NASA Is Sending E. coli to Space for Astronaut Health

Update from the EcAMSat team – December 1, 2017:

The EcAMSat mission has been a complete success to date. The experiment automatically started on Nov. 24, 2017, and concluded on Nov. 30, 2017. Throughout the experiment, EcAMSat’s systems have been stable and healthy, completing its investigation of antibiotic resistance without incident.

The satellite has completed all planned phases of the investigation, with portions of the data already downloaded. The EcAMSat team reports indications that both strains of bacteria have grown in space. A ground study on Earth is being run at NASA Ames with the same types of bacteria, to compare with the results from the satellite. With the complete data set and time for analysis, the science team will be able to draw a more conclusive understanding of the experiment’s results. Early results may be available as soon as a few weeks from today.

Ever wonder what would happen if you got sick in space? NASA has sent bacteria samples into low-Earth orbit to help find out.

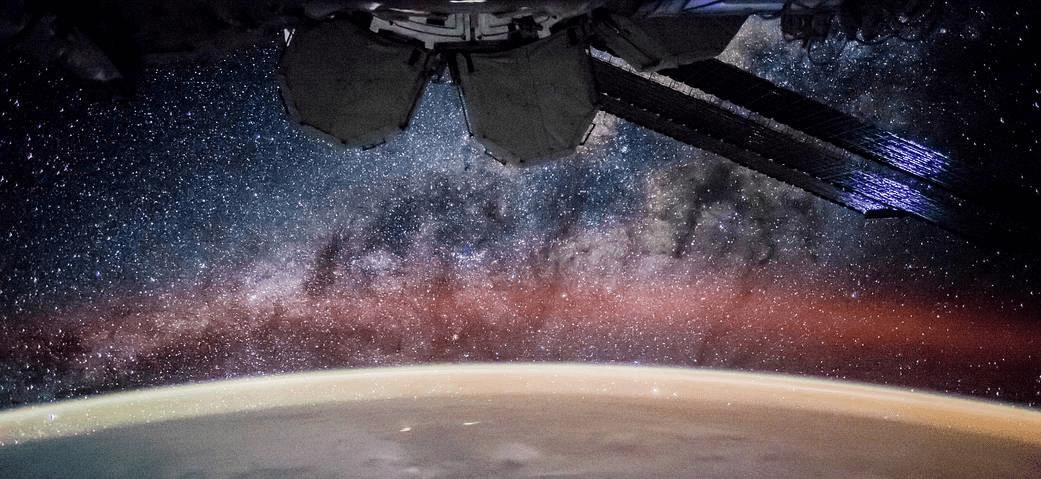

One of the agency’s latest small satellite experiments is the E. coli Anti-Microbial Satellite, or EcAMSat, which will explore the genetic basis for how effectively antibiotics can combat E. coli bacteria in the low gravity of space. This CubeSat – a spacecraft the size of a shoebox built from cube-shaped units – has just been deployed from the space station, and may help us improve how we fight infections, providing safer journeys for astronauts on future voyages, and offer benefits for medicine here on Earth.

“If we find resistance is higher in microgravity, we can do something, because we’ll know the gene responsible for it, and be able to design countermeasures,” said A. C. Matin, principal investigator for the EcAMSat investigation at Stanford University in California. “If we are serious about the exploration of space, we need to know how human vital systems are influenced by microgravity.”

Scientists believe that bacteria like E. coli may experience stress in microgravity. This stress triggers defense systems in the bacteria, making it harder for antibiotics to work against them. Bacteria on Earth do something similar by developing a natural resistance to traditional antibiotic treatments. By knowing how E. coli’s resistance to antibiotics changes in space, we can also better understand bacteria on Earth, leading to more effective treatments here, too.

The E. coli strains used on EcAMSat are responsible for urinary tract infections, which can happen to astronauts in space in addition to other types of infections. With these results, scientists will learn about the ideal dosage of medicine to combat E. coli infections in space and explore other techniques that could enhance the power of antibiotics that already exist today.

“Beyond low-Earth orbit, the compounding human health effects of microgravity and space radiation will require more knowledge about how biology reacts to the space environment,” said Stevan Spremo, project manager for the mission at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. “Lessons learned in this experiment will serve as a stepping stone for more advanced biological CubeSat missions, answering critical questions.”

EcAMSat is a uniquely autonomous satellite, meaning it can conduct its experiment without any communication from Earth. After arriving at the International Space Station, crew will work with ground controllers to release the satellite into orbit, and it is programed to automatically begin its experiment. Students at Santa Clara University in California will monitor the spacecraft, handle mission operations and download data.

The spacecraft will awaken the dormant E. coli by flooding them with a nutrient-rich fluid, adjusting their containers to the temperature of the human body, and then injecting the bacterial samples with different amounts of antibiotics. Two types of E. coli will be compared: one with a naturally occurring gene that helps it resist antibiotics, the other without.

The bacteria will be mixed with a dye that changes from blue to pink. A dye that remains blue indicates most cells have died in reaction to the antibiotic. The more cells that remain viable and active in spite of the medicine, the stronger shade of pink the dye becomes. An on-board color sensor will detect these changes and determine how strongly the two types of E. coli resist the antibiotic at different doses.

The experiment will last for 150 hours as EcAMSat orbits the Earth, and the dataset, less than a megabyte in total, will then be transmitted via radio down to Earth. After the conclusion of its mission, this little satellite will burn up in the Earth’s atmosphere some 18 months later.

Keeping Astronauts Healthy Today, Searching for Life Tomorrow

EcAMSat is not only building on a legacy of reliable hardware design demonstrated on prior small satellite missions, but also maturing technology for future missions to enhance our understanding of life in our solar system. In the future, some of the same components designed for EcAMSat could live on in other missions.

“Though EcAMSat will only fly this once, many of its components may embark on a different mission: life detection in the solar system,” said Tony Ricco, chief technologist for the mission at Ames. “Using sensors and the microfluidics technology from EcAMSat, NASA is developing the technology needed to look for life on moons such as Enceladus and Europa – ocean worlds covered by icy crusts.”

In a package the size of a couple loaves of bread, the science from this satellite will provide health benefits for future astronauts and humans on Earth for decades to come.

The EcAMSat mission is managed at NASA’s Ames Research Center, in collaboration with Stanford University, through the Space Biology Project Office, sponsored by the NASA Headquarters Space Life and Physical Sciences Research and Application Division in the agency’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate.

Author: Frank Tavares, NASA’s Ames Research Center

Media contacts: Darryl Waller, NASA’s Ames Research Center