During the cold winter months many airline passengers know what happens when it’s icy. Not only can it be tough to get to the airport – planes can end up being delayed and/or face de-icing while on the ground.

But ice formation in engines while the plane is flying – in certain weather conditions – is also a concern year round. Researchers, including a group from NASA, are in Darwin, Australia during its summer months to study the issue. They are part of an international team working to improve aviation safety by analyzing high altitude ice crystals with the help of a specially equipped French jet.

Engineers and scientists from three NASA facilities are supporting the European Airbus-led High Altitude Ice Crystals (HAIC)/High Ice Water Content (HIWC) flight campaign in the “land down under” through March 2014. The primary goal of the campaign is to fly into weather that produces specific icing conditions so researchers can study the characteristics present.

NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland is supplying an isokinetic probe for the Darwin flights that was designed and built by Science Engineering Associates and National Research Council Canada, with funding from NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration, as well as instrument and meteorological ground support. The probe is mounted under the wing of a French Falcon 20 aircraft. It measures the total water content in clouds that have high concentrations of ice crystals in the vicinity of oceanic and continental thunderstorms.

NASA Glenn has a 70-year history of icing research. “The data captured during the HAIC/HIWC campaign will add to the ground-based icing research NASA has already conducted in Glenn’s Propulsion Systems Laboratory,” said Tom Ratvasky, the NASA Glenn project scientist supporting the campaign. “We have tested a full scale engine under high altitude ice crystal icing conditions in that lab.”

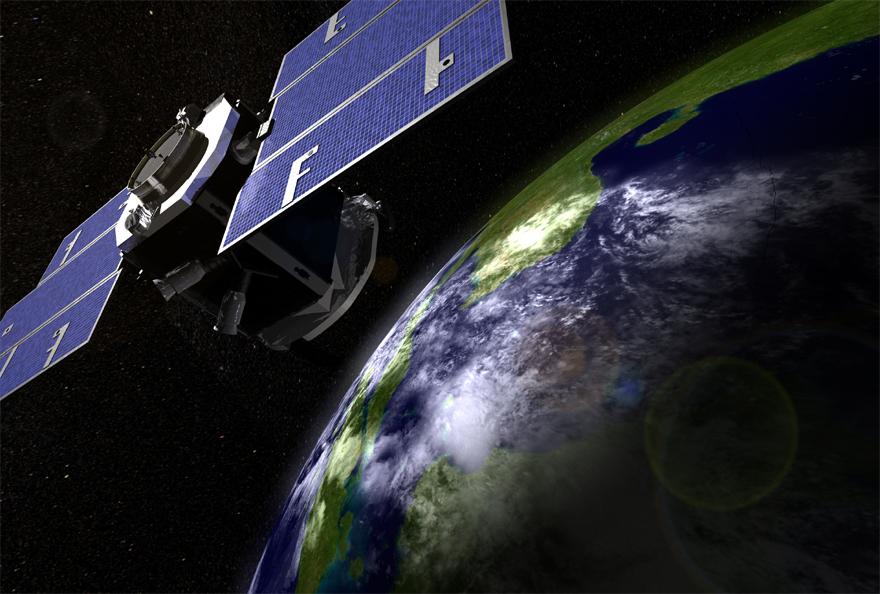

NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Va., and NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, are also part of the Australian research effort. The Langley researchers are contributing sensors expertise. One team is analyzing data from the Falcon’s onboard weather radar. Another is capturing satellite imagery to help forecast where the jet might encounter the best icing conditions. Goddard scientists are providing their cloud expertise, using flight data to improve modeling algorithms to predict the high ice concentrations in these environments.

“The aviation industry around the world is very interested in this research. That’s because ice crystals at high altitudes are not normally detected by onboard weather radar and visibly do not appear to be a danger to pilots,” said Steve Harrah, HAIC/HIWC weather radar principal investigator at NASA Langley.

“If those crystals are ingested into a turbofan engine and reach its core, they can cause a temporary loss of power – with no warning,” added Ratvasky.

Over the last 20 years, the aviation industry has documented more than 200 incidents where turbofan jet engines have lost power during high-altitude flights. For many of these events, the aircraft were flying in the vicinity of heavy storm clouds, but with little activity showing on the weather radar at their flight altitude. Investigators developed a theory that the planes are actually flying through clouds with high concentrations of small ice crystals.

The crystals are drawn into the engines where they melt on the warm surfaces inside. Surfaces eventually become cold enough during flight that ice can begin to build up, which can affect the engine’s normal operation. This kind of ice crystal icing may be occurring more often because more planes are flying and at higher altitudes with more efficient bypass engines.

“The research that will be compiled during the flight campaign will build on or redefine what we know about ice crystal icing at high altitudes,” said Ratvasky.”It will also help us better understand the physical processes that cause high concentrations of crystals in certain areas.”

What the researchers learn will also provide better information to the world’s aviation regulatory agencies. It should also help advance the development of technologies that may some day be able to detect the presence of ice crystals or lessen their effects in flight.