Safety of all systems and vehicles is a priority to protect human occupants participating in spaceflight missions. NASA heavily relies on the agency’s historical data and experience captured throughout the years to continuously make improvements to spaceflight operations, vehicle requirements, and medical guidance. Mishaps are also vital to document as they serve as lessons learned and play an important role in ensuring the safety of all crewmembers. Contingency planning utilizes a combination of the knowledge of a spaceflight system’s capabilities, mission goals, and historical experience to plan for potential off-nominal situations where the protection of human life is the sole focus.

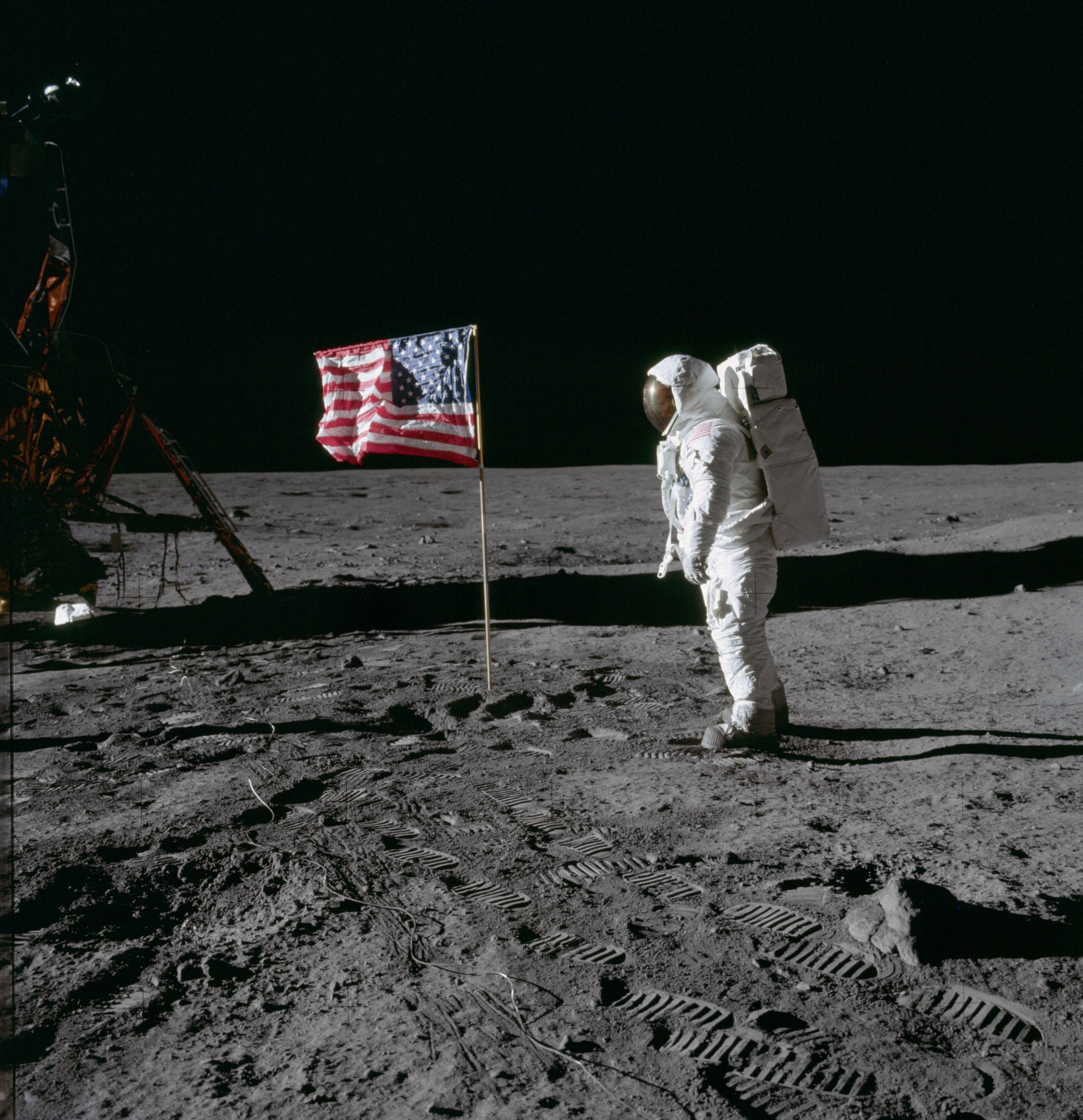

Apollo Lunar Lander

As NASA plans to return to the moon during the Artemis missions, important lessons can be drawn from the Apollo missions of the ‘60s and ‘70s. The Apollo Lunar Module (LM) successfully supported lunar descent, landing, EVA operations, all necessary crew functions for the duration of the mission and ascent from the surface. Using it as a starting point for reference can save time and resources for new designs, as well as provide the opportunity to address past issues.

Behavioral Health Mishaps

Spaceflight mishaps related to behavioral health problems have been quite low however, the actual incidence may be underestimated due to the reluctance of astronauts to report them. Behavioral health decrements can lead to performance-related effects that compromise the crew’s ability to function, especially under abnormal or emergency conditions. Some reported spaceflight incidents indicate that sleep loss, circadian desynchronization, fatigue, and work overload, as experienced by ground and flight crews, may lead to performance errors, potentially compromising mission objectives. Managing behavioral health conditions during space missions is critical for the mental efficiency and safety of the crew and, ultimately, for the mission’s success.

Crew Survivability

As future spaceflight missions become increasingly complex, longer in duration, and a further distance from Earth, readily available rescue and evacuation options must be evaluated to protect crewmembers during off-nominal survival scenarios. This technical brief explores options to support rescue scenarios by reducing the human usage of consumables (i.e., oxygen, food, water, power) to extend the mission to enable rescue. By considering these potential survival scenarios during the planning and design phase, providers can make informed decisions on vehicle capabilities, mission supplies, crew make-up and rescue options.

Decompression and LEA Suit Mishaps

During the Soyuz 11 mission in 1971 and the STS-107 Columbia mission in 2003, both crews were subjected to violent decompressions which resulted in their deaths. Each incident was caused by different factors, but in both cases the crew would have survived the

decompression event if they had been properly wearing their Launch, Entry, & Abort (LEA) suits. The Soyuz 11 crew were not wearing LEA suits at all, and the Columbia crew were likely not wearing their gloves or had their helmet visors lifted. NASA-STD-3001 outlines technical requirements with regards to LEA suits. The suits must be easily accessible by the crew, available for quick donning/doffing,

and able to accommodate any activity the crew is required to perform.

Entry Landing Mishaps

Re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, descent, and subsequent landing are a few of the stages in spaceflight that are life-threatening due to the myriad of processes and vehicle reliabilities that must occur in order for the crew to land safely and unharmed. The crew and vehicle are subjected to the vacuum of space, extreme heat, high speeds, g-forces, and vibrations. Historically, astronauts have sustained minor injuries, but loss of life has occurred, as well as near-misses. It is imperative that these lessons learned be considered in vehicle design and protecting the crew within.

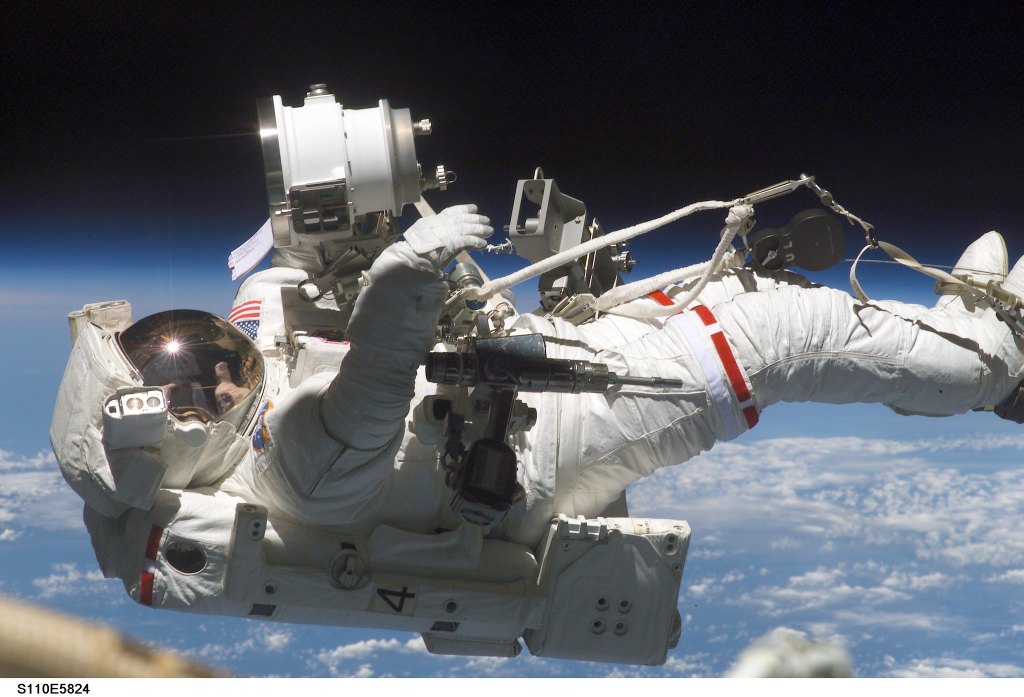

EVA Mishaps

Over the course of an extravehicular activity (EVA), the crew, equipment, and mission are all exposed to extraordinary risks. Tools can be damaged or lost, mission objectives can fail, and astronauts can suffer a wide range of injuries, from minor cuts and bruises to thermal burns. The astronauts’ lives depend on a long list of hardware and procedures operating as intended; if anything goes wrong the crew might not survive. EVA mishaps typically fall under three categories (or some combination thereof): hardware failures—where a tool or system does not perform its intended task, hardware damage, or missteps taken by the crew/mission control. Special considerations must be taken so that all the equipment used by the crew can withstand the rigors of the EVA tasks, and that the operations required of the crew do not put them at unnecessary increased risk.

Fire Protection

Throughout the history of spaceflight, there have been numerous combustion events that have ranged in severity. Besides injury due to

fire itself, a secondary hazard of fires is the inhalation of toxic combustion products. During and after a fire event, combustion products can present an immediate threat to the life of the crew due to the limited escape options, the fragility of the atmosphere, and the crew’s immediate need for safe air. The major approach to fire protection in current human-crew spacecraft is through prevention. Thus, fire safety relies strongly on the selection of materials proven to be fire-resistant through analysis and testing. During the design of new spacecrafts, trade studies for fire detection, fire suppression, crew response, crew protection, and post-fire clean-up and monitoring systems must be conducted. Improvements in the current fire-safety technology are necessary for future human-crew missions beyond low-Earth orbit. Deep Space exploration will challenge the existing tools and concepts of spacecraft fire safety.

Mortality Related to Human Spaceflight

Despite screening, health care measures, and safety precautions, crewmember fatalities are possible during spaceflight. Programs must establish comprehensive plans that make the appropriate decisions in terms of protecting the crew and mission objectives, determining the cause of death, and handling of the remains with dignity, honor, and respect while working with the crew’s families, other federal agencies, and international partners, while respecting the spiritual, religious and cultural aspects of remains handling. A spaceflight-related fatality event may occur during any operational mission phase (pre-flight, inflight, or postflight).

More Technical and Medical Brief Collections

Fundamentals of Human Health

Astronauts traveling in space are faced with both common terrestrial and unique spaceflight-induced health risks. The primary focus of NASA medical operations is to prevent the occurrence of inflight medical events, but to be prepared to provide robust clinical management when they do occur. Inflight medical systems face several challenges, including limited stowage capabilities, potential disruptions in ground communication, exposure to space radiation, and limitation of some functional capabilities in a microgravity environment.

Medical Operations and Clinical Care

NASA emphasizes the importance of comprehensive astronaut health. Considerations for the protection of astronaut health spans a continuum across a mission, including requirements for selecting a healthy crew, preparing the crew for a mission, and continuing to monitor and rehabilitate the crew postflight.

Vehicle Systems, Interfaces, Structure & Environmental Design

Spaceflight vehicles designed for human habitability must follow design considerations that accommodate the daily functions of the astronauts living onboard, including dining, sleep, hygiene and waste management, and other activities to ensure an efficient and healthy environment.