Helicopters today are considered a loud, bumpy and inefficient mode for day-to-day domestic travel—best reserved for medical emergencies, traffic reporting and hovering over celebrity weddings.

But NASA research into rotor blades made with shape-changing materials could change that view.

Twenty years from now, large rotorcraft could be making short hops between cities such as New York and Washington, carrying as many as 100 passengers at a time in comfort and safety.

Routine transportation by rotorcraft could help ease air traffic congestion around the nation’s airports. But noise and vibration must be reduced significantly before the public can embrace the idea.

“Today’s limitations preclude us from having such an airplane,” said William Warmbrodt, chief of the Aeromechanics Branch at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California, “so NASA is reaching beyond today’s technology for the future.”

The solution could lie in rotor blades made with piezoelectric materials that flex when subjected to electrical fields, not unlike the way human muscles work when stimulated by a current of electricity sent from the brain.

Helicopter rotors rely on passive designs, such as the blade shape, to optimize the efficiency of the system. In contrast, an airplane’s wing has evolved to include flaps, slats and even the ability to change its shape in flight.

NASA researchers and others are attempting to incorporate the same characteristics and capabilities in a helicopter blade.

SMART rotor technology holds the promise of substantially improving the performance of the rotor and allowing it to fly much farther using the same amount of fuel, while also enabling much quieter operations.

William Warmbrodt

Aeromechanics Branch

NASA and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, also known as DARPA, the U.S. Army, and The Boeing Company have spent the past decade experimenting with smart material actuated rotor, or SMART, technology, which includes the piezoelectric materials.

“SMART rotor technology holds the promise of substantially improving the performance of the rotor and allowing it to fly much farther using the same amount of fuel, while also enabling much quieter operations,” Warmbrodt said.

There is more than just promise that SMART Rotor technology can reduce noise significantly. There’s proof.

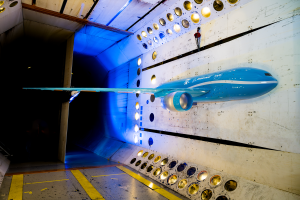

The only full-scale SMART Rotor ever constructed in the United States was run through a series of wind tunnel tests between February and April 2008 in the National Full-Scale Aerodynamics Complex at Ames. The SMART Rotor partners joined with the U.S. Air Force, which operates the tunnel, to complete the demonstration.

A SMART Rotor using piezoelectric actuators to drive the trailing edge flaps was tested in the 40- by 80-foot tunnel in 155-knot wind to simulate conditions the rotor design would experience in high-speed forward flight. The rotor also was tested at cruise speed conditions of 124 knots to determine which of three trailing edge flap patterns produced the least vibration and noise. One descent condition also was tested.

Results showed that the SMART Rotor can reduce by half the amount of noise it puts out within the controlled environment of the wind tunnel. The ultimate test of SMART rotor noise reduction capability would come from flight tests on a real helicopter, where the effects of noise that reproduces through the atmosphere and around terrain could be evaluated as well.

The test data also will help future researchers use computers to simulate how differently-shaped SMART Rotors would behave in flight under various conditions of altitude and speed.

For now that remains tough to do.

“Today’s supercomputers are unable to accurately model the unsteady physics of helicopter rotors and their interaction with the air,” Warmbrodt said. “But we’re working on it.”