After more than three months living and working aboard the International Space Station (ISS), the Expedition 1 crew of NASA astronaut William P. Shepherd, Yuri P. Gidzenko, and Sergei K. Krikalev of Roscosmos received their second group of visitors. The STS-98 crew of Kenneth D. Cockrell, Mark L. Polansky, Robert L. Curbeam, Marsha S. Ivins, and Thomas D. Jones arrived aboard space shuttle Atlantis to deliver the U.S. Laboratory module Destiny to the ISS. During three spacewalks, the astronauts attached the module to the front of the station, greatly expanding its habitable volume. The joint crews began activating the new element, preparing it for the arrival of future systems and research facilities on subsequent space shuttle missions. The delivery of Destiny marked a milestone in the establishment of a world-class research facility in low-Earth orbit.

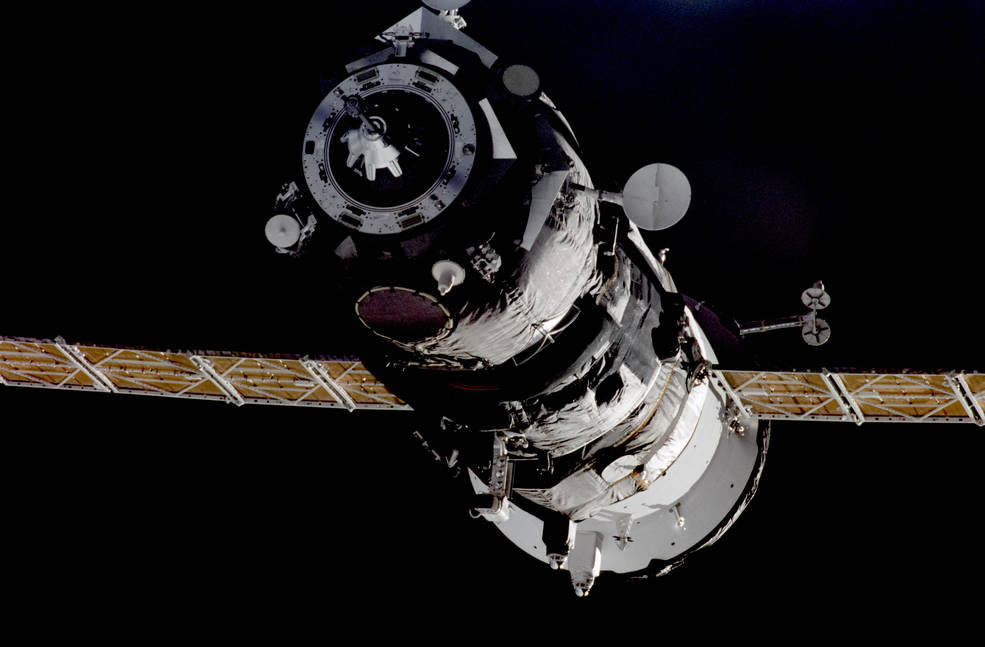

Left: Progress M1-4, also known as 2P in the International Space Station (ISS) assembly sequence, approaches the ISS just before docking. Middle: Expedition 1 astronaut William M. Shepherd works with the Middeck Active Control Experiment-II (MACE-II) in the Node 1 module. Right: Shepherd building the temporary wardroom table in the Zvezda Service Module.

Shepherd, Gidzenko, and Krikalev continued to improve the habitability of their orbital outpost. They deployed the Interim Resistive Exercise Device (IRED), delivered during the STS-97 mission in December 2000, in the Node 1 module. The IRED provided a third exercise device for the onboard crew with Shepherd declaring on Dec. 12, 2000, “The weight room is open” on the ISS. The Progress M1-4 cargo vehicle that undocked just prior to STS-97 and had been station keeping nearby, re-docked with the ISS on Dec. 26. Using leftover stowage frames from the cargo craft, Shepherd, Gideznko, and Krikalev designed and built a temporary wardroom table since the permanent one was not due to arrive for several months. The table gave them a place to enjoy their meals together. The crew members set up the Chibis Lower Body Negative Device to monitor and challenge their cardiovascular systems, in the Zvezda Service Module. Shepherd, Gidzenko, and Krikalev were the first expedition team to spend Christmas and New Year’s aboard the ISS. For Christmas, they sent a holiday message to the ground that began, “As the most ‘forward deployed’ citizens of the planet at this moment, We, the first expedition crew aboard Space Station Alpha, send our holiday greetings to Earth.” For New Year’s Day, Shepherd honored a naval tradition by writing a poem as the first entry in the onboard logbook for 2001. In January 2001, Shepherd conducted the Middeck Active Control Experiment-II, the first active American research experiment aboard the ISS. On Feb. 2, the crew participated in an event to open the Payload Operations and Integration Center (POIC) at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. The POIC became the nerve center of research operations aboard the ISS. On Feb. 7, the crew celebrated its 100th day in space, and the next day undocked the Progress M1-4 cargo craft for the second and final time.

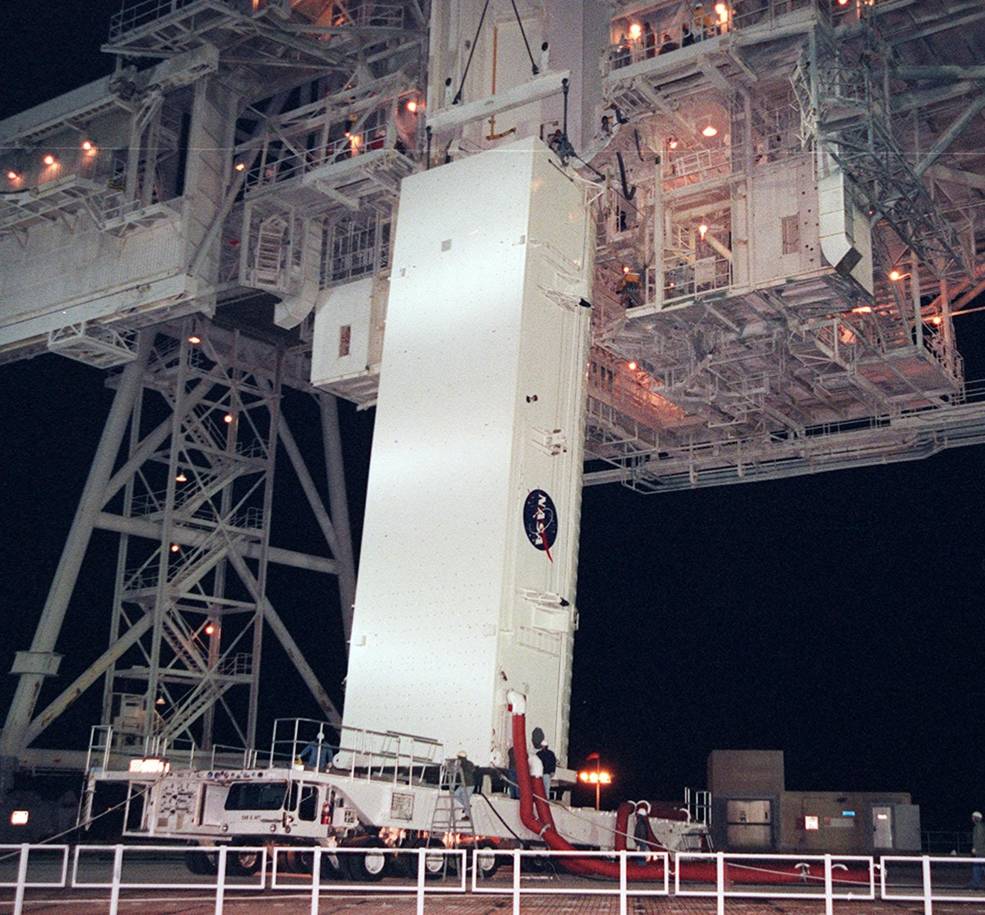

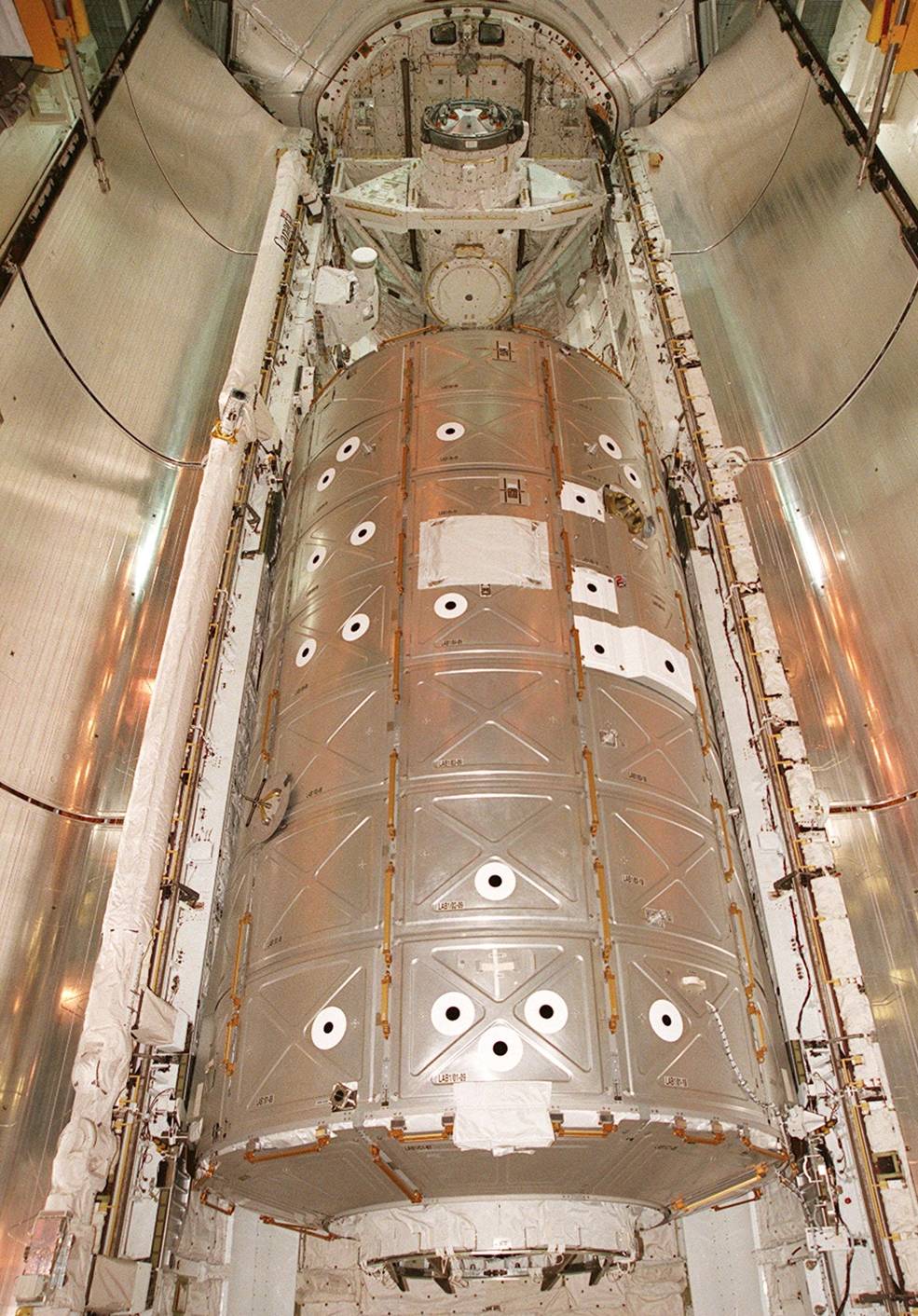

Left: At NASA’s Kennedy Space Center’s (KSC) Space Station Processing Facility, KSC Director Roy D. Bridges, left, Randy H. Brinkley, International Space Station Program Manager, and Kenneth D. Cockrell, commander of STS-98, at the Nov. 30, 1998 Destiny naming ceremony. Middle: The payload canister containing the Destiny module arriving at Launch Pad 39A at KSC. Right: The Destiny module installed in the payload bay of space shuttle Atlantis.

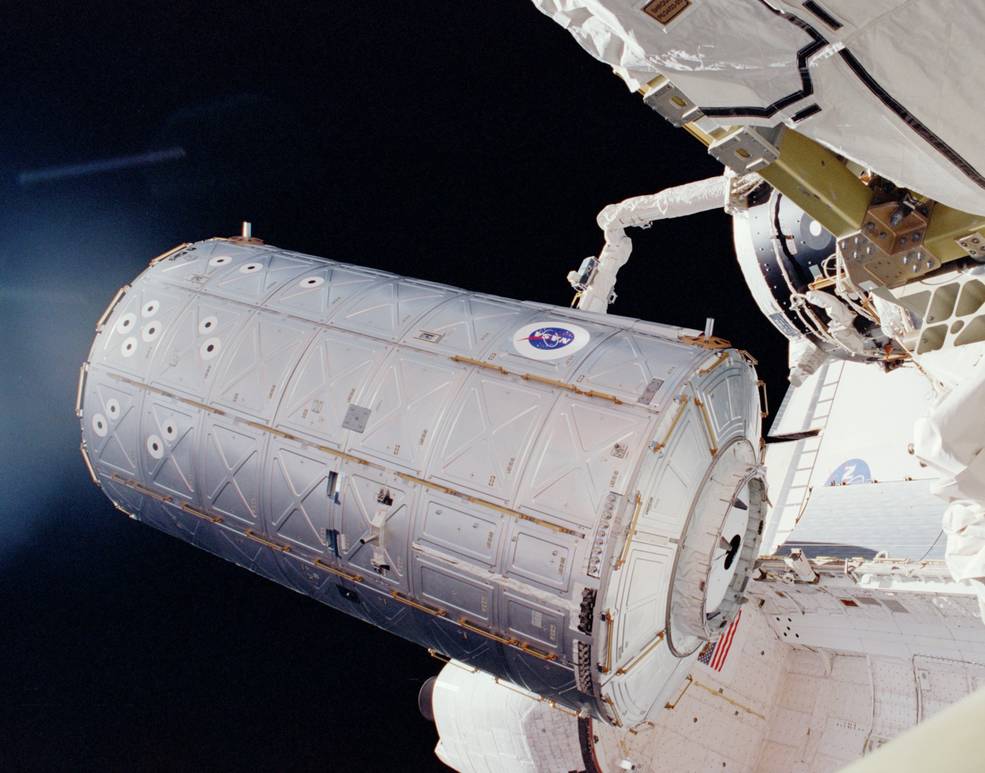

The primary objective of the STS-98 mission was to deliver the U.S. Laboratory module to the ISS. Construction of the 28-foot-long research module began in 1995, and after it arrived at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC), it formally received the name Destiny during a ceremony on Nov. 30, 1998. Destiny became the centerpiece of NASA’s research activities at the orbiting facility while also providing essential core systems functions. Designed to house 10 systems and 13 research racks, each weighing about 1,200 pounds, Destiny launched with only five systems racks due to upmass constraints on the space shuttle. Those five racks provided critical functions to the station, such as electrical power distribution, cooling, air revitalization, and temperature and humidity control. The remaining racks arrived on subsequent space shuttle flights. Destiny also included a nadir-facing optical quality window for Earth observations.

Left: The STS-98 crew patch. Right: STS-98 astronauts Robert L. Curbeam, left, Mark L. Polansky, Marsha S. Ivins, Kenneth D. Cockrell, and Thomas D. Jones.

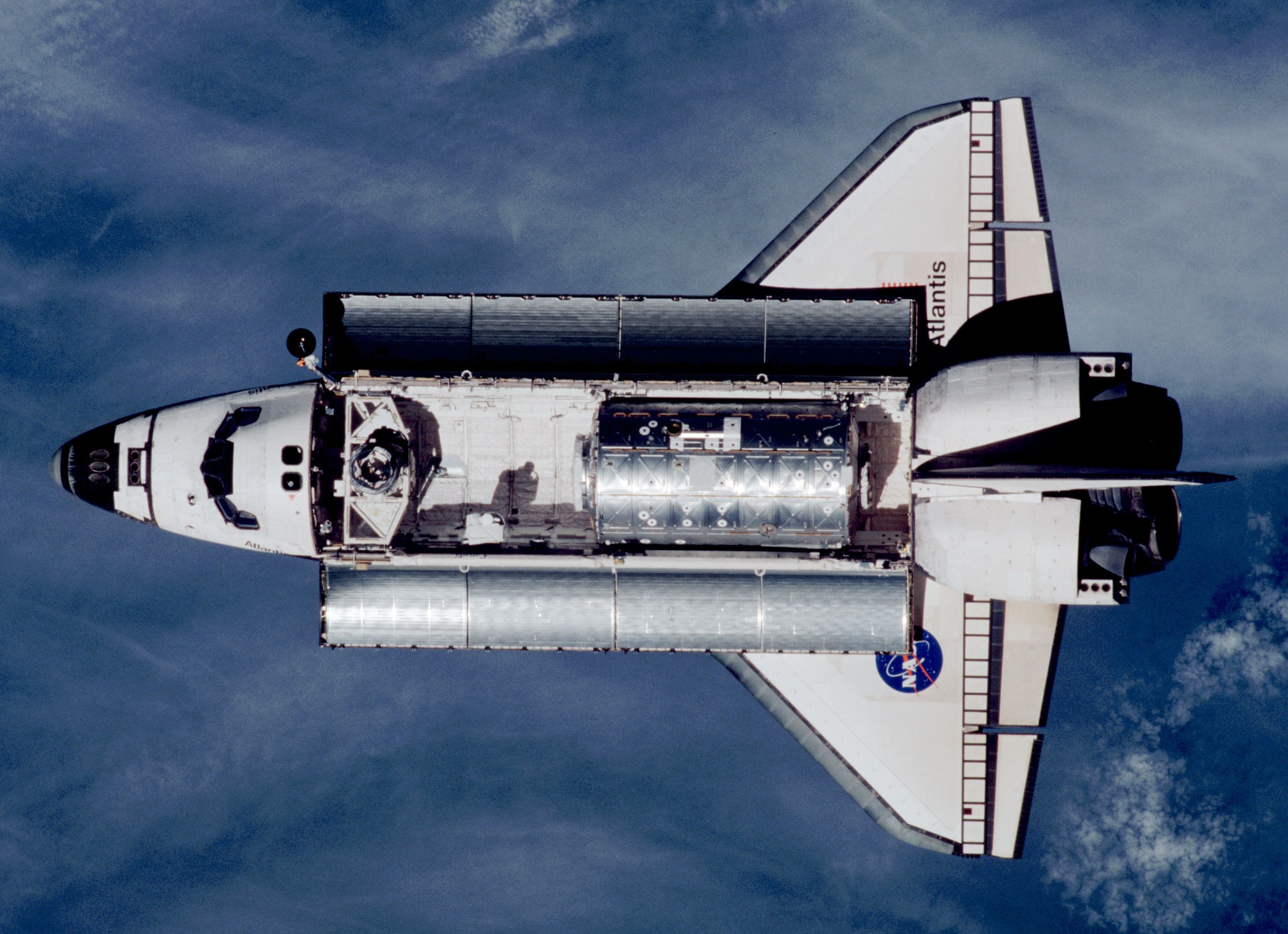

The seventh space shuttle assembly and resupply mission to the orbital facility began a few minutes after sunset on Feb. 7, 2001, with the launch of space shuttle Atlantis from KSC’s Launch Pad 39A on the STS-98 mission. Less than two days later, Cockrell guided Atlantis to a smooth docking with the ISS at the Pressurized Mating Adapter-3, or PMA-3, located on the nadir or Earth-facing port of the Node 1 module, also known as Unity. The Expedition 1 crew observed the docking, the third visit by Atlantis to the ISS. The astronauts opened the hatches between Atlantis and the ISS for about four hours for some early transfers and then closed them to allow the spacewalks of the next few days to proceed.

Left: Launch of Atlantis on space shuttle mission STS-98. Middle: View of the International Space Station (ISS) from Atlantis during the rendezvous and docking maneuver. Right: View from inside the ISS of space shuttle Atlantis with the Destiny laboratory module visible in the payload bay.

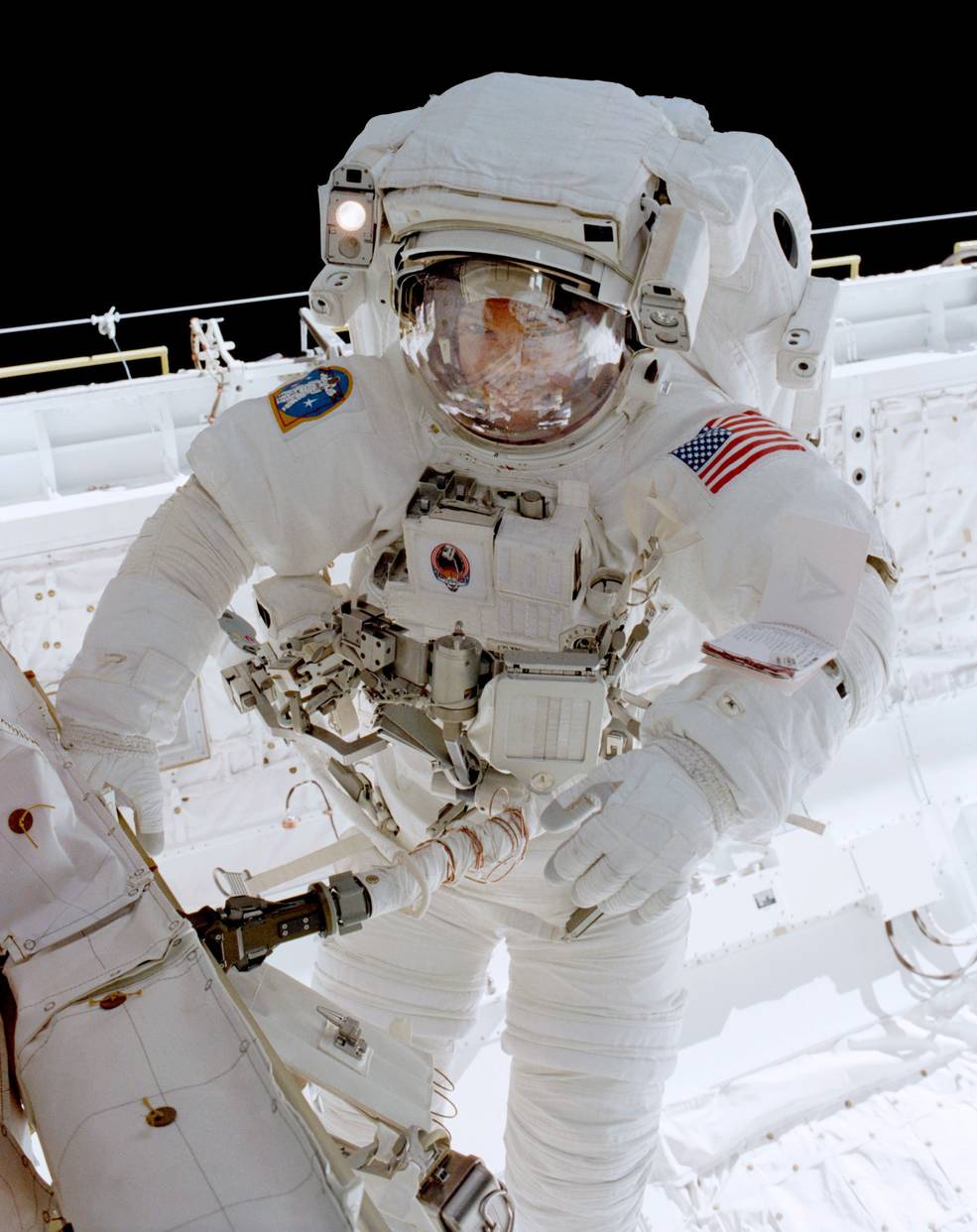

Left: The joint crews of STS-98 and Expedition 1 pose in the Unity Node 1 module. Middle: The shuttle’s remote manipulator lists the U.S. laboratory module Destiny for transfer to the International Space Station. Right: NASA astronaut Robert L. Curbeam during the first STS-98 spacewalk.

On Feb. 10, the mission’s fourth day, using the shuttle’s robotic arm, Ivins grappled the PMA-2 on the forward port of the Unity module and removed it to begin its transfer to a temporary location on the Z1 truss, this clearing the port for Destiny. Meanwhile, Jones and Curbeam exited the shuttle’s airlock to begin the first spacewalk. First working in separate locations, Curbeam disconnected cables between Atlantis and Destiny while Jones translated up to the Z1 truss to assist Ivins with relocating and securing the PMA-2 in that location. Ivins then grappled Destiny, lifted it out of the payload bay, rotated it 180 degrees, and steered it to attach it to Unity’s forward port. Bolts in the berthing mechanism ensured a tight link between the two modules. The mission’s first spacewalk lasted 7 hours 33 minutes. The arrival of Destiny added 32,000 pounds to the overall mass of the ISS and increased its habitable volume by 41%. After its installation, Cockrell and Shepherd began to remotely activate Destiny’s systems. The next morning, the Expedition 1 and STS-98 crews entered Destiny for the first time to continue its activation.

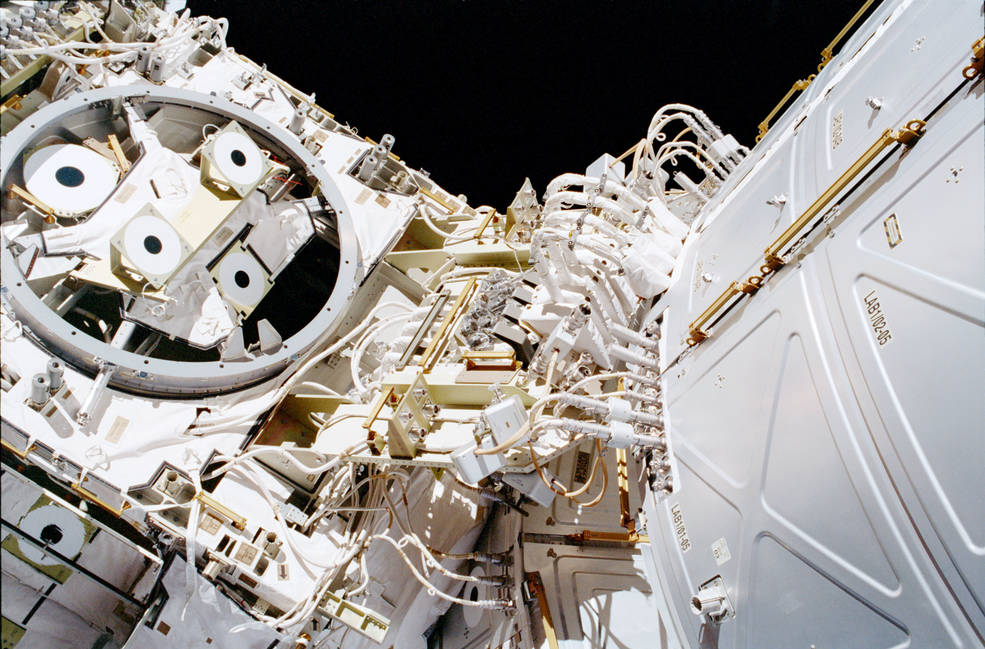

Left: The interior of the Destiny laboratory module after hatch opening. Right: An image taken during the second STS-98 spacewalk showing the complex connection between Destiny at right and the Z1 truss.

Left: NASA astronaut Robert L. Curbeam during the second STS-98 spacewalk. Middle: STS-98 astronauts Kenneth D. Cockrell, left, Thomas D. Jones, Mark L. Polansky, and Curbeam prepare for the third spacewalk. Right: Jones during the third spacewalk of the mission.

On Feb. 12, Jones and Curbeam ventured outside for their second spacewalk. Their first major task involved assisting Ivins with removing the PMA-2 from its temporary location and attaching it to the forward hatch of Destiny to allow future shuttles to dock there. During the remainder of the 6-hour 50-minute spacewalk, they completed numerous other tasks to prepare Destiny for its long orbital stay. Jones and Curbeam ventured out a third time on Feb. 14 to complete the remaining installation tasks during a spacewalk lasting 5 hours 25 minutes. The two crews spent the next two days completing transfers between Atlantis and the ISS and readying Destiny for its operations.

Left: The STS-98 and Expedition 1 crews pose inside the newly activated Destiny module. Right: The STS-98 crew poses for a photo on the flight deck of Atlantis.

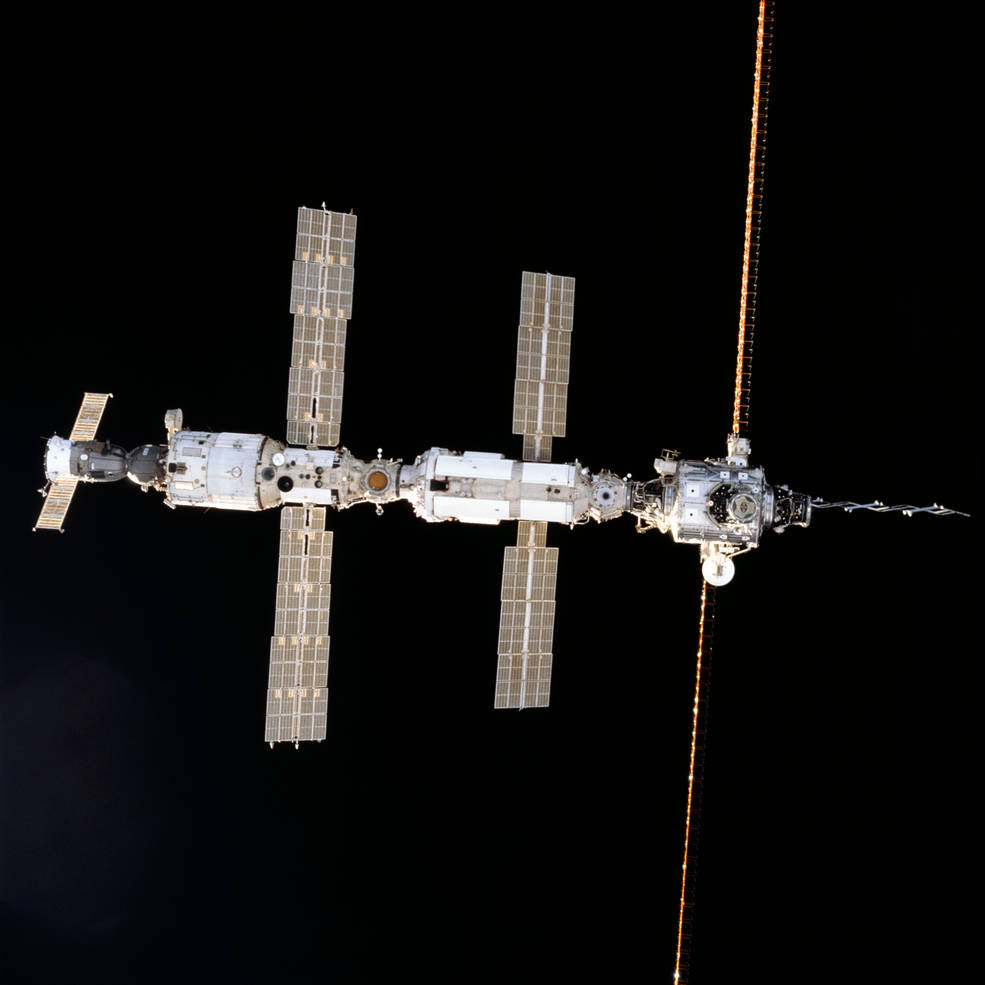

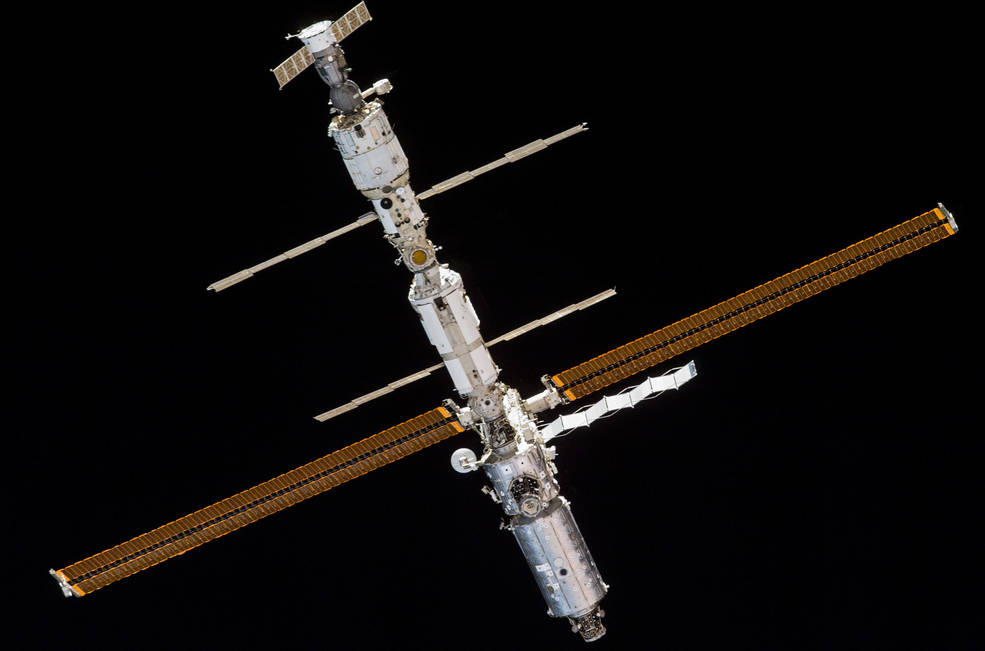

With Polansky at the controls, Atlantis undocked from the ISS on Feb. 16 and completed a fly-around of the expanded station, with the crew taking photographs to document its condition. Inclement weather at KSC forced the crew to stay in orbit an extra two days and diverted the landing to Edwards Air Force Base in California. On Feb. 20, the astronauts closed Atlantis’ payload bay doors, put on their launch and entry suits, strapped into their seats, and fired the shuttle’s engines for the trip back to Earth. Cockrell guided Atlantis to a smooth landing, ending a highly successful 13-day mission, adding the Destiny module to enable a robust research program aboard the ISS.

Left: A view of the International Space Station as seen from Atlantis during its departure, with the newly added Destiny module at lower right. Right: Atlantis makes a smooth landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California.

Enjoy the crew-narrated video about the STS-98 mission.