On Aug. 30, 1983, space shuttle Challenger thundered into the sky at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida in the first night launch of the space shuttle program.

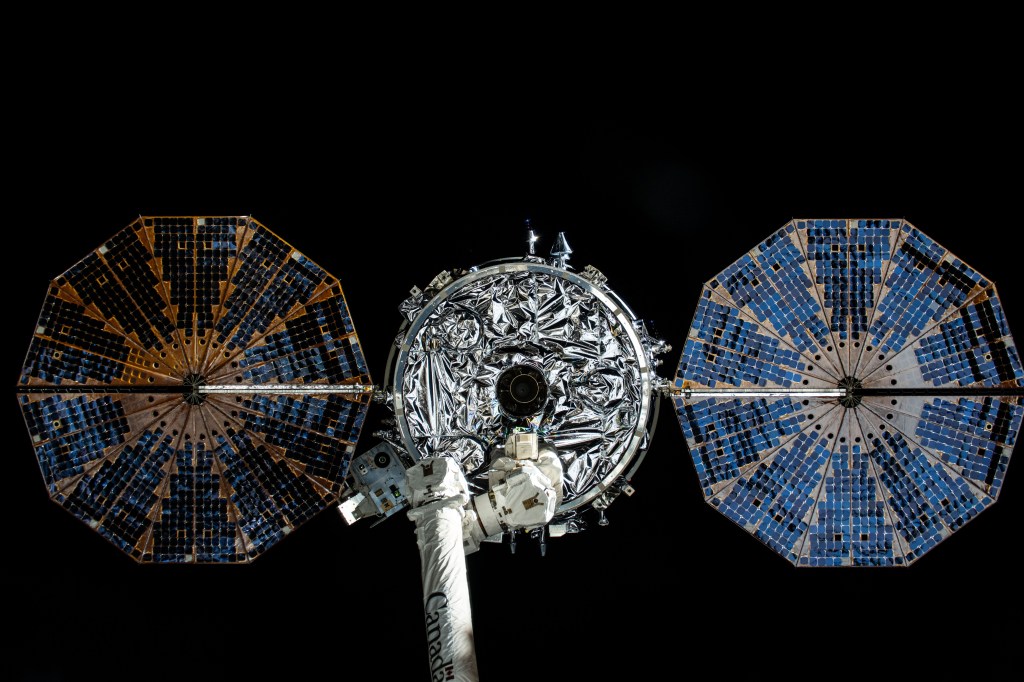

On Aug. 30, 1983, space shuttle Challenger thundered into the sky at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida in the first night launch of the space shuttle program. The STS-8 crew consisted of Commander Richard H. Truly, Pilot Daniel C. Brandenstein, and Mission Specialists Dale A. Gardner, Guion “Guy” S. Bluford, and Dr. William E. Thornton – Bluford becoming the first African American in space. At 54, Thornton became the oldest person in space up to that time. Bluford deployed the Insat-1B satellite for India, the mission’s primary payload. Truly and Gardner maneuvered the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS), or robotic arm, with the 8,500-pound Payload Flight Test Article (PFTA) to test the arm’s capabilities. Thornton, a medical doctor, conducted space motion sickness studies throughout the mission. On Sept. 5, the crew made the first night landing of the shuttle program at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) in California.

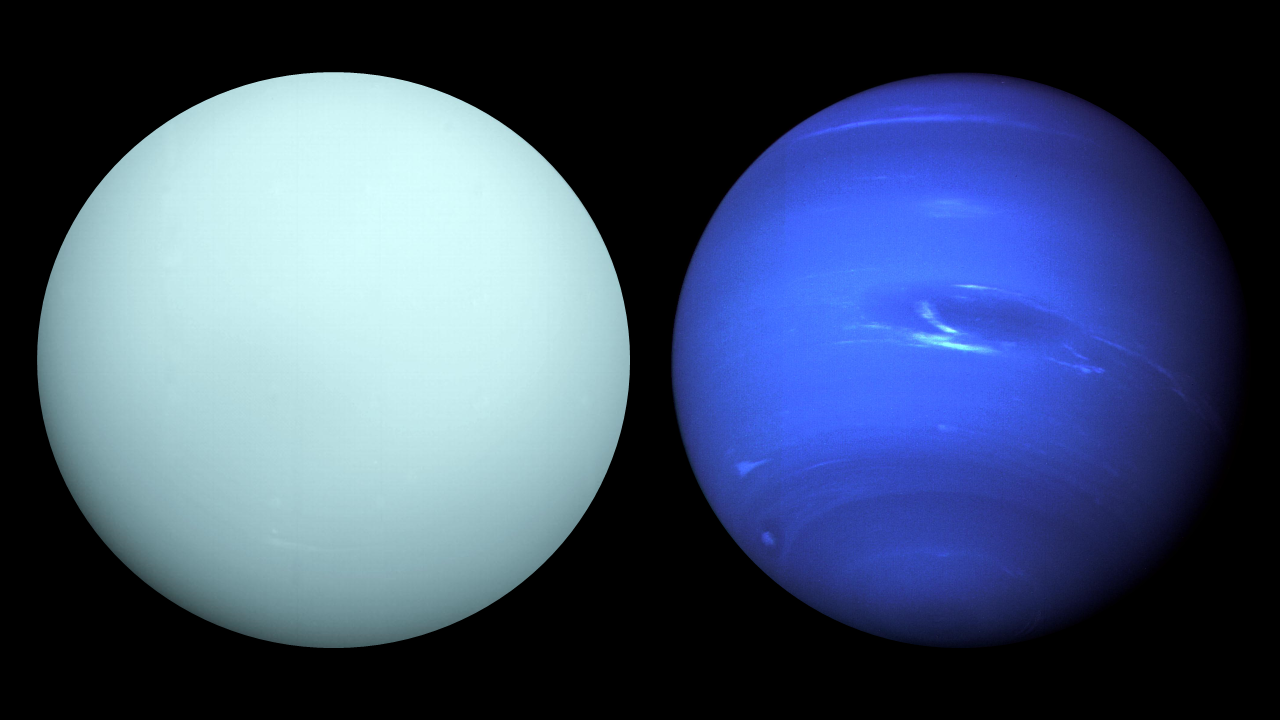

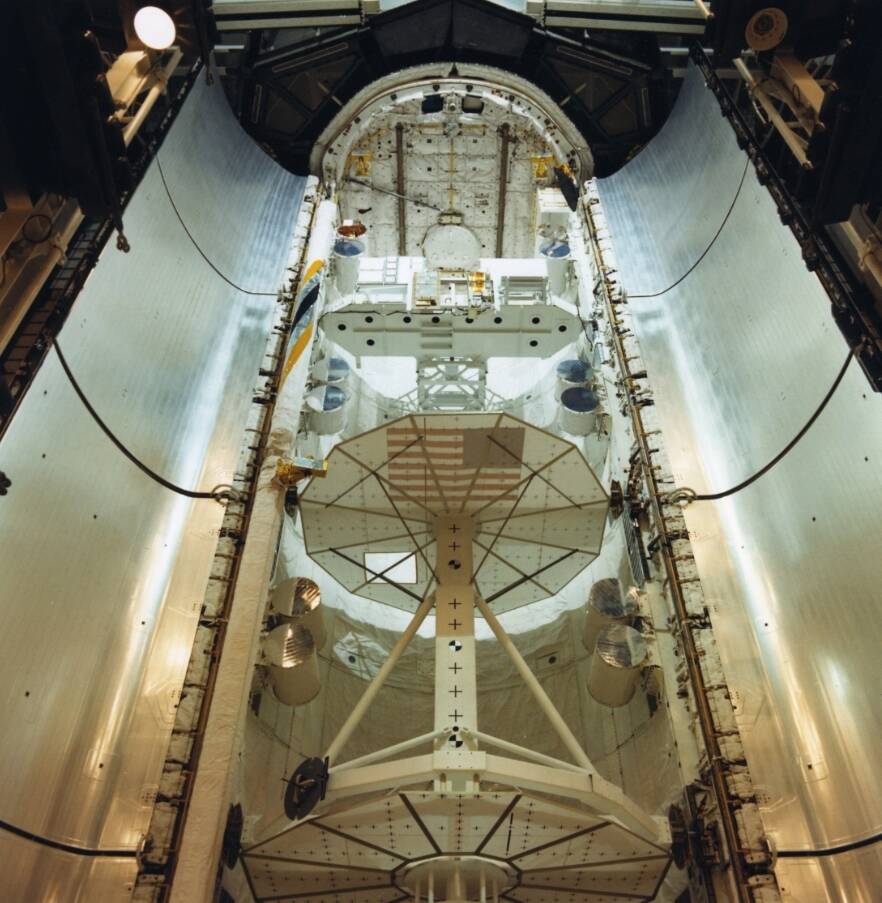

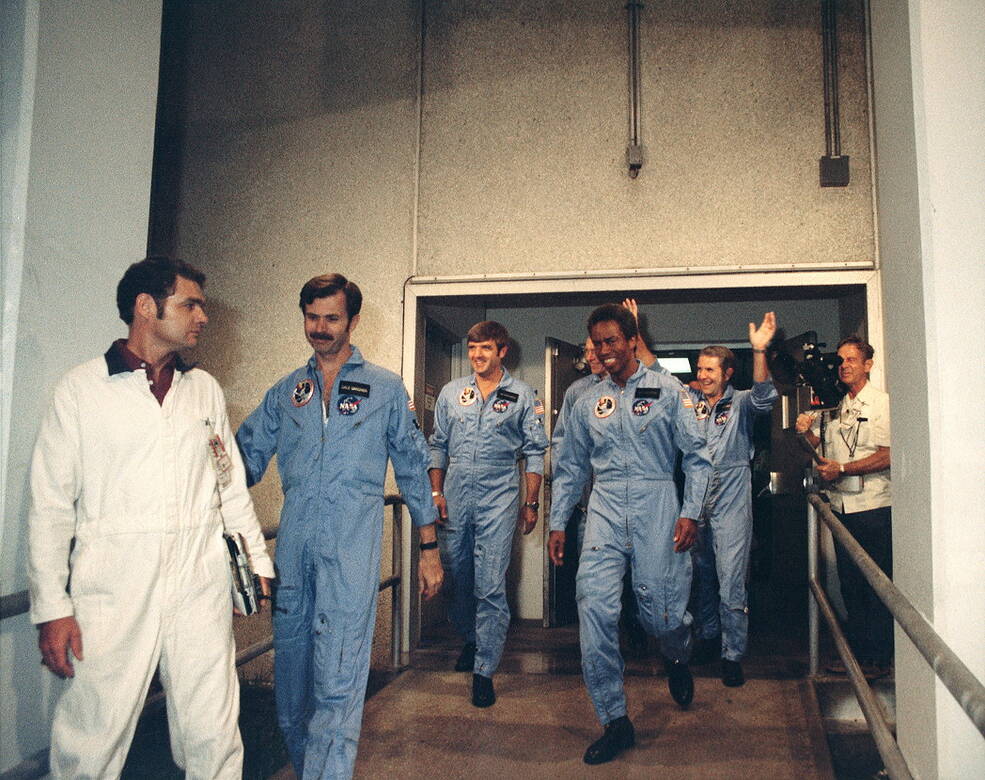

Left: The STS-8 crew patch. Middle: The STS-8 crew Daniel C. Brandenstein, left, Dale A. Gardner, Richard H. Truly, Dr. William E. Thornton, and Guion “Guy” S. Bluford. Right: Challenger’s payload bay, with the PFTA visible – the Insat 1B satellite is just out of frame at bottom.

When NASA originally planned the mission, STS-8 comprised a crew of four on a three-day mission in July 1983 aboard space shuttle Challenger to deploy the second Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) and the Insat-1B weather and communications satellite operated by the Indian Space Research Organization. The deployment and placement in orbit of Insat-1B, because of orbital mechanics, dictated that the shuttle launch at night, and also land at night, both firsts for the program. On April 29, 1982, the same day the agency introduced the STS-7 crew, NASA named Truly, a veteran of STS-2, and rookies from the astronaut class of 1978 Brandenstein, Gardner, and Bluford to STS-8. Bluford held the honor of the first African American named to a U.S. space crew. Following instances of space motion sickness among about one-third of astronauts on early space shuttle missions, on Dec. 21, 1982, NASA assigned physician-astronauts Dr. Norman E. Thagard and Dr. Thornton as mission specialists to STS-7 and STS-8, respectively, to conduct inflight studies to better understand the phenomenon. For Thornton, selected as a scientist-astronaut in 1967, the assignment meant the end of a long wait. A major change to the STS-8 payload complement occurred after the failure of the Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) to place the first TDRS into its proper orbit on STS-6 in April 1983. In May, NASA decided to remove the second TDRS from STS-8 because engineers had not yet determined a cause of the IUS failure. In its place, NASA accelerated the flight of the PFTA, an 8,500-pound dumbbell shaped payload, from STS-11, providing an earlier opportunity to test the dynamics of the RMS with a heavy asymmetrical object. Managers delayed STS-8 until August, to give engineers enough time to place TDRS-1 into its proper orbit and complete its checkout. Testing of the TDRS system during STS-8 became a critical item prior to the STS-9/Spacelab 1 mission that required the high data capacity for its complex scientific mission. In Challenger’s middeck, the Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System (CFES) flew for the fourth time, while the Animal Enclosure Module (AEM) containing six rats made its first flight. All the changes resulted in managers adding two days to the mission’s duration, making it a five-day flight.

Left: Workers at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida tow Challenger from the Orbiter Processing Facility to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB). Middle: Challenger begins its rollout from the VAB to Launch Pad 39A. Right: Challenger arrives at Launch Pad 39A.

On June 24, 1983, Challenger returned to Earth at Edwards AFB in California from its previous mission, STS-7, and five days later arrived back at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Technicians refurbished the orbiter, mated it with its twin Solid Rocket Boosters and External Tank and rolled the stack out to Launch Pad 39A on Aug. 2, a then-record fast turnaround time. While on the pad, the stack rode out Hurricane Barry that made landfall just south of KSC. After participating in a successful countdown demonstration test on Aug. 4, the STS-8 astronauts returned to KSC on Aug. 27, the same day the countdown began, to prepare for the launch.

Left: The STS-8 crew prepares to board the van to take them to Launch Pad 39A. Middle: Liftoff of STS-8 on the first night launch of the space shuttle program. Right: Controllers in Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston watch a replay of the STS-8 launch, Flight Director Jay H. Greene, left, and capsule communicators (capcoms) with Guy S. Gardner and Bryan D. O’Connor.

On Aug. 30, Challenger and its crew thundered into the night sky at KSC, only the second night launch in the American human space flight program – the first was Apollo 17 in 1972. As soon as the shuttle cleared the launch tower, control of the flight shifted from KSC to Mission Control at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, where Flight Director Jay H. Greene led his Emerald Team of controllers that monitored every aspect of the mission. Bryan D. O’Connor, assisted by Guy S. Gardner, served as the capsule communicator, or capcom, the astronaut who talks directly with the crew. Following the powered ascent and two burns of Challenger’s Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) engines, the astronauts had safely reached orbit. They removed their helmets, unstrapped from their seats, and completed the first major task, opening the payload bay doors that also deployed the radiators to cool the shuttle. They also connected the communications system to TDRS, with excellent quality and nearly doubling the time when the shuttle could communicate with Mission Control. Gardner activated the RMS and completed an initial checkout, and in the middeck Bluford activated the CFES to begin the first experiment session. Thornton began his series of medical investigations, with crew members coming in and out of his “clinic” for various studies. In Mission Control, Greene’s team handed off to Harold “Hal” M. Draughon and his Crystal Team with John E. Blaha taking over as capcom, assisted by Dr. William F. Fisher. The astronauts gathered in the middeck for a television broadcast, with all of them sporting three white dots on their foreheads – electrodes for Thornton’s eye movement experiment. At the end of the crew’s day, Thornton reported on the success he had with several of his experiments. After that, the astronauts began their first sleep period in space. A change of shift took place in Mission Control to Flight Director Greene’s Emerald Team, with O’Connor returning as capcom. Near the end of the astronauts’ sleep period, another change of shift took place, with Flight Director Brock R. “Randy” Stone’s Amber Team taking their consoles to see the astronauts through their busy second flight day.

Left: The STS-8 crew deploys the Insat-1B satellite for India. Middle: The STS-8 crew during the congratulatory telephone call from President Ronald W. Reagan. Right: Guion “Guy” S. Bluford works with the Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System experiment.

To begin the astronauts’ first full day in space, Mission Control played Georgia Tech’s fight song “White and Gold” for alma mater Truly. “That’s the spirit,” Truly responded. “We’ll roust everybody up and we’re ready to move.” Capcom Jeffrey A. Hoffman wished them a good morning. Mary L. Cleave served as backup capcom on this shift. As the day before, Thornton busied himself with the medical experiments, with his crew mates taking turns as subjects, while Bluford finished up the CFES experiment runs for the mission. With Truly, Brandenstein, and Gardner, Bluford prepared for the Insat-1B deployment, the major activity for the day. After receiving a go to deploy from Mission Control, Truly commanded Challenger into the proper release attitude, and Bluford initiated the release sequence. The actual deploy took place with Challenger out of contact with the ground, but when they reacquired communications, all had gone well and Insat was on its way! After the deploy, the crew fired Challenger’s OMS engines for six seconds to separate from Insat. The Crystal Team came back on console to take the crew through the rest of its day, with Fisher on as capcom. The astronauts took a congratulatory call from President Ronald W. Reagan from his ranch near Santa Barbara in California, accompanied by live television from Challenger. Soon after, the astronauts settled down for their second night’s sleep in space.

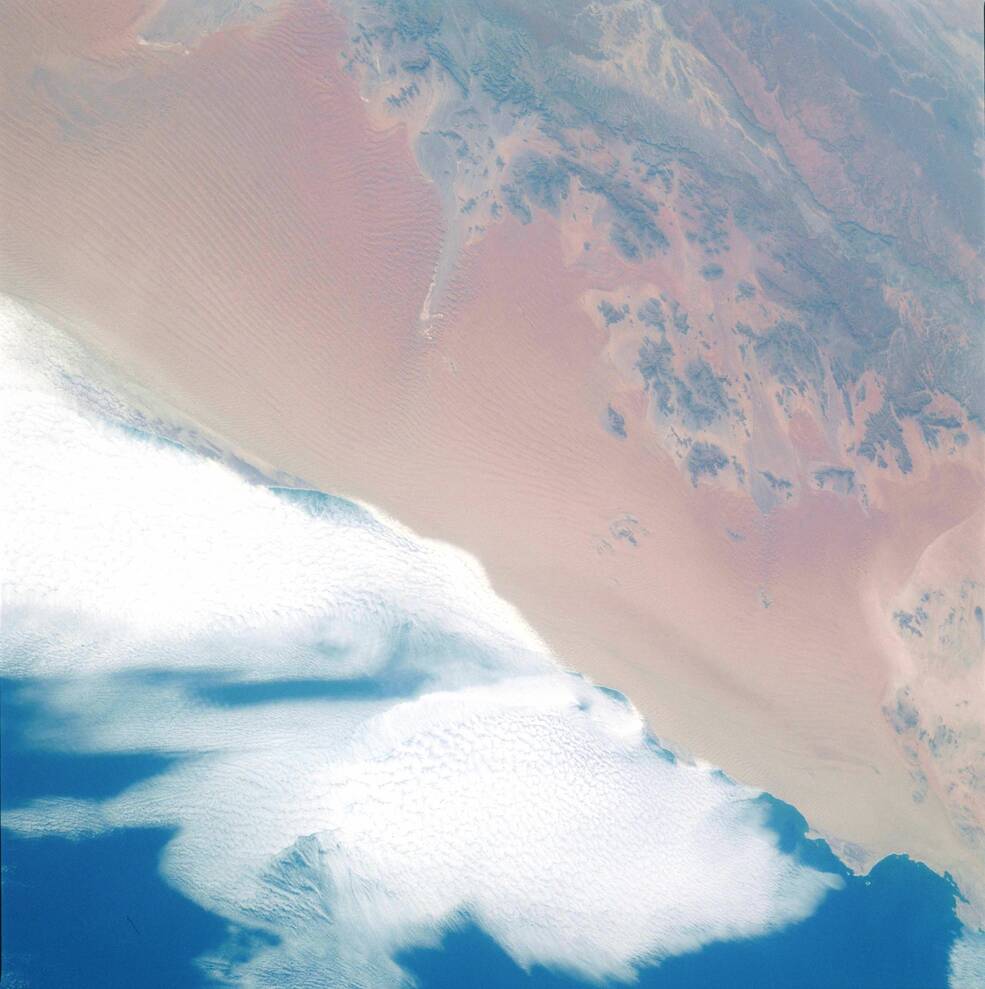

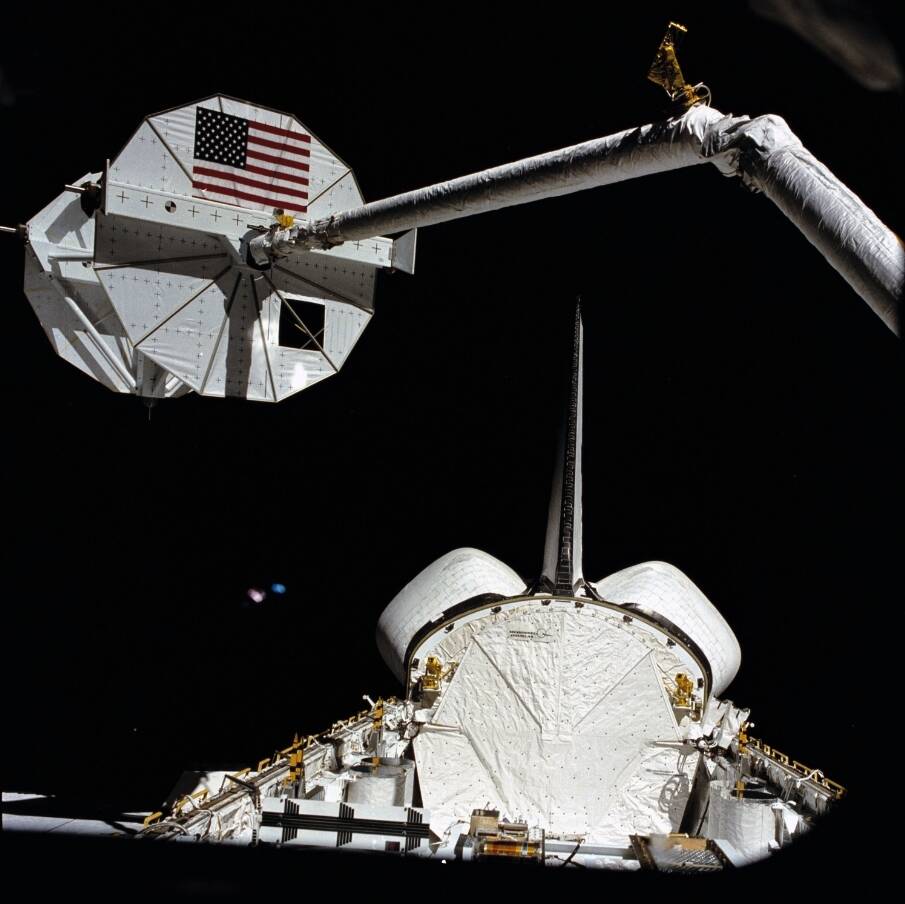

Left: The Payload Flight Test Article at the end of the Remote Manipulator System during the first day of testing. Middle: The Kalahari Desert in Namibia. Right: Dr. William E. Thornton, right, takes a break from his medical studies in the middeck to observe the PFTA activities and take in the scenery of the Earth.

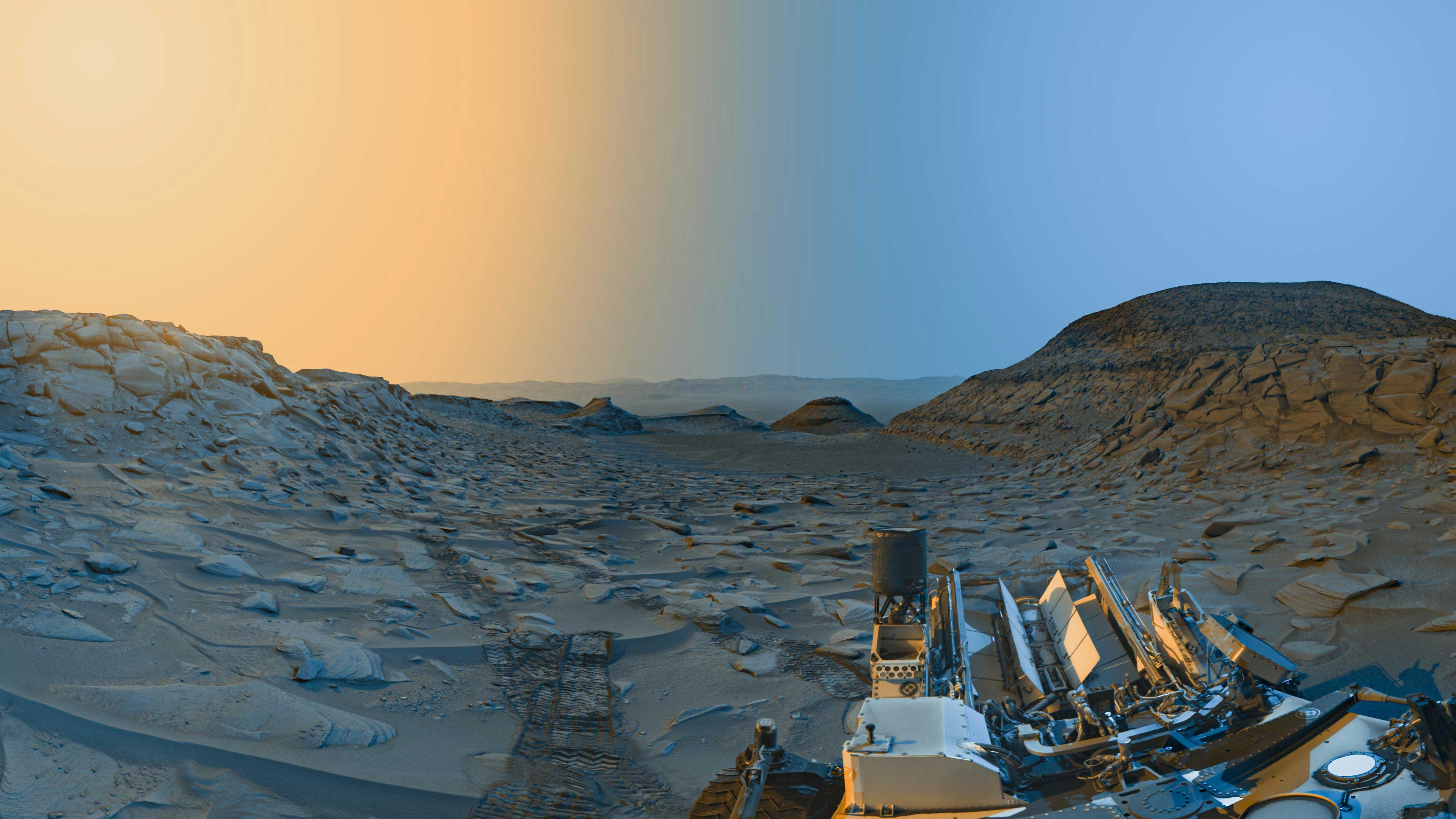

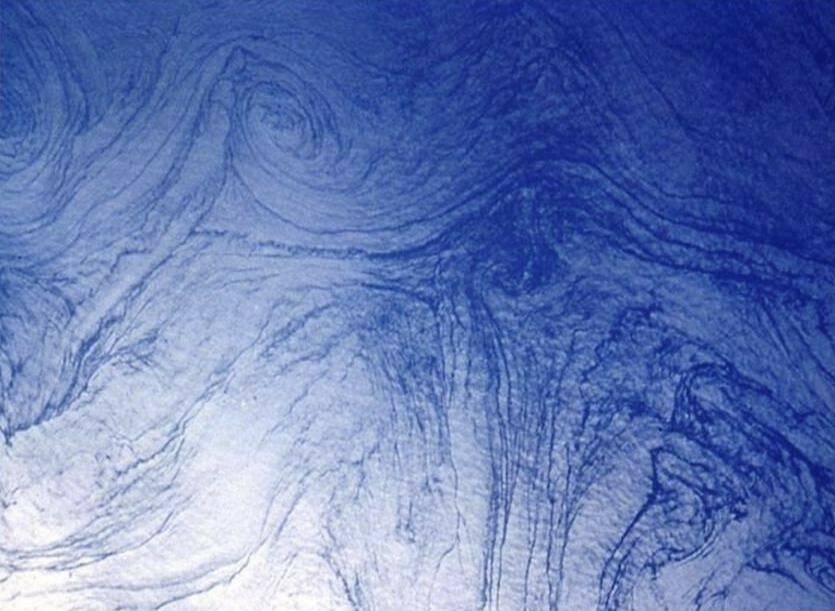

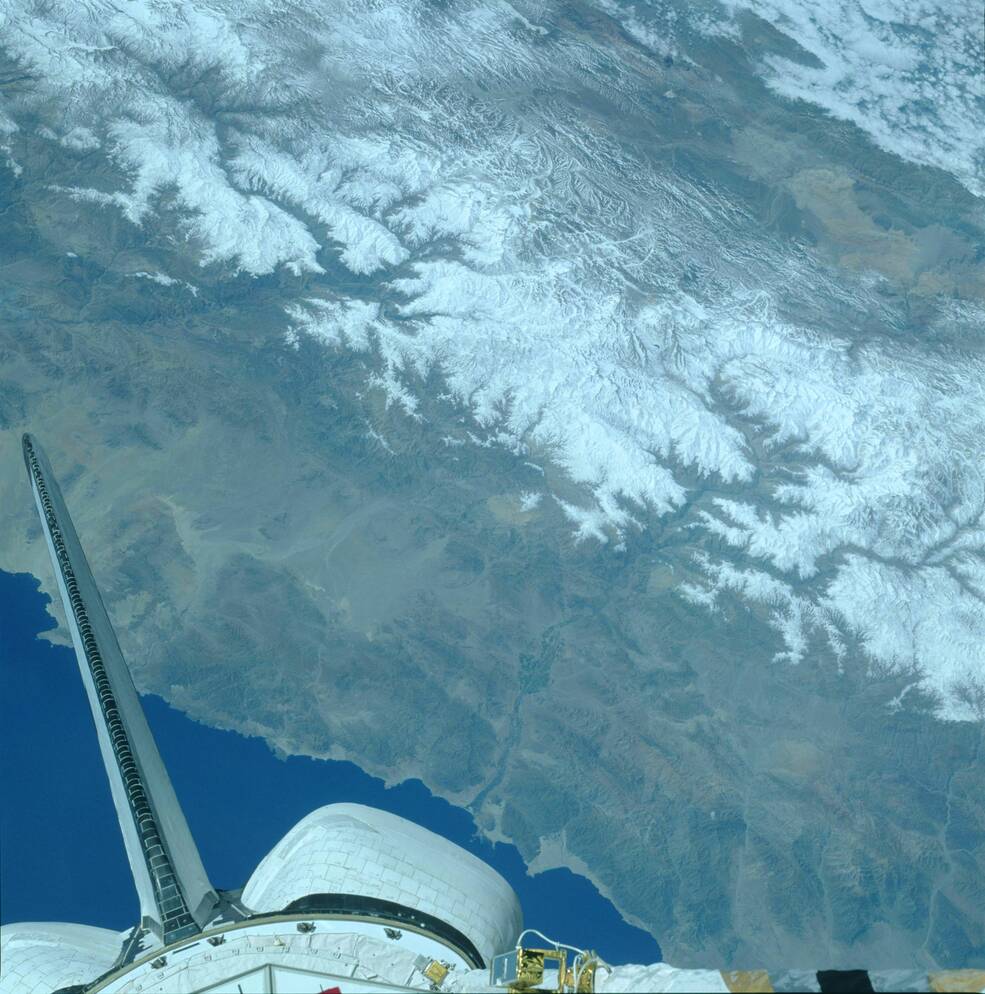

The wake up music to start their third flight day, the University of Illinois Fight Song, pleased alum Gardner, who called it “a great song.” As they began activating the RMS for the PFTA tests, Truly recognized that the city of Houston celebrated its 147th birthday on the day they launched. He used the RMS to grapple the PFTA at its grapple fixture number 2 and then unberth the PFTA from its cradle in the payload bay. For the next five hours, Truly and Gardner put the RMS and PFTA through several tests, wiggling the RMS to see the effects on the shuttle, and firing the shuttle’s thrusters to determine the stability of the RMS. During a scheduled meal break, some of the crew members decided instead to sightsee as the shuttle passed over southern Africa, marveling at the colors of the Namibian desert and the ocean currents in the Mozambique Channel. Near the end of the day, Thornton provided a summary of his activities of the past two days, with virtually all tasks accomplished with only minor hardware problems. The astronauts settled down to dinner and soon after began their next sleep period.

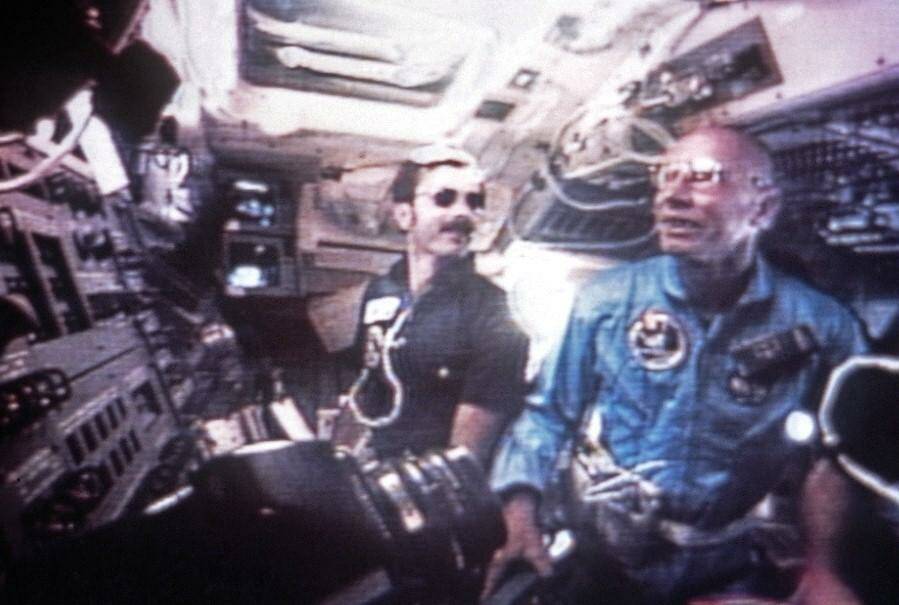

Left: The Payload Flight Test Article (PFTA) at the end of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) during the second day of testing. Middle: STS-8 astronauts Dale A. Gardner, left, and Daniel C. Brandenstein during the second day of PFTA and RMS testing. Right: Gardner conducting one of the neuro-vestibular experiments.

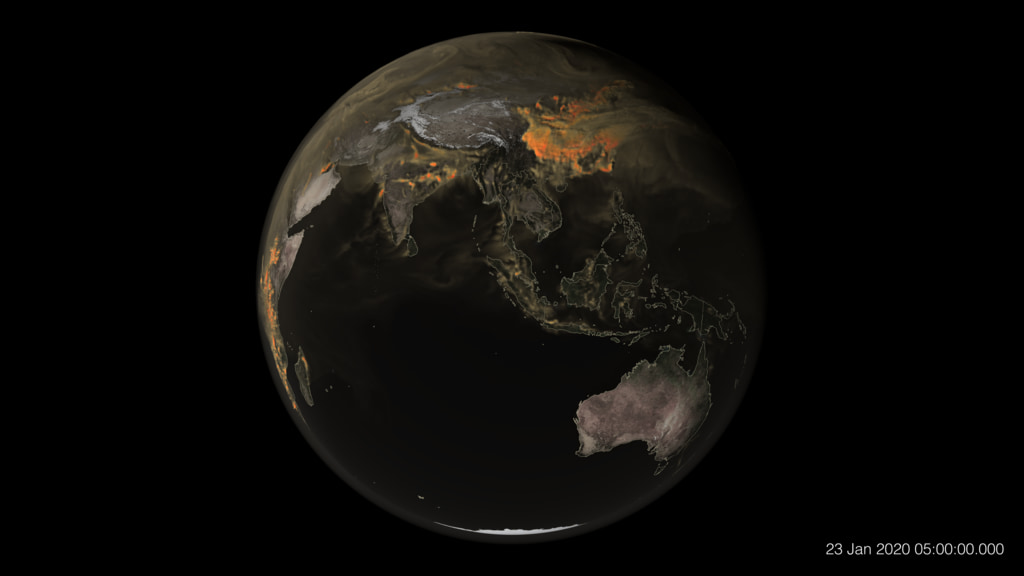

To begin the crew’s fourth day, Mission Control played the Penn State Fight Song, Bluford’s alma mater. He said he “really enjoyed that Nittany fight song.” The morning’s flight plan called for two OMS burns to lower Challenger’s orbit from about 184 miles to 139 miles to enable studies on the effects of atomic oxygen, more plentiful at lower altitudes, on the shuttle. During one of the burns, Gardner and Thornton filmed themselves in the middeck as the acceleration from the engines caused them to move in the opposite direction. With Gardner and Truly once again at the controls, they put the RMS and PFTA through similar exercises as the previous day, but with the RMS grappling the PFTA at grapple fixture number 5. Like the day before, they didn’t encounter any problems and found the RMS very reliable. Near the end of the crew day, Thornton once again provided a summary of his activities.

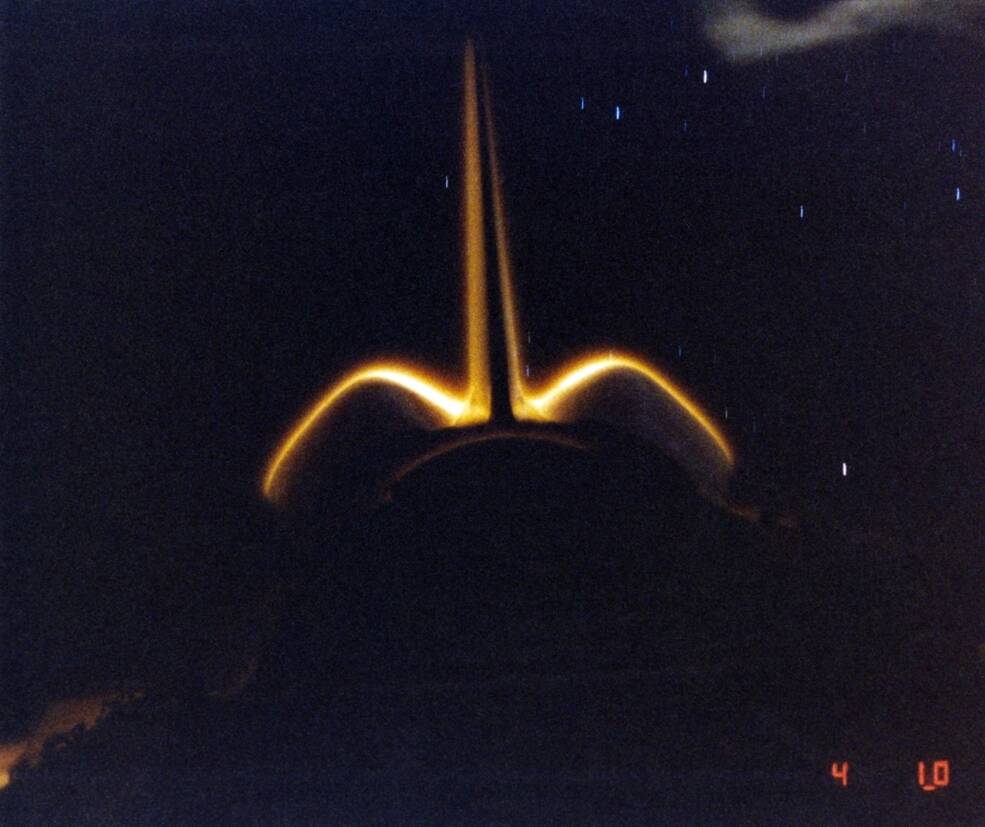

Left: The tail glow caused by atomic oxygen. Middle: The STS-8 crew during the inflight press conference. Right: The underside of Challenger during the video survey with the Remote Manipulator System.

Mission Control began the astronauts’ fifth day in space by playing the University of North Carolina Fight Song for alum Thornton. Brandenstein passed along Thornton’s “good morning” to Mission Control, adding that “he’s already hard at work in his office,” meaning he had already begun his data gathering in the middeck. The astronauts photographed a phenomenon call tail glow, when the aft end of the shuttle seems to glow from interaction with atomic oxygen and most prominent following thruster firings. Truly and Brandenstein completed a star tracker acquisition test to aid in shuttle navigation. All five crew members participated in an inflight press conference with six reporters at JSC, the 24-minute event made possible by TDRS that enabled live TV of the crew. When a reporter asked Truly for his assessment of STS-8’s contribution to the overall space shuttle program, he responded, “You have to really remember that this press conference is coming from space in the most complicated machine in the world, and while we all have been down here for how many minutes, it runs itself. We really have made great strides, I think. And I think it’s a great future for America in space.” When asked if his studies had revealed anything new about space motion sickness, Thornton replied, “I have learned more in the first hour and a half on orbit here than I had by all of the literature research that I’d done and all the active work in the past year.” Following the press conference, Truly picked up the PFTA, operating the RMS in manual mode, meaning without computer assistance, and then handed control of the RMS to Gardner to finish the task by stowing the PFTA. Gardner then commanded the RMS to conduct a videotaped survey of the underside of the orbiter, an activity never performed before. Thornton conducted a video demonstration of his various experiments, with his crewmates actively participating. At the end of the day, he provided his usual summary of another busy day of data collection. The crew then settled down for a good night’s sleep.

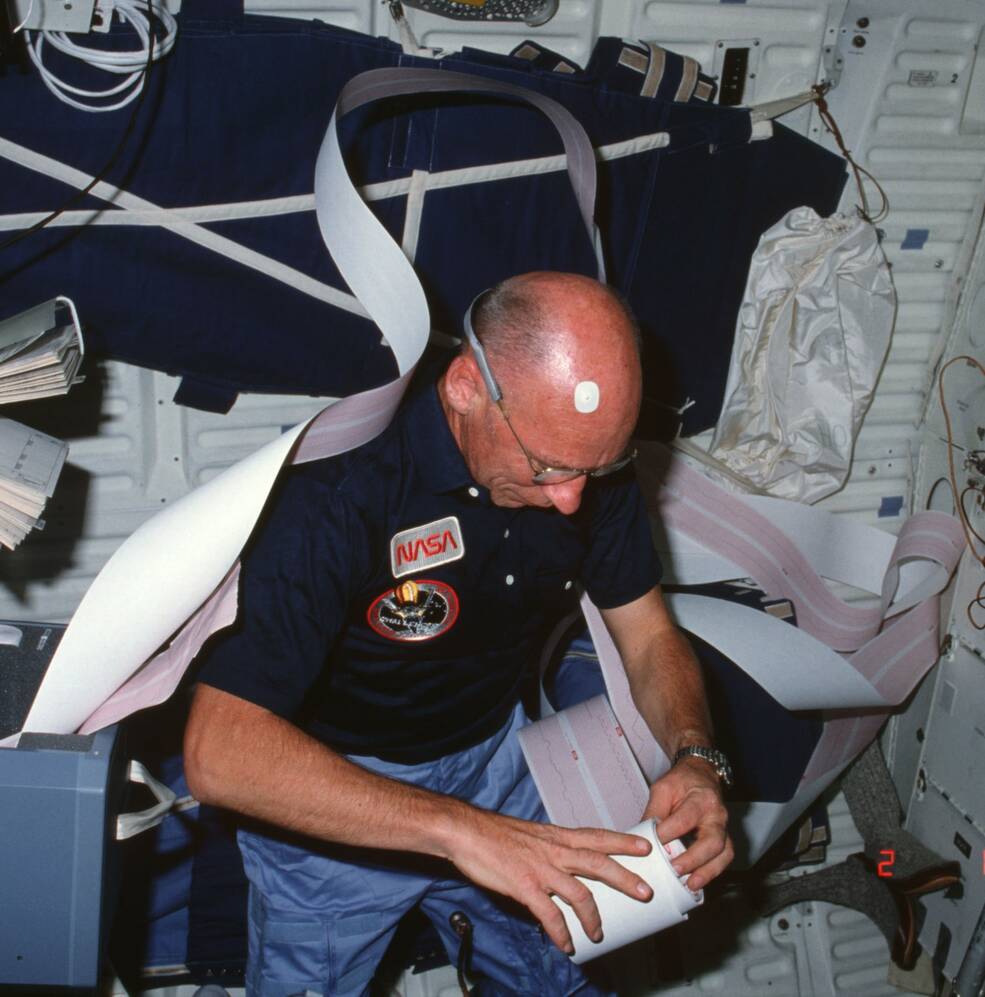

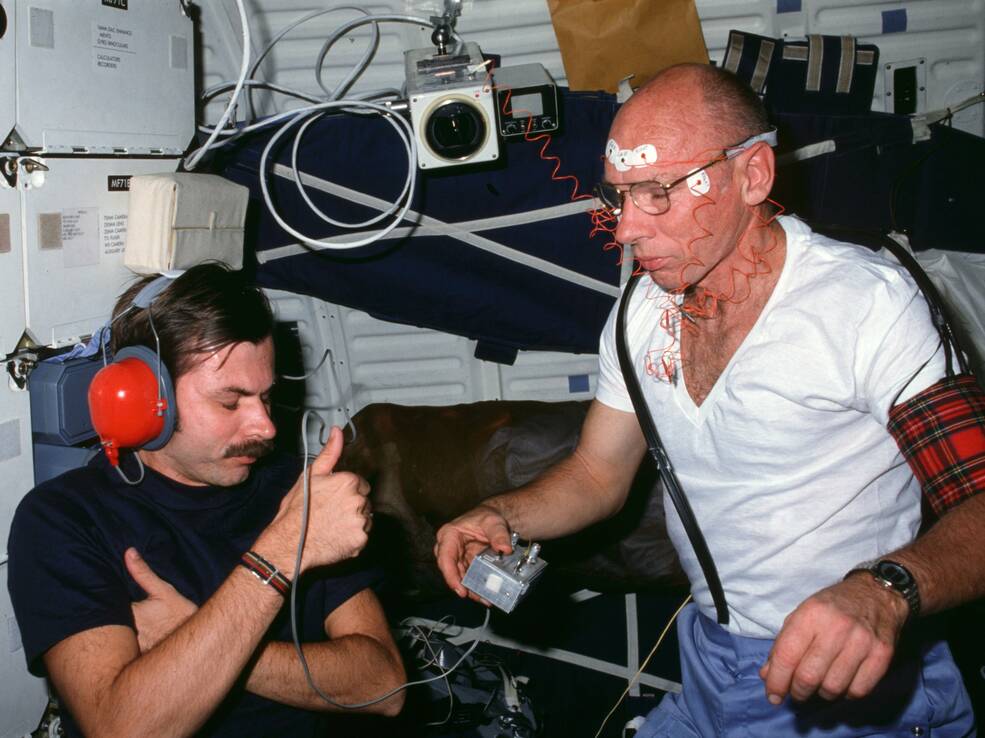

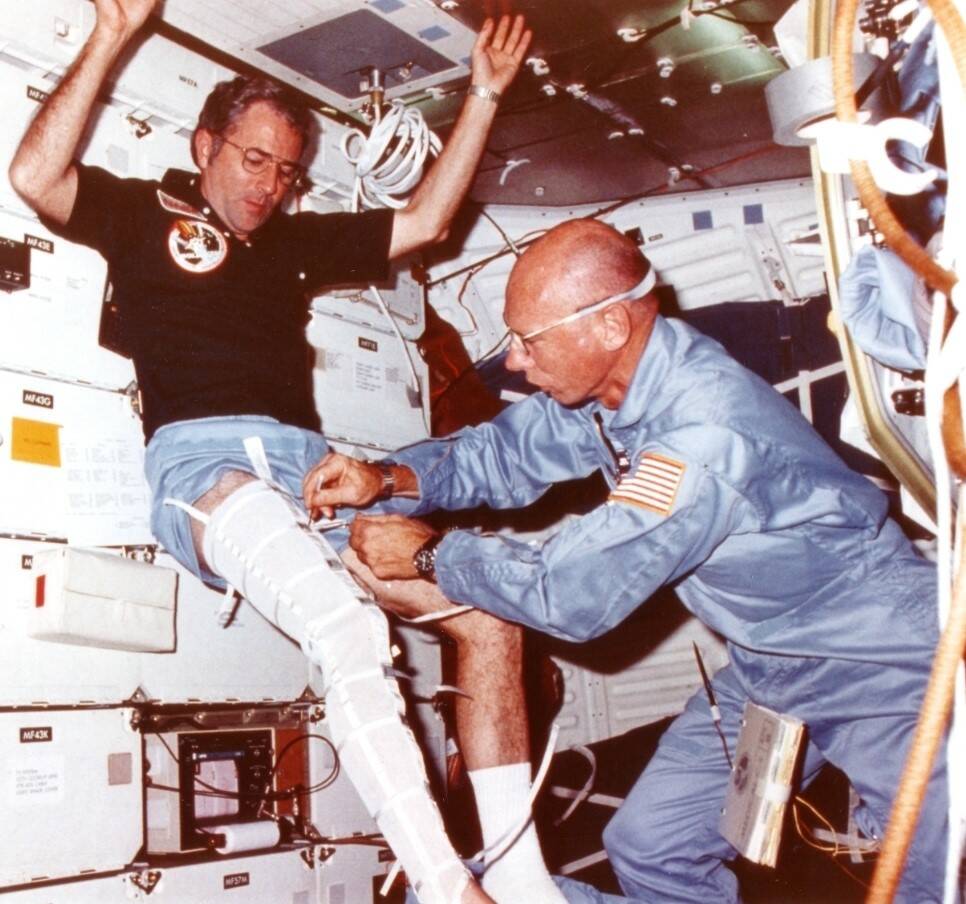

Left: Physician-astronaut Dr. William E. Thornton fully instrumented to conduct several of his inflight studies. Middle left: Thornton gathers a very long strip chart from one of his recordings. Middle right: Thornton conducts an audiometry or hearing evaluation on fellow crew member Dale A. Gardner. Right: Thornton measures leg volume changes on Richard H. Truly to document the headward shift of body fluids in weightlessness.

Left: Driven by the Agulhas Current, eddies swirl in the Mozambique Channel between southeast Africa and Madagascar. Middle: The Andes Mountains in Chile. Right: Fisher and Fisher – NASA astronauts William F. Fisher, left, and Anna L. Fisher, the first married couple to sit at the capsule communicator (capcom) console in Mission Control.

To begin Flight Day 6, the astronauts’ final full day in orbit, Mission Control played “Tala Sawari” performed by noted sitar player Ravi Shankar in honor of the release of the Insat-1B satellite. Brandenstein acknowledged the music by saying, “Thank you for that thoroughly enlightening cultural experience.” Throughout the day, the astronauts busied themselves with stowing items in preparation for reentry the next day. Truly turned on payload bay cameras and recorded the Earth during an entire orbit. He and Brandenstein tested Challenger’s flight control surfaces and navigation systems needed for entry and landing. During spare moments, the astronauts spent time looking at and photographing the Earth. Near the end of the day, astronaut Anna L. Fisher joined her husband Bill Fisher in Mission Control, the first married couple to serve as capcoms at the same time. Thornton provided his day 6 summary – the usual very busy day of data collection.

Left: During reentry, the orange glow around the shuttle caused by superheated plasma. Right: Space shuttle Challenger lands at Edward Air Force Base to end the STS-8 mission in the first night landing of the program.

Entry and landing day for STS-8 fell on Sept. 5, 1983, the Labor Day holiday. Mission Control awakened the crew with “Semper Fidelis”, written by John Philip Sousa and played by the Marine Corps Band, in honor of capcom O’Connor, a Marine Corps officer, then on console. Truly called down that the music had “everybody marching around up here.” The Gray Team led by Entry Flight Director Gary E. Coen, with Blaha serving as capcom, took their consoles to guide Challenger and its crew home to the first night landing in the shuttle’s history. The astronauts completed stowing some final items in the cabin, closed the payload bay doors, and Truly oriented Challenger with its tail facing in the direction of flight. Flying over the Indian Ocean, the astronauts fired Challenger’s two OMS engines for two and a half minutes to bring them out of orbit. Truly then reoriented the spacecraft so it flew nose first, presenting its underside covered with thermal protection tiles to take the heat of reentry. Challenger reached the first layers of the atmosphere at 400,000 feet altitude, and entered a period of communications blackout as the heated plasma surrounding the vehicle prevented signals from getting through. They emerged from the blackout at 278,000 feet, traveling at Mach 12, or 12 times the speed of sound. They crossed the California coast over Santa Barbara, and with the clear night could clearly see the lights of Los Angeles in the distance. Challenger dropped below the speed of sound, announcing its arrival with a double sonic boom, heard by observers who still could not see it in the predawn darkness. At 40,000 feet, Challenger intersected the heading alignment circle to make the sweeping left turn onto Runway 22 at Edwards AFB. An infrared tracking camera picked up Challenger, its nose cone still glowing hot from reentry. Brandenstein lowered the craft’s landing gear and Truly brought Challenger down for a smooth touchdown, the orbiter finally visible in the runway’s halogen lights. After rollout, he reported “wheels stop,” signaling that Challenger and its crew had safely arrived home after circling the Earth 98 times, in a mission lasting six days, one hour, nine minutes.

Left: The STS-8 crew disembarks from Challenger after its successful mission, ending with the first night landing of the space shuttle program. Middle: The STS-8 crew takes a congratulatory phone call from President Ronald W. Reagan. Right: Back in the office, the STS-8 crew debrief with the STS-9 crew.

Ground crews arrived to ensure that the astronauts could safely exit Challenger, and led by Commander Truly, they left the vehicle, their home for the past six days, walking down the stairs to the runway where NASA officials greeted them. They performed the traditional walkaround of the spacecraft and then took a bus to NASA’s Dryden (now Armstrong) Flight Research Center, where they received a congratulatory telephone call from President Reagan. They gave short speeches to an enthusiastic crowd who had gathered in the predawn hours to welcome them home. Then they boarded a jet bound for Houston, where a Labor Day picnic awaited them at JSC. By the next day, it was back to work for a series of debriefs with managers and engineers, and especially the STS-9 crew, eager to learn firsthand about the mission just completed. Meanwhile, workers at Edwards AFB towed Challenger to the Mate Demate Device to place it atop the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, a modified Boeing 747, for the trip back to KSC, where the duo arrived on Sept. 9. Once back in the OPF, engineers remarked that Challenger had returned in excellent shape, and they began the process to ready it for its next mission, STS-11 which NASA soon redesignated STS-41B in a new mission numbering scheme.

Enjoy the crew narrate a video about the STS-8 mission. Read Dan Brandenstein’s and Guy Bluford’s recollections of the STS-8 mission in their oral histories with the JSC History Office.

This article is dedicated to Dr. William E. Thornton, my first mentor at NASA.

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center