If you’re fascinated by the idea of humans traveling through space and curious about how that all works, you’ve come to the right place.

“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center from Houston, Texas, home for NASA’s astronauts and Mission Control Center. Listen to the brightest minds of America’s space agency – astronauts, engineers, scientists and program leaders – discuss exciting topics in engineering, science and technology, sharing their personal stories and expertise on every aspect of human spaceflight. Learn more about how the work being done will help send humans forward to the Moon and on to Mars in the Artemis program.

On Episode 207, Sean Fuller, international partner manager of the Gateway program, shares how the successful model of international cooperation and commercial partnerships in the International Space Station program is being used to build an orbiting platform around the Moon. This episode was recorded on June 15, 2021.

Follow the Gateway on Twitter and Facebook for the latest news, milestones, and activities!

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 207, “Gateway to Partnerships.” I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight. Over the years, the International Space Station has orbited proudly as a beacon of international cooperation. Fifteen partner nations came together to build and operate an orbiting complex that’s hosted experiments and astronauts from even more nations. Its cooperative model has proven successful enough to lay the foundation for a new orbiting platform in space called the Gateway. Gateway, though, will find its place in orbit around the Moon as part of NASA’s Artemis program, to help establish a sustained human presence on and around the Moon this decade. And we’re not going alone. Building off the International Space Station program, we’re working with international partners and commercial industry to help achieve this goal. I got a chance to chat with Sean Fuller, international partner manager for the Gateway program, about how he’s pulling from his decades of experience in the International Space Station program to build this international orbiting platform around the Moon. We discussed the background and progress that support Gateway so far. So, let’s get right into it. Enjoy.

[ Music]

Host: Sean Fuller, thanks for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast today.

Sean Fuller: Thanks, Gary. It’s great to be here.

Host: It’s been a while since we last saw each other.

Sean Fuller: It has been, I think it’s San Francisco or the steppes of Kazakhstan, places around the world.

Host: [Laughing] That’s right. Isn’t that weird that those are the two last places we can think about it? But it’s kind of cool. This is our first podcast that we’re recording back in the studio with a guest. So, this is, this is pretty special for me. It’s great to have you here. Wanted to talk about Gateway partnerships. This is awesome because what we’re going to be talking about here is a lot of your history in the International Space Station program, how that experience kind of paved the way to what you’re doing now. Want to start back here, though. Let’s start with your International Space Station experience because I think setting that context is going to really help us to tell this story. Tell me about some of your history with NASA.

Sean Fuller: Yeah. Well, I was actually very fortunate. I graduated in ’96 from Embry-Riddle [Aeronautical University]. And by the time I graduated, I knew where my first job was, and it brought me here to Houston. So, I’ve actually been here at JSC since the summer of ’96, so a lot of history in there. But I started out in the space station program as a mission planner, before we even launched. So, some of the early days of planning for space station and then quickly got involved in the Phase 1 Mir program, that was flying at that time. So, taking some of the lessons learned, I learned about this thing called Phase 1 that was getting us ready for Phase 2, which was the initial ISS. And so, taking those lessons learned out of that Phase 1 and bridging in into ISS. And so, really kind of got started very early on in my career here with that in, at the time MOD (Mission Operations Directorate), the operations directorate, working in those different areas. And then since then, just really been bridging the technical end and some of the programmatic pieces with international partners since those days.

Host: Yeah. So, tell me about that, when your, your time actually, getting to work with some other countries.

Sean Fuller: Yeah. So, when I started, like I said, I started in ’96, and I heard about this thing called Phase 1. And I got to talking to my boss and said, hey, I think we should be learning on this as we get ready for Phase 2. So, we had the life sciences organization, it was doing a lot of the NASA/Mir. And so, I kind of got involved with that early on there working with our Russian counterparts. We knew that that was going to be the first parts of ISS. They’d obviously had a long experience in space stations and working with crews. We’d had a lot of experience in the shuttle but this different timeframe, right, couple weeks’ worth versus months’ worth. So, I got involved with that. And I still remember my first trip to, to Moscow was in the summer of ’97. And standing in Red Square, kind of pinching myself, thinking, golly, you know, a year ago, year and a half ago, I was in school and never would have dreamt I’d be here, much less working on the space program, which I’d always wanted to do, and really kind of pulling those two things together. And so that really kind of set me off in it. You know, I was working, like I said, at that point helping the early planning for space station, developing those mission plans, but then working with our counterparts in Russia and really kind of learning from the two of them, to help integrate it into something that could be the best for all of us. So, I kind of got started in that, and I guess you could say that got bit by the bug, if you will, with it. And so I continued with that. And then as we got into the ISS program early on and setting up the Houston Support Group in Moscow and really kind of bringing together our teams as we worked together for the first mission. I was the, the lead for Expedition 1 for [Bill] Shep[herd] and Sergei [Krikalev] and Yuri [Gidzenko] —

Host: All right.

Sean Fuller: — early on there with ISS. And so, took it from that and then built on those experiences, came back from doing that first part, and jumped into working with our European and Japanese colleagues as they get ready to fly Columbus and the JEM (Japan Experiment Module) on ISS. And so, started building up those relationships and starting to formulate the operations interfaces, how we’re going to work together, and really kind of get those from the ground up. So, I had the benefit of starting at the infancy of ISS and kind of seeing that. It was well beyond the development phase, which is what I’m in now and learning a lot there, but in the early operations phase and building that up into ISS and really kind of branching out from there. So, it’s been a great experience. You know, when I now take a step and look back and say, I can see how all these dominoes kind of fit together, you know, at the time, you’re just having fun and really enjoying what you’re doing. Now you kind of see how the things fit together and lead to where you’re at today.

Host: Unbelievable. I mean, starting from the beginning, though, what’s, what’s cool about your experience is you’re talking about, you’re talking about the inception of what became one of the most recognizable, recognizable international partnerships that we have today. And you’ve seen that, right? So, you said you were there at the beginning and you’ve seen that progress into something. Tell me about that progression, from your time of making it all come together, from you said, the operational side of things, all these different countries working together, to building something that is a sustainable international partnership: everybody working together day by day to make International Space Station operations 20 years continuous.

Sean Fuller: Yeah. Absolutely. And so, if you look back at that, we kind of came and each had our own individual paths into space. And we’re figuring out how to work them together. So, if we go back to the early days of ISS, you almost had two parallel pieces. And how do we force those two things together and to work together? We each have our own ideas. And as I would tell people because something is different doesn’t make it wrong. And so, we’ve got to figure out how to get those to work together. Well, over the 20 years now of operation on ISS, it’s kind of like we can complete each other’s sentences at this point. You know, you really learn a lot working from each other, and you grow from each other. Each have different experiences that come in. You know, we look at it and on ISS we call it dissimilar redundancy: things that are done on the Russian segment that are different than how they’re done on the U.S. segment, but that saved our bacon more than once on each side because there is differences in there. And so, I tell you, just kind of early on, you’re figuring out how to take these pieces that are already done and get them to fit and work together. Now, if I fast forward into the Gateway world where we’re taking that partnership now to the next step, we’ve learned a lot of things and we could really, as we say, hit the ground running with Gateway. We have the established relationship with our partners. We know how to do the interfaces and interactions, whereas in ISS there’s a document, nine volumes, actually, that’s the interface between the programs, called the SPIP (Station Program Implementation Plan). We needed that because we hadn’t worked with each other before. So, we’d kind of put down a lot of processes and procedures and how we’re going to do things, formulating it and go and executing it. In Gateway, we just did our, our Gateway equivalent to it that’s one volume and about 80 pages, because we’ve got all this background behind us, and we, we are one integrated team now around the world. We came as separate teams and kind of had to figure out how to make that all work and work it together, and we’re very successful at that. Through that progression, the 20 years, starting with the crew and three crew and through the time when the shuttle was down and down to two crew, a lot of different ebbs and flows. Now to the six and more crew on ISS, we’ve progressed that partnership, our interactions and working together, how we’re complementing each other. You see a lot of it in the research that one does that benefits the other or joint research, really taking that into the Gateway, which is even more integrated. We have that tremendous foundation from ISS. And we can build upon that. And I think that’s really been some of the keys to Gateway in its, its early successes and the rapid pace because we do have that foundation of background amongst us. I’ll tell you, as I look across our partners for Gateway, there’s a lot of familiar faces from ISS that have transitioned now into the Gateway work.

Host: Well, that’s how you started, right? So last time I remember talking to you, this was, this was the San Francisco thing, this was when you were still part of the International Space Station program. Gateway was just spinning up. They were a program. They were getting built from the ground up. But what was nice is exactly that the narrative that you’re saying is, we have so much information to pull from, we have so many relationships to pull from, from International Space Station, you were helping them out from the space station side. So, what was that like on the space station side, starting that up and saying, hey, I can help you guys.

Sean Fuller: Yeah. Absolutely. And so, interestingly, I would say from an international partnership standpoint, the infancy of Gateway—and it wasn’t Gateway at the time—but the infancy of what are we going to do with the partnership, what’s our next expansion beyond low-Earth orbit and ISS, really began in about 2014. The partnership kind of came together. And at that point, we’ve had six crew or assembly complete, space station is doing great, we’re doing a lot of research, we’ve got the vehicles coming and going. And the partners are now looking, all of us, OK, what’s the next step for human exploration beyond ISS? And so, we, we kind of started as a partner looking at our national goals of each of us and how do we tie those together to goals into the future, and so, we started that early in 2014, 2015 timeframe, kind of starting that formulation at, what does that look like? You know, if we look at each different agency, there were goals on the lunar surface. There were goals to go to Mars, there were goals for asteroids. How do we stitch those things together with our capabilities? And so, we had something. It had many different names back in a time—Waypoint, Deep Space Gateway—that kind of said, hey, there’s probably a good synergy of a base, if you will, beyond low-Earth orbit, get away from, from the gravity of the Earth as a stepping point that can go to the lunar surface, if that’s what a goal is, or to go to Mars if that’s what the goal is. And so, we kind of started that in that early formulation. And so that’s kind of where I came in, after I was the director in Moscow for four years and came back and was asked, OK, take this partnership, and let’s kind of congeal those ideas, those goals, and step it forward whereas we had within NASA, as well, looking at what’s NASA’s next steps. And so, they’re kind of two separate things that had similar goals. And where I came in was kind of merging those together, both the NASA one and taking the international partner one. Now, I’ll tell you one of the things that I’ve learned. And so recently, we did the MOUs (Memorandum of Understanding) for Gateway, which are our agreements with the partners, formal agreements between, not NASA—a lot of people think it’s NASA, and while NASA executes it—it’s really the U.S. government and the governments with our partners. So, it’s a commitment of the government. But one of the things that we learned and a lot of thanks to our predecessors in ISS, is when they did those agreements in ISS in the ’97 timeframe, they foresaw that there may be an evolution of ISS. And so, actually, the ISS agreements said, hey, there’s a capability of the partners to evolve ISS to go beyond, we don’t know what that is, but to go beyond for this partnership. And so, when I came in, it was kind of taking all those pieces together, to stitch it into the international partnership that is Gateway today.

Host: Very cool. Now let’s build off of that. You talked about everybody had this idea, and it was even written into the agreements of early International Space Station that, hey, we can take this a step further and continue working together on whatever else is next. It just so happens to be Gateway. So, tell me about that. What is the Gateway? What did we come together and —

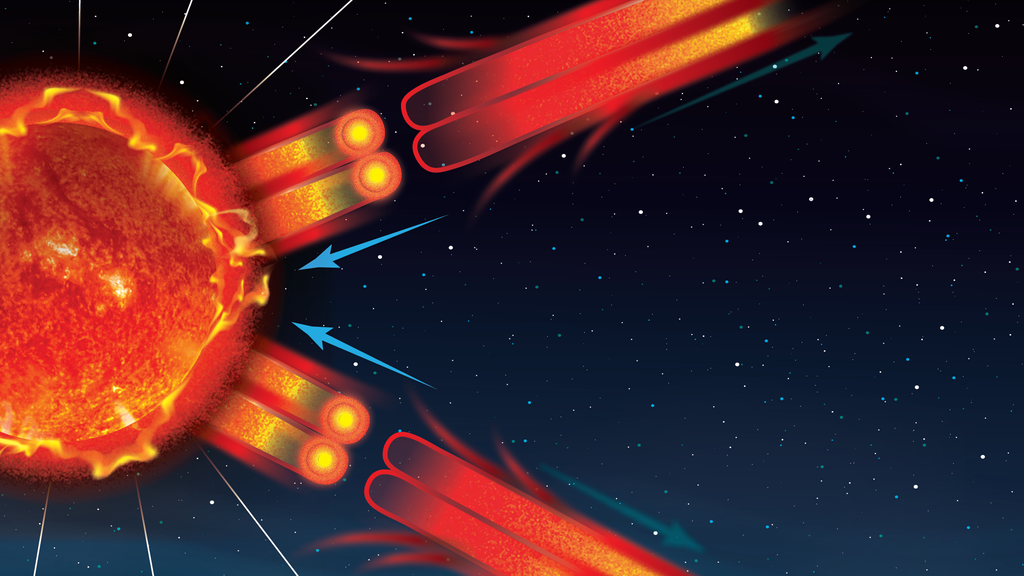

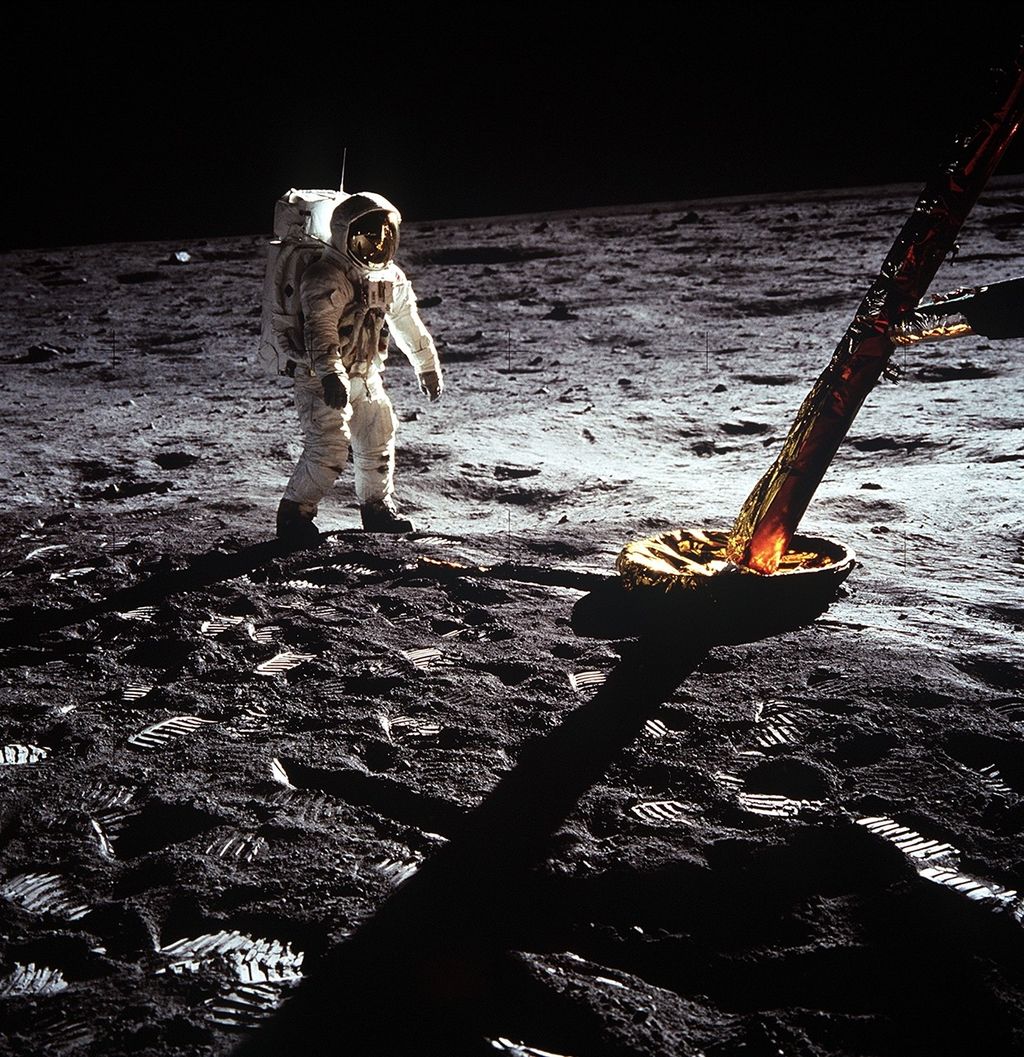

Sean Fuller: So, Gateway, that’s really, like I said, our stepping-stone is a location that helps support the aggregation and sustainability of going to the lunar surface. And so, if we look back in the Apollo era, right, we launched a Saturn V, and it was one rocket that carried the three crew out to lunar orbit and then two down to the surface for, Apollo 17 was three days. So, it’s three days on the surface. So, a lot of energy spent to do that and to go out and land on the surface, kind of do a couple days and then come back home. Gateway, or any outpost, but Gateway gives you a stepping-stone so we can bring the crew there, but we also have landers that can go there and stay there. And so, now the crew comes into this Gateway that’s orbiting around the Moon. They come in, they can operate, we can do research and in a completely different environment on Gateway, but then we put some of the crew into a lander as well to go down to the surface of, of the Moon. And in Gateway, in the Artemis program, they’ll be spending intervals of six days-ish on the surface of the Moon, given our orbits. A lot longer duration there. We don’t have to haul everything to the lunar surface and back every time. We have a staging point. We can fly logistics up in cargo vehicles that we’ll do to Gateway before the crew gets there. And so, we can really capitalize on all that, make it, as we call it, sustainable. And so, the, the ascent element of a lander can come back and stay at Gateway or stay in a lunar orbit and be reused in the future multiple times. And so that really helps us build a much more sustainable lunar exploration enterprise there for it. And then, as we look ahead, that’s a new environment, it’s outside of the Van Allen [Radiation] Belts so our radiation environment’s different. It can also be a stepping-stone to going off to places such as Mars as well: an aggregation point that we get out beyond Earth, put the pieces together, give them a test run and then go out to farther destinations. So, we talk about it as Gateway. And a lot of folks kind of equate it to, if we look at the U.S. and the Gateway city, St. Louis, and it was a stepping point going out to the West. It was the Gateway to the West. Well, our Gateway station is a Gateway for that exploration as well.

Host: And that’s really, it sounds like, Sean, this is the pitch. When you were going to the international partners and you’re saying, this is the next step. We all want, like — as these different nations, our next step is further exploration. This is it. We want you to come with us.

Sean Fuller: Absolutely. Each one of them wants to go beyond, right? We all have our ambitious goals.

Host: Yeah.

Sean Fuller: But one of the great things about partnerships, too, is, while you may have the strong desires, you know, like we say, if there’s not enough bucks, there’s not Buck Rogers. Well and here, we can take and pull the resources of everybody, we can all accomplish the goals, whereas doing it individually may not have the resources to do it. So, again, we take the partnership, a lot of strengths, all of us have learned a tremendous amount through ISS and through our ISS experiences. We can expand that now to this new environment. So, it is different than low-Earth orbit. It’s, it’s a next step. I wouldn’t say it’s a giant step up, but it’s a next step in that evolution there. So, we build upon a lot of our experiences, hardware operations in ISS, do those in the lunar orbit, and can now expand our capabilities. And, again, it allows that opportunities for all of us. If I look at the individual partners, you can surmise that perhaps not everyone would have the national capabilities, either resources or technically, to do those as an individual. So, when we work together, it really enables it for all of us. And it benefits all of us, too. NASA’s investment overall is a bit less. It lets us stretch that tax dollar further, just like our other countries can do as well.

Host: Very cool. So, what does that look like, then? If I’m going to Gateway, it’s an international outpost around the Moon. What are all the different components?

Sean Fuller: Yeah. Absolutely. It’s, so Gateway is a little different than ISS. We draw those comparisons a lot. But I will tell you, overall, it’s about a quarter the size, at the end, of ISS. The first couple of elements, we’re actually bending metal, as we say now, producing that hardware. There’s a Power and Propulsion Element that provides, just as its name says, power and propulsion for Gateway, although it has technical, technological enhancements there, too. We use a lot of chemical prop[ellant] on ISS to do our translation burns, to move the station or to control its attitude. The PPE (Power and Propulsion Element) for Gateway is going to use an electric thruster, advanced electric propulsion system for Gateway’s translation maneuvers. And so, this is a whole new, new realm, especially this size. Some smaller satellites, you use it on a much smaller scale, but we’re scaling it up. STMD (Space Technology Mission Directorate) and our colleagues are working with Aerojet, and so developing a larger engine that’s going to provide that capability for us. And so, you have a new technology in there, too; we can infuse this new technology for us. So that kind of builds the PPE. And then the next element is called HALO, Habitation and Logistics Outpost. That’s the first habitable volume, if you will, for Gateway. So, it’s, it’s a small volume. The modules are a bit smaller than they are on ISS, but it gives that initial capability as a place for the crew to initially come into. And so those two modules, actually, the PPE and the HALO, with some enhanced capabilities that we have now in launch vehicles, we’re building those and we’re going to integrate those on the ground and launch them as we call a co-manifested vehicle. So, one Falcon Heavy launch in November of 2024, we’ll launch those, and then they will spend, using this ion thruster, to spiral out, as we say, to the orbit. So, it’s going to take about ten months. They’ll launch it into an Earth orbit. But it uses electric propulsion to slowly spiral out to get to its orbit around the Moon in, about ten months later. And so that kind of creates our core piece of it. And I should say coupled with that, from the very beginning, we have our international partners along the way as well. Within there, there’s a comm[munication] system on HALO, a high-rate comm system, that will be used as a relay for items on the lunar surface, and so that our European colleagues are providing in there. Our Canadian colleagues are going to build an arm, I’ll talk about that in a few minutes, but arm and arm interface, so a location to put external payloads or utilities on. We’re going to fly that up. And, in fact, we’re going to fly it with some payloads, a NASA payload and an ESA (European Space Agency)-sponsored payload on that first vehicle. So, we’re going to start some utilization in realms that we haven’t seen before on that very first flight out. And our JAXA (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) colleagues are providing the, the energy storage or the battery system within HALO. So, we start as a partnership from the very beginning in, in Gateway when we launch the first piece of it in November of ’24. Now, after that, there’s a couple more elements that add up to make the assembly complete, Gateway, if you will. And so, after our initial flight, there’s a cadence of about every year after that of additional flights. And so, the next one will be what we refer to as the International Habitat, or the I-HAB. It’s a European-provided module with a lot of our JAXA colleagues, our Japanese colleagues with the systems inside of it, thermal control system, life support system that will really be the hub for life support and for the crew. It’s going to let us expand our mission durations—our early flights without I-HAB will rely on Orion life support systems. So, it has a limited timeframe. You can only fit so much in Orion. So, the I-HAB will have additional life support capabilities. That coupled with logistics will really let us expand our time in NRHO (near-rectilinear halo orbit), in the orbit around the Moon, or on the lunar surface. We look at 30-, 60-day missions now, given the resupply capabilities and the capabilities in I-HAB.

Host: Huh. So that’s really, yeah. This is, it sounds like this is a, it’s an international partnership, and part of the, part of the pitch on how everybody contribute is we can expand this. This is part of Artemis as a whole, as a sustainable program so building it from very short, the short duration missions, now adding this capability to the Gateway now, you can explore for longer. You can explore interesting parts of the Moon. It sounds like this is — Gateway is sort of the way to build Artemis to be that sustainable program.

Sean Fuller: Absolutely. I kind of call it the focal point where you kind of build off from there.

Host: Cool.

Sean Fuller: You know, you go off to the lunar surface. You expand from beyond there. But at the hub, you have Gateway where you can coalesce everything together to go off and do those additional missions out of there.

Host: Cool. So when you, you talked about the different ways that international partners are contributing; I wonder, I wonder how you tackled that because, right, when, the beginning of our talk, we talked about how you were starting to build these, these partnerships. I wonder, I wonder what that was like, traveling to the different respective agencies and saying, hey, we want you to contribute. And maybe, I don’t know if you said, here’s the way you can contribute or if they came to you with ideas. How did that all work?

Sean Fuller: Yeah. It was kind of a combination of the two.

Host: OK.

Sean Fuller: And so, if we look at each of our partners, you know, you look at, and our Canadian colleagues have a fantastic history of the robotic arm.

Host: Yeah.

Sean Fuller: The first arm on a shuttle; Canadarm2 on ISS. And so, they said, hey, we’ve got an expertise here. There’s a need for an external robotics on Gateway, and so we’d like to be the one that does that. And so that’s exactly what they’re doing. They have contracts now and are working to that. They’ll fly the arm with a logistics vehicle in 2026. It’s going to let us do things just like we do on ISS today, outside of Gateway without the need of a crew to take a spacewalk. Lot of consumables, time use in that; if we can do it from the ground with an arm, which is what we’ll do on Gateway, that’s great. And so, from a Canada standpoint, they kind of came in and say, hey, here’s what we want to do. Here’s how we can fit in it. This is our expertise. We can deliver this. Awesome. From our European colleagues, you know, somewhat of the similar. They’re looking to expand beyond the technology in Columbus and to really look at a module that’s more of a main core module, if you will, for Gateway, and the integration within that, too. And so, they had this, I described the I-HAB. But also, and I would say different in evolution is, is they are integrating our Japanese colleague’s contributions within there, so the life support system, the thermal control system. In the ISS, NASA is the integrator. In Gateway, NASA is the overall integrator. But with I-HAB, ESA is the integrator of that module. And so, they, they saw as an opportunity to stand up and provide that. Now, another module that ESA is providing called the, the ESPRIT (European System Providing Refueling Infrastructure and Telecommunications). It’s a refueling module. It provides refueling for the PPE, the Xenon propellant as well as the bipropellant for the chemical thrusters. That actually was one as we were putting together Gateway and looking at the different technical needs in there, there was a gap. We needed additional, some additional volume at the time and some refueling capability. And so that wasn’t one that a partner came in and said, this is what we want to bring to the table. But it was a need of the partnership, and our European colleagues stood up and said, hey, we’ve got some, some technologies in there. This is an area that we really want to expand upon. So, so we’ll kind of take this one and see what we can do and run with it. And so, it really is kind of a combination of all those that has made this, this possible.

Host: Very cool. And that’s really what it comes down to. You mentioned this before, Sean, which was, you know, why, why involve the international partners, right? And, but you said it was taking that tax dollars, taxpayer dollar as far as you can and bringing everyone else along for the ride. What are the overall goals, really, of not only NASA but what you’ve heard from working with our European colleagues, our Canadian colleagues, our JAXA colleagues? What have you heard their goals are that are all coming together, maybe their individual goals; and maybe there are shared goals across all of us?

Sean Fuller: Yeah. Exactly. This really is a conglomeration of all of that.

Host: Cool.

Sean Fuller: And so, each of them do have similar national goals. A lot of them, like we see, there’s a lot of interest on lunar surface. Lunar surface exploration, what does that mean? How can they contribute to it? Our JAXA colleagues, they’re working with their industry, looking at rovers. They have a strong desire for pressurized rovers and to provide that for lunar surface exploration. Well, Gateway is a method to get there. Similar, our European colleagues are looking at exploration and see that next step as the lunar surface. They have a lot of different ideas in terms of what that would be, how they could contribute to it. Of course, if you look at the lunar surface, it’s not necessarily one small station, if you will. There’s a lot of opportunities there. And so, I will tell you, I think each one of them is kind of looking in those realms on lunar surface activities. Those activities may be technological advancements for their industry. It may be scientific goals. It’s probably a combination of the two. But it’s where they can meet the national goals that they have within this international framework, as well. And then I would say each one of them, we also kind of look on the horizon, if you will, and say this is great, we want to kind of go expand to the, to the lunar, cislunar space, to the lunar surface, open up to industries, kind of see that expand there. And then where do we want to go beyond there? Well, that next horizon goal is Mars. And so, each of us kind of has our own similar national goals, I think, that take us out there. But we see how it can fit within the framework. Working together, again, each of us can help enable our national goals as well. And so, we’re, actually, early on in the Gateway development, we had at a time listed out each of the national goals and kind of drew circles of how they all stitched together, and how this supports all of it, to achieve that.

Host: Very cool. All right. So, you threw out a couple of dates earlier in the podcast, and I wanted to, to kind of gauge where we are now and what we have left to do to get to some of those dates. So, let’s start with where we are now in terms of middle of 2021.

Sean Fuller: OK. Well, we’re making a lot of progress right now. And each one, because it’s an assembly sequence, is a little different. So, we talked about some of those. The PPE, built by Maxar, it’s actually a derivative of a satellite bus that they have already. And so, there’s changes to support the Gateway. Certainly, it’s more power, more control than they typically have on a satellite bus. So, there’s enhancements in there. But it’s kind of a well-understood design with these enhancements. And so, they kind of have that wrapped up into their overall commercial development. With the HALO, that, that’s a pressurized module. Northrop Grumman’s our contractor for it. The primary structure for the HALO, they’re using an outfit in Italy called TASI, Thales Alenia Space Italy; happens to be also the entity that builds the Cygnus pressurized modules for ISS, and has a lot of experience of other pressurized modules on ISS. They are building those elements today. There’s several of the pressurized sections that have been completed in Turin, Italy. They’ll get into molding them together and then shipping them to Northrop Grumman for the final outfitting and integrating. So, in that aspect, that has hardware being built. If I move on to the next module, the I-HAB, actually last week I was in Europe for the preliminary design review of that module, of the I-HAB. And so, we were going through the detailed design, the requirements, the flow-down, making sure that the module, the design of it, the preliminary design, was completing the objectives with the right engineering margins on there, and completing it within the scope of an integrated Gateway. Because it’s not its own standalone module; it pulls power, for example, from, from the Gateway power bus. And so, are we maintaining it within those margins? It’s going to be delivered via SLS (Space Launch System) and Orion on what we call a co-manifested payload. So, it’ll launch on top of an SLS rocket. Orion, after they get into orbit, will turn around and attach to I-HAB and then tug it out to Gateway, to plug it into Gateway, if you will. So, looking at is the mass, the launch mass, how does that compare to the capabilities of the SLS rocket? So, going through that design phase of it. They will begin some of the very early manufacturing of I-HAB the fall of this year at the same place, actually, in Turin, Italy, with TASI. So, we have some commonality that, as it turns out, has been through there with TASI. Now, some of the later elements, the refueling module, it’s in the early requirement phase. And so, later this year, we’ll have a systems requirement review, or an SRR, where we’ll take a look at the requirements that will feed into the preliminary design of that module, make, again, making sure that the flow-down of requirements from the Gateway level into that module and that implementation is a flow-through. So, each one of those are kind of at different stages along. We have some that it’s hardware being built and soon to be tested. We have software in development and actually being tested on different early levels so that software being tested here at JSC. And so, as we take these many pieces to integrate them into the Gateway, each one is kind of at different stages. But it’s always great when we can look and see the hardware now and you actually, physically see it come together. There’s a lot of graphics of what it will look like, but now, as you see the hardware in Italy and then also at Palo Alto [California] and with Maxar, as they’re developing that, some of the early testing of solar arrays, very similar to solar arrays that we’re about to upgrade on ISS. And so, we see that hardware coming together.

Host: Yeah. Well, I actually should, should mention that, we’re talking about these international partners to, to build this, this outpost around the Moon, we should mention commercial is a part of it, too. And is that, how is that a little bit different from how we’ve done things in the past?

Sean Fuller: Yeah. Absolutely. So, we talk about we have different partners in Gateway.

Host: Yeah.

Sean Fuller: Some are international, some are commercial partners.

Host: Right.

Sean Fuller: And so, we have the commercial partners, the Maxar and Northrop Grumman with HALO. What makes it a little different is their corporate investment, if you will, in these modules. So, they have objectives that they want to complete as well, that helps them in their corporate world. I mention Maxar and the bus; the PPE is built off of their bus. So, developments in there, particularly developments in the propulsion area, that has applications later for them in the commercial industry. And so, we talk about partners, it means that it’s not always fully NASA money invested in there. They put some skin in the game as well, because they get the return that they then use in their commercial industry afterwards. And so that, too, is it’s a little bit different. And so, what that means from us in a design is there’s opportunities for influence and change, if you will, coming from our commercial partners. So, we have the NASA requirements that really meet the international requirements of what does it take to build Gateway, because all of our Gateway requirements are agreed by NASA and our partners. You know, this isn’t just a NASA Gateway, it really is the international partner Gateway, so it’s our agreements and requirements across. But then our commercial partners, they have avenues to invest opportunities within there that support their goals that may be outside of Gateway, but it complements it, and can help them as well. And so that’s really where we see our commercial partnership come in for Gateway. And we’ll have some that we’ve learned on ISS. ISS, our cargo resupply on the NASA side is commercial now. We contract commercially for those deliveries. That’s exactly the model that we’re using for Gateway. We awarded to SpaceX last year for the first Gateway logistics resupply contract. So, we won’t own the module, right; we’re contracting for the delivery of hardware to Gateway. So, a very similar thing is happening there as we call a commercial partner with SpaceX for that cargo delivery.

Host: Yeah. Seems to be a pretty common model nowadays. It seems to be something that, that really works.

Sean Fuller: Yeah. And I think, and I think that’s where you see the progression of the industry.

Host: Yeah.

Sean Fuller: And so, there’s the demand out there that sparks that. That’s why we see the multiple ones on ISS, more in the future perhaps. We see the commercial market, and they can sustain that. And so, we can contract for the delivery of the cargo. The design of the module, the — risks that they take in there, that’s kind of on their side.

Host: So, you mentioned the first couple of phases of Gateway. Sounds like the PPE, HALO, those first couple of things. Falcon Heavy takes it into lunar orbit, you said. Then the Orion and the SLS is going to take that I-HAB. What are the phases here? Is that, is that Phase 1, and then is there scalable opportunity, opportunities from there to get to what you were talking about a little bit earlier, those 30-day, you know, Moon missions?

Sean Fuller: Yeah. So, so we kind of talk about it in terms of initial capability —

Host: initial.

Sean Fuller: — and sustained capability.

Host: Got it.

Sean Fuller: So initial capability is that co-manifested vehicle. It’s the PPE and the HALO that gives you that initial waypoint, if you will, that Orion can go to, and a lander could go to as well. But it doesn’t have the life support systems in there. So, they can support the crew there, there’s fans to mix the air, but there’s not scrubbing of the air or the full ECLSS (environmental control and life support system) system for the crew there. When we add the I-HAB, we add that into it. And so, we call the, actually the overall sustained capability, when you want to have this station, if you will, there’s key capabilities you want it to have: that life support capability; the arm, the robotic arm externally that can support a crew outside or without a crew to do your external maintenance or your utilization on it, so the external arm; the refueling capability, which also adds windows in there, so that’s our, our viewing port, if you will, give us some fantastic views of the Moon —

Host: That’ll be cool. [laughing].

Sean Fuller: — from Gateway. Absolutely. And then we’ll also add an airlock, so a crew airlock on there to Gateway. And so that really rounds out what we call the sustained capability of Gateway.

Host: OK.

Sean Fuller: And so, if we look at that timeframe to all those pieces, it’s about the 2028 timeframe that all of that will be complete.

Host: Got it. So, what excites you most, then, coming up? I mean, that’s, that’s a lot coming up in not too much time —

Sean Fuller: Absolutely.

Host: — to, to build, so, we’re talking about a lunar outpost, and we’re talking about building a sustainable presence for regular Moon missions, human presence on the Moon. That’s what you’re hoping to do. That’s got to be pretty exciting.

Sean Fuller: Yeah, it’s pretty wild. You know, when I think about it and one of the things that I like to do, and I have daughters 16 and 14 years old, and we like to go out and see space station fly over, right?

Host: Yeah.

Sean Fuller: We can look at that and see it in the sky. And anyone that’s 20 or younger now, their entire life somebody has lived on the space station; you can see it. And so, to me, I kind of step back and realize, there’s going to be a day, maybe we’re going to need a telescope, but we’ll see the same thing of a human outpost around the Moon. And it’s not that far off. We’re talking about the four years from now timeframe where we will have that out there, and that will show where humanity has now gone, and we’ve stretched the envelope to there. We’ve gone there before and come back, kind of a little teaser, if you will, to go out and kind of looked in the frontier and say, hey, we can do this. Now let’s come back and do it with the wagons and make it sustainable. That’s where we’re going. And so I think and when you have, we’ll have Artemis II the first time that we have a crew go out around the Moon in Orion, but we go on and put the crew going to Gateway, that’s really marking a next step in our permanent expansion of that human exploration capability. So, I look at that, and sometimes you kind of look back and say, wow, that’s really only a handful of years away. That’s pretty amazing, and it also scares you. That’s only a handful years away! Let’s get to work.

Host: You’ve got a lot to do [laughing].

Sean Fuller: Yeah.

Host: That is awesome. Sean, we talked a lot about the partnerships to build exactly this, this outpost in lunar orbit, and this exciting time that’s right at our doorstep. It’s coming up real soon. Did I miss anything before I go ahead and let you go?

Sean Fuller: I just, Gary, I appreciate it. I think, you know, this really is taking us to that next step. And we see it. I’m always enthused, and you see the partnership. The other thing that impresses me is the world sees us in the exploration. I’m amazed when I travel around the world and go through the airport and see the people wearing T-shirts with the NASA meatball on it, the stores that are selling lunar rovers or, or astronauts in suits walking on the lunar surface. So, it’s really exciting to see that, and it’s awesome to be a part of it. We’ve got a great team here and around the agency really pulling us together, and really around the world that makes that happen. And getting that, that recognition and everybody around the world to come together to do it, you really feel like, hey, this is something that we’re kind of locking arms in, and we’re going to make this happen and really bring humanity to that next step. And it’s going to be a great thing. And, you know, doing that, gosh, and then we’ll have it as a leaping pad to the next thing. A lot of exciting times in front of us.

Host: Yeah. We’re all standing by very eagerly to see what you and the international community do to, to make this thing a reality. Sean Fuller, thanks for coming on the podcast today.

Sean Fuller: Thank you, Gary. Appreciate it.

[ Music]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. I certainly learned a lot from Sean Fuller today all about the Gateway. I hope you did too. If you want to learn more, we’ve got a website for you, NASA.gov/gateway. We’re one of many NASA podcasts across the agency. We’re going to be talking about Gateway a lot on this program, and Artemis as well. And a lot of the other podcasts are going to be doing the same thing. So, go to NASA.gov/podcasts. Check them all out. You can find us there and follow us. We’re also on social media. We’re on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Use the hashtag #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea for the show, and just make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston We Have a Podcast. This episode was recorded on June 15, 2021. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Pat Ryan, Norah Moran, Belinda Pulido, Jennifer Hernandez, Rachel Kraft, Isidro Reyna and Christina Zaid. And, of course, thanks to Sean Fuller for taking the time to come on the show. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.