How do astronauts exercise on the International Space Station? How do they train underwater? Tara Ruttley, associate chief scientist for microgravity research at NASA Headquarters, has worked on a lot of fascinating projects to support the human spaceflight program. She also holds a Ph.D. in neuroscience and discusses how NASA studies the brain health of astronauts.

Jim Green:Our astronauts in space need all kinds of help. They need to be healthy. They need to work experiments. We need people on the ground to interact with them to make a mission happen.

Tara Ruttley:Being a part of real-life space program and really helping an astronaut get something accomplished like that was a real joy.

Jim Green:Hi, I’m Jim Green. And this is a new season of Gravity Assist. We’re going to explore the inside workings of NASA in making these fabulous missions happen.

Jim Green:I’m here with Dr. Tara Ruttley. And she is the associate chief scientist for microgravity research at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. But prior to that, she was the associate program Scientist for the International Space Station, working at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Welcome, Tara, to Gravity Assist.

Tara Ruttley:Thanks for the invitation to be here. It’s super cool to finally be on this really great podcast.

Jim Green:You know, I would say your background’s really unique since you started out, as I understand an engineer, and then became a scientist. How did that happen?

Tara Ruttley:Well, I never wanted to be an engineer, quite honestly. But I have always wanted to work for NASA.

Tara Ruttley:And it was, in particular, in high school where I took a trip to the Johnson Space Center. And it was a field trip, and I got to meet an astronaut. And I said, what does it take to be an astronaut? He said, Just do what you love. Because the chances are, it’s really tough to get into the astronaut office. And, and you don’t want to spend your entire life doing something you don’t love. So do what you love. We want to hire successful and happy people in the astronaut office.

Tara Ruttley:And that’s what I did I that’s why I pursued science. But while I was working on my undergraduate degree in biology, I ended up having to work with a lot of mechanical engineering students, because I had these great ideas for designs for exercise equipment for use in space. And I needed someone to help me implement them, and and come up with ideas and concepts. And so I got to know the mechanical engineering students at Colorado State University where I was going to school. And not only did they help me implement my concept, I learned how to use the machine shop, how to help do design, I learned a lot about mechanical engineering.

Tara Ruttley:And I got accepted to the mechanical engineering master’s degree at Colorado State University. And when I was just about to graduate out of that, that is when I applied to work for NASA, my dream job. And NASA said, well, we’re in a hiring freeze, we can’t hire right now. But give us your resume anyway. So I gave them my resume. And they called me a few days later. And as luck would have it, they were creating a new division in the engineering directorate called Biomedical Systems Division. And they wanted me to come work on exercise equipment and medical hardware for the International Space Station. And I say it was luck. But what it really was, was being prepared for the big opportunity. So that opportunity came I was I was fully prepared, and I ended up going to work as an engineer at NASA. That’s where I worked for the first eight years, and it was everything I could have wished for. I could not have made that that career up. That was the perfect fit for me.

Jim Green:Well, you also got your PhD in neuroscience. So what does neuroscience has to do with space exploration?

Tara Ruttley:So while I was an engineer, I went ahead and pursued my PhD in neuroscience as well. And you know, I thought about this question, Jim, a lot.

Tara Ruttley:Space exploration, neuroscience. They’re both exploratory type sciences, right? You’re you’re trying to solve a lot of the problems of the universe, the questions, the big questions in the universe, I think with both of those, and I think I’m just naturally drawn to them. I mean, think about it. I think I’ve read that. In terms of what we can see in the universe, we can we humans only see like 5% of what’s really out there.

Tara Ruttley:And the brain is the same way. There’s so much more out there about our own brain inside of our heads, we don’t even know. And so both of these could keep scientists busy forever and ever trying to trying to solve all the problems in answer all the questions. And so I really think and I never meant to put those two things together, I just really think that I think that’s the type of curious thinker I am. And maybe I’m trying to search for, you know, the philosophical answers to who we are where we came from. Maybe that’s what drove me.

Jim Green:Absolutely, I understand completely. Well, you know, you started then at Johnson Space Center. And as I understand it, it was all about developing an exercise bike for Space Station users.

Tara Ruttley:Yeah.

Jim Green:All right, for those astronauts. What’s the bike all about? And why was that important?

Tara Ruttley: So the bike is one of three, what we call exercise countermeasures that we have on the International Space Station. So on station for the last 20 years, we’ve had anywhere from three to six people who stay on the station for up to six months. We’ve also had up to a year. And the reason we do this is to find scientific discoveries, right? First, we want our humans up there so that we can understand the changes in their bodies so that we can prepare them to stay longer, and go beyond low Earth orbit to places like the Moon and Mars. So we study their their changes the body changes in space.

Tara Ruttley:But we also do things like try to understand why plants are having a hard time growing or how fluid behaves or how we put out fires in space. So this big orbiting laboratory up there now needs people to run it. So those people need to stay healthy. So to do that, the bike is one of three. So we have the bike, we have a treadmill, and we have a resistive exercise device. The bike, the purpose of the bike, is to maintain a heart-healthy situation. We want to keep the heart the cardiovascular system healthy for the astronauts. Because the heart is a muscle. And if you don’t use it, you lose it. And on earth, we use it every day as we climb stairs and walk and run and move.

Tara Ruttley:But in space, you don’t use your muscles so much. You don’t move as much against gravity. So your heart could be at risk of getting smaller, and what we call atrophy. So we have to keep that that heart pumping like a muscle. The treadmill is also for cardiovascular and it’s good for heel strike.

Tara Ruttley:So when your foot hits the ground, it actually imparts a force to the bones, and the bones stay healthy that way too. And then the resistive exercise device is based on the vacuum of space, if that’s the resistive component, because you can imagine if there were regular weights, they would just float away.

Tara Ruttley:Now the bike was cool, because yes, that was the first thing I worked on as an engineer. And it’s just like the bike you would ride on Earth, except for a few things. First of all, think about when you’re biking, you’re, you’re moving a lot, you’re vibrating a lot, you’re causing a force, they hit the ground with your bike. So this exercise device, this bike, which is located in the US lab, is actually on these springs, so to speak, or these wires, that, that cause that remove the vibrations from the bike to the station, because if that that bike was hard mounted to station and you were pedaling away, the whole station would start vibrating. And so it’s it’s basically detached and kind of floating around as you bike it dampening the vibrations.

Tara Ruttley:Secondly, it doesn’t have, the bike doesn’t have a seat, you don’t need a seat. And if you’ve ever ridden the bike for a long period of time, you’re probably glad about that. But it doesn’t have a seat bottom. Because you’re floating, you don’t really have a place to need to put a seat bottom, but it does have a back. So you strap yourself down to the bike, you’ve got a back support, and you’re just pedaling away, you’ve got the shoes that will clip in just like on earth, and then you just dial up the watts to what your exercise prescription is for the day.

Jim Green:Well, you know, Space Station is a wonderful place to do all kinds of research in an environment we call microgravity. What is microgravity?

Tara Ruttley: Yeah, microgravity is not that you’re simply floating, it is that you’re falling out at the same rate of the earth right. So you’re freefall you’re in freefall around the planet, it’s it’s a nice balance of, of the physics.

Tara Ruttley: And now you can study behaviors of systems in a way that you can’t study on Earth. Because we are all we are everything you see all the behaviors you see the way that we are designed, we’re all because of that huge gravity vector, the biggest force that we encounter, so when you take that away, things like sedimentation, or particles settling to the to the bottom of a glass in fluid, that goes away. You don’t have sedimentation in microgravity. You don’t have buoyancy or the mixing of things in microgravity. You don’t have bubbles that are floating to the surface and you don’t have very good heat transfer or convection either.

Tara Ruttley: Every science experiment you’ve ever done on Earth, think about how that might be if that gravity vector of that dominant force was removed, what might the outcome be. And so that’s what’s really cool about getting to be involved in the science on the space station, we have a lot of scientists who’ve been the first ones to see a whole lot of really new discoveries. And so that’s what makes it exciting working in this field, too, is nothing is what you’d expect it at all all the time.

Jim Green:So what’s your favorite story about working with the astronauts on space station?

Tara Ruttley: So when I was a new engineer, I also worked on something called a temporary sleep station, which was test for short. And really, it was so early in the space station program that they didn’t have any sleeping quarters, they would just kind of, you know, not they would nothing private. So they would just kind of attach themselves to the wall like they did for shuttle. So we were busy working on a compartment that was the size of those of a standard rack in Space Station, that could actually give them a door and some privacy for a laptop, and also provide a little bit of extra radiation while they sleep.

Tara Ruttley:Because while they sleep, they close their eyes, they could see bright sparks of light hit their eyelids while they’re sleeping, it’s just a little bit of radiation coming through. So what was really fun was helping to design certain components that I got a little bit in on the design, but I was really fortunate to sit in on Mission Control when it was being installed. And so it was an overnight install, we were all tired. It was like the middle of the night or 2 am. It took several hours. But at the end of it all, and just sitting on console and being there real-time as a young early engineer, and getting all that feedback and that rush of being a part of real-life space program and really helping an astronaut get something accomplished like that was a real joy. You know, since then there are a lot of great science advancements and things that I’ve been involved in on Space Station. But for me, that one just sticks out the most.

Jim Green:So how hard was it for these astronauts in zero G to fit these beds in the space station?

Tara Ruttley:Yeah, it wasn’t as easy as you would think. Because the temporary sleep station is like building a room, So a space station has these big long racks that are a little bit taller than humans. So the the crew members had to first outfit the surrounding the rack with this cloth liner that we created, then they had the stuff in some plastic blocks to fit that we designed to hopefully fit just right to to be that that radiation protection, they had to install the doors. And then they had to outfit it.

Tara Ruttley:It’s not the same as just taking a sleeping bag and strapping it to the wall. This was your building the room that you’re going to sleep in. And so now once they did that, though, they had access to being able to watch movies in their own in their own little rooms, change in their rooms call down and talk to people at home or their have conversations with their flight surgeons in that room. And so psychologically, and I would imagine physiologically, it was just it was just so needed that that that that sleep station on orbit.

Jim Green: Cool, that sounds great. Well, back here on Earth, you also were involved in a NASA program called NEEMO.

Tara Ruttley:Yeah.

Jim Green:And so what is NEEMO?

Tara Ruttley:So what this is, is it’s a it’s an underwater habitat called Aquarius. And it’s located off the coast of Florida, about 65 feet deep. And it’s actually run by NOAA. And it’s used around year round by marine biologists who want to stay in a in a environment under the ocean that they can just go out and scuba dive every day and study marine biology. And when you’re 65 feet down, but you’re breathing air pumped in from the surface, you become saturated you what we call saturated diving. So nitrogen starts to take over the place in your tissues where oxygen usually is, if you’re a diver, you know that you can only dive so deep for so long before you have to stop and slowly decompress and slowly come to the surface over time, so that you can get that nitrogen out and get the oxygen back in your tissues. And you can avoid the bends.

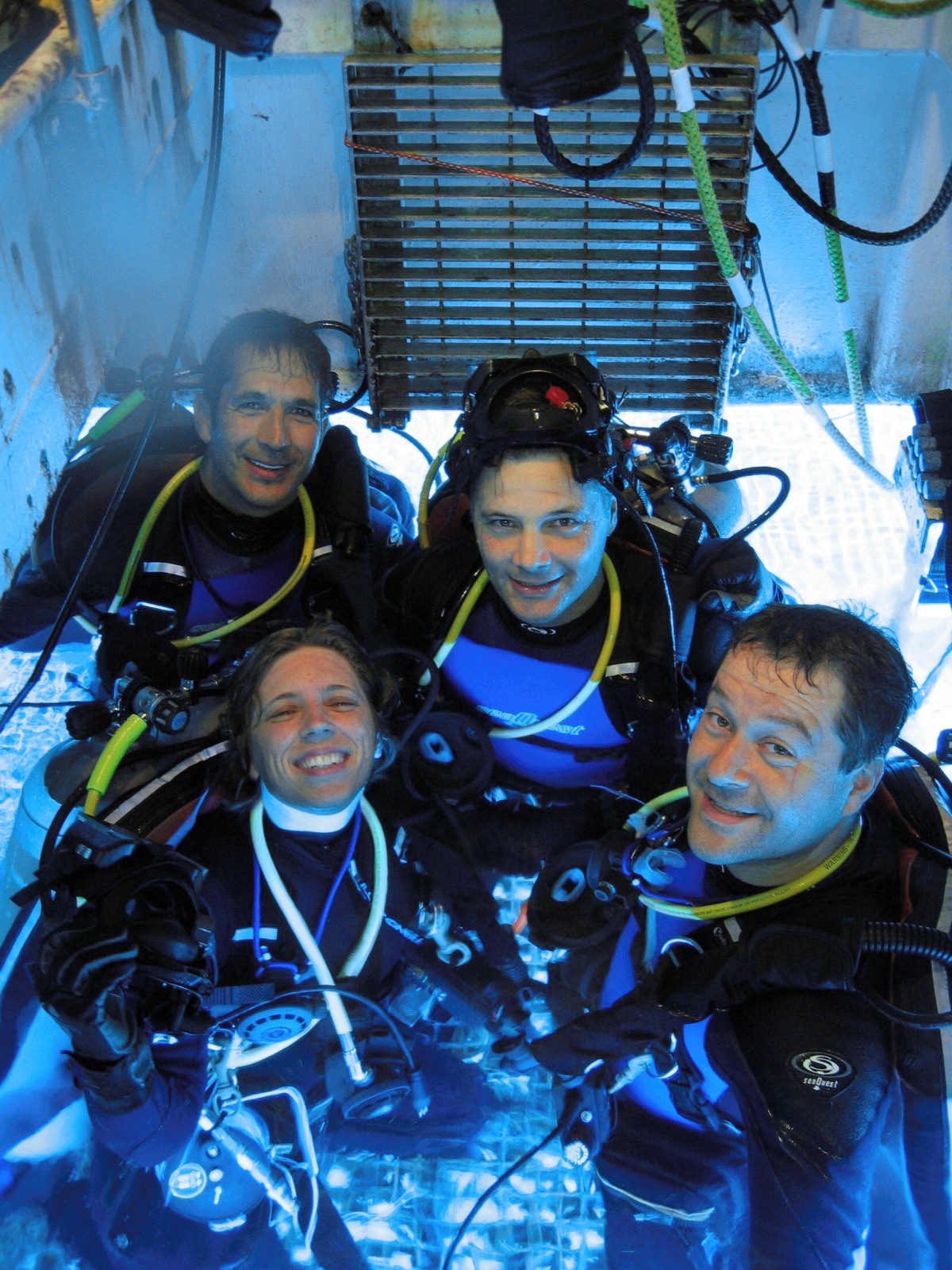

Tara Ruttley:So but when you’re going down into that habitat, you’re down there for 65 days, they’re there for two weeks at a time, they’re saturated. And so that’s what we so that’s what we call an extreme environment. That’s why NASA was interested in working with NOAA on using that environment for about two missions a year. So what that what we did was spend 10 days under the ocean in that habitat, doing lots of experiments, that that I helped coordinate and design that we might on hardware that we might want to use on the space station someday.

Tara Ruttley:So it was me and three other astronauts and two techs down there for 10 days doing simulated spacewalks. But we were also doing coral reef measurements, contributing to marine biology solutions, and testing hardware for what we might want to use on the space station.

Tara Ruttley:We were also doing a lot of communication activities like we had to, we had to work together as a team to build an underwater structure that was that was sort of frustrating, but was meant for you to, to learn how to be a good team. And the reason NASA chose that place is because you can’t easily just come to the surface if something happens. It’s like going to the moon or Mars. You can’t just come home right away if something an emergency happens. You can’t just swim to the surface. You’ll get the bends.

Tara Ruttley:So it’s NASA way of training the astronauts and testing out experiments and hardware in what we call an analog or simulated environment that would be as extreme as you might see or close that you possibly could get on Earth to what you might see on a on a lunar or Martian mission.

Jim Green: Now, how big is the habitat that’s sitting down at 65 feet? And how easy can you get around? And do you wear a scuba suit all the time, or?

Tara Ruttley:Okay, so the habitat itself, I forget the real dimensions of it, but it was about the size of a space station module. So it wasn’t that big. I mean, I think it had a bedroom. And then it had a dining area, which was also a lab and then it has something called a wet porch. So when you’re inside of it, no, you don’t wear the scuba suit. And you get to look out the window and see all the fish and maybe fellow scuba divers going by, but you’re inside nice and dry, and warm. And in our bedrooms, there were bunks and you could see out at night, you could see the fish go by which was really neat. And so we ate foods that you would eat in space, maybe there were freeze dried or camping type of food. And, and there was a shower facility and a bathroom. And there was that wet porch. So the wet porch was the area that you would don on your scuba gear and go down into the water.

Tara Ruttley:So that wet porch type piece was kind of like an inverted bell where the the air pressure was on the top and the water was on the bottom. So you literally put on your scuba gear, walk downstairs into the water and swam away. We did do scuba dives for up to eight hours a day. Even at that level you could become you could get something called nitrogen narcosis because you still have a lot of nitrogen in your tissues. And we went a little deeper when we did our scuba dives and stay longer. And so we were constantly monitoring each other for the sillies for the sillies because nitrogen narcosis can make people silly and confused and disoriented. So it was our job as buddies very safety conscious to monitor each other the whole time. We were actually scuba diving, once we got back into the environment, we were we were much better. And I will say it was funny in the environment because you’re at two and a half atmospheric pressure, our voices changed our vocal cords didn’t vibrate the way they do at one at one atmosphere. So I mean, I sounded the same, but the guys (laughs) sounded more like me. (laughs), And I got to tease them a lot for that.

Tara Ruttley:And then our astronaut crew lead, our chief was John Herrington. John said that two and a half atmospheric pressure felt like it was pressing on his sinuses. We constantly felt like we had a little bit of a puffy head kind of sinus issue. He said that felt a lot like what it was like to be in space.

Jim Green:Well, you know, I’m a diver, too. I haven’t done yeah, years. But I want to know, after you got saturated, what did it take to come out? You know, you had to go through a decompression stages. What was that like?

Tara Ruttley:What they do is they close the doors to the habitat. And, and they have you for the first, the first eight to 12 hours, I can’t quite remember, you lay flat on your bunk so that all of your joints are, are, you know, laid out flat, there’s no no bubbles gathering in your joints. And they start to slowly decrease the atmospheric pressure. So they start to start start to simulate you slowly coming up to the surface, they take it in increments over a 24 hour period. So the first 12 hours, you’re laying flat and your bunk so it’s overnight while you’re sleeping, or you’re watching TV or something. And then the second 12 hours, you you’re able to move around as you’re getting ready to pack up and go. And then when they get to the surface, right the surface, you’re still 65 feet deep, but the pressure is that of the surface, they open the doors, you have your gear on, and then you can just swim right out to the top. So you’ve done that decompression already.

Jim Green:Got it. Wow, that’s neat. I never thought I thought you’d have to get in your scuba gear and then hang onto a line at certain levels. But I’m glad you didn’t have to do that.

Tara Ruttley: It’s really neat. And I will say anybody who came to visit us had to hurry up and leave. So if we had any any goods brought down to us, or if we needed medical attention, or someone wanted to come take a picture or something, they had to go down and it’s 65 feet deep, so you can’t stay but maybe 10, 15 minutes, and then go back to the surface. So we had brief visitors, but not a whole lot.

Jim Green:So, Tara, relative to neuroscience activity, what’s happening on space station in that area?

Tara Ruttley:There are a few different areas actually are many different areas of of neuroscience activity happening on the station. One is that we have found over the last several years that our astronauts are coming back with vision problems, not all of them a good number of them enough for our human research program to be interested in. Why is this happening? Finally asking the question Why? Why is some of our crew members having eyesight problems in space, and it may be that it’s associated with the fluid shifts, as we are in space, the fluid a lot of the fluid shifts from our lower body up to our heads. And, and that fluid tends to put some pressure on the brain and as a result, the eyeballs and we think this might be something to do with what’s causing some of the vision problems that our astronauts are experiencing. Again, it’s not all of them, but it’s enough to for us to take a look.

Tara Ruttley:There are also other studies, investigating crew mental health and behavioral health. In fact, for a long time now, for the last 20 years or so on station, the crew has been keeping what’s called a journal and it’s it’s that it’s a research, it’s a research experiments and investigation of crew members writing in their journals about their feelings about their experiences, there are certain questions they can answer. And those things are under constant evaluation for ensuring the crew is mentally healthy and behaviorally sound. Right now we’re in low Earth orbit, where they stay maybe six months, and occasionally we’ve had one year, but now they’re going to get longer and further, further away from their planet. What does this mean for their behavioral health and, their motivation and things like that.

Jim Green:You know, Tara, I always like to ask my guests: What was that event or person, place or thing that got them so excited about being the scientist and engineer that they are today? I call that event a gravity assist. So Tara, what was your gravity assist?

Tara Ruttley:So when I was in high school, the movie Space Camp came out. That was probably 30 years ago now. And you know, as silly as it was, then it made me dream. And I thought, because there’s such a thing as space camp. So who would like I literally called the operator, zero, and I said, Can you connect me with space camp? And she’s like, yes, please hold.

Tara Ruttley:And I was like, there’s a thing called space camp? And, and for them, we did not have computers. So I couldn’t go to the website, right. So I got in touch with space camp. And they sent me the fliers the books for years, they sent me books every year about their new camp programs. And every year, we started saving money to be able to send me and when I finally went in high school, it’s where I met my tribe, people like me, who loved space as much as I did, because I didn’t know anybody who knew who loves space, I was really the outlier in my group, in my community. No one, no one was interested in that.

Tara Ruttley:So I met my tribe, I learned all the different ways that I could get into the space program. For a week, I was immersed in pretending to be part of the space program. And, and I was the one who picked, you know, the scientist position. I didn’t want the pilot, I didn’t want the commander, I wanted the scientist position, which was always easy. Everyone’s like, fine, take it. And so and then, and then I understood what I needed to do in terms of my career as well. I’d always known I had what I needed a PhD, I wanted a PhD. But attending Space Camp is honestly, what took my brain on a goal path, like from just from dreaming about it and thinking, yes, I want to I want to work for NASA one day, I want to be an astronaut one day, to getting there and getting the actual resources and getting immersed in that environment and to know that it’s a real thing that I can actually achieve. So I would have to say that space camp is my gravity assist.

Jim Green: Wow, that’s fantastic. Well, you know, you’re not the only one. I have heard this on several occasions. So the movie has sparked interest.

Tara Ruttley:Yeah.

Jim Green:Well, thanks so much for joining me in discussing your fascinating career working with astronauts and how you help them become healthier, and enable the work that they do on Space Station. Thanks so much.

Tara Ruttley: Thank you so much. This is such a fun interview. And I really appreciate being here. Thanks for the opportunity.

Jim Green: Well join me next time as we continue our journey to look under the hood at NASA and see how we do what we do. This is Jim Green, and this is your Gravity Assist.

Credits

Lead producer: Elizabeth Landau

Audio engineer: Manny Cooper