ laughter ] but you know, it’s just a pilot thing.

Host:you look good when you’re doing it. I don’t– I can justify that. [ laughter ]

Randy Bresnik:and you know, we rehearsed each EVA six or seven times. I mean, every single time, exactly what we were doing very well. And here I am, you know, Monday I’m going for my last NBL run here before the flight.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:and you know, we’ve done a handful of runs of a bunch of different types of skills, not knowing if I’ll do any of those particular things I rehearsed, or I’ll be doing stuff I completely did not rehearse. But I’ve got a wide enough skill base to be able to, you know, do anything that comes– you know, that we end up having to have happen, either planned or unplanned.

Host:yeah, I mean, I hear a lot of times that, you know, you go into the neutral buoyancy laboratory and it kind of becomes almost muscle memory. You kind of like know where you’re going, you know the, I guess, lay of the land a little bit.

Randy Bresnik:that’s the whole point.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:you know, with any of the training we do, space is such a unique environment physically, because your body’s feeling the weightlessness.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:visually, because you’re seeing the whole earth go underneath you, and especially when you’re outside in that space suit– you know, your own personal spacecraft– and especially when you’re underneath and you’re holding onto something, and you look down and your whole life had told you– “wow, there’s nothing between me and the earth but my boots, and that’s 200 miles. If I let go, I’m going to fall.” Because your whole life has taught you that here on earth.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:and it’s a physical thing you have to overcome. And so to be able to have the muscle memory to go, “I just go to this spot. I put my tether here. I pull out this piece of equipment,” you can rely on that and give you the comfortability of the training.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:then you’re able to not have it be such an overwhelming or physically stressful event.

Host:okay. Well, so one cool thing about your two EVAs is something happened in between there. You want to talk a little bit about that?

Randy Bresnik:sure. I left earth with my wife and son watching, and my daughter, who was nine months in the womb at the time. [ laughter ] and you know, the funny thing was the morning of that launch we strap in, and the weather was iffy, and really, it was getting to the point where a few minutes before launch, you know, up until 15 minutes before launch, our commander, who had the best view, was kind of going, “yeah, it’s not looking so good, guys.” And so we started kind of getting prepared that hey, we might actually scrub. And we’re hearing the calls over the radio, and the guy who’s the S.T.A. pilot said, “hey, there’s a hole that’s coming over here,” and we came out of a nine-minute hold because there was a hole that was just aligning weather-wise that would allow us to launch, and we came out of that nine-minute hold going, “we’re going.” We were like, “wow, that’s great!” But, you know, at that point, I knew that, hey, I wasn’t going to be around for the birth of our daughter.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:and so we launch, we get going on the mission, we get docked to the space station, we knock out our first spacewalk. I’m the I.V., or the guy being basically the director of the two guys out there on the EVA.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:and the plan was, you know, just because she had to be induced, they were going to have her deliver the next day, before my first EVA. And so they induced my wife, and Abigail didn’t come out.

Host:oh! [ laughter ]

Randy Bresnik:she did not come. And so we wake up the next morning, and I’m expecting to wake up the morning of my first EVA and find out that my wife gave birth. Well, she’s still in labor. That’s not good. And so– but the EVAs happen, and we practice it these six times, and the mission’s got to go, so I had to compartmentalize and go, “okay.” And we had the thing– you know, once we start prepping for the EVA, you know, whatever happens, I don’t find out about it till we actually come back in the door. So, get suited up to our work, go out the door for my first EVA. You know, thinking about it afterwards I was kind of expecting when I came back in that– to hear that she would’ve been born.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:and just think, “wow, what are the odds that I’m outside on a spacewalk the same time my wife’s giving birth to our daughter?” And so we come back in, you know, put on the rack, and they pull off our helmet, I’m like—

Host:“is she born? Is she born?”

Randy Bresnik:nothing! Still in labor.

Host:no! [ laughter ]

Randy Bresnik:so I’m feeling really bad for my wife.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:you know, something us men just really don’t understand, and to have it go that long, I know it’s just very painful. And unfortunately, it was. But in the end, she got to be there and give birth to our daughter. And so the next– that night, go to sleep, and expecting to hear in the morning that our daughter was born. I ended up having to get up to use the facilities in the middle of the night, and I saw the KU band pass, so I quick called down, and get a hold of her sister on the cell phone, and she’s like, “she’s still in labor.”

Host:still! Oh, my.

Randy Bresnik:so I– yeah, they were pretty busy down there, so I just kind of put the phone down on the table next to the– in the delivery room, and so I was able to hear the sounds of the delivery room until the KU pass went down, and turns out she was born about 20 minutes after the KU pass ended.

Host:no! You just missed it.

Randy Bresnik:so when I got up the next morning, the morning wake up song was “butterfly kisses” that my wife had picked out as the song to play the morning our daughter’s born.

Host:so you knew.

Randy Bresnik:that’s how I knew, but I hadn’t heard from my wife yet. I said, “they’re playing the song. Does that mean it happened?” So a few minutes later, they patched my wife through, and I was able to talk to her.

Host:that is amazing. Talk about– I mean, you used the word compartmentalize. That, I can’t even imagine. You’re like– you’re so concerned about your wife, and you’re like, “but I have this EVA to do, and I need to focus.”

Randy Bresnik:the whole, you know, sp– our whole shuttle crew and our whole sts-129 team and our whole space program got us to that point to do that EVA to do this construction stuff.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:and yeah, there’s not– failure’s not an option, you know. You’ve got to focus.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:and then, certainly, when you’re outside in your own personal space suit– spacecraft– you know, in the most inhospitable location known to man because it’s +250 degrees in the sun and -250 degrees in the shade, there’s no margin for error. And so you have to compartmentalize, and so as a pilot and a test pilot that was the most– you know, the culmination of my career. “I’m in space. Now I’m going on a spacewalk. This is unbeliEVAble!” And the view was just indescribably beautiful.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:and then the very next day, to have something surpass that was just very fortunate, very blessed to be able to have experienced that.

Host:wow.

Randy Bresnik:I wish I could’ve been there for my wife and been there at the delivery, but, you know, that was not the plan for us, and so we were just given grace we were able to do our jobs in respective areas of the planet– or off-planet– and good news after that. And the next day, waiting the whole day, you know, waiting until I could finally see pictures.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:and get a little video sent to me. And then a few minutes after that, I was actually able to get on a two-way video conference with my wife and see her, and hear her little voice. And that was pretty special, but literally, my commander was at the node 2 waiting until I finished, kind of tapping his watch, because as soon as I hung up from that video conference, I had to float down into the airlock and close the hatch, and Bobby Satcher and I had to depress for– down to 10.2 psis for the overnight camp-out to get the nitrogen out of our bodies for the EVA the next day, where now I’m the ev 1, I’m the lead for the spacewalk.

Host:oh, wow.

Randy Bresnik:so back to the– compartmentalize to the last spacewalk of the flight.

Host:wow. All right, “my daughter’s born. That’s cool. Okay, now I’ve got to go–” yeah, I– that’s just what you have to do. And then that was a, I guess, overnight purging. They don’t do that anymore, right? They just do—

Randy Bresnik:we don’t– we do it– called in suit light exercise.

Host:I see.

Randy Bresnik:where we’re able to use less overall oxygen from the station to be more efficient with the oxygen we have up there.

Host:ah, makes sense. Okay. Well, so now you’re gearing up for a six-month journey. So tell us a little bit about the sort of training that has to go– you know, I guess, a little bit– how is it different in general from shuttle training? But just what all do you have to do to prepare yourself? Like, what kinds of training does an astronaut have to do to be up there for six months?

Randy Bresnik:certainly there’s a lot of, you know, station training because you’re up there for so much and you’ve got to be able to do everything. You’ve got to be able to execute the payloads and experiments. At the same time, you’ve got to be able to do the earth’s observation. You’ve got to be able to do the events, so talk to people down here on the earth and share the experience, on top of being the janitor. You’ve got to clean up the vents and wipe down the handrails, and make sure the station is in clean situation.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:we’ve got to be able to fix things that break. Toilet breaks, you’re not calling the plumber. You are the plumber!

Host:you are the plumber.

Randy Bresnik:yeah, you are the scientist, you are the plumber, you are the fix and repair man.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:and so that’s where a lot of the training is, is when we talk about the skills based stuff is how do I go ahead and fix this particular type of thing? How do I work this type of fitting, which is on a hundred different pieces of equipment, but I know how to work that fitting, you know?

Host:I see.

Randy Bresnik:important stuff, like our regenerative ECLS systems, you know, the environmental control and life support– the oxygen generator, the carbon dioxide scrubber, those types of things.

Host:got to learn how to fix that, yeah.

Randy Bresnik:really important to station, and so we’ve got to learn in depth how to fix those if they break.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:that’s the stuff that we really– you know, we’re proving– I say it’s a proving ground for exploration, because when we launch to mars, we can’t have spare setup. We can’t, if there’s a problem, just deorbit and come back to earth in a couple hours. We’ve got to have it all there. It’s all got to work, and it’s got to keep working for years at a time to be able to get there, do our mission, then come back.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:and so we’re proving those technologies now.

Host:that’s amazing.

Randy Bresnik:and with the current time where we don’t have the shuttle and we don’t have our Starliner or our dragon crewed vehicles yet, our only way to space is through our Russian partners.

Host:that’s right– Soyuz.

Randy Bresnik:and so 60% of the time of my last year and a half has been in Russia.

Host:oh!

Randy Bresnik:training to launch, you know, rendezvous, dock, and then land on the Soyuz.

Host:so what’s your role on the Soyuz?

Randy Bresnik:on the Soyuz I’m in the left seat, what they call the flight engineer.

Host:okay.

Randy Bresnik:and so my Russian crewmate, Sergey Ryazansky, is in the center seat. He’s the commander of the Soyuz. And so between the two of us, we work and run all the systems within the Soyuz. And then our flight engineer number 2– now, because we’ve changed crews a little bit here recently—

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:Paolo despoil from Italy. And so the three of us will be launching July 28th.

Host:so 60% of your time, I guess, you said for the past year and a half has been over there– wow. That’s– it must be a complicated system then, right?

Randy Bresnik:it’s complicated. There’s also the Russian segment training that we get, because that’s a good half a station. We typically don’t work down there daily, but especially just being– I guess I’ll be the commander of the ISS for expedition 53. I kind of need to know what’s going on in the whole station.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:so I get training so I can be helpful to those guys, know what’s going on, and then if necessary, make decisions based on the health of the entire space station.

Host:that’s awesome. So what kind– you know, you’re there for so long. What are you going over? Are you going over mostly how to work the thing? Or, you know, if this goes wrong, this is what’s– like, emergency situations?

Randy Bresnik:mostly that.

Host:oh, I see.

Randy Bresnik:and that’s the same thing, because it’s a dynamic flying vehicle. That’s the dangerous part of the mission.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:same thing with shuttle. We did so many sims just for ascent, entry, and landing.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:and fortunately, the majority of that training that we got, we never had to use. But if you had to use it, your life depended on it, you know. And it was very time critical, so that’s why costs and rehearsal over those things.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:not to mention the fact that you’re in Russia and doing this stuff in Russia, and that there’s a little bit of extra margin that you have to add for that, because that’s not one of the easier languages.

Host:I hear that’s one of the more difficult parts of training, is Russian language. That’s– you’re right, it’s very difficult. I’m starting training here in the next couple weeks, and I’m nervous. I’m very nervous. [ laughter ] so I mean, being an astronaut, though, is not just flying the vehicles and fixing stuff, you know. You have to be in tip top shape, right? There’s a physical element to it. Every astronaut is just in super good– do you guys have like– do you have physical requirements? Like you have to work out this much time? Or, you know, even medical– do you have to learn how to, in case of an emergency, patch someone up or anything like that?

Randy Bresnik:all right, so sounds like two questions there.

Host:I guess it is two questions, yes.

Randy Bresnik:yeah, certainly the work out point, the better shape your body is in, the better it will be able to respond and adapt to zero gravity and then maintain itself when it doesn’t have gravity to help keep your bones strong and your muscles strong and all that. So that’s certainly one of the bigger concerns about leaving, you know, you van allen radiation belt, which protects us here in low earth orbit and on the planet, and going too far off destinations. How do we protect the physical body of the crew so that when they get to somewhere they can do the exploration we want to do?

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:so there’s a lot of us either– the protection from radiation, there’s protection from zero gravity, and we do have a lot of countermeasures down. That’s why space station and being up there for six months gives us really good insight, is to do– you know, since you don’t get the sun. You know, can we up your vitamin d? Can we get the certain diet? Can we get the proper exercise with aerobic and anaerobic exercise to keep the body from, you know, deteriorating in zero g, which it would normally do? You know, they say being up there is like a person having osteoporosis. And so you can’t just do nothing, otherwise you come back in bad shape having lost a lot of bone.

Host:so you train how to use the, I guess, workout equipment.

Randy Bresnik:right, the workout equipment, which is, you know, amazing. The advanced resistive exercise device is a [ indistinct ] that does all kinds of different stuff, and people are coming back in better shape than they leave sometimes. Part is the fact that we have to dedicate a couple hours every day to working out.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:you know, your body– you know, here on earth, standing up and sitting down out of a chair, getting out of bed, getting out of your car, walking to work– those little things that you do if you’re not quote “exercising” like we would think, you’re still– your body’s moving. In space, you’re floating around. You’re not doing anything difficult all day long. So that’s the only exercise you really get.

Host:ah. Yeah, because otherwise there would be that kind of natural deterioration.

Randy Bresnik:yeah.

Host:wow. We had an episode beforehand where we talked with John Charles, where if your body doesn’t need your bones and muscles because it’s not using it as much, then your body says, “all right, we don’t need to put any energy towards that.”

Randy Bresnik:exactly.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:and so then the medical question, yeah, I mean, there’s no doctors there. So we train to kind of have telemedicine and things like that that are really– technology’s really allowing us to do well now these days.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:we’re the eyes and ears for the doctor. We’re like space EMTs. We can do the initial triage. And we train for somebody who’s not breathing, or someone who’s had– they don’t have a heartbeat.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:we can take care of all that stuff on orbit, stabilize him, and then get the docs involved and figure out how to do follow-on treatment, or, if necessary for medical emergency, evacuation of the space station.

Host:and you guys are running through these procedures kind of repetitively, I would assume, right? Yeah.

Randy Bresnik:yep, got to build the muscle memory, you know. And fortunately we’ve got great procedures and great training that allows it to be– okay, we can get the person to here by stuff that we’ve learned and memorized, and then we open up the [ indistinct ] and go, “okay, here’s where we’re at.” And then we can sync up with the ground and go, “here’s what’s next. Hey, doc, you got any other idea? Here’s a video camera picture of the patient. Here’s what we’re seeing. Okay, we all agree. We should give him this particular, you know, medicine or something like that that they need.” So it’s really a group effort.

Host:I’m imagining– I was a lifeguard way back in high school, and I’m imagining just kind of like that but a million times more complicated. Because it’s the same thing, right? You’re sitting and watching a pool, but every once in a while something goes wrong and you’ve got to know what to do. So you have kind of a unique set of experiences. Not only are you an astronaut, but you’re an aquanaut and a cavenaut. I want to start with the cavenaut. What is a cavenaut? What did you do in a cave? I guess you lived in a cave, right?

Randy Bresnik:we did. The European space agency, back in 2011, started this expeditionary and extreme environment training called caves.

Host:okay.

Randy Bresnik:and they originally planned it as kind of a cooperative behavior thing, kind of more of a– how do you get along with people in– you know, put the astronauts all together and put them in little stressful situations and see how they evolve, and how they– you know, the personality skills and that kind of stuff.

Host:mm-hmm.

Randy Bresnik:and it was in the caves, the vast, vast underground cave system in Sardinia, Italy, which is an island off the west coast of the main body of Italy.

Host:okay.

Randy Bresnik:and so you start out, just like on any training, with basic caving stuff, and rappelling, and climbing. And then you went into [ indistinct ] in a day where you’re in these really narrow caves and it’s really winding about, getting lost, and navigation, and being able to go through squeezes, and navigating through tiny areas of the cave to be able to overcome any claustrophobia or anything like that. Another day we did a whole space photog– or cave photography and how to map out and allow us to make maps from the data we collect in the caves, from laser range fired, how big is the room, what shape is it, how is the inclination. Put that all together to the final exercise, which is a week underground. And you head in a kilometer and a half from the opening of the cave.

Host:ooh.

Randy Bresnik:and that’s where the base camp was. [ laughter ] and we’re in this tens of kilometers long cave, and there was a point where the maps ended, and our job was to go out every day and map out new parts of the cave. So we decided what hole, dark spot, to go into and check out– see if that was a dead end or if that was somewhere to go, and going back further and further into the cave. And you know, it’s amazing going through a tiny area– kind of like squeezing through a toilet seat, almost, you know– and opening up to a cathedral sized room underground. You’re going, “holy– I’m underground. Look at this huge area!”

Host:whoa.

Randy Bresnik:there were no trails, no lights, no guardrails.

Host:right, because you’re mapping it, you’re discovering it.

Randy Bresnik:you’re mapping it. You feel– very few humans have ever seen this.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:and it’s unlike anything you’ve ever seen on the earth or seen pictures of. I mean, it’s just—

Host:wow.

Randy Bresnik:and so you got this real feeling for exploring. You’re like, “okay, I’m excited and ready. Hey, we can either go this way or that way. Let’s go that way today and let’s see what’s over there!”

Host:that’s so cool.

Randy Bresnik:and so it was really, really an enjoyable thing to do with these other people, other astronauts who are just as excited about this exploring, too. And really applicable to what we do in space, because what they found from doing these caves exercise is that there’s a lot more space applications than they thought. Because in space, you don’t know what time it is, because every 45 minutes, you get a sunrise, and then a sunset, and that goes– happens 16 times a day.

Host:right.

Randy Bresnik:well, in a cave it’s dark all the time, so you never know what time it is. You could just be marching along, doing stuff and realize, “oh, my. Why do I feel tired? Oh, I’ve been up for 20 hours!” You know, “I forgot to eat!” Because it’s just– I didn’t have, “oh yeah, it’s lunchtime,” you know.

Host:yeah, you kind of have to adjust, like make up, almost, a biological clock as you don’t have a sun.

Randy Bresnik:and they’re like– so there’s no guardrails, there’s no paths. There definitely is an apparent fear of death. You could be doing stuff with your– attached onto a guideline, and it could be 200 feet– if you take a slip and you’re not attached, you’re 200 feet.

Host:whoa.

Randy Bresnik:I mean, it’s very much like being in space where if you’re on a spacewalk and something goes wrong and you’re not tethered properly, you know, it’s a bad day.

Host:wow. Did you– I mean, once you got set up, I guess, on base camp, did you light up everything so you could see a little bit? Or was it pretty much—

Randy Bresnik:you had your helmet light. That was it.

Host:that was it? The entire time?

Randy Bresnik:and you got used to it. And that was pretty neat. And so that made photography really interesting because what you would do is you’d put the thing on manual, open the shutter, and then you’d take a flash. And you’d hit it a couple different times and just point it at different areas of the cave, trying to not point it at the camera, kind of shield it with your body, so you could light up different cells. So it was kind of like painting by the numbers. You’re just painting with lights, with the flash, or even flashlights. You could actually do, you know, squiggles and write words with the flashlight and what it was showing on places.

Host:wow.

Randy Bresnik:so you then close the shutter and see what showed up on the screen, see what you got, because you couldn’t tell– there was flash and lights moving all around during the picture. And then you look to see what it all amalgamated to at the end. It was really neat.

Host:that’s amazing. Wow. I guess– what was it like seeing the sun for the first time after being there for so long?

Randy Bresnik:it was really bright. And I was in the cave with Thomas Pesquet and Tim Peake. And when we came out, Thomas was like, “the sky is a different blue. They changed the blue!” It was just so vibrant. And the other thing that was so amazing was that, you know, the sights and sounds and smells in the cave are all very– you know, very much the same. And we came out after that week, and literally, you could smell every bush, and the dirt, and the grass. I mean, it was just shocking, just so sensory overload with your smell.

Host:yeah, because I guess your body adapted to not—

Randy Bresnik:to not having it.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:and so very much like, you know, you hear people coming back from space station, where you don’t have the fresh smells, or the breeze from the wind that modulates. You have the constant breeze of the air ducts and the ventilation system. And certainly the smells are pretty standard up there. And you come back and you just– you know, feeling the grass under your toes, and this and that. I mean, we’re supposed to be landing in December. I’m like– smell– I’m sure snow will have a smell when I come back, like, “that’s fresh snow! That’s awesome.” [ laughter ]

Host:okay, so we have like one more minute, but I did want to ask, I wanted to follow up about the aquanaut experience, what it was like to live underwater.

Randy Bresnik:that was amazing, too, because I’ve been scuba diving for years, and just loved how unique that environment is, the wildlife underneath there. And the Aquarius habitat right now is the only thing on the planet where people can go live underwater.

Host:wow.

Randy Bresnik:there’s actually been less aquanauts– people that’ve spent more than 24 hours underwater– than there have been astronauts.

Host:oh!

Randy Bresnik:and so that’s a pretty interesting fact.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:and the interesting thing like that is, again like the caves, there is an apparent fear of death. I mean, you’ve got– you’re 40 feet underwater, but once you’re saturated, that’s not safety. Something goes wrong with your equipment, you can’t just do an emergency ascent. Going to the surface will kill you.

Host:yeah.

Randy Bresnik:you have to get back inside, and we have to, you know, use the habitat as a hyperbaric chamber.

Host:wow.

Randy Bresnik:and so you are– you’ve got to figure out what’s going on. And so buddy checks, checking your gear, just like we do on spacewalk, very important. Knowing where your buddy is and what he’s doing, in case you have a problem that you can go over somewhere and buddy breathe. Things like that that, you know, have to be in your mind the whole time you’re doing a simulated spacewalk underground. And then be able to live underwater and see the cycles of the fish, and what fish were active at daylight, what fish were active at nighttime, you know. And just seeing that whole thing unfold around you every day just made it a really amazing experience. And you’re in this habitat that’s the size of like a school bus– there’s six of you living and working for a week! And you’ve got to figure out how to get over any individual issues you might have, and be able to be an effective member of the team. And between those different extreme environments, the hope is that when someone finally gets the chance to go to space, that it’s just one of many extreme environment things that they can add to their repertoire. It’s not such a huge, overall assault on their senses and their physical being because they’ve been in extreme places before. This is just one more, rather than the first one they see.

Host:yeah, it sounds like you’re taking little things from each experience. You know, from the cavenaut, you’re taking adjusting your biological clock. From aquanaut, you’re taking, you know, the comradery and buddy checks, making sure everyone’s okay. Obviously there’s got to be more, but just that whole round experience make you like truly a naut. I don’t know, an all-naut? I’m making up words here. Anyway, well, Komrade, thank you for coming on the show. I know you’re a very busy man. So just best of luck to your mission. Maybe by the time this is up here you’ll already be up there, so again, best of luck to you. For the listeners, if you want to stay tuned till after the little music here, we’ll tell you how you can follow Komrade on his journey. He’s on Facebook, twitter, and Instagram, if I’m correct, right?

Randy Bresnik:correct.

Host:all right, so we’ll tell you about that after the show. So thanks again, Komrade.

Randy Bresnik:my pleasure, and good luck with the podcast.

Host:thanks.

[ music ]

[ indistinct radio chatter ]

>> welcome to space.

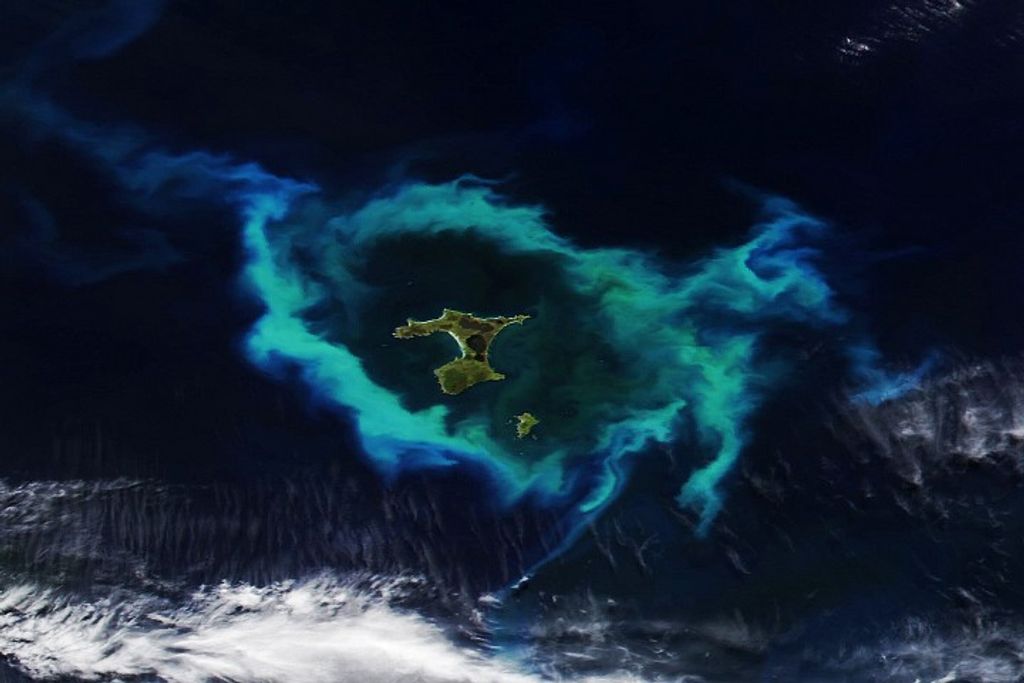

Host:hey, thanks for sticking around. So today we talked with astronaut randy “Komrade” Bresnik. And he is very active on social media– Facebook, twitter, and Instagram. On Facebook, he’s NASA astronaut randy “Komrade” Bresnik. On twitter, @astroKomrade and on Instagram, also @astroKomrade. You can follow him on any one of those accounts. You can actually just search and find– just search randy Bresnik and he’ll probably pop up. He’s verified on all the other accounts. And he shares pictures of his experience onboard, and some images of the earth, so please follow along. If you want to see the whole journey of the international space station– that’s where he is right now– that’s also on all of those platforms– Facebook, twitter, and Instagram. On Facebook, it’s the international space station page. On twitter, @space_station and on Instagram, it’s @iss. Just use the hashtag #askNASA on any one of those platforms and you can submit an idea to the podcast, or maybe ask a question, and we’ll make sure to address it in one of the later podcasts. This podcast was recorded on May 4th, so may the 4th be with you. It’s probably way too late for that, but that’s okay. We’re recording it on May 4th. I’m really in the mood. Thanks to John Stoll, Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, and John streetwear for helping out with this episode, and thanks again to Mr. Randy Bresnik for coming on the show. We’ll be back next week.