Name: Christian Taubenberger

Title: Office of STEM Engagement Intern

Organization: Code 615, Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory, Sciences and Exploration Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

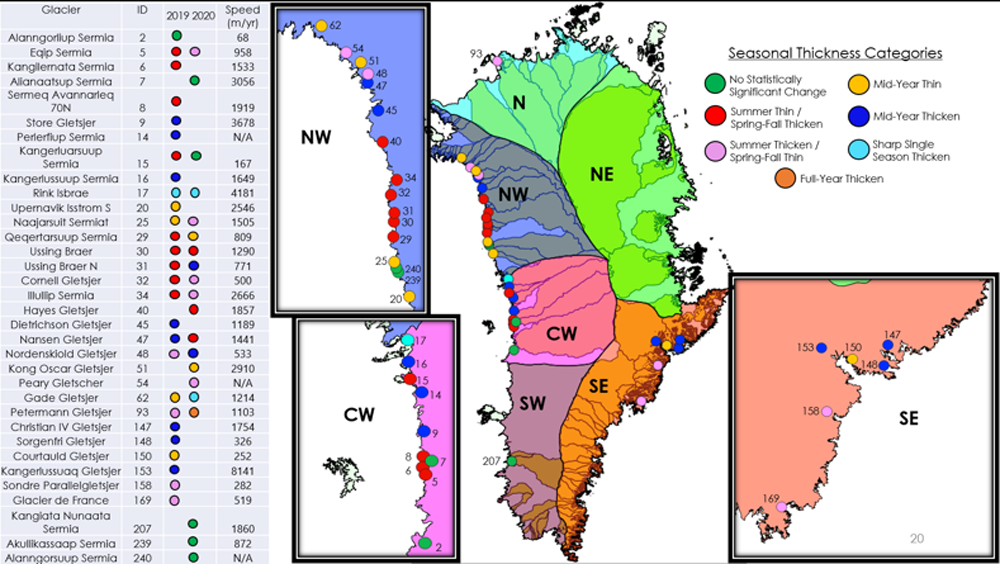

I worked as an intern with the Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory through the summer of 2020 and then spring of 2021 on the same project. I looked at seasonal thickness change across different outlet glaciers throughout the Greenland ice sheet. In summer of 2020, I started with just a couple of glaciers. Then we extended that in the spring to continue using the ICESat-2 satellite and its ATLAS instrument ATL06 data product to look at the seasonal thickness change across the entire ice sheet, looking at 63 different glaciers. I was very lucky to work on a project that had a lot of different directions we could go in, and we were able to adapt to wherever the project was taking us. I had a lot of freedom to work on the best project I could within the time frame.

In my research, and throughout the entire internship project, I was able to look at brand new data that we’re getting from ICESat-2 and get a first look at what the data product can do across the first few years of data collection. And I was able to find a way to communicate that not only to my lab and my mentor, but also turn it into a paper that we’re able to present to the larger public.

What is cryospheric science, and what does NASA’s Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory study?

In a broader sense, cryospheric science is looking at Earth’s ice cover, including glaciers and ice sheets, and both land ice and sea ice. The Greenland marine-terminating outlet glaciers, which are glaciers that flow down to meet the ocean, are specifically what I worked on. There are tons of projects operating out of NASA’s Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory. A lot of them revolve around using NASA’s new satellite, ICESat-2, that launched in 2018 to look at a multitude of different aspects for land and sea ice.

Why did you want to intern at NASA?

From a young age, I very much wanted to work at NASA and, in a very broad sense, research unique elements of our planet. But specifically, I went through my college education looking at various types of science in different fields. I ended up getting an internship here at NASA in the summer of 2020 and got my first look at cryospheric science, and I loved it. So I ended up getting a second internship here with the same mentor, Dr. Denis Felikson, whose support and expertise really helped get the project to where it is today. Throughout my internships we were able to expand my knowledge and the scope of the project in a way that could just continue to grow.

What was your favorite part of your internship? What was the most challenging part of your internship?

My favorite part was learning all this information that I originally had very little knowledge about. More specifically, another aspect of that would be seeing the results of all the work across these two internships come into light and result in a paper. I think it’s incredible that over just two short stints at NASA, we’re able to take someone like me who is not very experienced and turn them into someone who is published in this field.

The most challenging part was that I started in the summer of 2020 with very little idea about how to code in Python, which is a programming language, and that was a big part of the project. It took a little while to get up to speed.

Can you explain what it was like writing a paper as a NASA intern? What elements of your research were included in your paper?

This was actually my first published paper other than what I’ve done for my thesis. And it was a great experience because not only was I still working on the project as an intern and figuring out the science behind it, but then to take that project and turn it into something written and publishable was really cool. And to get the help of my mentor, a NASA expert, was great.

One important aspect to highlight is that this was a first look at a Greenland-wide study of glacier’s seasonal dynamic thickness change. The overall main purpose of the paper was to show the results that we are getting from ICESat-2, specifically looking at the ATLAS ATL06 dataset. From there, we can see if our results can be used for other projects in the future, like improving model constraints. There have been various studies that have looked at specific glaciers on a seasonal scale, but to get this broad grouping of glaciers and look at the nitty gritty, seasonal timescale responses across many different regions is something that we weren’t able to do before ICESat-2.

Where is your paper under review to be published?

The paper is currently under review in the journal The Cryosphere. (The paper was open for discussion, comments, and questions in mid-July). As an author, I and my co-authors respond to those questions. It’s an interesting way to put it out to the public a little bit earlier, while still undergoing the time it takes to put it fully under peer-review.

Who did you work with on the paper and how did they contribute to your experience at NASA?

My internship mentor and co-author on the paper, Dr. Denis Felikson, helped me the most. He was very supportive of everything I did and was able to guide me down a path that the project would develop in a fruitful way while also leaving it open to what I wanted to study.

Alongside Denis, I worked with many different scientists in the Cryospheric Sciences Lab. The lab chief, Thomas Allen Neumann, is another great scientist who is another a co-author on the paper. He helped find the funding for the project and helped make sure that the project tied into the ICESat-2 mission at large.

What is your educational background?

I went to George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, for both my undergraduate bachelor’s degree, as well as my master’s degree. My undergraduate degree was in biology, with a minor in astronomy. I got a look at Earth science through different electives and core classes and, from there, ended up doing my master’s in Earth system science.

Will you continue to study cryospheric science?

Yes. I am going to hopefully be continuing cryospheric research, looking at what I started with here in the NASA internship program. I will be attending the School of Environmental Health and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, specifically working toward the Geography and Environmental Engineering PhD program. The general idea is to continue this research with ICESat-2, looking at seasonal change and various aspects of glaciers, maybe taking different datasets into account, such as velocity and terminus distance change. I’m also looking into studying how ice crevasses impact changes.

Why did you transition into studying Earth System Science?

I took some geology classes during my undergraduate studies, and I found that I really liked those courses. Everything I was learning about the planet was fascinating. And I just wanted to learn more about how everything functions at large, how the different spheres (atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, lithosphere, cryosphere) of the planet interact with each other, and how we as people impact the planet. It wasn’t a massive leap to go from environmental biology into studying Earth science, but it was great to feel like I was narrowing down what exactly I wanted to concentrate on, even more so having found my niche here in cryospheric science!

What advice would you give for NASA interns?

My advice would be to continue working diligently. Even if you’re stuck on something, that’s okay. You can talk to your mentor and maybe they’ll try to find a different way around or maybe pivot your project level in a different direction. Because the overall goal of this internship is to help introduce you into work experience in your field and assist you to become a better scientist, or whatever your internship is in.

To read the paper that Christian Taubenberger authored while interning at NASA, go to: https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2021-181

By Emily Fischer

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.