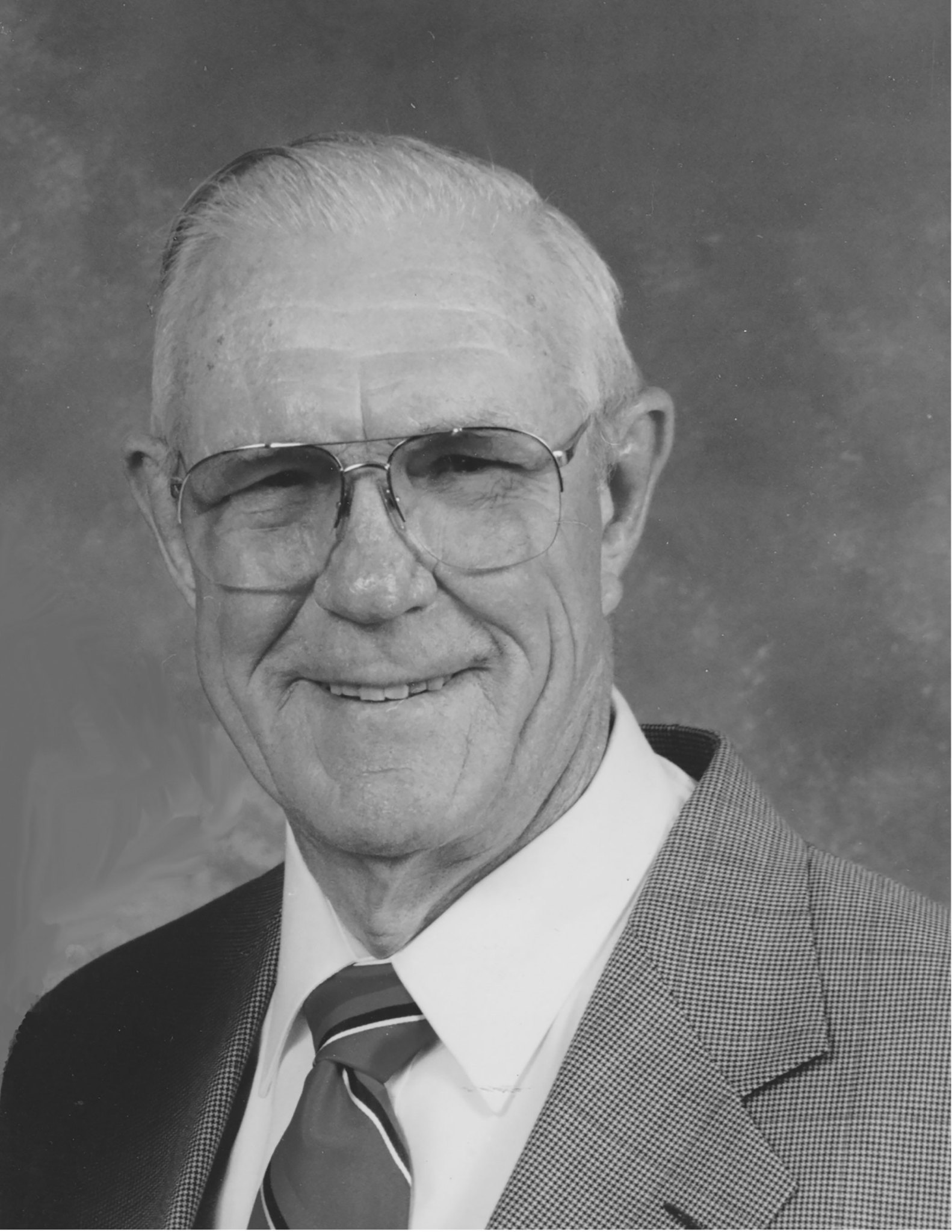

Robert A. Champine

Robert A. “Bob” Champine (1921–2003) was an outstanding research test pilot who made significant contributions to NASA’s aeronautics and space programs. He was a notable contributor to the understanding of phenomena that occur during transonic and supersonic flight. He logged over 11,300 flight hours in over 155 different aircraft.

Champine was born in St. Paul, Minnesota. As a young man, he became an expert model airplane designer, builder and competitor at contests for flying models. He developed an intense interest in becoming a pilot and aeronautical engineer. He attended the University of Minnesota and earned a bachelor of science degree in aeronautical engineering in 1943. While in college, he had begun primary flight training under the Naval Civilian Pilot Training Program and was commissioned an Ensign in the U. S. Navy. However, in order to become a Navy pilot he had to give up his commission and enroll in the Naval Cadet Program. After training in the program, he was commissioned as a naval aviator and subsequently flew many famous Navy fighters of World War II such as the Grumman F6F Hellcat, the Vought F4U Corsair, and the Grumman F8F Bearcat.

Near the completion of his Navy tour, Champine flew an F4U Corsair on an impromptu visit to the NACA flight hangar at Langley where he met with the head of test pilots, Mel Gough, and chief test pilot Herbert “Herb” Hoover, and was offered a job as a test pilot. He entered on NACA duty at Langley in December 1947. During this exciting period, he participated in many dramatic advances in aircraft technology and the space program.

Just a few months before Champine joined Langley, Captain Chuck Yeager had broken the sound barrier in one of the two X-1 research airplanes (Air Force’s X-1) at the NACA Muroc Flight Test Station in California. Two NACA test pilots, Herb Hoover of Langley and Howard Lilly of the NACA Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory at Cleveland, Ohio, were members of the test program for the second X-1 (NACA’s X-1). Unfortunately, Lilly was killed in May 1948 in a crash of the Navy’s Douglas D-558-1 Skystreak research airplane.

Champine accepted a request to replace Lilly, and arrived at the NACA’s Muroc Flight Test Unit in October 1948. After training from Hoover, he made his first X-1 flight on November 1 and became the sixth person and third civilian to break the sound barrier in the X-1. His next assignment was to conduct the first NACA research flights of another D-558-1 and the swept wing D-558-II Skyrocket. The latter program revealed unexpected deficiencies in the design, including a severe longitudinal instability (pitch up) that subjected Champine to 6-g’s during a maneuver.

In 1950, Champine returned to Langley because of lack of flying time at Muroc (then renamed the NACA High Speed Flight Research Station). Flight tests of the early X planes required considerable down time for modifications to the aircraft and detailed analysis of flight data– resulting in sparse opportunities for flights and considerable boredom for eager test pilots. In contrast to the situation at Muroc, Langley had about 40 to 50 aircraft in active flight research and extremely high levels of flight time for test pilots. Arrangements had been made with the Air Force and Navy to send the third airplane off the production line (later the fifth) of each new aircraft design to Langley for studies to improve its performance, stability, and handling qualities. Champine flew many of these airplanes to perform specified maneuvers and to discuss his evaluation with engineers.

With the advent of the jet age in the 1950s, Champine was assigned as project pilot for flight tests of the Navy’s new high-priority Vought F8U Crusader, which was exhibiting numerous challenges in its earliest versions, including fatal crashes. The problems uncovered by Langley flight tests included unacceptable g-force control behavior during maneuvers, which was determined to result from unintentional pivoting of the unique movable wing (variable incidence) used by the F8U. Working with Langley engineer Chris Kraft, the test team identified the structural source of the problem. The NACA warnings were heeded by Navy management, resulting in a temporary grounding of the F8U fleet. Champine and Kraft then encountered a Marine Major, a member of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics, who questioned the Langley results and doubted the conclusions drawn by the NACA–that Marine Major was John Glenn. However, following a detailed examination of the Langley results with Kraft and Champine, and interviews with Navy pilots who flew the aircraft, Glenn was convinced and became a believer. The F8U was subsequently redesigned, as recommended by Langley, and served the nation as an outstanding fighter during the Vietnam War.

The NACA made the decision to transfer all high-performance military aircraft research to its High-Speed Flight Station at Edwards Air Force Base in the 1950s, resulting in a major transition in Champine’s career as he refocused from flying supersonic military aircraft to evaluations of low-speed aircraft, experimental V/STOL vehicles, and rotorcraft.

During the late 1950s, Champine became a key contributor to the U. S. human spaceflight efforts.

In Project Mercury, he assisted engineer Max Faget in the highly successful design of the critical “g”-absorbing couch used in the Mercury capsules. He served as the first human model for the development of a mold technique used to form-fit couches for the original seven astronauts and many test pilots. He then participated in extensive evaluations of the Mercury couches in the Navy centrifuge facility at Johnsville, Pennsylvania, successfully experiencing accelerations of up to 18g’s and thereby validating the effectiveness of the couch concept.

Within Project Mercury, he assisted Charles Donlan in the selection of astronaut candidates for Project Mercury, and helped train the astronauts for NASA’s Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions at Langley using simulators that he helped develop. These included the Langley Rendezvous Docking Simulator in preparation for Project Gemini, and the Lunar Landing Research Facility to provide training for the Apollo missions.

While involved in NASA’s space-related research, he continued his aeronautical contributions. He was project pilot for pioneering helicopter research flights of the Langley Vertical Takeoff and Landing (VTOL) Approach and Landing Technology (VALT) program to develop and demonstrate automatic approach and landing using a modified CH-47 helicopter equipped with a variable-stability fly-by-wire control system. The successful demonstration of an automatic approach-to-landing capability defined the technology that could provide all-weather capability for future helicopters. Champine also served as project pilot for Langley flight evaluations of the XC-142 tilt-wing Vertical/Short Takeoff and Landing (V/STOL) transport.

He retired from NASA in January 1979, taking great pride in the fact that at no time during his 56-year flying career and his 32 years of flight testing had he ever been forced to bail out, despite some harrowing experiences with research aircraft.

Bob Champine was author or coauthor of over 50 technical reports and presentations, dealing with his extraordinary experiences in pioneering flight research for many of the nation’s famous aircraft, lessons learned in research projects, and his personal contributions to the selection and training of astronauts. He was well-known for his attention to detail and analytical precision.

His awards include induction into the Virginia Aviation Hall of Fame in 1979, the National Aeronautics Association Elder Statesman of Aviation Award in 2001, and a display on the Wall of Honor at the NASM Udvar-Hazy Museum in Washington, DC.

Champine died on December 17, 2003–the 100th Anniversary of Manned Flight–at the age of 82. He was survived by Gloria, his wife of 28 years, and five children: Jeffrey P. Champine, Richard E. Champine, Stephen C. Champine, Patricia D. Ditmore, and Terry C. Price.

Content of this biography is based primarily on Gloria Champine’s web-based salute to her husband’s life, entitled “He’s Got the Right Stuff” accessible at https://champine.wordpress.com/