By Bob Granath

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida

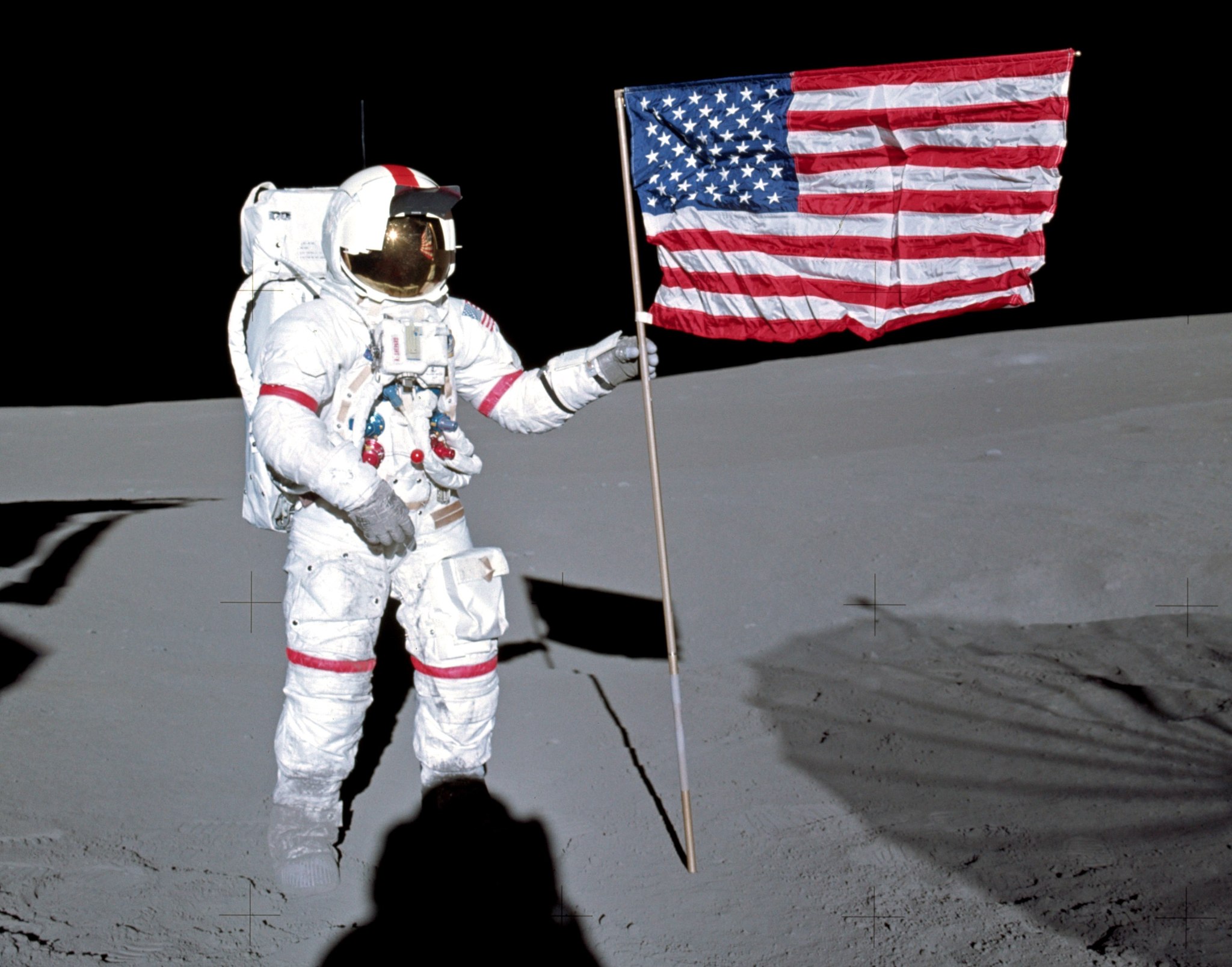

“It’s been a long way, but we’re here,” said Apollo 14 commander Alan Shepard as he stepped from the lunar module, or LM, onto the regolith of the moon’s Fra Mauro highlands.

When Apollo 14 touched down on the moon on Feb. 5, 1971, it was more than a 240,000-mile trip – it was a hard-fought return to flight for NASA’s Apollo Program and America’s first person in space.

Fra Mauro had been the intended landing site for Apollo 13 in April 1970. However, that mission became a struggle to safely return the crew when their Apollo spacecraft was crippled by an oxygen tank explosion.

Two days after the April 11, 1970 launch of Apollo 13, with the spacecraft approximately 205,000 miles from Earth, the astronauts heard a “loud bang.” One of two electricity producing fuel cell oxygen tanks in the service module had exploded. Damaged Teflon insulation on the wires to the stirring fan inside oxygen tank No. 2 allowed the wires to short-circuit and ignite the insulation.

The lessons learned from the lunar landing program now are helping the agency pave the way for the journey to Mars. As was the case during Apollo 14, NASA experts already are at work solving the challenges for human missions to the Red Planet.

In the nine months following Apollo 13, several modifications were made to the service module electrical power system, including redesign of the oxygen tanks and addition of a third tank.

After becoming the first NASA astronaut to travel in space on May 5, 1961, Shepard was grounded in 1964 by Ménière’s disease, a disorder of the inner ear that can affect hearing and balance. But, like NASA solving the problems posed by Apollo 13, Shepard found a way back.

A U.S. Navy aviator and one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts, Shepard’s condition prevented him from flying one of the Gemini missions. After surgery, however, he was returned to flight status. At age 47, Shepard would be the oldest space flyer to date and the only Mercury astronaut to walk on the moon.

Speaking about Shepard before the Apollo 14 flight, Kennedy Director Kurt Debus praised America’s first astronaut for his efforts to return to flight status.

“He’s an expert pilot and flier and he’s working very hard preparing for this mission,” Debus said. “I’m happy he’s getting the opportunity to go to the moon. I envy him.”

Joining Shepard were two first-time flyers from NASA’s fifth groups of astronauts, U.S. Air Force pilot Stuart Roosa, serving as command module pilot, and Naval aviator Edgar Mitchell, lunar module pilot.

Apollo 14 launched on a nine-day mission Jan. 31, 1971. Once in Earth orbit, Roosa commented that the crew was “thoroughly impressed” by the performance of the Apollo Saturn V vehicle that was assembled and launching from the Florida spaceport.

Soon after liftoff, though, the mission hit its first “bump in the road.”

After one and a half orbits of the Earth, the Saturn V third stage was fired a second time to boost Apollo 14 on its path to the moon. Roosa separated the command-service module, or CSM, — named Kitty Hawk — from the upper stage to turn around and dock with the lunar module, Antares.

The CSM had difficulty docking with the LM. Several attempts to dock took place for 1 hour and 42 minutes. At that point Mission Control recommended Roosa hold Kitty Hawk against Antares using its thrusters, then the docking probe would be retracted, thus triggering the docking latches. This approach worked.

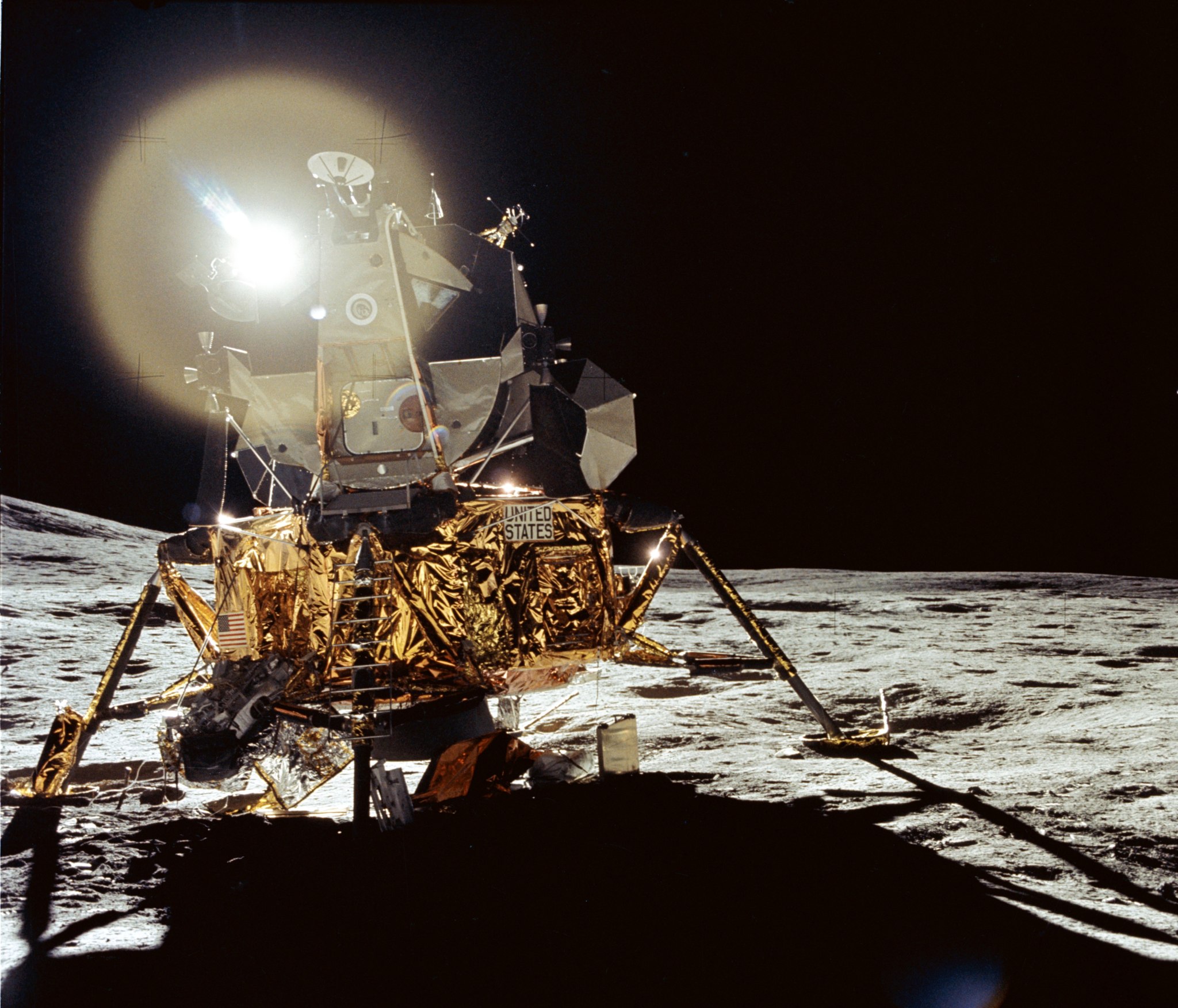

Apollo 14 arrived in lunar orbit on Feb. 4. The next day, Shepard and Mitchell boarded Antares and separated from Kitty Hawk in preparation for the landing. Soon after, the LM developed a problem.

First, the lander’s computer received an “abort” signal from a faulty switch. If the problem recurred after the descent engine began firing, the computer would respond as if the signal was real and initiate an automated abort. The ascent stage would separate from the descent stage and the LM would return to orbit.

NASA and the software experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology scrambled to find a work-around. They decided that the solution would involve reprogramming the Antares computer flight software to ignore the erroneous signal. The software modifications were radioed up to the crew. Mitchell entered the changes just in time, allowing the crew to be given a “go” to begin the powered descent.

“It’s a beautiful day to land at Fra Mauro,” Shepard said in response.

But a second problem soon occurred. The LM landing radar failed to automatically lock onto the moon’s surface, preventing the computer from being updated with crucial information on altitude and vertical descent speed.

Mission Control told Shepard and Mitchell to cycle the landing radar breakers.

“Okay, cycled,” Shepard said and he was told to check the radar again.

“Breakers, go, great, great,” he said as the unit began receiving a signal at about 18,000 feet, again, just in time.

As Antares pitched over and the two astronauts could see the lunar surface, landmarks and the landing point appeared precisely as planned.

“There it is,” Shepard said

“Right on the money,” Mitchell added.

Shepard then manually landed the LM with Mitchell giving a quick description.

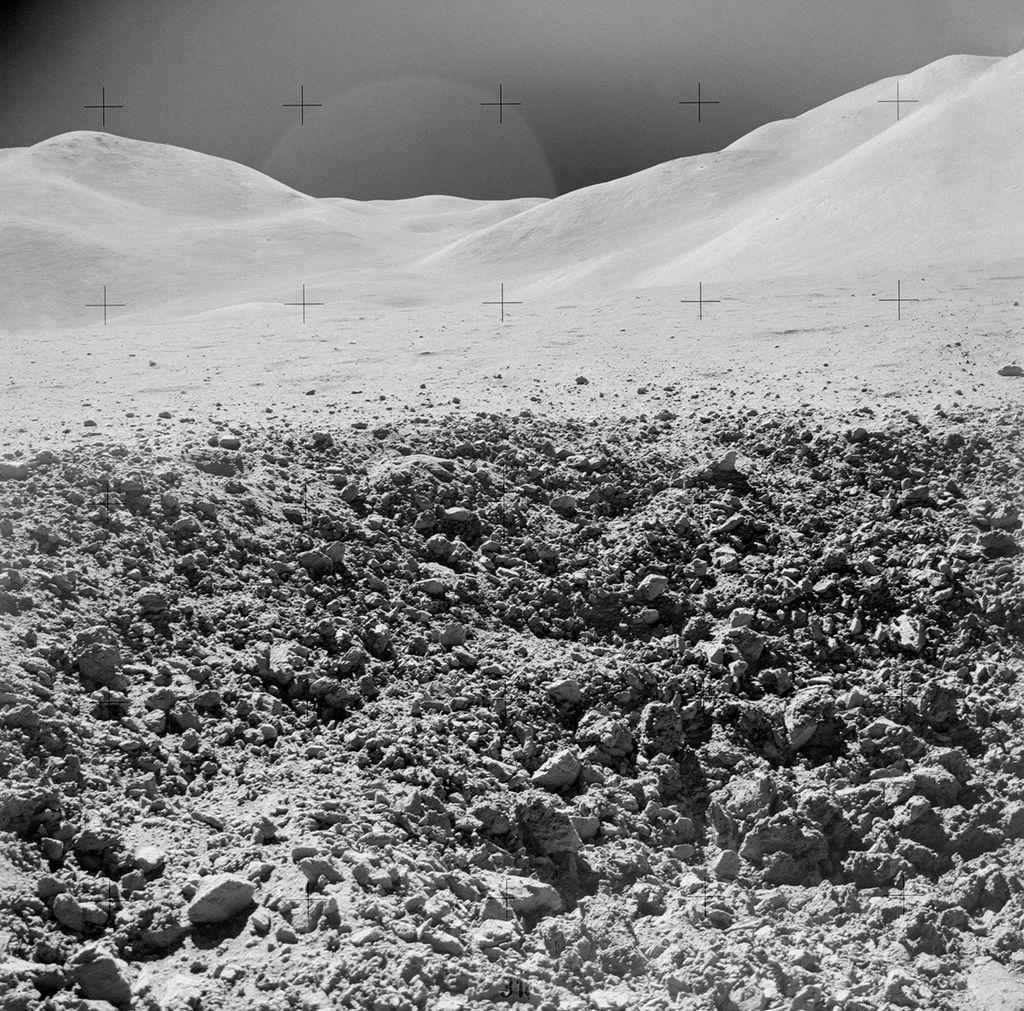

“It’s really a wild looking place here,” he said.

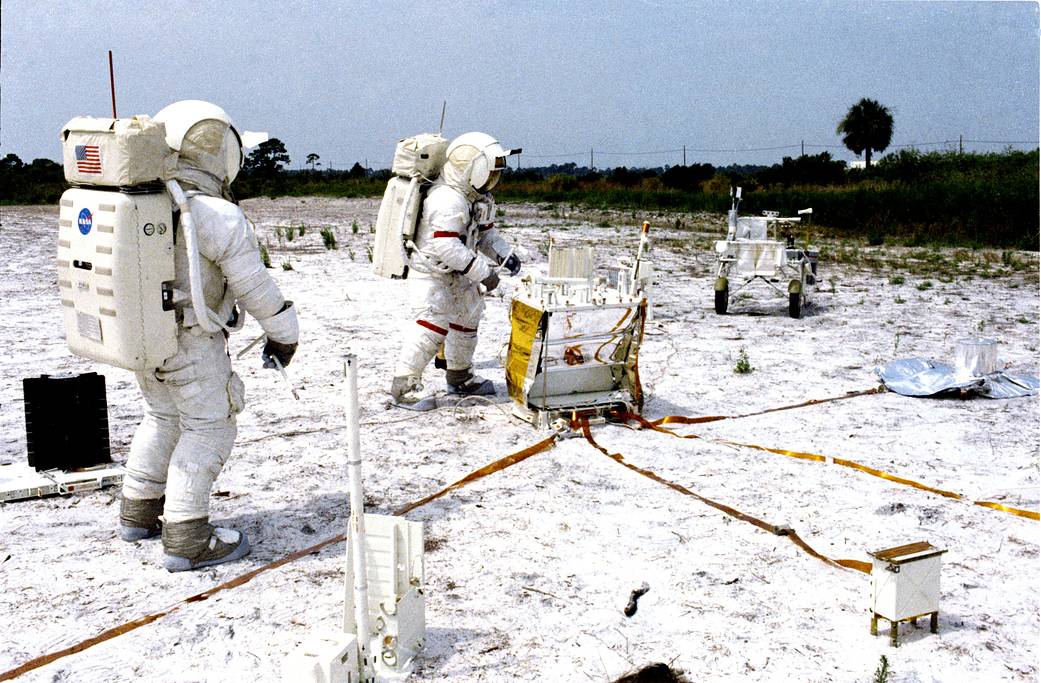

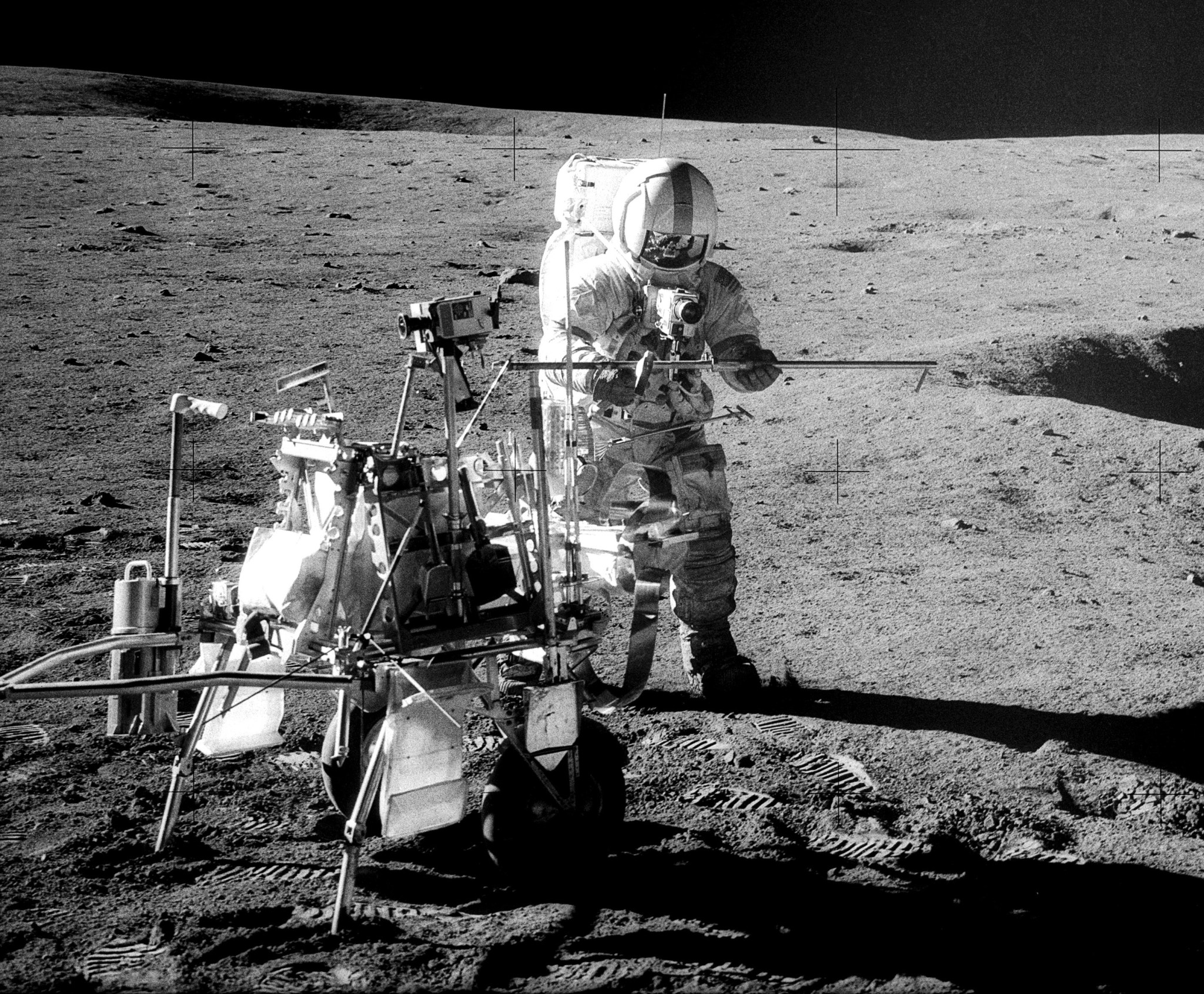

After landing at Fra Mauro, Shepard and Mitchell took two moonwalks. During the first, an Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package was set up and they used a modular equipment transporter, a pull cart for carrying equipment and rock samples they collected.

During the second traverse on the surface, the pair planned to reach the rim of the 1,000-foot wide Cone Crater. Mitchell noted that the terrain made walking more difficult

“We’re starting uphill now,” he said. “It’s definitely uphill.”

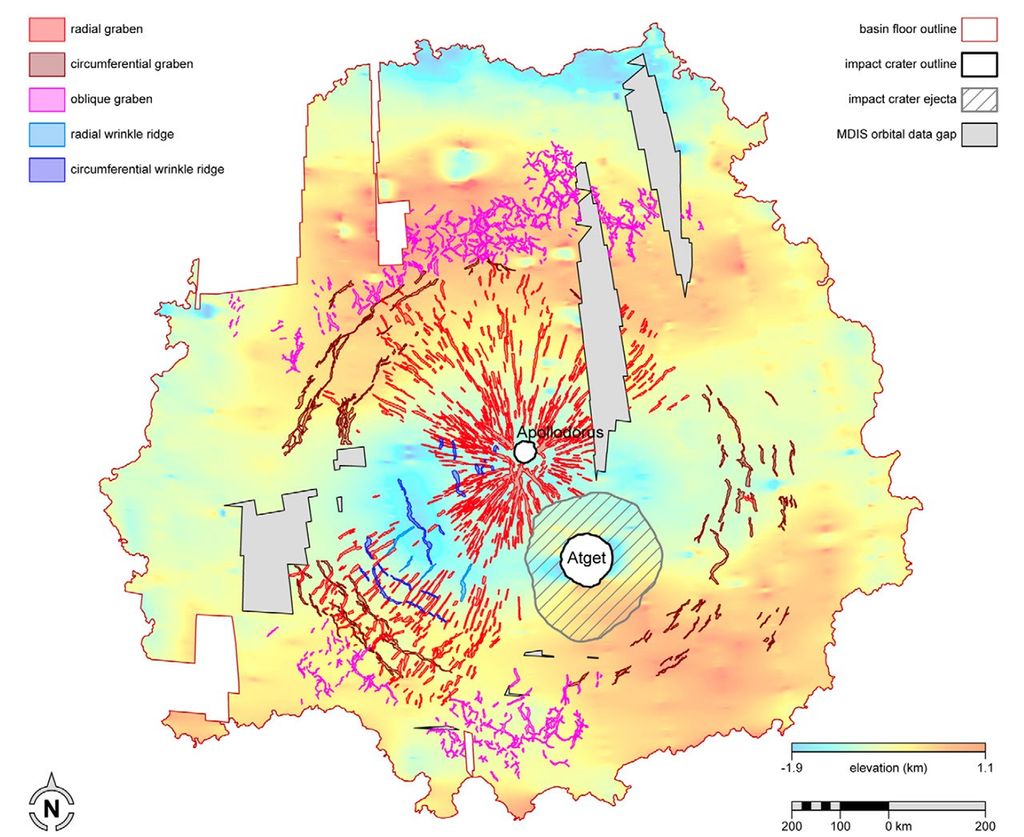

Stopping 150 feet from the rim of the Cone crater, they collected more rocks and soil. Scientists believed the samples could have originated from deep beneath the moon’s surface, ejected from the impact that created the crater.

As they walked along, Shepard referenced the powder-like soil that was kicked up from the moon’s soil and regolith

“Nothing like being up to your arms in lunar dust,” he said.

Scientists in the Electrostatics and Surface Physics Laboratory at the Kennedy Space Center are developing ways to mitigate the dust problem for future explorers. Emerging technologies, such as new space suits, also should aid astronauts as they travel to destinations such as Mars.

For Apollo 14, Shepard’s spacesuit was the first to use red stripes on the arms and legs and on the top of his helmet’s sunshade. This made it easier to distinguish between the commander and LM pilot on the surface. In some photographs from Apollo 12, it was difficult to differentiate between the two astronauts. This identifier was used for the remaining Apollo missions, spacewalks during space shuttle missions, and now are used on the International Space Station.

During Apollo 14, Shepard also set another space first. Toward the end of the second session on the surface, he stopped in front of the television camera and produced a makeshift golf club.

“Houston, you might recognize what I have in my hand as the handle for the contingency sample return,” he said. “It just so happens to have a genuine six iron on the bottom of it. In my left hand, I have a little white pellet that’s familiar to millions of Americans.”

An avid golfer, Shepard dropped a golf ball and took a swing.

“Unfortunately, the suit is so stiff, I can’t do this with two hands,” he said, “but I’m going to try a little sand trap shot here.”

Lunar dust flew.

“Hey, you got more dirt than ball,” Mitchel said.

“That looked like a slice to me, Al,” added spacecraft communicator Fred Haise, lunar module pilot on Apollo 13.

“Here we go again,” Shepard said as he took another swing. “Straight as a dime. Miles and miles and miles.”

During the two moon walks, about 94 pounds of rocks were collected, and several scientific experiments were performed. Shepard and Mitchell spent 33.5 hours on the moon, with almost 9.5 hours walking on the lunar surface.

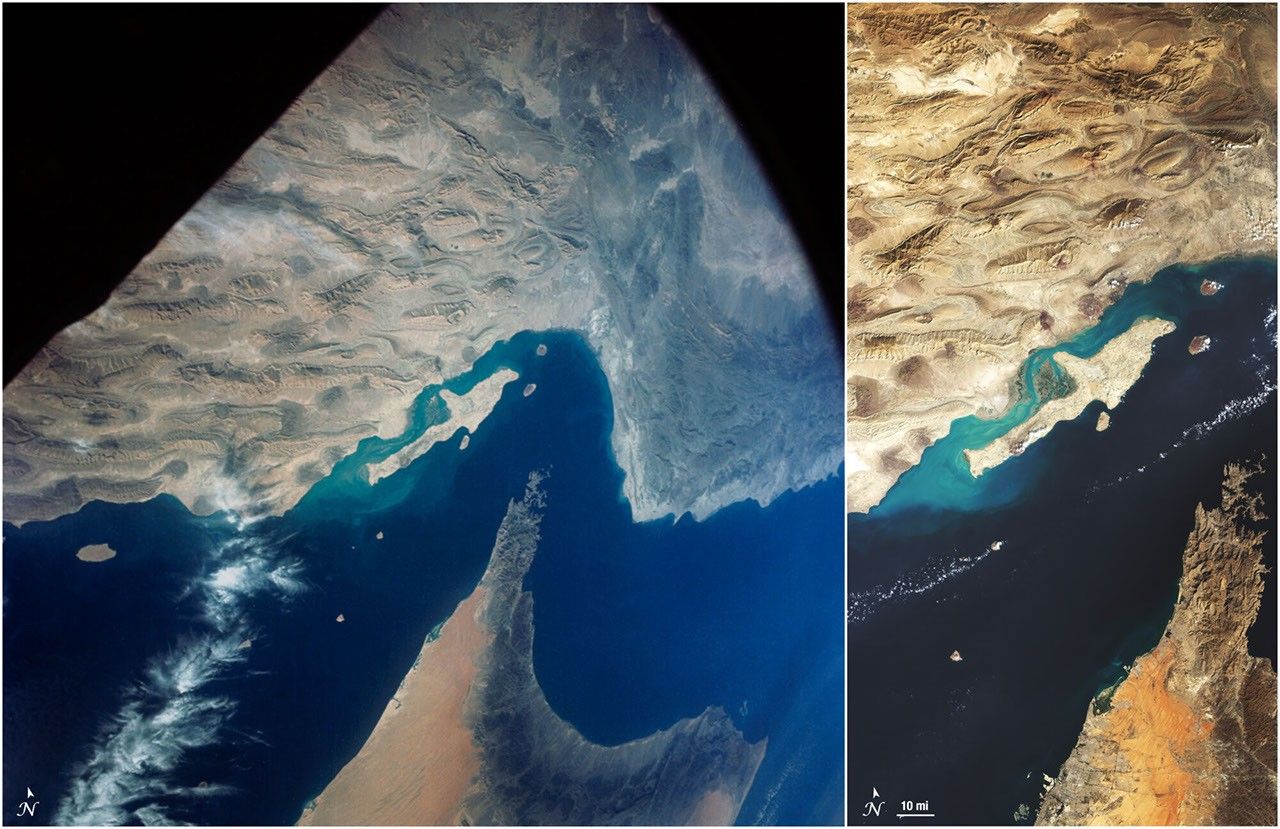

While Shepard and Mitchell worked at the landing site, Roosa orbited the moon aboard the Kitty Hawk. He performed scientific experiments and photographed the moon, including the landing site of the upcoming Apollo 16 mission.

Apollo 14 returned to Earth on Feb 9, 1971, splashing down approximately 760 miles south of American Samoa in the South Pacific Ocean. The astronauts were soon recovered by the crew of the USS New Orleans recovery ship.

On March 23, 1971, the Apollo 14 crew spoke to Kennedy Space Center employees in the transfer aisle of the Vehicle Assembly Building where their Apollo Saturn V rocket was stacked and checked out prior to rollout to the Launch Pad 39A.

We had a fantastic, resounding success on Apollo 14.

Alan Shepard

NASA Astronaut

“We had a fantastic, resounding success on Apollo 14,” Shepard said.

It was a triumphant return for both Shepard and Apollo.

During post-mission analysis, scientists determined that the Apollo 14 rock samples were found to be generally richer in aluminum and sometimes richer in potassium than other lunar basalts. The Apollo 14 basalts were formed 4 to 4.3 billion years ago, older than the volcanism observed at any of the other locations studied during the Apollo program.

“We’re extremely proud of Apollo 14, and each of you played a vital part in it,” Mitchell said. “As we watch the results come in from the scientists, we are more and more gratified.”

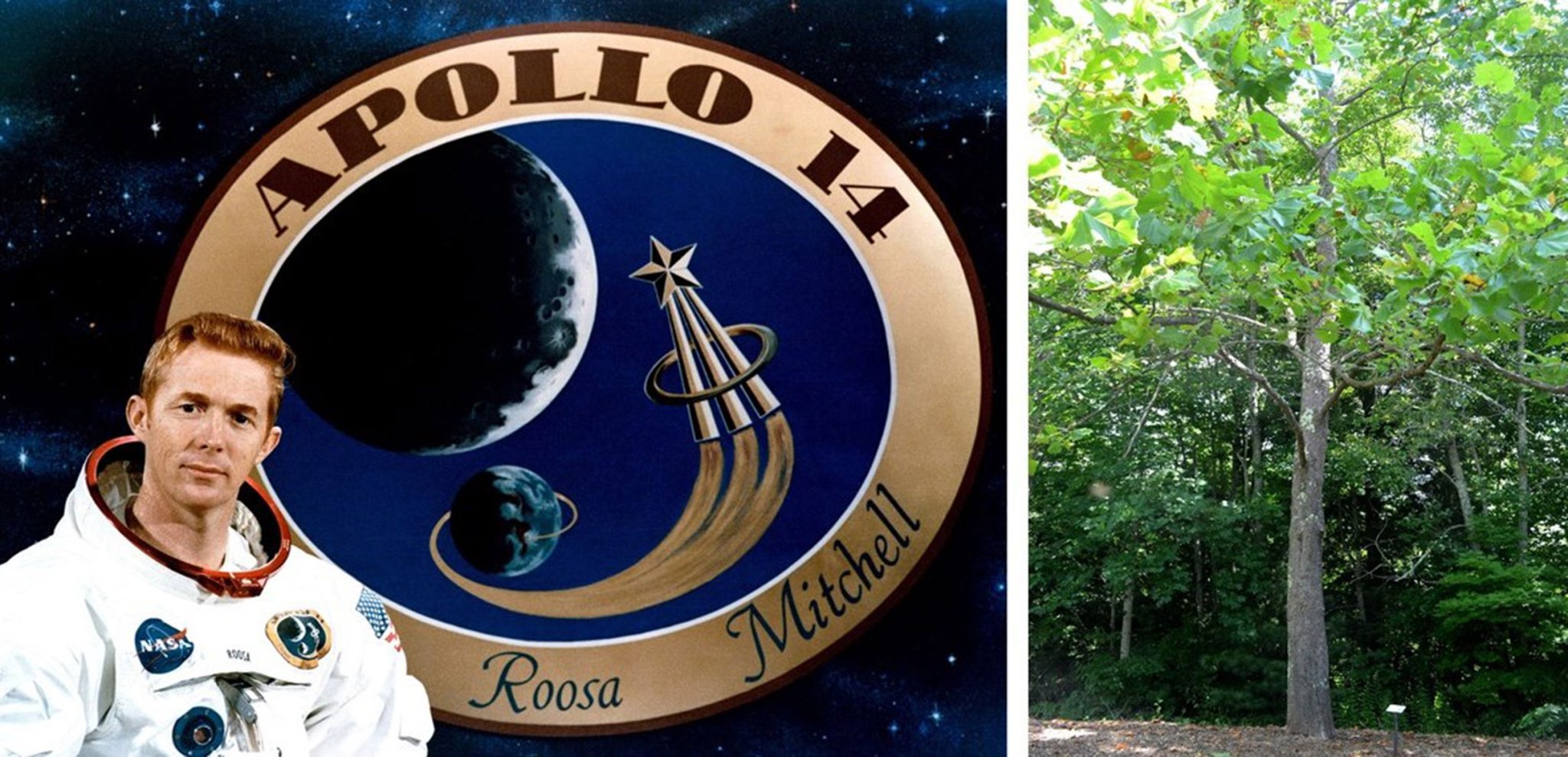

Stuart Roosa’s ‘Moon Trees’ Stand as a Monument to Apollo

When Apollo 14 command module pilot Stuart Roosa flew to the moon in 1971, he took along an unusual payload: tree seeds.

A native of Durango, Colorado, Roosa worked for the U.S. Forest Service in the early 1950’s as a smoke jumper helping fight fires. He later joined the U.S. Air Force, becoming a test pilot. In 1966, Roosa was one of 19 selected as NASA astronauts.

For the sixth mission to the moon and the third to land, Roosa packed small containers in his personal preference kit with 500 tree seeds, part of a joint NASA-U.S. Forest Service project. Seeds were chosen from five different types of trees: Loblolly Pine, Sycamore, Sweetgum, Redwood and Douglas Fir. The seeds were classified and sorted, and control seeds were kept on Earth for later comparison to those that had been exposed to the microgravity environment of space.

While mission commander Alan Shepard and lunar module pilot Edgar Mitchell landed on the moon, Roosa remained aboard the command module, Kitty Hawk, photographing the lunar surface, including future landing sites.

After return to Earth, the seeds were germinated. Known as “Moon Trees,” the resulting seedlings were planted throughout the United States, many as part of the nation’s 1976 bicentennial celebration, and around the world.

After Apollo, Roosa worked on the Space Shuttle Program until his retirement from NASA and the Air Force in 1976, the time when many of his trees were being planted.

Roosa died in December 1994. The Moon Trees continue to flourish, a living monument to America’s first visits to the moon and a fitting memorial to Stuart Roosa.