Muscle cars. Film cameras. Concert tees stuffed into bell-bottomed jeans. Rotary phones and 8-track tapes, TVs measured in cubic footage, crowded wallpaper. Slide rules and chalkboards and all-paper filing systems and vacuum tubes. It’s 1968, and we’re sending men to the Moon.

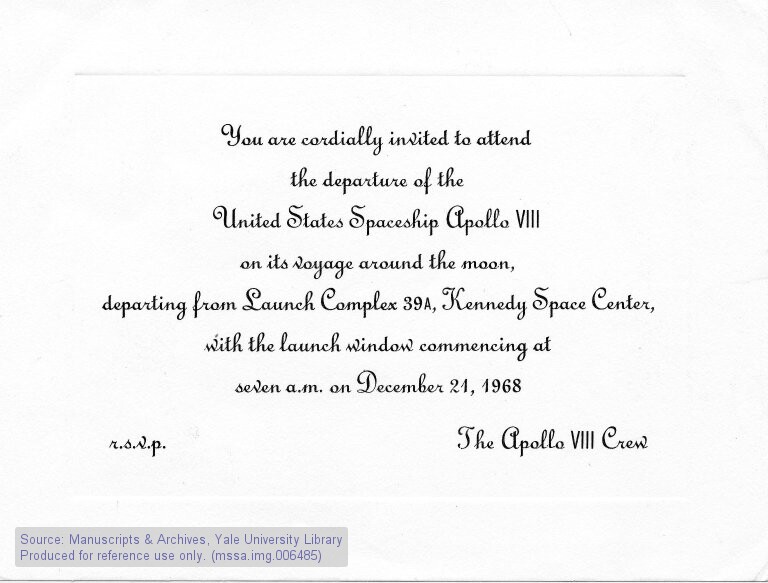

Apollo 8 was supposed to be a test flight, meant to simulate atmospheric re-entry from the Moon but never meant to go there. Hurtling toward Earth at 25,000 miles per hour is hairy business and NASA, having never done so before, needed practice. But then the USSR successfully launched two of its own Moon-shots (unmanned Zond 5 and 6) on the heels of President Kennedy’s call for men on the Moon by the end of the ’60s. It felt to most like a matter of time before America lost its space race for good.

NASA’s plan for Apollo 8 had to change.

Following a spark of ambitious vision, NASA reorganized, galvanizing a wild rush of fervor and late nights. In mid-August of 1968, astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and William Anders received a call telling them to cancel their holiday plans—they were going to the Moon.

By December, the three men were suddenly farther away than any human had ever been from our home planet, traveling faster and seeing more than could be seen in the entire history of life on Earth. From prehistoric cephalopods to T-Rex to our ape-like ancestors to Alexander the Great, no single pair of eyeballs had ever been so far from Earth’s gravitational influence until Dec. 21, 1968.

We were shooting for the Moon and we got there, sure enough, but the real triumph of Apollo 8 was beyond nationalism, beyond the tumultuousness of an age that catapulted these three men into the dark unknown. Apollo 8 was the fruition of ancient Chinese stargazers, renaissance dreamers and mid-century physicists. It was, above all, our first good look at ourselves, with the best possible perspective.

Today, leading up to the anniversary of one of humankind’s most audacious missions, we begin to celebrate 50 years of learning, inspiration, altitude and ingenuity not only about our nearest neighbor but also about Earth and where modern lunar exploration will take us next.

This is the first in a five-part series on the Apollo 8 mission and its influence on human exploration.

Related Links

- Part 1: To the Moon and Back

- Part 2: In the Beginning There Was Liftoff

- Part 3: The Far Side

- Part 4: The Return

- Part 5: Apollo 8 and Beyond – The Next Epoch