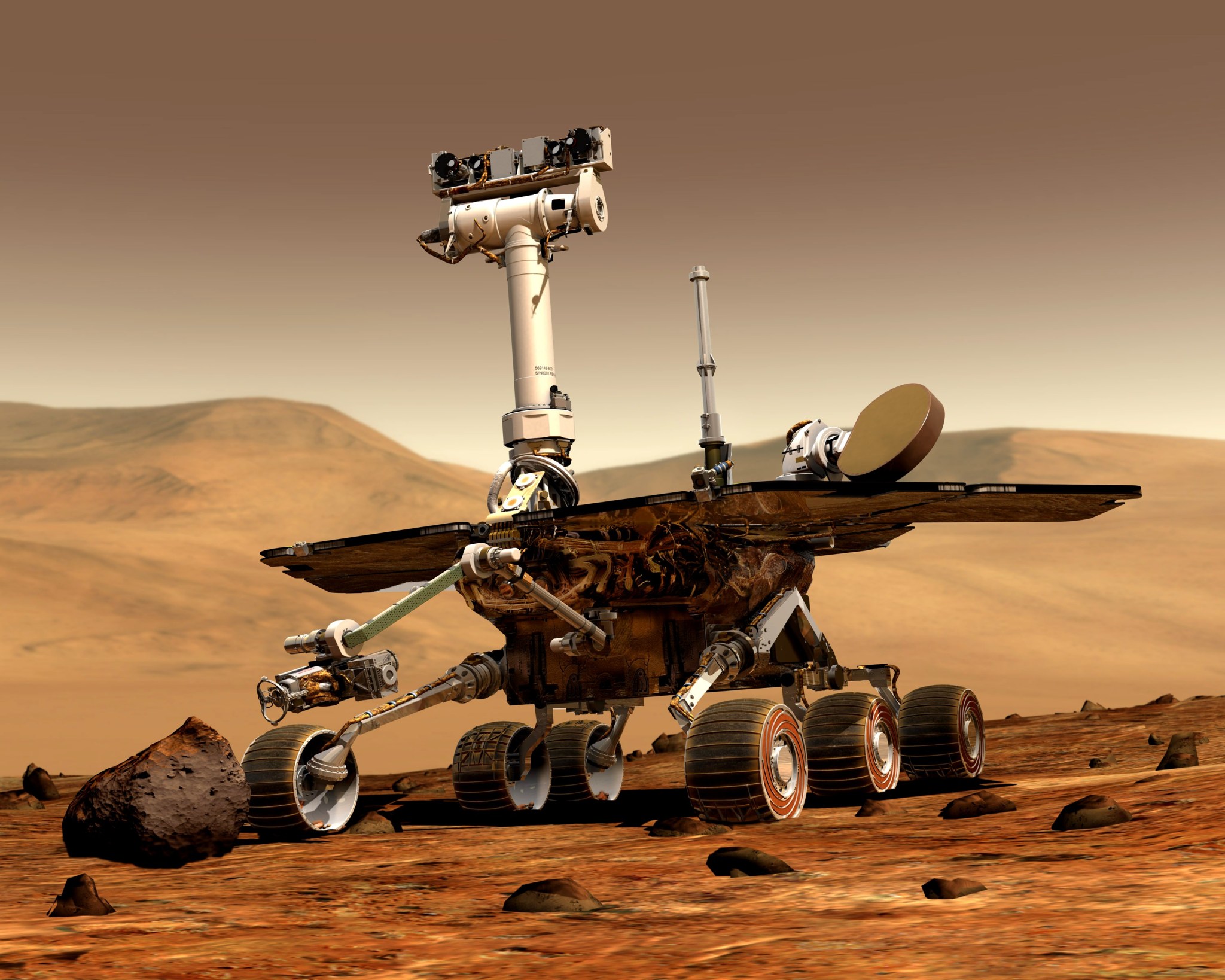

Androids rolling along distant planets were once only the stuff of science fiction. However, in recent years, mechanized trailblazers have become NASA’s precursors to human explorers. Among the most successful have been the twin Mars Exploration Rovers (MERs), known as Spirit and Opportunity, now marking a full decade of work on the Red Planet.

The Mars Exploration Rovers objectives were to search for and characterize a wide range of rocks and soils that hold clues to past water activity on Mars. Mission planners initially hoped the two rovers would operate for 90 Martian days, or sols. The term sol refers to the duration of a solar day on Mars, equal to 24 hours and 39 minutes on Earth.

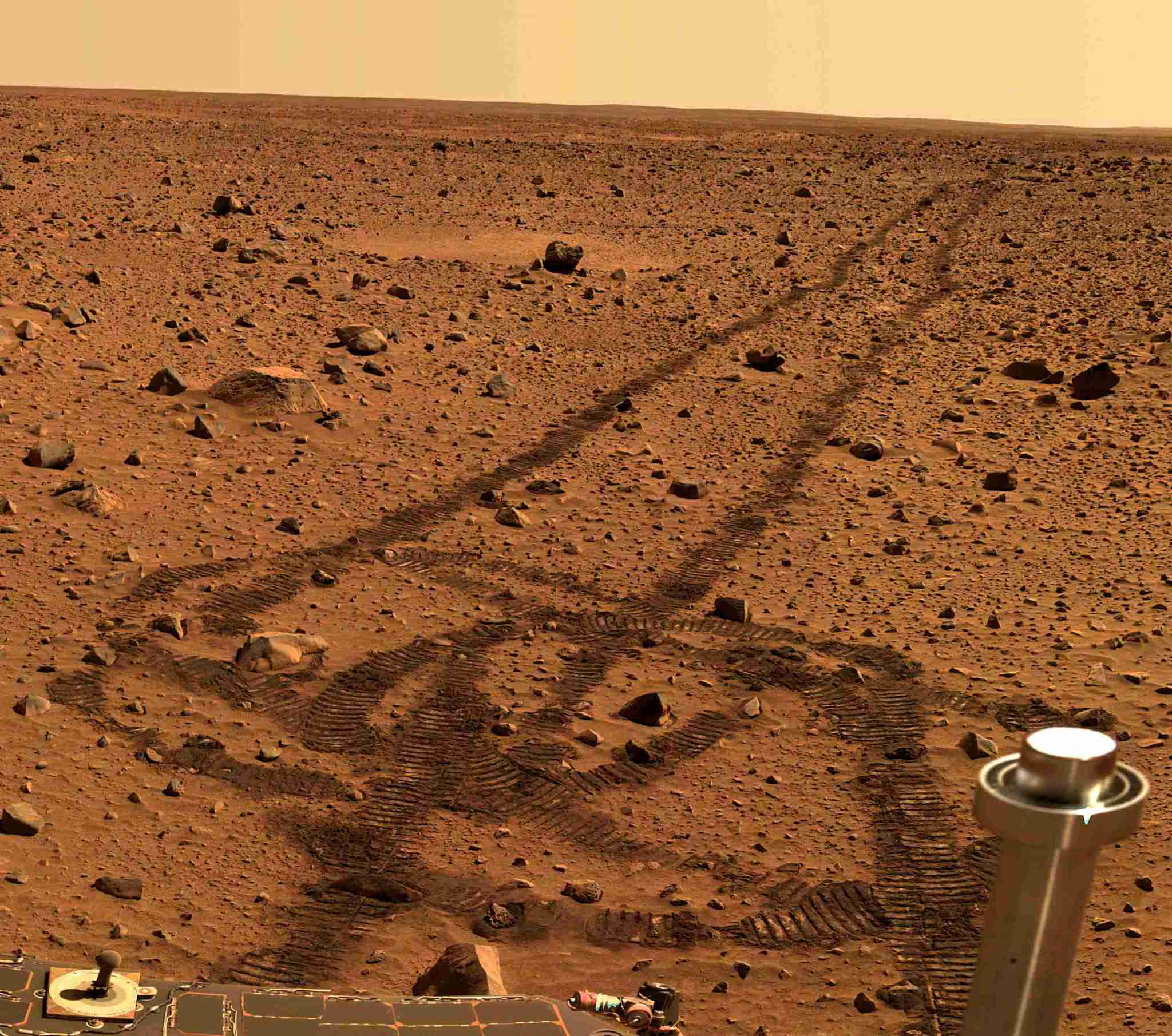

What followed went far beyond expectations. After 90 sols, both MER-A (Spirit) and MER-B (Opportunity) still had plenty of life, and multiple mission extensions kept Spirit functioning until March 22, 2010. Opportunity continues to operate, having traveled more than 24 miles across the Martian surface.

“The two rovers are a testament to NASA ingenuity and the confidence and investment the American people have placed in their space program,” said NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden remarking on the rovers’ longevity. “Together, these amazing robots will go down in history for their tenacity and their many findings.”

Preflight processing for MERs A and B began in early 2003 as the hardware began arriving at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Fla. Preparations included testing of the 410-pound spacecraft inside the spaceport’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility. The rover systems were given thorough checkouts for mobility and maneuverability. During this time, engineers and scientists at Kennedy worked closely with counterparts from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif., where the Mars Exploration Rover project was developed.

During April and May 2003, Delta II Heavy launch vehicles were stacked at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station’s Launch Complex Pads 17-A and 17-B. Spirit launched on June 10, 2003, and Opportunity followed on July 7, 2003.

Sheryl Bergstrom, manager of the JPL’s resident office at Kennedy, had high praise for the Kennedy launch team.

“Members of the spacecraft team are to be credited for their efforts,” she said.

Albert Sierra, of Kennedy’s Launch Services Program (LSP) Mission Management office, also complimented the joint effort.

“The team worked closely together nearly three years on the integration and launch activities for both missions,” he said.

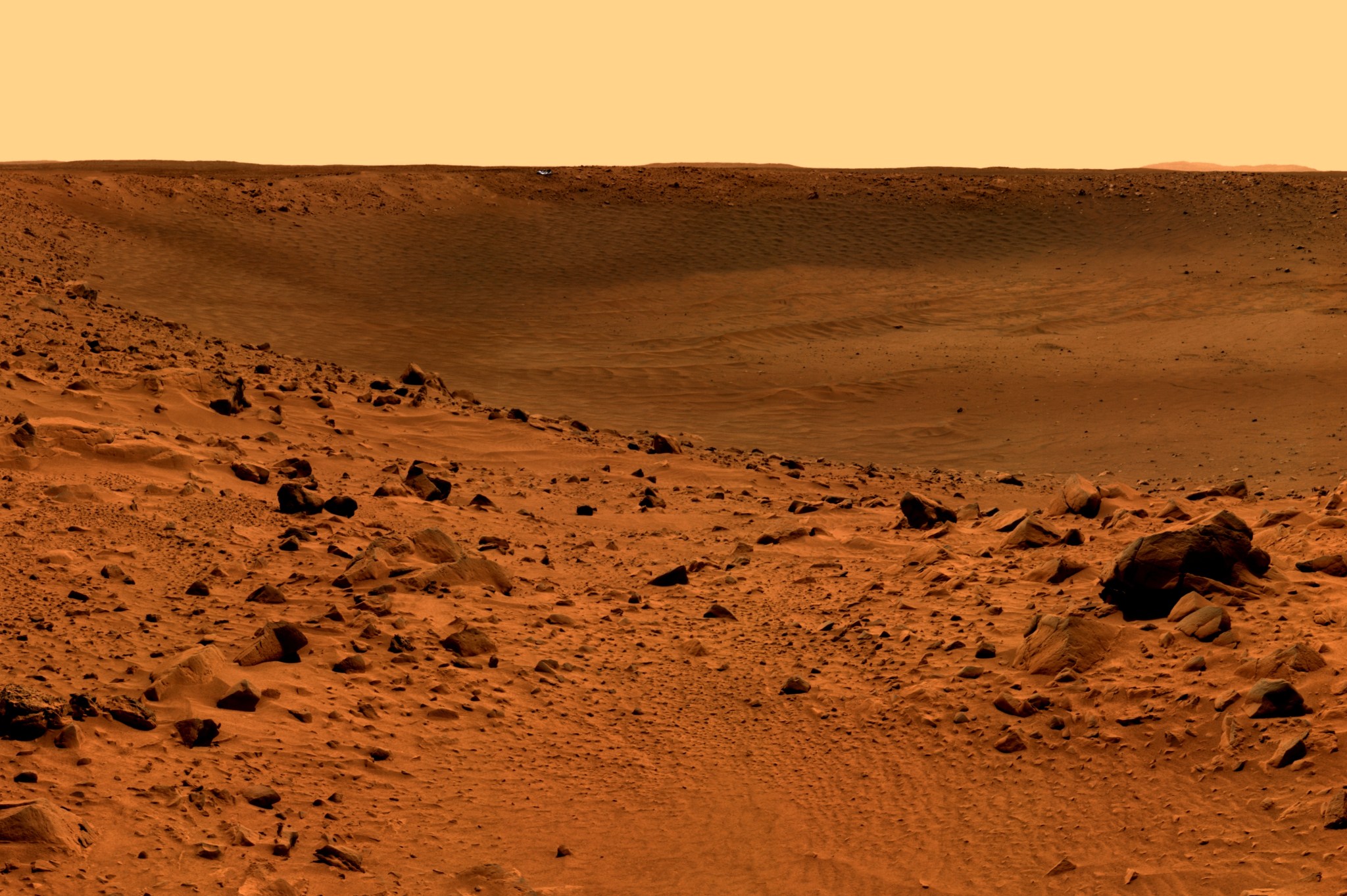

Following their seven-month trip to Mars, the rovers landed in widely separated equatorial locations on the Red Planet. Spirit successfully touched down on Jan. 3, 2004, at Gusev Crater, a Connecticut-size basin that appeared to have once held a lake. For Opportunity, NASA chose a location halfway around the planet from its counterpart. The second rover arrived three weeks later, on Jan. 24, in a broad plain named Meridiani Planum. The second site’s selection was based on a different type of evidence for a possibly watery past. Since experts consider water to be a requirement for living organisms, areas that once contained water are considered likely locations for evidence of past life forms.

“The instrumentation onboard these rovers, combined with their great mobility, will offer a totally new view of Mars, including a microscopic view inside rocks for the first time,” said Dr. Ed Weiler, then NASA’s associate administrator for Space Science.

Omar Baez, who was Kennedy’s Mars Missions launch director, now LSP launch director, put the landings in perspective.

“The hard geological science of reaching out and touching, drilling and analyzing the Martian surface is another stepping stone in exploring the universe,” he said.

It didn’t take long to make the first important discovery, with Opportunity hitting the jackpot early. It landed close to a thin outcrop of rocks. Within two months, its versatile science instruments found evidence in those rocks that a body of salty water deep enough to splash in once flowed gently over the area. Preliminary interpretations point to a past environment that could have been hospitable to life and also could have preserved fossil evidence of it.

Scientists evaluating data from Spirit later identified a water-signature mineral called goethite in bedrock, one of the mission’s surest indicators yet for a wet history on Spirit’s side of Mars. Goethite forms only in the presence of water, whether in liquid, ice or gaseous form.

“Goethite, like the jarosite that Opportunity found on the other side of Mars, is strong evidence for water activity,” said Dr. Goestar Klingelhoefer of the University of Mainz, Germany, lead scientist for the iron-mineral analyzer on each rover, the Moessbauer spectrometer.

In April 2004, the two mobile robots successfully completed their primary 90-sol missions on opposite sides of Mars and went into bonus overtime work. Spirit went on to function effectively over 20 times longer than NASA planners expected. After becoming stuck in the soft Martian soil, the rover continued in a stationary science platform role until communication with it stopped on March 22, 2010. Spirit logged 4.8 mile of driving instead of the planned 0.4 mile, allowing more extensive geological analysis of Martian rocks and planetary surface features.

As of Jan. 1, 2014, JPL’s Mars Exploration Rovers website reported that Opportunity had traveled just over 24 miles, surpassing the longest distance driven by a vehicle on another world. The record previously was held by Russia’s Lunokhod 2 rover that drove 23 miles on the moon in 1973.

The Opportunity rover continues to operate and is currently positioned on the edge of an exposed outcrop, a visible exposure of bedrock, where observations by orbiting spacecraft suggest the possible presence of small amounts of clay minerals.

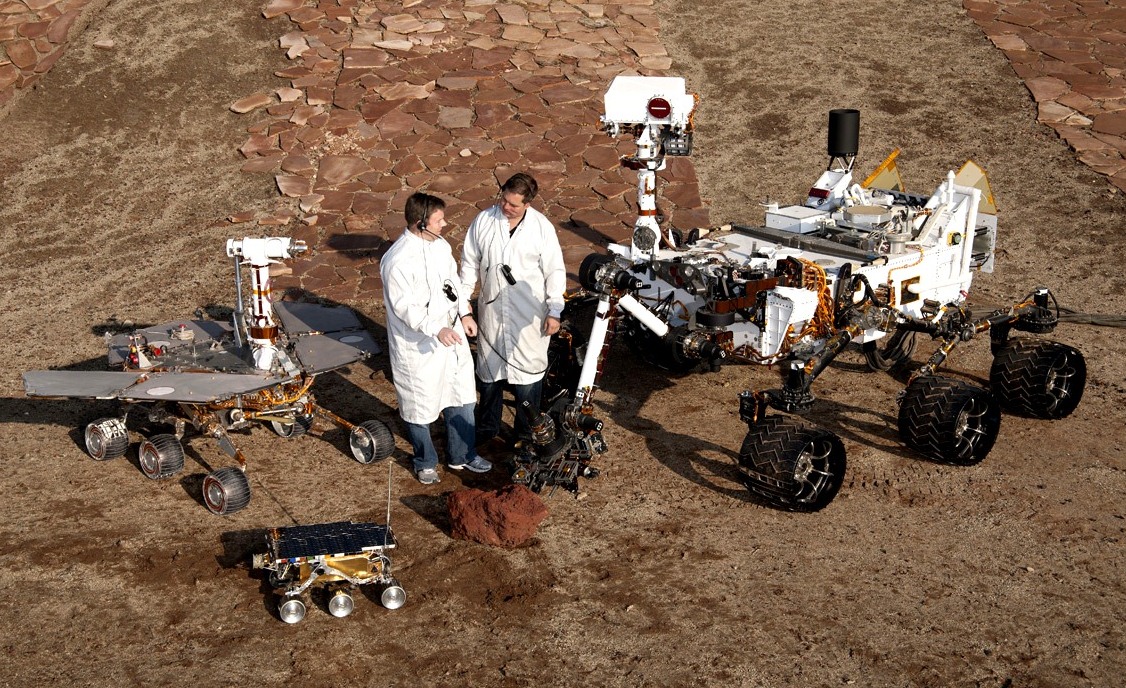

The missions of Spirit and Opportunity are part of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program, which includes three previous successful landers, the two Viking probes during 1976 and the Mars Pathfinder probe in 1997. The Mars Science Laboratory, known as Curiosity, joined its counterparts on the Red Planet on Aug. 6, 2012. In September 2014, NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN, or MAVEN, spacecraft is scheduled to begin orbiting the planet to study its upper atmosphere.

“All of this will pave the way for humans to travel to Mars in the 2030s,” Bolden said. “Science and exploration are working together to make this historic feat possible, and we’re developing technologies right now, including the Space Launch System and the Orion multipurpose crew vehicle, to take astronauts once again to deep space.”