Psyche Mission Co-investigator Ben Weiss discusses the mission to a unique metal asteroid orbiting the Sun between Mars and Jupiter.

Ben Weiss: Psyche is one of the largest asteroids in the asteroid belt. It’s about 72 miles in radius, 140 miles in diameter. So, there’s only a few hundred asteroids that are anywhere near that size. And it’s the largest, what we think to be metal-rich object in the solar system. That’s something we’ll be able to confirm once we get there. It’s certainly one of the densest known asteroids, and we think that it may be made out of a large fraction of its body out of metal. So, it’s really unlike any other world that a spacecraft has encountered before.

Deana Nunley (Host): That’s Ben Weiss. He’s a co-investigator on NASA’s Psyche mission, and our guest today on Small Steps, Giant Leaps, a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast where we tap into project experiences to share best practices, lessons learned and novel ideas.

I’m Deana Nunley.

Discovered in 1852 and named for the Greek goddess of the soul, Psyche is one of the most intriguing targets in the main asteroid belt.

It’s a pleasure to welcome Ben to the show to discuss the Psyche mission. Thanks for taking time to join us.

Weiss: Happy to be here.

Host: Could you give us a snapshot of your background and how you got involved with the Psyche mission?

Weiss: Yeah, so I’m a planetary scientist and I’m a professor at MIT. And there was another professor at MIT a few years ago named Lindy Elkins-Tanton, who had an office down the hall from me. And we used to talk about asteroids and their geologic history and their structures. And one day we were puzzling over some measurements I made in the laboratory of meteorites. In particular, I found that they were magnetized, that they contain records of an ancient magnetic field on their parent asteroid. And to make a long story short, we came up with this idea that some asteroids basically generated magnetic fields inside their interiors, that they formed little metallic cores like the Earth and that once had made magnetic fields, and wrote a paper about it. And that paper was read by some people at JPL, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. And then they asked us if we wanted to maybe design a mission to an asteroid to actually test these ideas. And that’s how my, and actually Lindy’s involvement in the Psyche mission got started.

Host: What is the Psyche mission?

Weiss: So, the Psyche mission is a spacecraft that’s being built by NASA, and it’s going to visit the asteroid named 16 Psyche. And 16 Psyche, we think, is the largest metallic or at least iron-rich object in the solar system. So it’s potentially our first opportunity to visit a metal world. A world not made out of rock or ice like which spacecraft visited before, but one made out of potentially metal. And there’s lots of really interesting questions about history and structure of asteroids, and how planets formed, and what the nature of planetary interiors is that we can learn from visiting this body.

Host: What are the science goals and objectives of the mission?

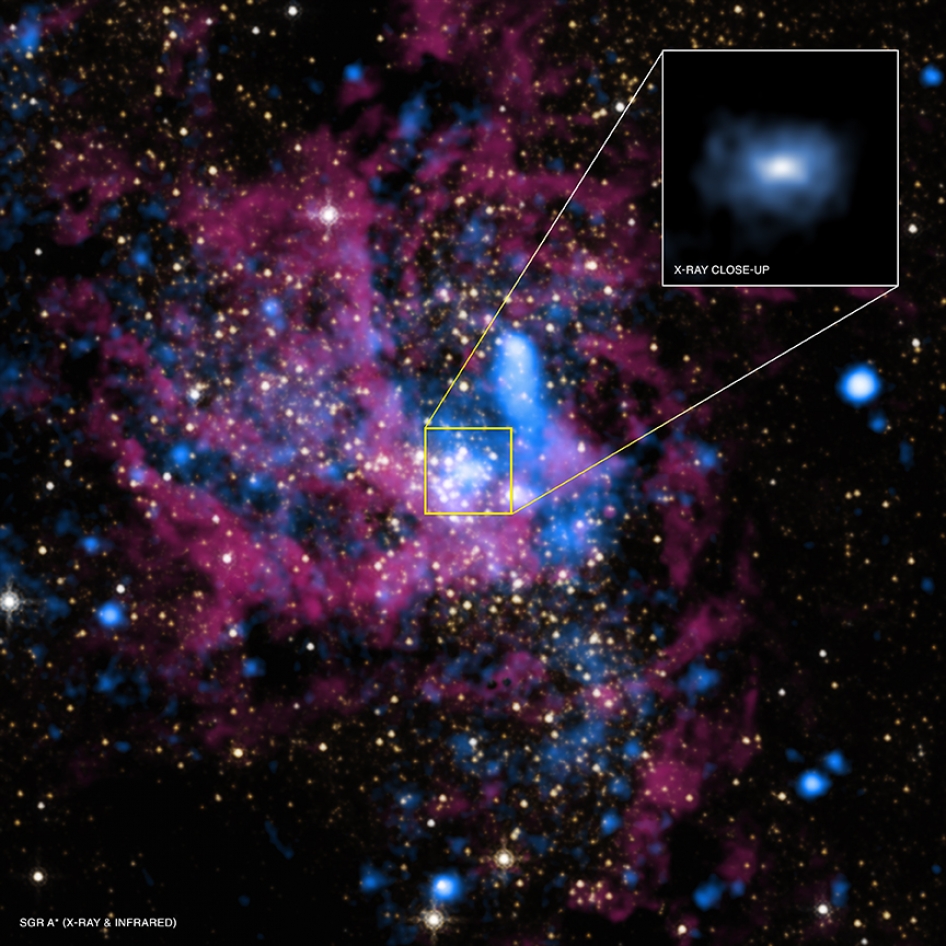

Weiss: So, the science goals of the Psyche mission, there’s three of them. The first one is to visit what we think is the core of a planet. We’ve never had a mission to the core of any planet. For example, the earth has a metallic core where we think its magnetic field is generated, but the temperature of the Earth’s core is hotter than that of the surface of the Sun. And the pressure down there is millions of times higher than what we have on the surface of the Earth. So, it’s inconceivable in my lifetime or many, many lifetimes that we’ll ever send a mission to the Earth’s core, despite what Jules Verne said. So, what’s so special about Psyche is we think, or at least we hypothesize, that it is the core of a body that had its outside stripped off early in the solar system probably by some impacts of other asteroids. Basically leaving bare this metallic core that we can go and visit today. So the first kind of mission to what we think is a metallic core is the first science goal.

Second thing is because Psyche is an asteroid, it’s basically a remnant of a group of bodies that formed in the early solar system, most of which are now gone. They basically were assembled to form the large planets we see today. So, Earth, Mercury, et cetera, was formed from these early asteroids, which we call planetesimals, or little planets. But there’s a very small fraction of these planetesimals that were never incorporated into a larger planet. And they now form the asteroid belt where Psyche resides today. And so by visiting Psyche, we can learn about the building blocks of the planets and learn about how planets formed.

And the third science goal is to basically visit a new kind of world made of a different material than we’ve ever visited before. So, we’ve sent many missions to rocky worlds. So, for example, we have the Perseverance Rover roving around on Mars. We’ve sent missions to Mercury, to Venus. We’ve sent missions to ice worlds. So, the Europa moving around Jupiter, Ganymede, these icy moons. Pluto, for example, icy on the surface. But we’ve never sent a spacecraft to a world that we think is made out of metal. So, just understanding what the geologic evolution of a metal world is, or even indeed what it looks like is a kind of major goal of the mission.

And it’s really interesting because we think that they’re actually, although there’s only one large, exposed metal body in the solar system today, which is Psyche. Psyche’s actually the biggest, what we think is the biggest metal object in solar system. We’re starting to see evidence for metal worlds, or at least iron-rich planets around other star systems. And so, it’s kind of an endmember for a class of objects that exist in the universe and that we can visit close up here in the solar system.

Host: So fascinating. We want to hear more about that as we go along. When is the mission scheduled to launch?

Weiss: It’s going to launch in August 2022. And then it’s got about a three-and-a-half-year cruise out to the asteroid belt, and then we’ll go in orbit around the asteroid Psyche at that point.

Host: And so, what’s happening now in preparation for launch?

Weiss: So, we are building the spacecraft and we entered what we call Phase D. So NASA missions are broken up into phases, phase A through F actually. And we’re in D, which is one of the most important parts of the construction process. We’re about to enter what we call ATLO, which is where they assemble the spacecraft in this big high bay at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where basically all the different components of the spacecraft, which had been being built all over the world, are going to be assembled onto the main spacecraft bus. And my specific role is to lead the magnetometer, which will be measuring the magnetic field of Psyche. That magnetometer is being built in Denmark at DTU, Danish Technological University. And this spring, we will integrate it onto the spacecraft at JPL.

Host: What are some of the instruments that will be used to explore the asteroid?

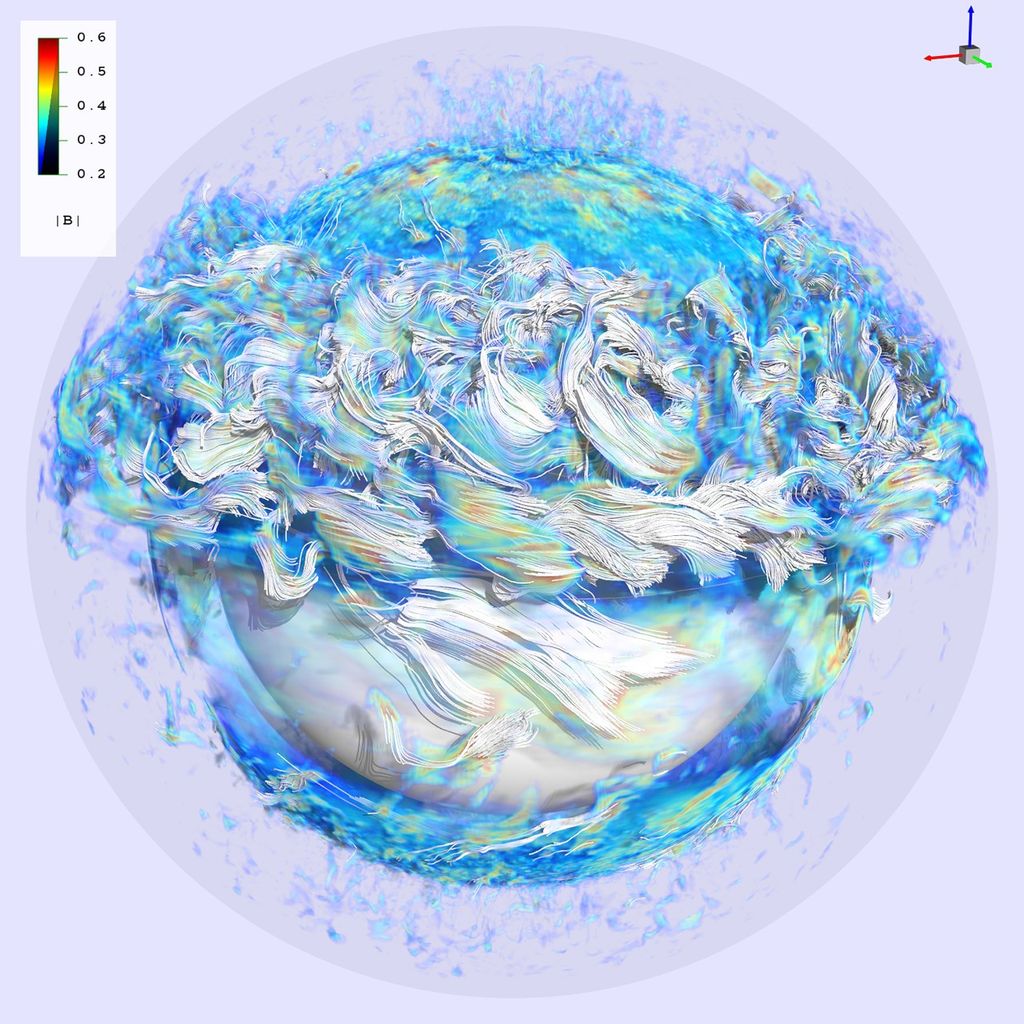

Weiss: The Psyche mission has three instruments. One, it’s got a camera, take pictures. Two, it’s got a magnetometer to measure its magnetic field. And three, it has an instrument called gamma ray and neutron spectrometer, which will measure the composition of Psyche. The magnetometer aims to measure Psyche’s magnetic field. Now Psyche is not generating magnetic field in its interior today the way the Earth is. So, the Earth generates a magnetic field in its core as the Earth’s core, which is liquid, churns during the process of cooling, like your lava lamp. And that leads to currents flowing in the Earth’s core, which then generate a magnetic field that we can see on the surface. So Psyche is certainly long been frozen if it ever was molten. And yet we think it might have a magnetic field frozen in to the metal out of which it’s made. And that frozen record of an ancient magnetic field in turn would produce a field that we could measure from the spacecraft.

So, the idea is to look for this fossil record of the ancient magnetic field recorded in the form of magnetization in these rocks that we could probe today with an orbiting spacecraft. So, if we see that Psyche is a strongly magnetic object, this would likely indicate that Psyche once generated its own magnetic field the way the Earth does today, which then basically produced this fossil record that we’re observing. Other hand, if Psyche is not magnetized, that may suggest that Psyche was never molten, and maybe it wasn’t even a core, but is some other kind of exotic iron-rich object. So, you see by measuring the magnetic field of Psyche, we can distinguish between the two leading hypotheses for how Psyche formed. One, that it was the core of a body that underwent large-scale melting and it had its outside stripped off. Or secondly, that it just happens to be a strange iron-rich object that formed without any kind of melting at all, but under gentle basically accretion or in-fall of cosmic dust.

The imagers will be telling us a lot about the topography and the composition and the geologic structures on the surface of the asteroid. And the first thing that we’re all going to be looking for with these images, is just to answer the basic question, what does a metal world look like? No human eyes have ever been laid on a body made out of metal. And just getting a picture of this thing and seeing what it looks like is going to be an incredibly exciting moment.

But as far as doing more detailed science, one of the major goals of the imager is to basically count the number of craters on the surface of Psyche, which will tell us how old it is. So the more craters there are, the older the surface is. We’d also like to know whether we can see evidence for volcanoes on the surface, as it has been suggested maybe when Psyche was a molten metal sphere, it cooled from the outside in so that the outside froze. And there’s an idea that maybe the mushy inside that erupted through kind of little metal or sulfide, iron sulfur volcanoes.

And then there’s the gamma ray and neutron spectrometer, which is going to measure the composition of Psyche. And a very basic question about the Earth and the other planets is what our planetary cores made out of? So, we think the Earth’s core is made out of mostly metal. But maybe there’s about 10 percent of the Earth’s core whose composition has been basically unknown despite being debated for decades. And what that extra 10 percent is, has major implications for lots of different things. For example, it may tell us why the Earth is able to generate a magnetic field and other planets can’t, depends on what the composition is. But unfortunately we have no samples of Earth’s core. We’re not going to be able to send a mission to the Earth’s core in our lifetime, for sure. And so the only opportunity we have to actually measure the composition of the core, other than looking at maybe iron meteorite hand samples, like iron meteorites that fall out of the sky, which we think might be samples of some asteroid core is to actually go and visit Psyche and measure its surface composition, using the gamma ray and neutron spectrometer.

Host: It’s going to be so neat to see these images and to learn more about the asteroid. How will the spacecraft communicate with Earth?

Weiss: The spacecraft is going to use a big antenna and basically communicate by radio waves. And that’s kind of a standard way that spacecraft communicate with the Earth. Now, Psyche also has an experiment on it, which is basically going to try out another form of communication using lasers, what we call optical communication, basically pointing a laser at the Earth and blinking it and modulating it so that you can send data basically through visible instead of a radio wavelength. If that works, it would potentially enable much, much, much higher data rates than what can be achieved by a spacecraft today. So that’s a technology demonstration. And if it works, it’s probably going to transform how space missions are done in the future.

Host: Really cool. Let’s talk about the propulsion system. How will the spacecraft travel to the asteroid?

Weiss: Yeah, so the spacecraft is going to be using this technology called ion engines, and in particular they’re called Hall thrusters. And they’re kind of like this science, fiction-y almost like Star Trek-y looking thing, which involves essentially using xenon, which is a noble gas like helium or argon and ionizing it. So stripping off some electrons so that it becomes charged. And then basically applying an electric field, such that you accelerate the ions.

So, it basically creates this kind of blue, glowing plasma that shoots out the back of the spacecraft at very high velocity, like tens of miles per second. And even though it’s a very fine tenuous plasma, because it’s moving so fast and also because we basically keep the ion engines on almost the entire mission until we get to the asteroid. So, for years. Over time, this leads to quite a bit of acceleration and the spacecraft can move quite fast. We also fly by Mars at one point. So we get basically a kick to the orbit from passing Mars. And that’s how we’re going to get to Psyche.

Host: Once the spacecraft slips into orbit around Psyche, what can we expect?

Weiss: So, when we get into orbit around Psyche, we’re going to first orbit relatively far away and basically measure the spacecraft’s gravity field from a distance. And then as we have a better and better understanding of its shape and gravity, we can slowly lower the spacecraft safely to closer and closer altitudes until eventually, we’ll be less than a few tens of miles above the surface. And as we get closer, we expect to be able to see the surface in sharper and sharper detail. We should be able to feel its gravity to really much, and much stronger and more precisely. And its magnetic field should grow as we get closer. So, it’ll be this slow kind of a gradual, spiraling in, parking in at four different altitudes and eventually getting very, very close to the surface to get high-resolution and high-sensitivity measurements.

Host: Would you say the Psyche team is facing unusual challenges?

Weiss: We’re definitely facing some unusual challenges as much of the rest of the world is right now. So we have the unique situation of building our spacecraft in the middle of the worst pandemic in a century, essentially. There’s been no period during the Space Age where society has shut down in any way at the scale that it has during development of the Psyche mission. And that has been an amazing and unique challenge that the engineers and scientists have met spectacularly. And I think we’re not going to miss our launch date. It looks like we’re on track to launching in August 2022, as we posed to NASA many years ago, despite this. And it’s a testament to just the careful, hard work and precautions that the engineers and scientists have taken to work safely and remotely whenever possible. So, we all haven’t seen each other in almost a year face to face. And we’re hoping that we can see each other for the launch in a year from this August.

Host: Oh, that’s just amazing to hear how that you’re continuing to keep this moving in spite of all these unusual circumstances. Really amazing. What are your thoughts on why people in general are so intrigued with the Psyche mission?

Weiss: I think people like Psyche mission, because the idea of going to a metal world is just plain cool. I mean, it’s like we have no idea what this place is going to look like. Is it going to be actually metal at all? We’re still not entirely sure if it is. We think it’s metallic. We won’t know until we get there. If it is made out of metal, what does a crater look like — an impact crater on metal — look like? Does it have the same shape, and bowl shape structure and lip around its edge? Is it circular? What do cliffs look like on a metal world? Is it all metal? Or could Psyche be made out of some more exotic materials like we see, for example, certain classes of meteorites are made out of metal and gem quality olivine peridots floating in it. We call those pallasites, and they’re some of the most spectacular geologic materials ever made.

We dream of the idea that Psyche has cliffs made out of these pallasites, with green crystals glittering in the Sun. And I think the thing that’s just so compelling about Psyche is that it’s unique and no human eyes have been laid on anything like it up until now.

Host: What do you see as the long-term benefits of the Psyche mission?

Weiss: The Psyche mission, I think its chief long-term benefit is that it just awakens our curiosity and kind of nurtures it. And it’s exploration for science and exploration’s sake. We’re not doing this for commercial reasons. Our major goal here is just to learn and explore about the universe.

Host: Many thanks to Ben Weiss for being our guest. You’ll find his bio along with a transcript of today’s episode on our website at APPEL.NASA.gov/podcast as well as links to related resources, including an APPEL Knowledge Services article about the Psyche mission.

For more interviews about what’s happening at NASA, check out other NASA podcasts at nasa.gov/podcasts.

If there’s a topic you’d like for us to feature in a future episode, please let us know on Twitter at NASA APPEL – that’s APP-el – and use the hashtag Small Steps, Giant Leaps.

As always, thanks for listening.