Where are you from?

That’s always a complicated question, even when I’ve just met friends. I was born in Southern California. We moved when I was 10 and I lived in Missouri for 7 years, and then the East Coast. We moved in the middle of high school to Rhode Island and I kind of finished all of my college, grad school and everything on the East Coast. Then once I finished grad school I came here for the postdoc and that’s how I got back to California.

What got you into Space Sciences? How did you get interested in astronomy?

It was a long time ago! I guess it’s sort of cheesy but I saw this movie Contact, the one with Jody Foster, and that really changed me. I was probably about 14 when that came out, it hit me pretty hard, and I just felt, at that time, and still kind of do, that there is really almost nothing that I could do that would be more meaningful to me. Just astronomy and thinking about the universe is a huge passion and I think it’s so important for everyone to learn about. I just love it.

What is your educational background?

Right after I saw that movie, my dad got me this book that was kind of a younger, more accessible version of A Brief History of Time, and in that book, they introduced the concept of spectroscopy. I was just amazed that you could look at a light, at a star far away, and see this particular pattern that represented what that star was made out of, just by looking at little peaks in a rainbow, and I was just floored by that. That’s what kind of got me into it. I knew I wanted to do astronomy, and in high school, I was trying to take all of the science classes.

I did start doing physics in school but my very first summer internship when I was in college, was working in an ice lab in Alabama, similar to what we have here, where we were making interstellar planetary ice analogs. I was looking at spectra all day long, making ices in a tiny little vacuum chamber and it was the coolest thing for me, I had a blast. I worked with Perry Gerakines, he is now a very successful scientist at Goddard. I met, as a young scientist, a whole bunch of people through him. That’s what I came here to Ames to do, that similar kind of laboratory work on ices in the interstellar medium. And I’ve always been drawn to spectroscopy, different versions of spectroscopy, as I went through school.

Was that also your pursuit as a postdoc?

Yes. My postdoc here was working with Andy Mattioda; we were looking at PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) in an ice chamber and exposing them to radiation. I also actually came here to work on the O/OREOS mission, which was sending little chemical samples up into space to see how they really evolved out there, when subjected to that kind of radiation. That was how I got started at Ames too.

What are you doing now and what is most interesting about your role here at Ames?

Things have changed a lot since I got here. I was doing lab work, and just kind of getting to know people at Ames, hearing about all the different projects and stuff. I had friends who were working in all sorts of different things. And as my postdoc was ending, I realized that I had this opportunity, to get more involved in some mission work, which has kind of always pulled me. But it was hard for me to see the path there, how to switch from “pure science” after going in that direction for so long, to “applied science.” I felt I needed to get more involved in instrumentation and just general mission work. I had an opportunity to work with Tony Colaprete on an instrument.

I first started working on the LADEE mission. We were looking at data from an Ultraviolet and Visible spectrometer, looking at dust in the exosphere of the moon, so that was one of my first experiences with NASA missions.

Then I started working on developing new instruments with that same team for other lunar missions. Now my work is primarily in instrument development, which is really fun for me personally because I work on a team of people with a huge variety of expertise, and I really love teamwork so it’s great, to all be depending on each other, relying on each other to try to build this instrument. It’s a little bit less solitary than I’ve found science-only tends to be sometimes, so this is really good middle road for me, to have the science and still be able to work on spectroscopy, which I still love, and then building instruments to work for mission stuff. And actually, I would say that working in engineering stuff has made me a lot smarter about science, too.

How do you help support Ames’ missions? How is your work relevant to NASA’s exploration vision?

The instrument that I work on right now, the primary one is called NIRVSS; that’s a hilarious acronym — it stands for Near Infrared Volatile Spectrometer System. The “volatile” is the key part, and what it’s meant to do is go to the Moon. Originally it was designed to go to the poles of the Moon, where there is strong evidence for ice (volatiles!) in the permanently shadowed regions in the craters at the pole. Specifically, water ice. Water ice is obviously really important to NASA for a whole bunch of reasons but in terms of the Moon, if you’ve seen The Martian, you understand that water can be converted into rocket fuel, so being able to find water at the Moon and create your own fuel at the Moon, allows you to launch from the Moon, and with that significantly lower gravity, it’s an easier launch. Of course you have to build up all of the infrastructures to support that easier launch, but eventually, there is a cost saving there. You can also use the water for a Moon base. All of that used to sound like kind of a pipe dream in my mind, but I think I might actually be able to witness that in my life, that there will be people on the Moon using water that they found on the Moon, so that would be really cool.

What’s a typical day like for you?

I have meetings. I have to meet with the team and make sure that all of our plans are aligning. Basically my job now… I’ll give you an example, we are about to take on this long environmental test campaign for our instrument NIRVSS, and that means that we are going to expose the instrument to extremely cold and extremely hot temperatures, under vacuum. We are going to shake it on the vibe table, make sure it can survive the vibrations and jerking around at launch, and we are going to do all of these tests here, coming up in about a month and a half.

My responsibility is to plan all of those tests, make sure that we vibe the instrument at the right levels, not too high, we don’t want to break anything. Well… if we break something we want to make sure we’re breaking it at a launch load (laughs), make sure it’s something that the instrument might actually experience. And we want to know if it’s going to break because then we need to fix something to make it more robust. I’m responsible for running the vibe test and thermal-vacuum test, and writing all the test procedures and stuff for that, and trying to keep the instrument safe, follow NASA rules and prepare the instrument for a launch. NASA is putting together a new lunar program; we are hoping we can get our instrument on one of the first landers or rovers.

What do you like best and least about your job?

Why don’t I start with the least so I can end on a high note? It’s tough to get funding for your work and I guess that’s the hardest part of my job, writing the proposals. Trying to convince your upper-level management that they should invest in your idea because it’s going to go far, and “I’m going to bring the Center money,” “we are going to build something that the Center can support as a mission”. But all of these things require you to argue and make a solid case, and even when you do a good job, most of the time it doesn’t work. But I’ve been feeling pretty optimistic lately, things are going a little better than they have gone in the last couple of years for me. More of my recent proposal work has been successful, so maybe I’ve found a groove.

The best part though about my job, though, is just the people. Honestly, the people that I work with, I adore them. It sounds cheesy but the team that I’ve been working with for this instrument, some people come in and out, but there has been kind of a core of us. It feels like a family at this point and I love working with them. That’s my favorite part.

What’s the most unexpected result that has come out of your work so far?

One thing still remains a bit of a mystery. When we were working on LADEE data- that’s the Lunar and Dust Environment Explorer- this is the one where we were looking at dust in the lunar exosphere. We published a paper about what we detected, and basically what we believe we’ve seen is evidence of a very large extended cloud around the moon of very, very small grains, much smaller than we expected. And it appears as this kind of “nanodust” cloud, we’ve called it. It kind of wobbles around the moon in response to stuff like solar wind and meteor streams. But the results are confusing, and it’s tough to jibe our results with some of the results of the other instruments that were on the mission. It’s one of these things where you have the data and you do everything you can to remove this possibility or that possibility for explaining away the unexpected data. We did everything we could think of, and this signal was still there, so there is this kind of mysterious spectral signal that looks like it could be nanodust around the moon. I think that was probably a surprising thing for all of us, but also kind of frustrating because it still feels like a bit of an open question. We have the data, it’s there, and we can’t explain it away, but it’s hard to kind of fit it into the big picture of the Moon’s exosphere, so that’s probably one of the most surprising, mysterious things. That’s how science goes though – more often than not, you’re left with even more questions!

Tell me about a favorite memory from your career.

I’m still pretty proud of this proposal that I worked with the Mission Design Center here at Ames to put together this mission concept called Aeolus. It’s a Mars orbiter mission. It’s the brainchild of Tony Colaprete — we kind of put together this mission concept with a great team at the MDC, the Mission Design Center. I hadn’t worked with the MDC much before, but they were really terrific. We put the concept together with a lot of work, late hours, a great base concept, and we got funded by NASA to further mature the concept. So what ended up happening was that a hundred different concepts were sent in to NASA, and NASA was going to select a few of them to give a little bit more money to do an extra study, and we were one of ten selected. And you know, for the most part, we were a very young proposal team, and I think we surprised people, to be honest, that we could get the job done. I’m just still very proud of that. And we’re continuing to pursue this concept; it’s gaining some traction here on Center, and in the Mars community. That’s probably my favorite memory so far, celebrating that win with them. I’m sure there will be more awesome stuff to come.

Who inspires you?

So many people inspire me in different ways. Today, I would just say brave women, and not always the female scientists. Women from all walks of life. This is tough because I just feel political now. How can I answer this without being political? Brave women. I’ll just leave it at that. There are several here at Ames who inspire me on a regular basis.

If you could have your dream job, what would it be?

Oh man, this is it! There have been a couple of times when I wish I had ten lives, you know? Because I would do this for one life, and then in another, I would try to be a brain surgeon or a marine biologist. You can see a pattern there, in science, right? I like to tinker and discover things. Especially, brain surgery, that’s the one I wish could do. But I love my job. I only have one life, unfortunately! So, space it is!

What advice would you offer someone who wants a career like yours?

You know, it’s tough, I have a lot of different feelings about this because I think that while our country needs a lot more people in STEM, I also think that there actually aren’t that many jobs in STEM. There are a lot of computer science jobs, which is great, that’s fantastic, but I think if you want a job in STEM that isn’t in computer science, you’re gonna have to push a little harder after school. The job isn’t just going to be sitting there waiting for you when you get out. You have to do the internships, that’s my number one recommendation for anybody who’s asking “how do I work at NASA,” is you have to do the internships. And if you can do an internship at NASA, so much the better; it doesn’t have to be at NASA, but if you do an internship at NASA — and it is not as difficult to get those as people might think — then you can come here and prove yourself. And all you have to do is work hard, do your job, and people will notice, you’ll be surprised.

What do you do for fun?

I have a baby now, she is about 10 months old, so free time has diminished a lot recently. But we still make time for fun, and she is part of the fun, of course. Before we had the baby, my husband and I, we liked to go to concerts. Probably the big thing we like to do is going to shows in the city. Lots of different stuff. Actually, you know, we’ve seen a whole bunch of crazy music, everything from Die Antwoord, which is this South African really kind of weird electronic music, to just indie stuff, or sometimes we’ve also seen very popular stuff like U2 and Muse. We just like to see live music. We have made time to continue that… I think we’ve seen 3 shows since she was born. Once she’s older, we’ll start bringing her along too, with the big headphones to protect her hearing!

Anything that you would like to share about your hobbies?

When I was in college I was in an A Cappella group, an all-women’s A Cappella group, so I’ve sung a lot. These days I don’t really take much time for that, unfortunately. I mean we go to karaoke, so there is always that. I love a good karaoke night — the cheesier the better. I can still sing alright. It’s not that impressive but I can carry a tune.

What accomplishment are you most proud of that’s not science related?

Besides my daughter, that’s the obvious one. It probably would be a singing thing, but that’s ages ago when I was in high school. I’m still really proud of this one choir I was in, in high school, it was called the All Eastern Choir; it was a combination all of these all-state choirs on the East Coast. A few people from each state got into this choir and it just managed to be terrific, and I just felt I was part of something really cool.

What’s your favorite space image?

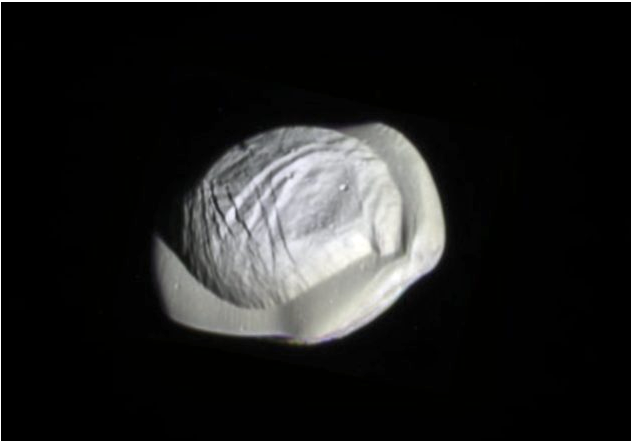

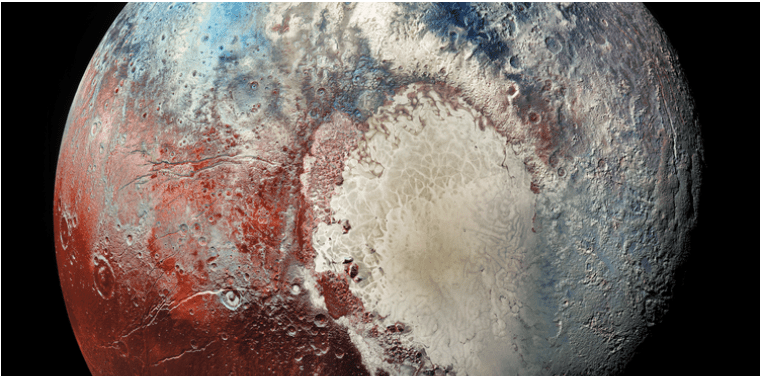

An image of one of the moons of Saturn, named Pan, a tiny little one that they found. They didn’t find it recently but they imaged it for the first time recently. It has this kind of flat pancake shape, and it was just amazing because it was essentially a rock that had accreted ice and dust grains only at its equator because its equator was constantly skimming grains from between the rings of Saturn. It was just such a beautiful image because it was, I don’t know, this tiny little block of ice and rocks way out in the solar system, and you can so clearly see physics happening on it. That shape is produced by stuff that I can easily explain with physics and plus it was so cute, this little thing is like a little pancake, it’s just adorable. That’s one of my favorite ones recently — you know I didn’t even study Saturn particularly. I love images of Pluto, too. I don’t study Pluto, but those are incredible as well.

Favorite quote: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” -Arthur C. Clark

Extra: I listen to NPR on my way to and from work, they do a ‘Perspective’. They do this local thing, where people can call in, and write a perspective and they get to read it, and they play it on the radio, and people write in about all sorts of stuff. And I’m always thinking, I should really write one, and read it, about space, and I can never quite think of what would be the most interesting topic, but something about how science is very human. I always wish that people could see that; that more people saw it that way. They are doing science all the time, they just don’t realize it. And more recently this vilification of science, or distrust of science, or associating it with elitism is strange to me because everybody does science. Anyway, I’d really like to send something like that in to the radio station.

Interview conducted by Fred Van Wert and Sara Rojo on August 20th, 2018.