Think your home could use a bit of a sweep? Fret not – your hardwoods are nothing compared to the Moon. Its surface is so notoriously dusty that the desert here on Earth is the environment of choice for testing dust-related technologies bound for lunar missions.

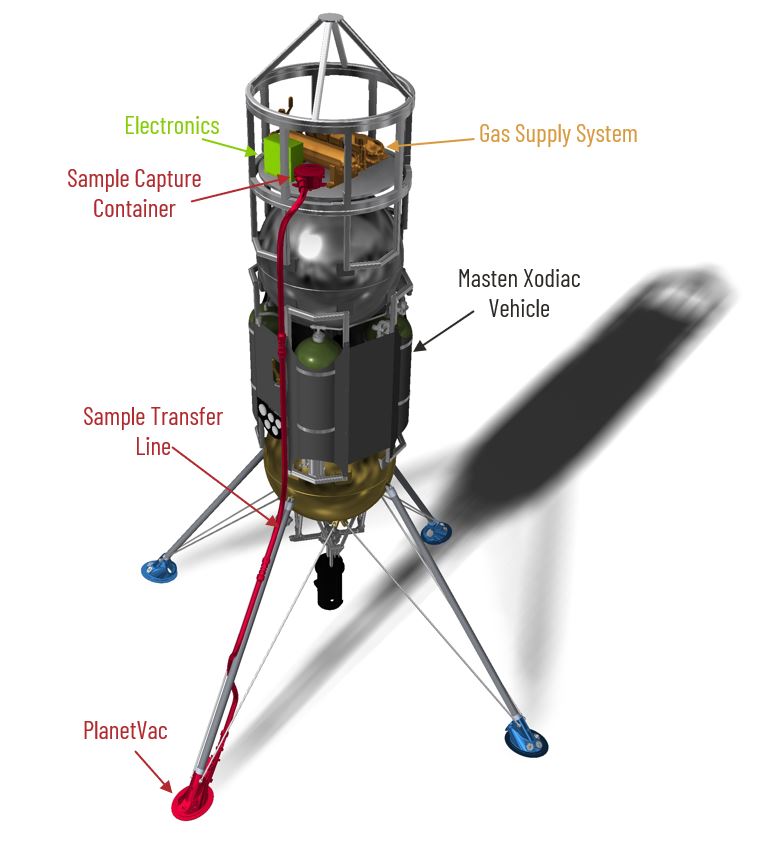

Two such dust innovations will be flight tested in Mojave, California, on a Xodiac vertical takeoff and vertical landing system – which functions much like a lunar lander – from Masten Space Systems. These tests are facilitated by the Flight Opportunities program, part of NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate. The goals: to help researchers advance a sensor designed to address the hazards of ejected dust, rocks, and other particles produced by rocket plumes as well as a device for collecting lunar dust and soil for analysis.

Measuring the dust

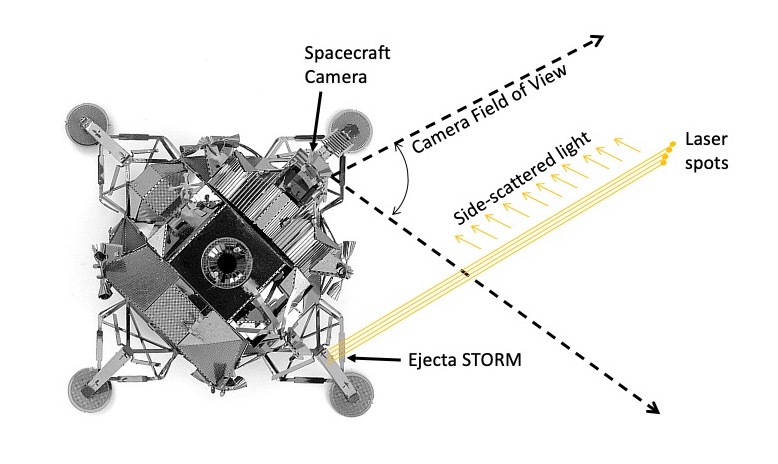

“When a vehicle lands on the Moon, it shoots out a lot of ejecta at high velocity, including dust as well as larger gravel and rocks,” said Philip Metzger, a planetary physicist at the University of Central Florida in Orlando and principal investigator for the laser-based Ejecta STORM sensor on the upcoming flight. “This can cause widespread damage from sandblasting spacecraft surfaces and solar cells to actually striking and breaking optical sensors or other instruments.”

Metzger has been studying the effects of lunar ejecta for more than 20 years, including at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where he contributed to recommendations for protecting the Moon’s Apollo heritage sites from sandblasting effects.

“Having ejecta sensor data from actual lunar missions can help us improve those recommendations and will also help us protect the new spacecraft we’re sending to the Moon and even spacecraft orbiting around it – all of which is important not just to the U.S. but to the international space community as well,” Metzger said. “And then we can develop physics equations that are truly predictive to inform mitigation strategies.”

The upcoming flight test is a step in that direction. Metzger and his team will mount their sensor to Xodiac, with simulated lunar soil placed beneath it. The sensor will shine four lasers into the blowing dust cloud, measuring the amount of dust, the erosion rate of the soil, the sizes of the particles and their distribution, and other factors. Those measurements will then be used in computer modeling to provide predictions for bigger or smaller landers under a variety of landing conditions.

Metzger said that flying the low-mass sensor routinely on lunar missions could also help scientists monitor the Moon’s environment for changes over time.

“As we measure the dust, we’re also able to quantify how much gas from rocket exhaust gets trapped in the lunar environment,” he said. “And as more and more missions land on the Moon, this will be important in order to protect the lunar environment for scientific purposes.”

Metzger said the test facilitated by Flight Opportunities is a critical step toward the goal of a lunar mission where they will be able to take measurements on the Moon itself.

“When you do a lunar mission, you really get one chance – a period of about 30 seconds – to get the measurements you need,” he said. “So, you don’t want to waste that. You have to do field testing to make sure you’ve validated all the different aspects of the sensor that you can.”

Collecting the dust

Dust on the Moon is not just a hazard – it also presents scientific opportunity. In fact, researchers want to collect some of that surface dust, called regolith, for analysis. This is the goal behind the second technology flying on the upcoming flight test: PlanetVac from Honeybee Robotics, headquartered in New York City.

Previously flown on Masten’s vehicle in 2017, PlanetVac attaches to the leg of a lander and uses gas to initiate suction, transferring a surface sample through a tube and depositing it into a container that can be sent back to Earth for analysis. The device has been selected to go to the Moon on a future flight through NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative. The payload will also be part of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Martian Moons Exploration mission in 2024.

While the 2017 testing proved the technology’s ability to successfully collect more than 300 grams of simulated regolith (about the size of an orange), the upcoming flight goes a few steps further. First, whereas the previous test involved a sample container located very close to the lander footpad, this time researchers want to demonstrate the ability to transfer the sample to a container located several feet above the device.

“This will show that the technology is capable of even more than it would likely need to do in a lunar mission,” said Luke Sanasarian, mechanical engineer and Honeybee’s project lead for the upcoming flight. “If we can show that we can deliver a sample in this scenario, then we buy down even more risk for the lunar mission.”

Second, Honeybee is taking advantage of the dust clouds created for the Ejecta STORM testing to evaluate PlanetVac’s efficacy in collecting a sample after the surface has been scoured of loose regolith – something they did not look at in the 2017 tests.

“Previously, we completely blocked the rocket plume to prevent it from disturbing the regolith, because the amount of disruption given Earth’s atmosphere is much more than what we’d see in the vacuum environment on the Moon,” explained Sanasarian. “But now we want to allow for some disturbance of the surface soil, to a degree similar to what we’d see in a lunar mission. This gets us even closer to what the device will encounter there.”

Sanasarian said that this iterative testing – where researchers are able to evaluate certain aspects of a technology, make refinements, and then fly again to validate other parameters – has proven extremely valuable in preparing PlanetVac for the commercial mission, scheduled for 2023.

“Being able to do this second test in a new configuration is not only expanding our understanding of how the technology works, but it’s also expanding the potential missions that it could be a part of,” he said.

Flying the University of Central Florida and Honeybee technologies together will also provide more data than either team would have had flying alone. In particular, the university team’s measurements may help Honeybee better understand just how much surface soil can be disturbed while still allowing for a successful sample collection.

“Having their data to help us understand how much dust is being kicked up really makes for a beneficial complement to our testing as well,” said Sanasarian. “And of course, that just adds even more value to the flight for everyone involved and for the NASA missions that will benefit.”

By Nicole Quenelle

NASA’s Flight Opportunities program