This article is from the 2019 NESC Technical Update.

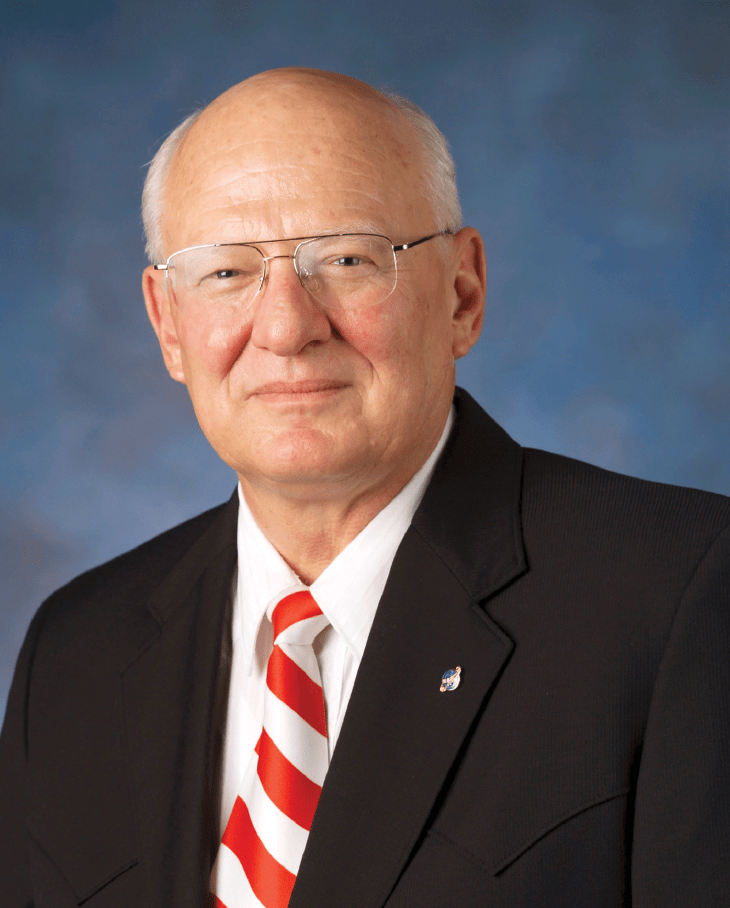

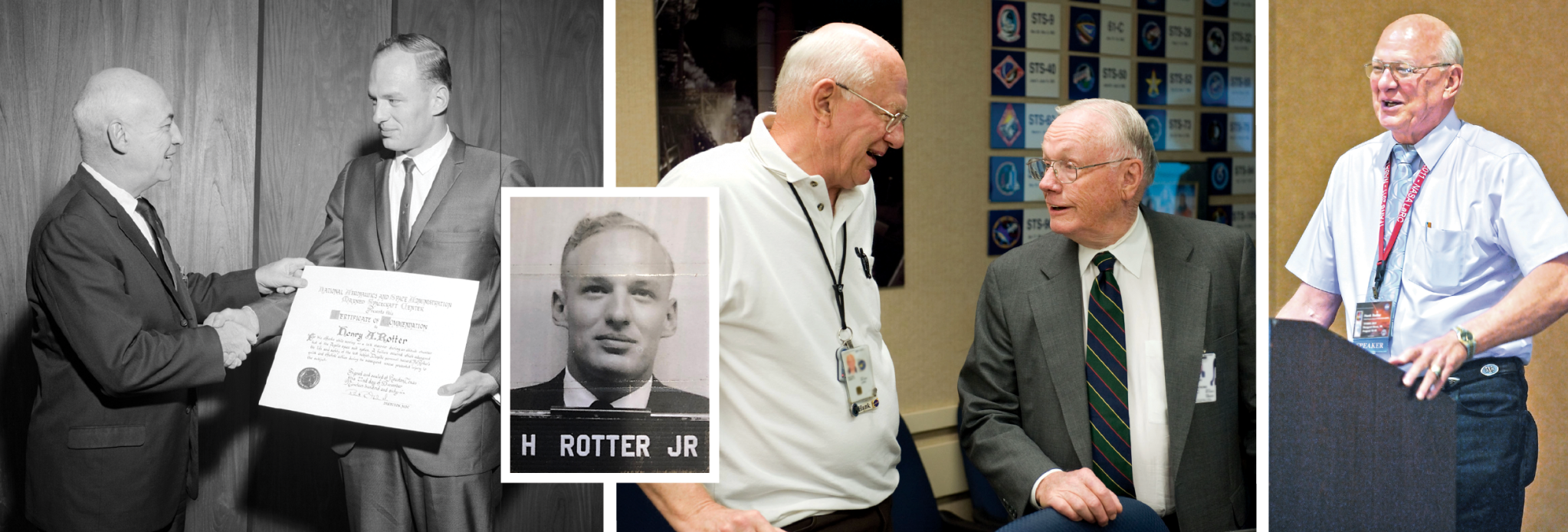

After 56 years, Mr. Henry (Hank) Rotter, Jr., retired from NASA in late 2019. From the first Moon landing to the development of Orion, his career not only spanned the NASA space program but also contributed to its success. His departure came just as the Agency began to implement plans to return to the Moon in 2024. But before leaving, Mr. Rotter shared a few highlights and lessons learned for his successors, knowing firsthand the challenges that lay before them.

Of all the important things required to send humans safely into space and bring them home again, ego is not one of them. “You need to understand you’re not always the smartest guy in the room,” said Mr. Hank Rotter. It was a leadership lesson he learned early in his career when he discovered a technician he was working with did not feel comfortable sharing what may have been a better idea for the test they were about to perform. Or when a design mistake could have been avoided simply by talking to someone skilled in brazing. “We’re trained across many technical discipline fields, but we’re not experts in all of them,” he said.

After four decades at NASA, however, Mr. Rotter became the NASA Technical Fellow for Environmental Control & Life Support (ECLS) leading assessments for the NESC on the Space Shuttle, the International Space Station (ISS), and the Orion Program, and assisting the U.S. and British Navies with emergency oxygen supply issues on submarines due to similarity in supplies used on the ISS. The NESC brought him on board in 2003 because of his critical problem solving-skills and vast experience with ECLS systems, which by that time was 40 years deep, its roots going back to the Apollo Program.

Fresh out of college in 1963, the Texas native took a job with NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center, now JSC, ensuring the human centrifuge was ready to train astronauts, testing crew seat designs on the drop tower to limit landing impact loads, and using vacuum chambers to test spacesuit designs to ensure they were tough enough to withstand the harsh conditions of lunar extravehicular activities (EVA). As the mechanical engineer for the centrifuge, Mr. Rotter “crawled all over that thing, which was 20 feet off the ground. And they didn’t have safety belts in those days,” he said. Mr. Rotter was a test subject as well, taking the centrifuge for a ride before the astronauts began their training. “I took an 11g ride for a few seconds where I weighed a ton and a 4g ride for 4 minutes,” he said. “You have to use stomach muscles to breathe because can’t use your chest. After that ride, I had to drink some Pepsi just to get enough energy to pick up my sandwich.”

It was during centrifuge training that he met astronaut Ed White. “The Apollo 1 fire was very emotional for me. He was the first astronaut to introduce himself to me, and he lost his life in that fire. He was my first hero,” said Mr. Rotter, who would take part in every Apollo mission that followed.

While he reveled in the success of Apollo 11, the Apollo 13 mission put all of his technical and problem-solving skills to the test. Walking into the Mission Evaluation Room that day in April 1970, he “knew something bad had happened.” He would work the next 18 hours to figure out the best way to transfer water to the lunar excursion module (LEM) for the astronauts. “We laid out all the tubing and connectors on the table that were available in the command module and the LEM,” he said. “We solved the problem of using square lithium hydroxide cans in the LEM, which had round slots.” The experience involved some of the first in-flight maintenance performed for the program. “Afterward, the in-flight maintenance book was the biggest book on board,” he said. “We learned more about those two spacecraft in that mission than we’d known before.”

The oxygen supply umbilical that Mr. Rotter designed allowed crews of the Apollo 15 and subsequent missions to perform EVAs that would take them 20 feet away from the command module hatch to retrieve film cartridges from the mapping cameras. He also wrote the accompanying procedures on how to handle potential malfunctions and emergencies.

What Apollo taught him transferred well to the Shuttle Program, where he worked for 20 years on ECLS systems, payload integration, and the orbiter tunnel adapter used by crew to access Spacelab, Spacehab, Mir, ISS, and to perform EVAs. On STS-109, a blockage in the coolant system for the orbiter avionics, which were critical for reentry, threatened to bring an early end to the mission. Mr. Rotter and others worked all night to devise a way to protect the system and ensure, even in the worst-case scenario, that the system would get the crew home safely. On board that last successful flight for Columbia was Mission Specialist and Flight Engineer, Dr. Nancy Currie, with whom Mr. Rotter would eventually work on NESC assessments.

After the 2003 Columbia accident, Mr. Rotter came to work for the NESC. “Solving problems in my days as a subsystem manager and having to find rationale and corrective actions to fly again fit right in with what the NESC was doing.”

During his 16-year NESC tenure, he helped the Space Shuttle Program in its return to flight, led teams on investigations into satellite and Mars Science Laboratory issues, and solved challenges for ISS that ranged from addressing heat exchanger and water recovery system anomalies to identifying the cause of water leaking into an astronaut’s helmet during an EVA. “I told them a week after it happened where the problem was, but it took a year to prove me right,” he said of the formal investigation’s conclusion.

With a half century of NASA work behind him, Mr. Rotter has a lot to reminisce about, but he decided there is not much he would change about his career path. “I might have given my family a little more time,” he said. “I’ve told many young engineers that it is hard to balance yourself, your family, and your work. You have to think about all three.” He also wishes he would have spoken up on a few things sooner than he did. After the Apollo 1 fire, he found himself in California, reviewing plans for the rebuild of the service module for Apollo 7. He was asked by a manager to present his take. “I was young, nervous, and I’m in front of 100 people saying this is what I think they need to do. The manager actually wanted to hear what I had to say.” That boosted his confidence, he said. “The more confidence I got, the more I spoke up.”

On September 3rd he officially said goodbye to NASA. “JSC was my extended family. We worked hard and played hard together, and it wasn’t unusual to see us running down the hall or running between buildings because we didn’t have cell phones then. We were dedicated,” he said.

Mr. Rotter left behind a new generation of engineers working on the Artemis Program, which will take astronauts back to the Moon and on to Mars, but he leaves knowing his work at NASA helped chart their course. “I still look up at the Moon every once and a while and think, I helped men to get there.”