To mark Aviation Maintenance Technician Day this Sunday, May 24, NASA’s James “J.C.” Coleman, III plans to work with his son on changing the transmission of their 1990 Nissan 300ZX at their home in California’s Antelope Valley.

The plan couldn’t be more perfect.

Since 2008, this is the day each year everyone in the United States is asked to take a moment and give thanks to the more-than-quarter-million men and women who keep airplanes in the air by working on them on the ground.

The date was chosen because that’s the birthday of Charles Edward Taylor, the man credited with building the engine the Wright Brothers used to make their first historic flights in 1903.

So, if you’re looking for an aviation maintenance technician – AMT for short – to appreciate, Coleman is certainly a worthy candidate. He’ll be the one with tools in hand and dirty fingernails.

For more than two dozen years as an AMT Coleman has inspected, repaired, upgraded, and otherwise maintained some of the nation’s most sophisticated aircraft for the Air Force and NASA.

Today he is a division chief at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in California, overseeing a team of some 300 people responsible for keeping 33 research and support aircraft in flightworthy condition.

It’s a charge he and his colleagues take seriously, even to the point of demonstrating a haughty boast they come to honestly and has been shared by many proud AMTs throughout the history of flight.

“It may be the pilot who gets all the glory, but it’s the AMTs on the ground that should get all the credit,” Coleman said. “We’re responsible for that airplane, from nose to tail. If it flies well, or if it flies poorly, that’s a reflection on its ground crew.”

Put another way, it’s the AMTs who own the airplanes, while pilots just borrow them for a bit and hope to bring them back in the same condition or risk the – good-natured? – wrath of the ground crew.

It’s not arrogance. It reflects the respect and seriousness to which AMTs approach their work because it can literally mean the difference between life and death.

“That really is a mentality that is bred into the culture of AMTs. That aircraft on the ground is ours. If the pilot has a successful mission, it is in no small part due to the maintainer,” Coleman said.

A Familiar Story

If there is such a thing as a stereotypical AMT, it’s probably someone who tends to work on their own cars, has a tool for every job, and loves to create and build things, Coleman said.

So, it’s probably no surprise Coleman’s personal tale echoes the origin story of many AMTs working today.

Originally from Raleigh, North Carolina, Coleman was bit by the bug at an early age. Not so much an aviation bug – although he had an interest in airplanes – but more of a mechanical one.

“Even as a kid I would take apart my toys to see how they worked and try to improve them as I put them back together,” Coleman said.

To save money, his father would do all the maintenance on the family car and young Coleman would help, providing the practical training that gave him confidence in knowing he was indeed mechanically inclined. (He wouldn’t buy his first new car until 2017.)

His interest in figuring out how things worked initially prompted pursuit of an electrical engineering degree. He began his studies at North Carolina State and continued at North Carolina A&T until money ran out.

His father insisted that if Coleman wanted to finish school, he had to pay his own way. The Air Force turned out to be the solution, even if it meant an unsure future as a certified AMT instead of holding an engineering degree.

“I had no idea what an aircraft maintainer was when I joined the Air Force, or even really how an aircraft flew other than you put a whole lot of power behind it and hopefully it takes off,” Coleman said.

During the next 24 years Coleman would ascend through the enlisted ranks to the top, retiring in 2019 as a Chief Master Sergeant stationed at Edwards Air Force Base in California. He and his wife of 21 years, Carmen, also raised a son, Jalen.

Along the way he would work on many different types of aircraft – trainers, fighter jets, spy planes – and earn two degrees: a Bachelor of Science in Aeronautics Technology and a Master of Science in Aerospace Operations Management, both from Embry Riddle Aeronautical University.

A is for Aeronautics

When Coleman retired from the Air Force in 2019, he didn’t travel far for his next job at NASA, as he only moved a couple of miles down the edge of massive Rogers Dry Lakebed from Edwards to Armstrong.

In starting his civilian career at the nation’s space agency, Coleman said some his Air Force colleagues wondered what he would be doing “up there” and needed to be reminded that the first A in NASA stood for Aeronautics.

“We do fly aircraft and we do it exceptionally well!” Coleman said he told his friends.

Armstrong’s aircraft fleet includes 33 airplanes, of which there are 12 different major types. These range from the big DC-8 airliner-turned-research-platform, to small electric-powered drones.

“The beauty of working at NASA is the variety of aircraft we fly,” Coleman said.

Armstrong’s fleet also includes F/A-18 and F-15 fighter jets long since retired from the military. The F-15 was the first type of airplane Coleman worked on in the Air Force and it remains his favorite today.

But it’s also a kind of love-hate relationship as the F-15 represents for Coleman and his team the kind of challenge they face in maintaining aging aircraft NASA inherited from the military and industry.

“The older and more high performance they are, the more love and attention they need,” Coleman said. “They are beautiful when they fly but when they break it gets increasingly more challenging and expensive to find spare parts or to make our own.”

The hunt for spare parts might require Coleman’s team to look through old, grounded aircraft stored at Armstrong or Edwards; travel to other desert airfields where large numbers of retired aircraft are sent; or seek out help from NASA’s other research centers with aircraft operations.

“We really have excellent relationships with the Air Force here at Edwards and elsewhere, as well as with the other NASA centers. If you’re in aircraft maintenance you’re part of a kind of club and we all try to help each other out,” Coleman said.

AMT Work Ahead

At the same time the Armstrong team is working to keep their current aircraft flying, they also have an eye to the future.

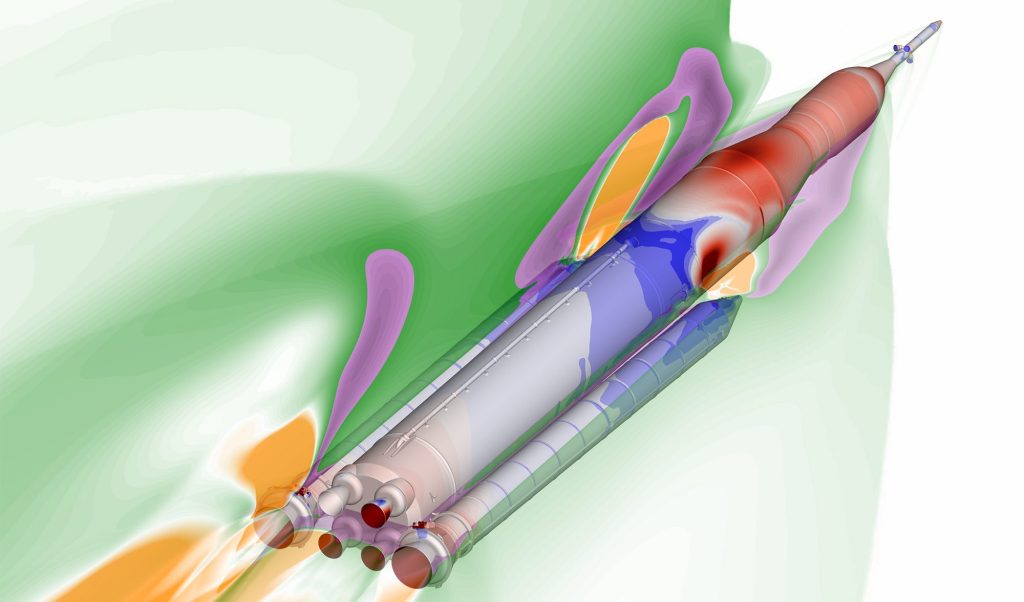

“We just took delivery of the all-electric X-57 and we’re working with our program managers to prepare for the supersonic X-59 – those are just two examples – so we’re definitely keeping busy and continuing to train and learn new things,” Coleman said.

The future also is bright for anyone thinking about joining the AMT ranks.

“Being an aircraft maintainer is one of the most rewarding careers. It is a labor of love. It is a skill set that will be needed because air travel in one form or another – and NASA is working on a lot of different ideas – is not going to disappear,” Coleman said.

His advice for anyone thinking about such a career: If you have a passion for working with your hands and with tools, and if you have a knack for problem solving and troubleshooting, then you probably have what it takes to succeed as an AMT.

And just because Coleman wound up working on high-performance fighter jets, among other advanced aircraft, being certified as an AMT means you can work on everything from the smallest single-engine General Aviation airplane to the largest jumbo jet airliners.

“When it comes to the general theory of aircraft maintenance and aircraft engine operation, while the complexity level can increase, there’s not a lot variance between the different aircraft you might work on,” he said.

Being an AMT is a career that certainly has worked out well for the North Carolina native, one that can be celebrated on Aviation Maintenance Technician Day this weekend.

“I truly believe I’ve got the greatest job in the world.”